As the Russo-Ukrainian War approaches the culmination of its fourth year in late 2025, the strategic landscape is defined by a profound divergence in the trajectories of the two belligerents. The user’s intuition that the differences between the current state of the Ukrainian and Russian war machines would be “marked” is not only correct but underscores the fundamental nature of the conflict’s evolution. While the Russian Federation has largely settled into a strategy of industrial regression—relying on the mass reactivation of Soviet legacy armor, the simplification of technological inputs to bypass sanctions, and a brute-force mobilization of manpower—Ukraine has entered a period of strategic inflection characterized by rapid technological integration, industrial localization, and the institutionalization of asymmetric warfare.1

The analysis of late 2025 reveals that Ukraine is no longer merely surviving through the absorption of foreign aid; it is actively constructing a sovereign “deterrence ecosystem.” This ecosystem is built upon three pillars: the operationalization of an indigenous long-range strike complex capable of disregarding Western political caveats; the creation of the world’s first independent branch of service dedicated to unmanned systems; and the integration of its domestic defense industrial base (DIB) with Western manufacturing giants to form a localized production capability.4

This divergence is driven by necessity. Lacking the strategic depth of Russia’s Soviet-era stockpiles—where T-62 tanks are now being refurbished with crude field modifications and “cope cages” to fill losses—Ukraine has been forced to substitute mass with precision and software-defined lethality.7 The result is a Ukrainian force structure that is paradoxically heterogeneous—struggling with a “zoo” of incompatible NATO platforms—yet simultaneously pioneering network-centric capabilities like the “Delta” system that are now being sought by NATO members themselves.9 This report provides an exhaustive examination of these dynamics, contrasting the “regression and mass” strategy of Russia with the “evolution and integration” strategy of Ukraine, and detailing the specific industrial, logistical, and operational realities of late 2025.

2. The Indigenous Long-Range Strike Complex: Breaking the Range Limit

For the first two years of the full-scale invasion, Ukraine’s ability to project power was severely constrained by the geopolitical caveats attached to Western security assistance. Systems such as the HIMARS GMLRS and the Storm Shadow/SCALP-EG cruise missiles came with strict “geofencing” restrictions, prohibiting strikes on sovereign Russian territory to manage escalation risks. By late 2025, Kyiv has successfully shattered these constraints, not through diplomatic negotiation, but through the maturation of its own industrial capabilities. The emergence of a multi-layered, indigenous strike complex has fundamentally altered the strategic calculus, allowing Ukraine to threaten Russian logistics, airfields, and industrial hubs deep behind the border without seeking external permission.3

2.1 The Resurrection of “Sapsan” (Hrim-2)

The most consequential development in Ukraine’s strategic arsenal is the operational deployment of the Sapsan (also known as Hrim-2 or Grim-2) operational-tactical missile system. Originally conceived in 2006 as a superior successor to the aging Soviet Tochka-U, the program suffered from chronic underfunding and bureaucratic inertia for over a decade. However, the existential imperatives of 2022 forced an accelerated research and development cycle, transforming prototypes into combat-ready systems by late 2025.11

In December 2025, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy publicly confirmed that the Sapsan had begun combat operations, ending months of speculation regarding unexplained high-velocity strikes on Russian military infrastructure.11 The Sapsan represents a functional analogue to the Russian Iskander-M, but with critical distinctions tailored to Ukraine’s needs. The system is a single-stage solid-propellant ballistic missile with a confirmed operational range of approximately 500 kilometers for the domestic version, significantly outranging the export-limited 280-kilometer variants previously marketed to foreign partners.11

The strategic impact of the Sapsan cannot be overstated. With a warhead payload estimated at 480 kilograms and a terminal velocity reaching Mach 5.2, the missile presents a severe challenge to Russian air defense networks.12 Standard Russian interceptors, such as the S-300 and S-400 systems, struggle against the high-angle, high-speed terminal trajectory of the Sapsan, particularly when the launch originates from unexpected vectors. Unlike the subsonic cruise missiles and drones that have characterized previous Ukrainian deep strikes, the Sapsan’s ballistic profile reduces the reaction time for Russian defenders to mere minutes. This capability forces the Russian Aerospace Forces (VKS) to displace their staging airfields further into the interior, thereby reducing sortie rates and increasing the wear on airframes that are already suffering from sanctions-related maintenance deficits.11

2.2 The “Missile-Drone” Hybrid Ecosystem

While the Sapsan provides a high-end ballistic capability, Ukraine has simultaneously pioneered a new category of “missile-drones” designed to bridge the gap between expensive cruise missiles and slow, propeller-driven loitering munitions. This approach reflects a philosophy of “asymmetric cost imposition”—forcing Russia to expend scarce and expensive air defense interceptors against relatively low-cost, high-volume threats.14

The Palyanytsia, described as a “rocket-drone,” epitomizes this design philosophy. Utilizing a jet engine, the Palyanytsia achieves speeds significantly higher than the Iranian-designed Shahed drones used by Russia, yet it remains far cheaper to produce than a standard cruise missile like the Neptune or Storm Shadow.4 This system occupies the “middle tier” of Ukraine’s strike complex, designed to saturate air defenses and strike time-sensitive targets that would otherwise escape slower drones.

Complementing the Palyanytsia is the Peklo (meaning “Hell”), another entrant in this hybrid class designed for mass production. These systems, along with the Flamingo heavy cruise missile, create a diverse threat profile that complicates the air picture for Russian radar operators.4 By presenting a mix of ballistic trajectories (Sapsan), supersonic cruise profiles (Long Neptune), and high-speed drone swarms (Palyanytsia/Peklo), Ukraine creates a “kill web” that overwhelms the integrated air defense systems (IADS) of the adversary.

2.3 The Evolution of the Neptune

The R-360 Neptune, initially famous for the sinking of the cruiser Moskva in 2022, has undergone a significant evolution. By late 2025, the system has been adapted from a coastal defense anti-ship missile into a dedicated land-attack cruise missile, referred to as the “Long Neptune”.4 This variant features extended fuel capacity and updated guidance systems, including terrain-following radar and GPS/INS navigation, allowing it to strike targets deep within the Russian interior. Official reports indicate that the range of the Neptune has been increased to approximately 1,000 kilometers, placing Moscow and other critical command centers well within its engagement envelope.4

The table below summarizes the capabilities of Ukraine’s indigenous strike complex as of late 2025, highlighting the layered nature of this new deterrence capability.

| System Name | Type | Operational Range | Role | Status (Late 2025) |

| Sapsan (Hrim-2) | Ballistic Missile | ~500 km | Deep Precision Strike, Bunker Busting | Combat Active 11 |

| Long Neptune | Cruise Missile | ~1,000 km | Strategic Infrastructure Strike | Serial Production 4 |

| Palyanytsia | Jet-Powered Drone | ~700 km (Est.) | Air Defense Saturation, Time-Sensitive Targets | Combat Active 14 |

| Vilkha-M | Guided MLRS | ~130-150 km | Tactical/Operational Precision Strike | Resumed Production 15 |

| Peklo | Missile-Drone | Unspecified | High-Volume Saturation | In Service 4 |

3. The Industrial Base Revolution: From Donation to Localization

If the defining characteristic of 2022-2023 was the solicitation of emergency aid from Western partners, the period of 2024-2025 is defined by the “localization” of defense production. Recognizing that Western stockpiles are finite and that political will in donor nations is subject to electoral volatility, Ukraine has aggressively courted Western defense giants to establish production facilities directly on Ukrainian soil. This strategy aims to shorten logistics chains, reduce dependency on foreign aid packages, and integrate Ukraine into the European NATO industrial base even prior to formal membership.6

3.1 The Rheinmetall Case Study: Building Under Fire

The experience of Rheinmetall AG, Germany’s largest arms manufacturer, serves as a bellwether for this industrial transition. By late 2025, Rheinmetall’s commitment to Ukraine has evolved from the supply of vehicles to deep industrial integration. The company has established a joint venture, in which it holds a 51% stake, to produce 155mm artillery ammunition—the absolute lifeblood of the attrition war in the Donbas.6

However, the reality of constructing high-tech manufacturing facilities in an active war zone has proven to be fraught with friction. The construction of the ammunition plant was delayed into late 2025, a setback attributed to a decision by the Ukrainian government to change the facility’s location.18 This decision was almost certainly driven by intelligence regarding potential Russian missile strikes, necessitating a move to a more hardened or geographically shielded site to ensure the facility’s survivability. Despite these delays, Rheinmetall CEO Armin Papperger has confirmed that once the location is finalized, the modular nature of the plant will allow for construction to be completed within 12 months, mirroring the speed of their domestic German facilities.20

Beyond ammunition, Rheinmetall is moving to produce the Lynx KF41 infantry fighting vehicle (IFV) in Ukraine. The Lynx represents a generational leap over the Soviet BMP-1 and BMP-2 series currently in service, offering modular armor, advanced optics, and superior crew protection. The production of the first five vehicles began in Germany for immediate delivery, with the ultimate goal of transferring the technology for full local manufacturing.20 This shift from “repairing” to “manufacturing” marks a critical maturity point in the Ukrainian DIB.

3.2 The Baykar “Iron Bird” Factory

Turkish drone manufacturer Baykar has proceeded with the construction of its factory near Kyiv, with completion slated for August 2025.22 Unlike Western companies that have largely focused on maintenance and ammunition initially, Baykar is building a full-cycle production facility for the Bayraktar TB2 and TB3 drones.23

This facility is highly symbolic and strategic. It has been targeted by Russian missiles at least four times during its construction phase, yet work has continued—a testament to the resilience of the project and the strategic commitment of the Turkish partner.24 The factory will employ Ukrainian-made engines for the drones, creating a closed-loop production cycle that benefits both the Turkish airframe designers and the Ukrainian propulsion industry.25 This collaboration underscores a deepening strategic axis between Kyiv and Ankara, independent of broader NATO dynamics.

3.3 BAE Systems and the Artillery Coalition

BAE Systems has established a local legal entity in Ukraine to facilitate the maintenance and eventual production of the L119 105mm Light Gun.16 The L119 has proven highly effective in the muddy, contested terrain of Eastern Ukraine due to its mobility and rate of fire. By localizing the maintenance of these systems, Ukraine drastically reduces the “turnaround time”—the critical metric of how long a gun is out of the fight for repairs. Agreements signed in late 2025 aim to transition from repair to the manufacturing of spare parts and eventually gun barrels, restoring a critical manufacturing capability that is scarce even in Western Europe.16

3.4 Domestic Production Surge

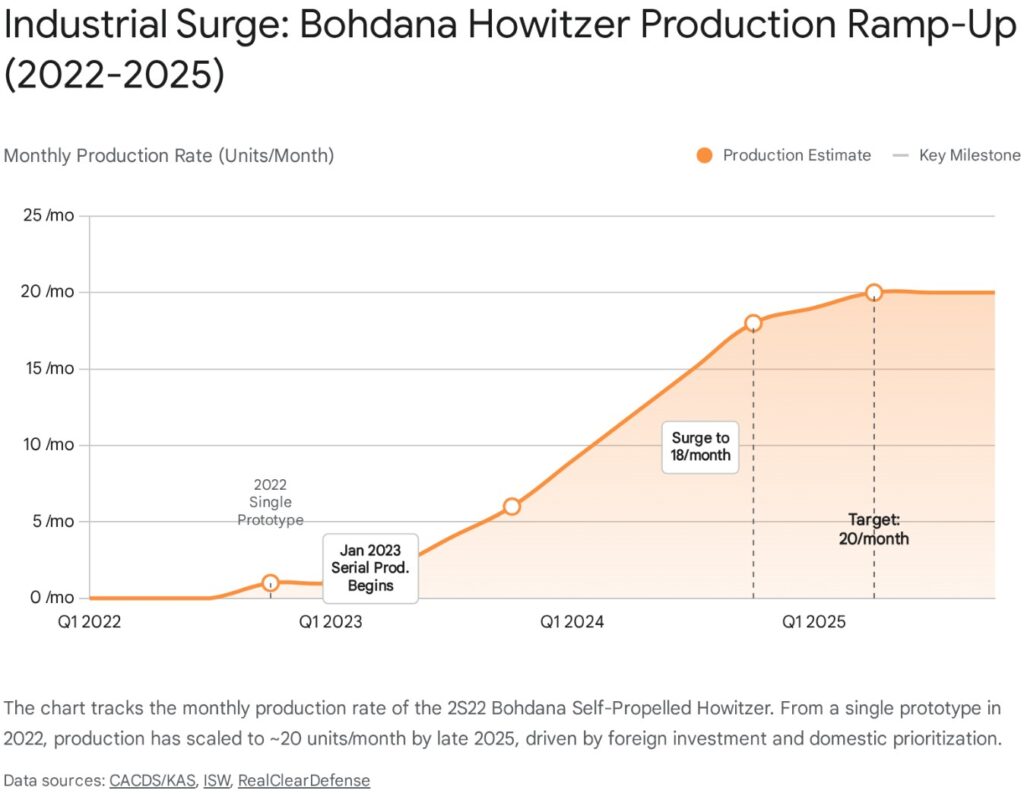

Parallel to these joint ventures, Ukraine’s domestic production has surged. The production of the 2S22 Bohdana self-propelled howitzer, a NATO-standard 155mm system mounted on a truck chassis, has reached a rate of 18-20 units per month by late 2025.4 This annualizes to over 200 new artillery systems per year—a figure that exceeds the total pre-war artillery procurement of many major NATO powers. Additionally, private companies like “Ukrainian Armored Vehicles” have scaled the production of mortars to 1,200 units annually and mines to 240,000 units, indicating that the domestic DIB is successfully filling the gaps left by fluctuating foreign aid.4

4. The Unmanned Systems Forces: Institutionalizing the Drone War

In a structural innovation that predates similar initiatives in Russia and most Western armies, Ukraine established the Unmanned Systems Forces (USF) as a separate, independent branch of its Armed Forces in 2024, achieving full operational capability by late 2025.5 This move signals a doctrinal shift, elevating drone warfare from a support function—akin to signals or logistics—to a primary combat arm comparable to the infantry or artillery.

4.1 Doctrine, Standardization, and the “Drone Line”

The primary mandate of the USF is to impose order on the chaos of the “drone zoo.” For years, Ukrainian units relied on a patchwork of volunteer-supplied commercial drones, resulting in thousands of incompatible platforms. The USF has implemented the “Drone Line” project, which centralizes the procurement and standardization of drones across the force.30 This initiative aims to streamline supply chains, ensuring that batteries, controllers, and spare parts are interchangeable across different units, a critical logistical requirement for sustaining high-intensity operations.

Furthermore, the USF has centralized pilot training. Moving away from the ad-hoc, unit-level training that characterized the early war, the USF has established standardized training centers that disseminate the latest tactical lessons—such as evading new Russian electronic warfare (EW) frequencies or executing terminal guidance maneuvers against moving targets—across the entire military.31 This institutional memory is a key asymmetric advantage over Russia, where drone competencies remain largely compartmentalized within specific units or dependent on individual commanders’ initiative.32

4.2 Scaling the “Missile-Drone”

The USF is also the primary operator of the new class of “missile-drones” discussed previously. By placing these strategic assets under a dedicated command, Ukraine ensures that they are employed in coordinated operational campaigns rather than penny-packet tactical strikes. The ability to coordinate a swarm of Palyanytsia jet-drones to suppress air defenses, followed immediately by Sapsan ballistic strikes on the exposed targets, represents a level of combined-arms synchronization that is only possible through a unified command structure like the USF.30

5. Network-Centric Warfare: The “Delta” Advantage

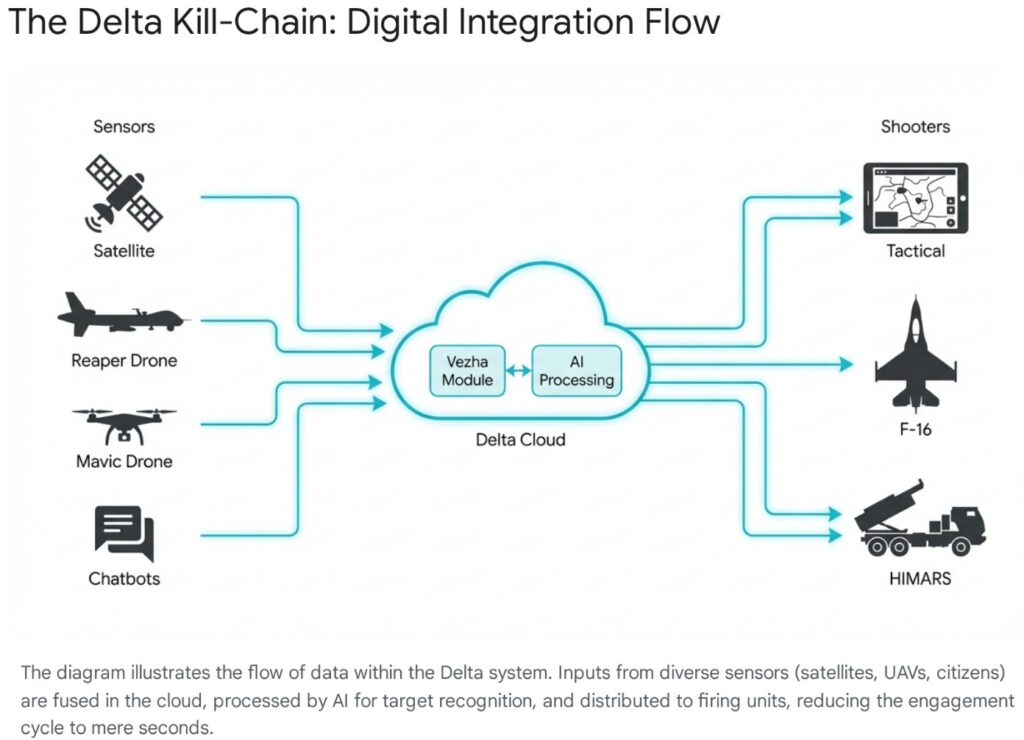

While Russia struggles with brittle command and control (C2) structures that rely on top-down rigidity and often lack horizontal communication, Ukraine has fully embraced network-centric warfare through its indigenous Delta system. By late 2025, Delta has evolved from a simple situational awareness tool into a comprehensive digital battle command platform that is attracting international customers and redefining NATO standards.10

5.1 The “Google for Military”

Delta is a cloud-based system that integrates real-time data from a vast array of sources: commercial and military satellite imagery, drone feeds, human intelligence reports (HUMINT), and sensors from Western-supplied equipment like counter-battery radars. It fuses this data into a “common operating picture” (COP) accessible to units down to the platoon level via secure tablets and terminals.34

The system’s most revolutionary contribution is the drastic reduction of the sensor-to-shooter cycle. In late 2025, the system demonstrated the ability to detect Russian hardware as unique units with an average detection time of just 2.2 seconds using AI-powered auto-detection algorithms.35 This speed is lethal in modern artillery duels; it allows Ukrainian gunners to engage Russian batteries effectively the moment they unmask, often before they can fire a second salvo or displace. This capability acts as a force multiplier, partially offsetting Russia’s lingering quantitative advantage in artillery tubes and ammunition stocks.

5.2 NATO Interoperability and Export Potential

In a reversal of the traditional “teacher-student” dynamic, NATO forces are now learning from the Ukrainian experience. Delta was successfully tested during NATO’s CWIX (Coalition Warrior Interoperability eXercise) and REPMUS 2025 exercises, where it coordinated over 100 unmanned platforms across maritime, air, and land domains.33 The system proved fully compatible with German, Polish, and Turkish C2 systems, validating its open-architecture design.

Crucially, in April 2025, an unnamed NATO member formally requested to acquire the Delta system, marking the first major export of Ukrainian digital defense technology.10 This signals that Ukraine’s “battle-forged” software is now considered superior to some peace-time systems developed by established Western defense contractors, validating Ukraine’s status as a burgeoning defense-tech power.

6. The “Zoo” Dilemma: Logistics and The Burden of Diversity

While innovation drives Ukraine forward, the legacy of emergency aid acts as a significant drag on operational efficiency. The Ukrainian military operates what Defense Minister Rustem Umerov and soldiers alike refer to as a “zoo”—a chaotic menagerie of incompatible platforms from dozens of donor nations.9 This logistical complexity stands in stark contrast to the relative homogeneity of Russian equipment, even as the latter degrades in quality.

6.1 The Armored Logistics Nightmare

By late 2025, the Ukrainian armored fleet includes Leopard 1s and 2s (German), Challenger 2s (British), M1 Abrams (American), PT-91s (Polish), CV90s (Swedish), and a vast array of Soviet-era T-72s, T-64s, and T-80s.9 This diversity creates a nightmare for maintainers:

- Incompatible Supply Chains: Each of these platforms requires different sets of tools (metric vs. imperial), specific hydraulic fluids, unique engine parts, and specialized diagnostic software. A mechanic trained on a Leopard 2 diesel engine cannot intuitively repair the gas turbine of an Abrams.9

- Maintenance Bottlenecks: To address deep maintenance needs, a Leopard 2 repair center was established in Lithuania. However, the transit time to transport a damaged tank from the Donbas to the Baltic states and back keeps critical assets off the battlefield for weeks or even months.38

- The “Universal Mechanic”: To mitigate these delays, Ukraine has deployed mobile repair workshops closer to the front, capable of handling minor to moderate repairs. These units are staffed by mechanics who have had to become “universal experts,” learning to jury-rig repairs across a dozen different systems. This adaptability is commendable but inefficient compared to a standardized fleet.39

7. The Air Power Transition: Infrastructure and Integration

The Ukrainian Air Force in late 2025 is navigating a fragile transition from a Soviet-era fleet to a mixed Western-Soviet force. The integration of F-16s (donated by Denmark, the Netherlands, and Norway) and Mirage 2000-5Fs (from France) has provided a qualitative boost but created immense infrastructure challenges.40

7.1 Infrastructure and Dispersal

The F-16 Fighting Falcon is a delicate machine compared to the rugged Soviet MiGs. Its low-slung air intake makes it susceptible to foreign object damage (FOD), requiring pristine runways. This has necessitated a massive construction effort to upgrade airfields, pouring high-quality concrete and improving hangars while under the constant threat of Russian ballistic missile attacks.42 This infrastructure requirement limits the “dispersal” tactics Ukraine used successfully in the early war, where MiGs operated from rough improvised airstrips and highways, making the new F-16 bases obvious priority targets for the VKS.

7.2 Role Specialization and Supply Chains

The introduction of the French Mirage 2000-5F adds another layer of complexity. These aircraft are being specialized for the ground-attack role, serving as “flying launch trucks” for Western precision munitions like the SCALP-EG cruise missile and AASM Hammer glide bombs.41 This allows the F-16s to focus on air defense and anti-radiation missions (SEAD). While this division of labor optimizes the strengths of each airframe, it burdens the logistics system with two completely separate Western aviation supply chains—one American/NATO standard and one French—on top of the existing supply lines for the legacy Su-27 and MiG-29 fleet.43

8. The Human Element: Mobilization and the “Booking” System

Perhaps the most critical difference between the Ukrainian and Russian war efforts in 2025 is the management of human capital. While Russia continues to rely on a “crypto-mobilization” strategy—using high financial incentives to recruit contract soldiers from impoverished regions—Ukraine faces a tighter demographic constraint and has had to implement a sophisticated legal framework to balance the needs of the trench with the needs of the factory.44

8.1 The “Booking” (Reservation) System

To protect its booming defense industry from the manpower hunger of the front lines, the Ukrainian government introduced an updated “booking” mechanism (Resolution #1608) in late 2025. This system allows critical enterprises—specifically in the Defense Industrial Complex (DIC)—to reserve key employees from mobilization.45

- Efficiency Improvements: The new rules grant a 45-day window for employees to correct military registration discrepancies without fear of immediate conscription and remove the cumbersome 72-hour waiting period for verifying reservation lists.45

- Strategic Intent: This policy acknowledges a fundamental reality of modern war: a skilled welder at a drone factory or a software engineer working on the Delta system contributes more to the war effort in the rear than they would as a rifleman in a trench. It represents a shift towards a “total defense” economy where the labor force is managed as a strategic asset.

However, this system is not without friction. The labor shortage remains acute across the broader economy. With the mobilization age lowered and enforcement stricter, businesses outside the critical defense sector struggle to retain staff, creating economic drag that threatens the tax base needed to fund the military’s domestic expenditures.44

9. Comparative Analysis: Why the Differences are Marked

The user’s query posits that the differences between the Russian and Ukrainian reports will be “marked.” The evidence supports this conclusion unequivocally. The divergence stems from the different constraints and opportunities facing each nation.

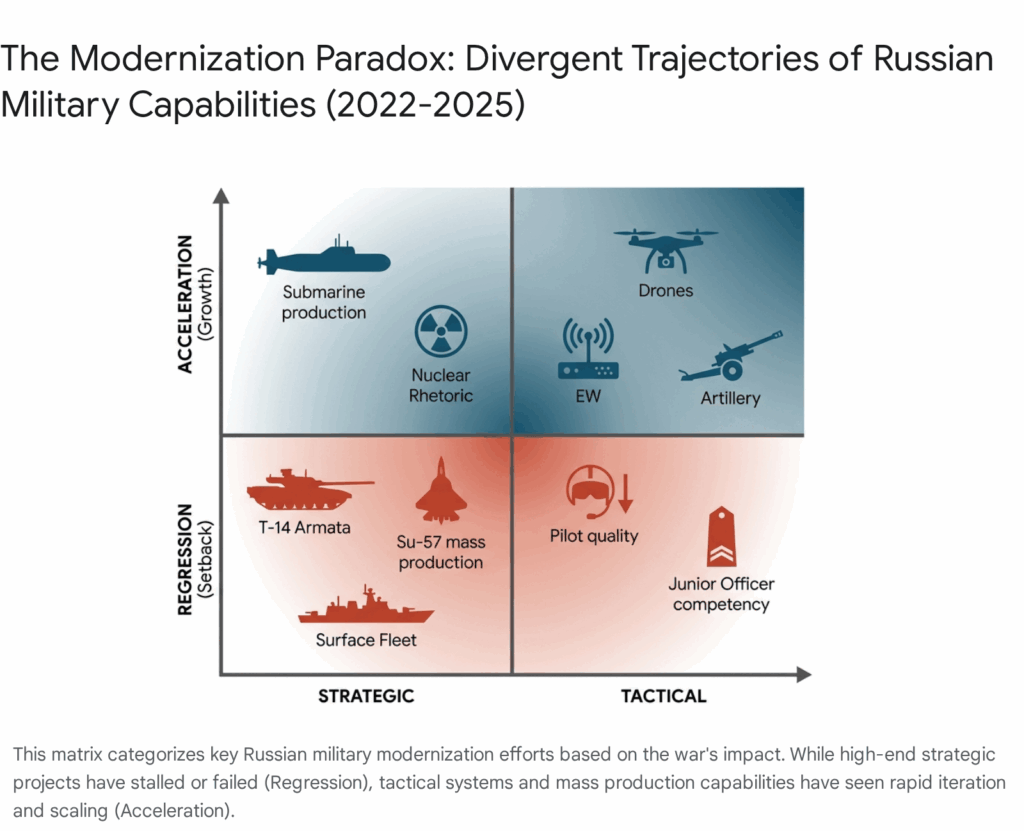

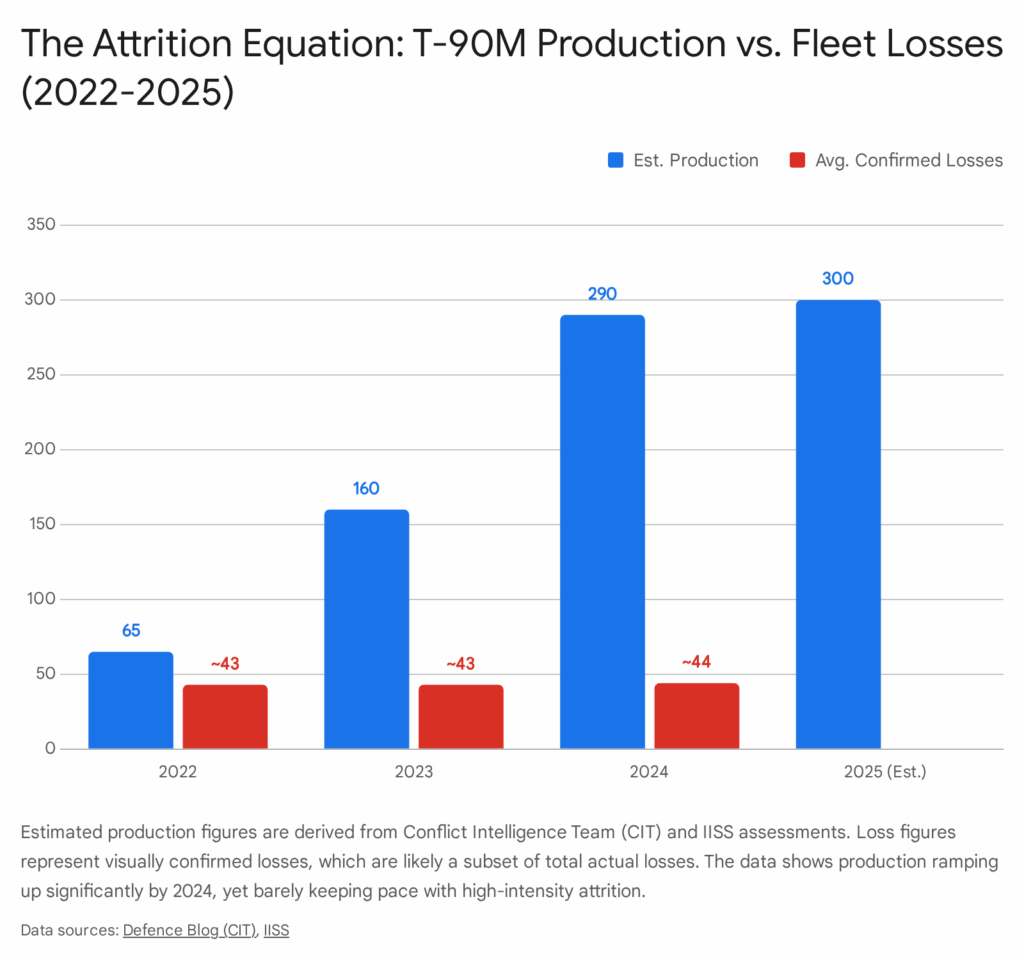

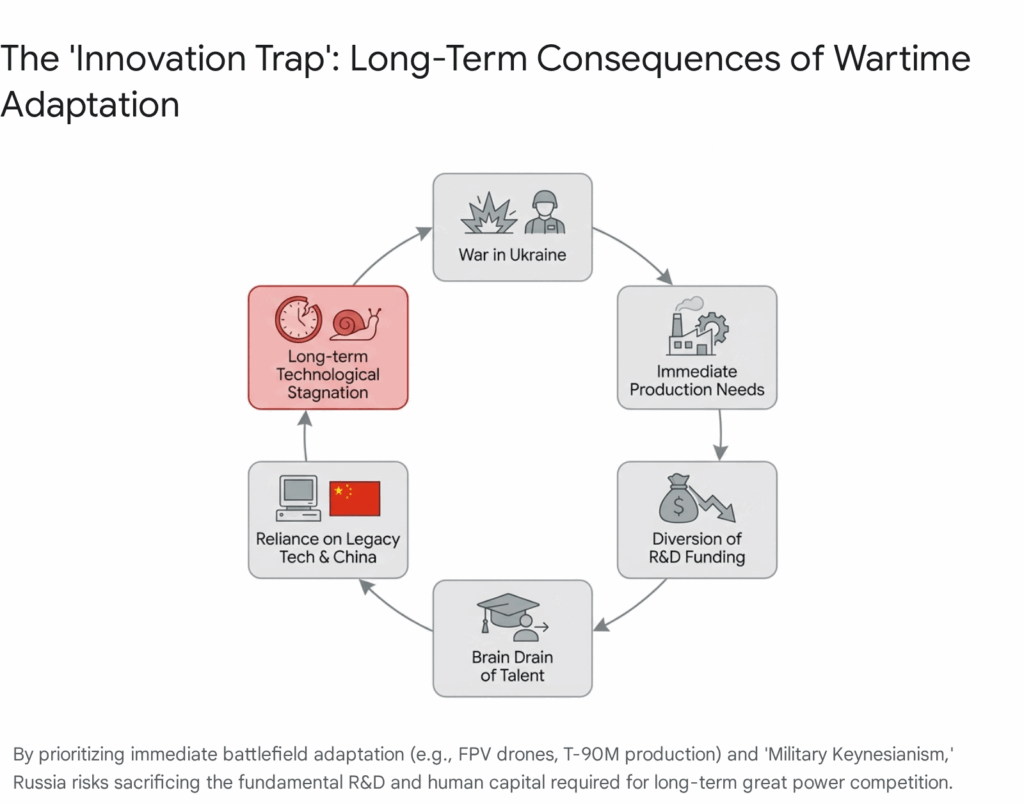

Russia is adapting by regression and scaling.

Confronted with high-tech sanctions, a “brain drain” of skilled tech workers, and a reliance on vast Soviet stockpiles, Russia has chosen a path of simplification. It produces more of less capability. The widespread factory-standard installation of “cope cages” on T-62 tanks and the use of “meat grinder” assault tactics are symptomatic of a system that prioritizes mass over survivability or precision.7 Russian innovation is largely reactive—adapting EW to jam Western GPS munitions, for instance—rather than structural.48

Ukraine is adapting by evolution and integration.

Lacking the strategic depth of Soviet stockpiles to play the mass game, Ukraine has been forced to innovate to survive. It has integrated Western precision technology with its own rapid software development capabilities (Delta) and cost-effective strike solutions (missile-drones).

- The “Zoo” as a Catalyst: While the “zoo” of Western equipment is a logistical nightmare, it has ironically forced Ukraine to become the most adaptable military in the world. Ukrainian maintainers and operators have developed a unique institutional flexibility, capable of integrating disparate systems—French missiles on Soviet jets, American radars with Ukrainian software—into a single coherent kill chain.

- Sovereignty Reclaimed: The shift from “begging for ATACMS” to “firing Sapsans” marks the psychological and strategic pivot of 2025. Ukraine is no longer asking for permission to strike the enemy; it is building the capacity to do so on its own terms.

10. Conclusion

In late 2025, the Ukrainian military is a paradoxical entity. It is simultaneously struggling with the friction of a heterogeneous, donor-dependent arsenal and leading the world in the application of digital, unmanned, and precision warfare. It is a force built not on the uniformity of the past, like its Russian adversary, but on the agile, chaotic, and lethal diversity of the future. The transition from a recipient of aid to a producer of capabilities—epitomized by the combat debut of the Sapsan missile and the export of the Delta system—suggests that while Russia is preparing for a long war of attrition, Ukraine is preparing for a war of technological decision.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- Wartime Zapad 2025 Exercise: Russia’s Strategic Adaptation and …, accessed December 20, 2025, https://my.rusi.org/resource/wartime-zapad-2025-exercise-russias-strategic-adaptation-and-nato.html

- Russian Defense Industry Sees Sharp Production Decline After …, accessed December 20, 2025, https://militarnyi.com/en/news/russian-defense-industry-sees-sharp-production-decline-after-three-years-of-growth/

- Ukraine’s Missile Program 2025: Arsenal, Scaling & Export Potential | The Gaze, accessed December 20, 2025, https://thegaze.media/news/ukraines-missile-program-2025-what-already-exists-what-is-maturing-to-series-production-and-where-the-export-potential-lies-after-the-war

- Recent Trends in the Development of Ukraine’s Military-Industrial Complex in an International Context – Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.kas.de/documents/d/ukraine/cacds_ukraine_mic_eng

- Russia Launches New Drone Warfare Branch to Boost Unmanned Forces – Kyiv Post, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.kyivpost.com/post/64093

- A powerful partner at Ukraine’s side – Rheinmetall, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.rheinmetall.com/en/media/stories/2023/rheinmetall-a-powerful-partner-at-ukraine-side

- How Many T-72 and T-90M Tanks UralVagonZavod Produced for the russian Army in 2024, accessed December 20, 2025, https://en.defence-ua.com/industries/how_many_t_72_and_t_90m_tanks_uralvagonzavod_produced_for_russian_army_in_2024-13088.html

- Russians Show T-62M and T-62MV Tanks Upgrades: Self-Entrenching Blades, Tank Sweeps and EW – Militarnyi, accessed December 20, 2025, https://militarnyi.com/en/news/russians-show-t-62m-and-t-62mv-tanks-upgrades-self-entrenching-blades-tank-sweeps-and-ew/

- Give Ukraine the tanks it needs, not a ‘petting zoo’ – Defense News, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.defensenews.com/opinion/commentary/2023/02/10/give-ukraine-the-tanks-it-needs-not-a-petting-zoo/

- Ukraine’s Battle-Forged DELTA System Catches NATO Eye: Export Talks Underway for Advanced Situational Awareness Platform · TechUkraine, accessed December 20, 2025, https://techukraine.org/2025/04/30/ukraines-battle-forged-delta-system-catches-nato-eye-export-talks-underway-for-advanced-situational-awareness-platform/

- Zelenskyy Confirms Ukraine Is Now Firing Its New Sapsan Homegrown Ballistic Missile Against Russia – UNITED24 Media, accessed December 20, 2025, https://united24media.com/latest-news/zelenskyy-confirms-ukraine-is-now-firing-its-new-sapsan-homegrown-ballistic-missile-against-russia-14185

- 1KR1 Sapsan – Wikipedia, accessed December 20, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1KR1_Sapsan

- Sanctions And Strikes Threaten Russia’s Sukhoi Jet Supply – Grand Pinnacle Tribune, accessed December 20, 2025, https://evrimagaci.org/gpt/sanctions-and-strikes-threaten-russias-sukhoi-jet-supply-516155

- If Zelensky’s Claim Of Using Homegrown Ballistic Missile For First Time Is True, It’s A Big Deal – The War Zone, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.twz.com/land/if-zelenskys-claim-of-using-homegrown-ballistic-missile-for-first-time-is-true-its-a-big-deal

- Ukraine’s Long-Term Path to Success: Jumpstarting a Self-Sufficient Defense Industrial Base with US and EU Support – Institute for the Study of War, accessed December 20, 2025, https://understandingwar.org/research/russia-ukraine/ukraines-long-term-path-to-success/

- Defence Secretary opens BAE Systems artillery factory in Sheffield, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.baesystems.com/en/article/defence-secretary-opens-bae-systems-sheffield

- Joint venture in the Ukraine – Rheinmetall, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.rheinmetall.com/en/media/news-watch/news/2024/02/2024-02-19-joint-venture-in-the-ukraine

- Rheinmetall delays Ukraine factory launch due to location change – AgroReview, accessed December 20, 2025, https://agroreview.com/en/newsen/rheinmetall-explains-the-delay-launching/

- “We were told that a new construction site would be designated very quickly.” Rheinmetall CEO explains why the plant launch in Ukraine is delayed and what it will produce there | dev.ua, accessed December 20, 2025, https://dev.ua/en/news/nam-skazaly-shcho-nove-mistse-dlia-budivnytstva-bude-pryznacheno-duzhe-shvydko-kerivnyk-rheinmetall-poiasnyv-z-chym-poviazana-zatrymka-zapusku-zavodu-v-ukraini-1762510818

- Construction of Rheinmetall plant in Ukraine delayed: CEO names reason, accessed December 20, 2025, https://unn.ua/en/news/construction-of-rheinmetall-plant-in-ukraine-delayed-ceo-names-reason

- Lynx (Rheinmetall armoured fighting vehicle) – Wikipedia, accessed December 20, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lynx_(Rheinmetall_armoured_fighting_vehicle)

- Baykar Set to Complete Drone Factory in Ukraine by August 2025 – Militarnyi, accessed December 20, 2025, https://militarnyi.com/en/news/baykar-set-to-complete-drone-factory-in-ukraine-by-august-2025/

- Timeline for completion of Bayraktar production plant in Ukraine announced, accessed December 20, 2025, https://newsukraine.rbc.ua/news/timeline-for-completion-of-bayraktar-production-1729787400.html

- Russian strike hits Turkish drone maker Baykar’s factory in Kyiv – Türkiye Today, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.turkiyetoday.com/world/russian-strike-hits-turkish-drone-maker-baykars-factory-in-kyiv-3206097

- Turkish drone maker pledges to rebuild destroyed Ukraine factory, accessed December 20, 2025, https://turkishminute.com/2025/10/13/turkish-drone-maker-pledges-to-rebuild-destroyed-ukraine-factory/

- BAE Systems establishes local presence and signs agreements to support Ukraine, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.baesystems.com/en/article/bae-systems-establishes-local-presence-and-signs-agreements-to-support-ukraine

- Ukraine, UK agree on joint artillery production – Defence Blog, accessed December 20, 2025, https://defence-blog.com/ukraine-uk-agree-on-joint-artillery-production/

- Russia’s War Transforms Ukraine into a World-Leading Military Producer | RealClearDefense, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2025/10/07/russias_war_transforms_ukraine_into_a_world-leading_military_producer_1139249.html

- Unmanned Systems Forces have become a separate branch of the Armed Forces of Ukraine – Militarnyi, accessed December 20, 2025, https://militarnyi.com/en/news/unmanned-systems-forces-have-become-a-separate-branch-of-the-armed-forces-of-ukraine/

- Ukraine unites Unmanned Systems Forces with top ‘Drone Line’ units under new command group – The Kyiv Independent, accessed December 20, 2025, https://kyivindependent.com/ukraine-creates-new-grouping-of-unmanned-systems-forces/

- Why Ukraine is Establishing Unmanned Forces Across Its Defense Sector and What the United States Can Learn from It – CSIS, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/why-ukraine-establishing-unmanned-forces

- Russian Efforts to Centralize Drone Units May Degrade Russian Drone Operations | ISW, accessed December 20, 2025, https://understandingwar.org/research/russia-ukraine/russian-efforts-to-centralize-drone-units-may-degrade-russian-drone-operations-2/

- Ukrainian combat system DELTA became primary command platform for combined multinational team at NATO exercises | MoD News, accessed December 20, 2025, https://mod.gov.ua/en/news/ukrainian-combat-system-delta-became-primary-command-platform-for-combined-multinational-team-at-nato-exercises

- Battlefield Innovation: Ukraine’s DELTA System Paves the Way for Allied Interoperability at CWIX24 – NATO’s ACT, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.act.nato.int/article/delta-system-cwix/

- Ukrainian DELTA system has verified over 130000 Russian targets hit in two months, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.pravda.com.ua/eng/news/2025/10/08/8001757/

- The EU Military Assistance Mission for Ukraine – A peace actor who teaches to fight, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.delorscentre.eu/en/publications/the-eu-military-assistance-mission-for-ukraine

- Can Ukraine maintain and optimally use its modern Western tanks? – The Kyiv Independent, accessed December 20, 2025, https://kyivindependent.com/can-ukraine-make-optimal-use-of-western-tanks-and-attack-vehicles/

- Lithuania Will Soon Build More German Leopard Tanks – The National Interest, accessed December 20, 2025, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/lithuania-will-soon-build-more-german-leopard-tanks-ps-121925

- Tanks, missiles, sanctions and motivated engineers: inside the world of Russian weapons production | Ukrainska Pravda, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.pravda.com.ua/eng/articles/2025/11/14/8007314/

- A Look Ahead For The Ukranian Air Force In 2025 – Simple Flying, accessed December 20, 2025, https://simpleflying.com/look-ahead-ukranian-air-force-2025/

- Ukrainian Air Force receives its first Mirage 2000s and more F-16s – Euro-sd, accessed December 20, 2025, https://euro-sd.com/2025/02/major-news/42468/ps-zsu-gets-first-mirage-2000s/

- Cases For (and Against) F-16, Gripen and Mirage in Ukraine – Großwald, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.grosswald.org/is-the-runway-long-enough-the-case-for-and-against-the-f-16-in-ukraine-next-swedish-gripen-and-french-mirage-fighter-jets/

- How to enhance the Ukrainian Air Force? – Defence24.com, accessed December 20, 2025, https://defence24.com/armed-forces/how-to-enhance-the-ukrainian-air-force

- Army at a crossroads: the mobilisation and organisational crisis of the Defence Forces of Ukraine | OSW Centre for Eastern Studies – Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-commentary/2025-03-14/army-a-crossroads-mobilisation-and-organisational-crisis

- Policy Win: Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine Updated Employees Reservation Rules to Support the Defense Industry Workforce Potential, accessed December 20, 2025, https://chamber.ua/success-stories/policy-win-cabinet-of-ministers-of-ukraine-updated-employees-reservation-rules-to-support-the-defense-industry-workforce-potential/

- Accelerated reservation for businesses: 45-day mechanism for the defense industry and cancellation of the 72-hour check | Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.kmu.gov.ua/en/news/pryskorene-broniuvannia-dlia-biznesu-45-dennyi-mekhanizm-dlia-opk-ta-skasuvannia-72-hodynnoi-perevirky

- How Ukraine’s New Mobilization Law Impacts Human Rights and Global Food Systems, accessed December 20, 2025, https://just-access.de/how-ukraines-new-mobilization-law-impacts-human-rights-and-global-food-systems/

- Seven Contemporary Insights on the State of the Ukraine War – CSIS, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/seven-contemporary-insights-state-ukraine-war