Growing up, my dad has this big rusty vise on his work bench and we’d use it for all kinds of stuff ranging from holding mower blades and axes during sharpening to bending metal for brackets and so forth. I knew it came from my grandfather’s farm in New Hampshire but not much else., When my parents moved near us, my dad brought the vise with him and installed it on a tool bench in their new garage.

Life can be harsh. I have a lot of good memories about my parents but nothing really prepares you for when they pass away. I was close to my dad and to this day, when I use one of his old tools, it makes me feel good – kind of like he’s still here and happy to see me using something of his – hopefully the right way.

At any rate, when we had to sell their house and clean stuff out, I snagged the big old vise and stuck it on the floor in the corner of my shop and really didn’t think much about it for almost five years. One day I started thinking about installing a second vise in my shop near another area where I do a lot of work that requires both work holding and a vise that can withstand 50-100 ft/lbs of torque. I figured I had two options – I have a 6″ Harbor Freight unit somewhere buried in my shop that I could dig out or I could go find my dad’s and take a closer look at it.

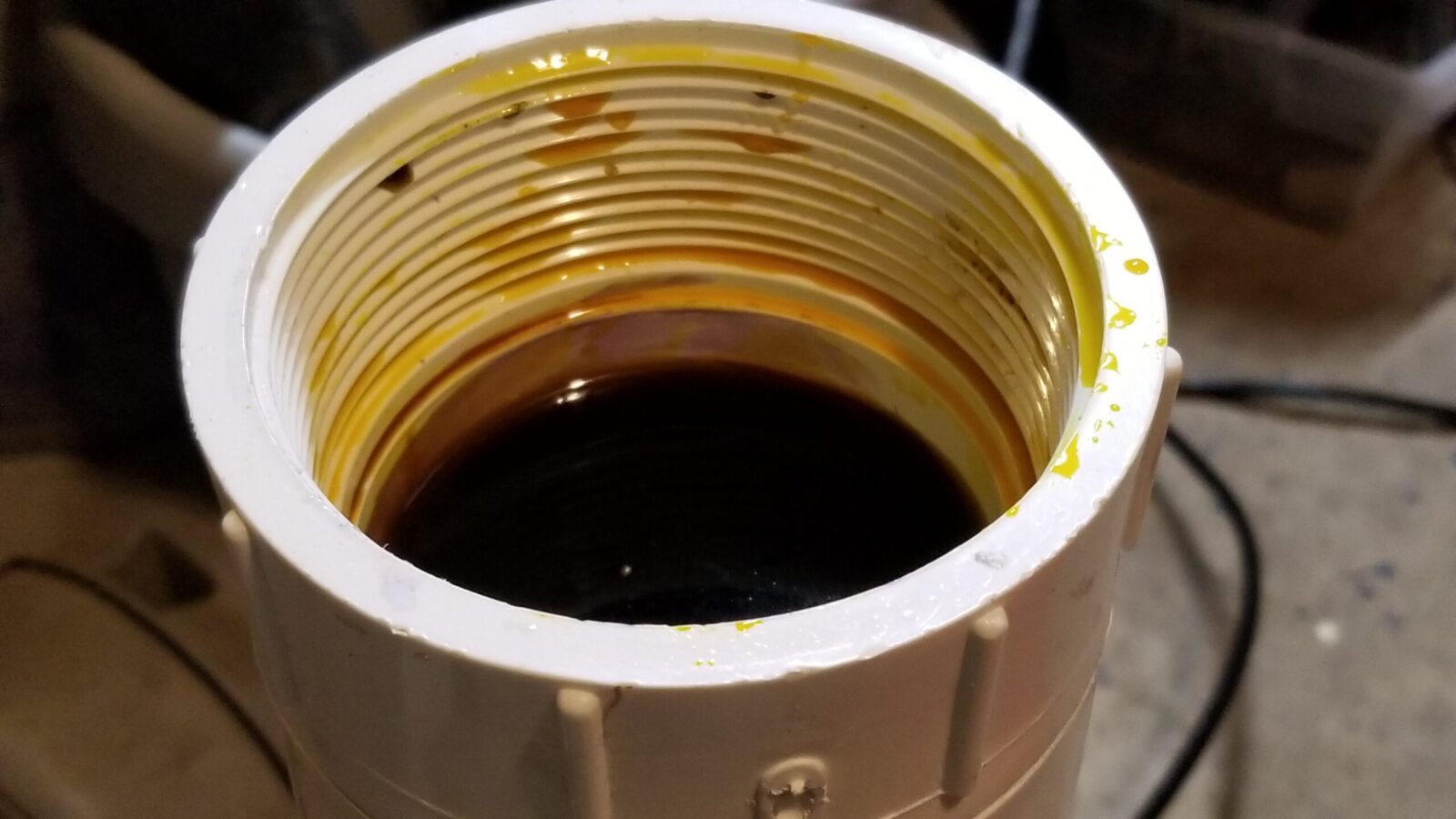

So. I dug out the old vise from under a work bench and blew off a ton of dust and dirt. The first thing that I noticed was that it weighed a ton and the second was that it was remarkably beefy and actually in really good shape other than surface rust. The action moved fairly well albeit a little gritty. Everything felt fairly tight meaning nothing seemed to be bent or broken. Last but not least, other than missing the handle on the locking nut, everything seemed to be there.

Where did Samson vises come from?

I did some searching on the web and found mention that Samson vises were sold by Sears from about 1908 to 1939 based on searching for “Samson Machinists” on ancestry.com. This page is from a 1923 Sears catalog and was copied from Vintagemachinery.org:

There it is down in the lower-left – 99N5263. A 3-1/2″ jaw width with a 5″ opening, weight was 37 pounds and cost a whopping $9.30!! Wow! Now, when my grandpa actually bought it, I have no idea. If my dad knew, he never said or I don’t recall – at this point, I’m really not sure.

By the way, in the catalog ad above, look at the weight of the 5266 5″ vise – 93 pounds! That would be a fun one to find. It must be enormous – I’ll have to keep my eye out for one 🙂

By the way, I couldn’t find a definitive answer about who made the Samson vises for Sears. Some people thought it was Reed but I haven’t confirmed that. If you search on Reed Vises, you will see some similar designs but I did not see an exact match. I emailed both Reed and Yost to see if they can share any insights. If I find out, I’ll update this post.

| 8/25/2020 Update: I got a very nice email from James about Samson vises based on some research he did: “Samson Vises were the Sears house brand before Craftsman took over in 1927. Samson Vises were made by Rock Island Vise Company for Sears and Roebuck out of Rock Island, Illinois.” |

Restoring the old vise for regular use

Other than quite a bit of surface rust, it was really in very shape and I decided to use the old vise. The next thing I had to decide was what to do with the finish – it was rusty my whole life so I thought about just oiling the rust and sealing it. Another part wanted to fix it up. I honestly thought about it for a few days because I couldn’t do anything right away. In the end, I decided to refinish it. From what I could tell the vises were originally black and either partially or fully painted. My vise had zero paint on it anywhere.

| Note: I am not doing a 100% overhaul to make it look like when it shipped from Sears. I wanted to clean it up some have it be functional. I just want to be clear in case any purists take issue with my use of the term “restoration”. |

So, the first step was to disassemble the vise both to make sure it was indeed salvageable and also to clean everything. The weather wasn’t cooperating so you’ll some photos were taken indoors and some outdoors so bear with me.

Conclusion

So the vise is back in use. Every time I use it, I feel good about it and hope my dad approves.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.