EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Tactical Training Industrial Complex: An Analyst’s Perspective

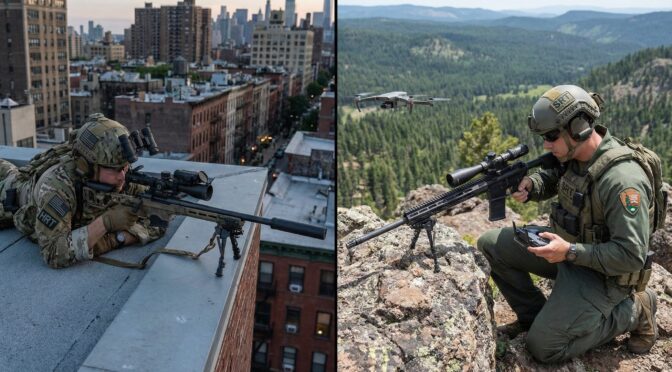

The landscape of law enforcement tactical training in the United States has undergone a radical transformation in the post-Global War on Terror (GWOT) era. We are no longer in an era where static qualification on a square range constitutes operational readiness. The contemporary tactical officer faces an asymmetrical threat environment characterized by ambushes, active killers with sophisticated weaponry, and a legal landscape that demands perfection in decision-making under extreme duress. Consequently, the training industry has bifurcated. On one side, legacy academies continue to provide the foundational doctrine of marksmanship and manipulation. On the other, a cadre of itinerant Subject Matter Experts (SMEs)—often hailing from Tier 1 Special Operations units—are delivering “bleeding edge” tactics focused on cognitive processing, entangled combat, and opposed Close Quarters Battle (CQB).

This report serves as a strategic analysis of the top 20 tactical training programs available to U.S. law enforcement officers today. As operational analysts, we do not evaluate these programs solely on their ability to teach an officer how to shoot tight groups on paper. Rather, we evaluate them on survivability: the extent to which the curriculum prepares an officer to process information, navigate complex physical environments, and neutralize threats while adhering to use-of-force policies.

The methodology employed for this assessment is exhaustive. It integrates direct curriculum review with a rigorous Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) analysis of the “tactical social graph.” By monitoring discussions on platforms such as Reddit (r/tacticalgear, r/CQB, r/AskLE), Primary & Secondary forums, and industry podcasts, we have calculated the “street credibility” of these programs. In the tactical community, reputation is currency; a program that fails to deliver relevant, battle-proven content is quickly dissected and discarded by the end-user community.

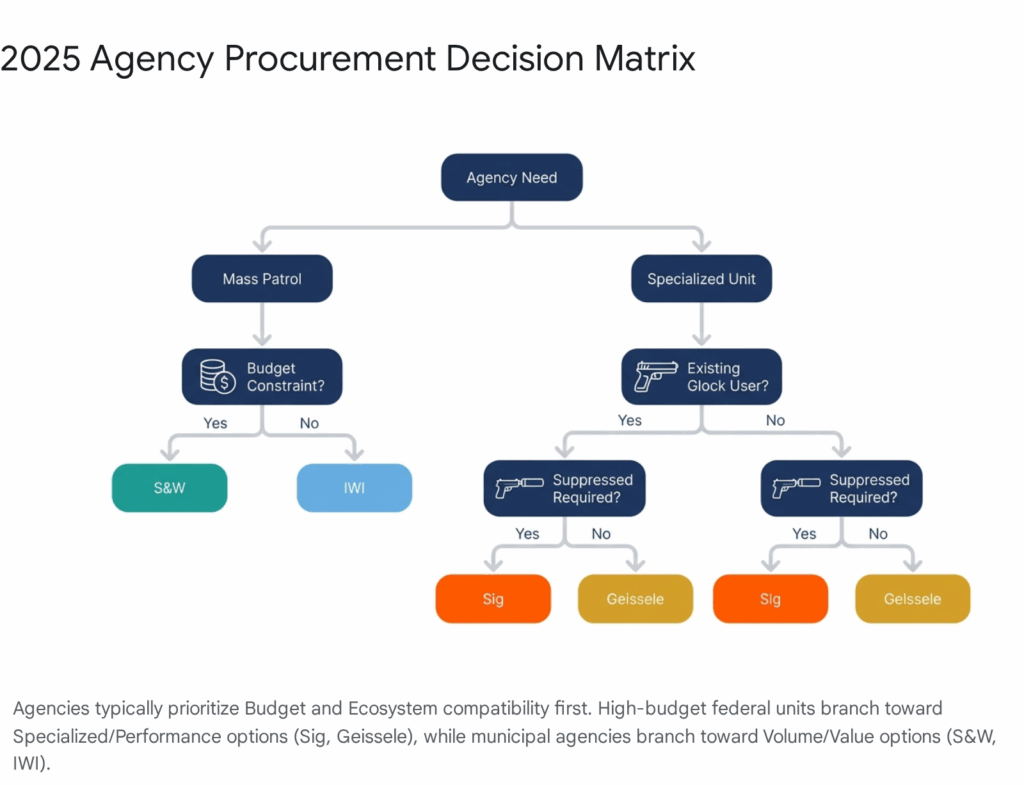

This report categorizes training into three distinct tiers of curriculum—Introduction, Moderate, and Advanced—and clearly delineates between private sector entities and those deeply integrated with military contracts. The ranking from 1 to 20 reflects a weighted matrix favoring operational relevance, instructor pedigree, facility capabilities, and the “thinking enemy” methodology.

METHODOLOGY AND RANKING CRITERIA

The Analytical Framework

To establish a definitive ranking of the top 20 programs, we utilized a four-point assessment matrix. This ensures that a specialized itinerant instructor can be fairly compared against a massive federal facility.

- Operational Relevance (40%): Does the training address the most pressing threats facing modern LEOs? This includes Vehicle CQB (VCQB), low-light/no-light operations, and counter-ambush tactics. Programs that rely on antiquated “range theater” are penalized.

- Curriculum Depth (30%): The clarity and progression of the training path. A superior program offers a logical crawl-walk-run progression from introductory skills to advanced synthesis.

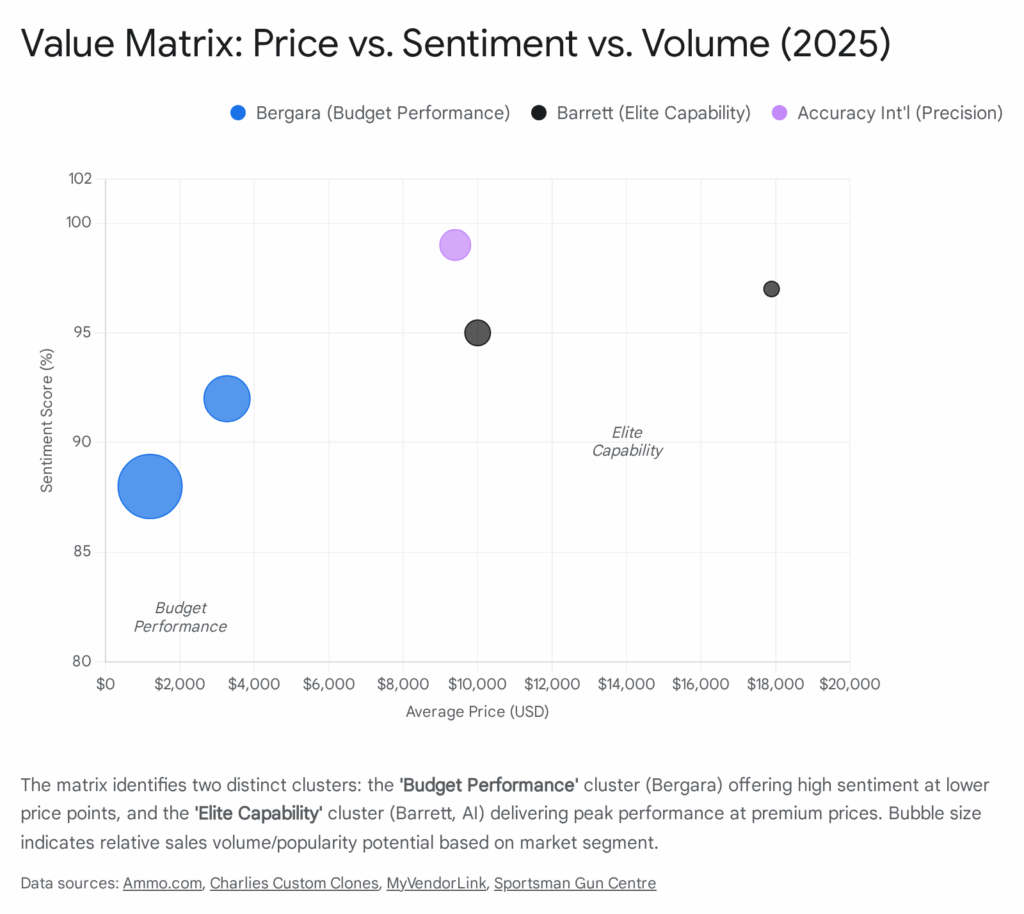

- Social Media Sentiment & OSINT (20%): A qualitative calculation of the program’s reputation among verified professionals. This involves analyzing After Action Reports (AARs) for keywords such as “humbling,” “liability,” “relevant,” and “life-saving,” versus negative markers like “fudd,” “dated,” or “cash grab.”

- Pedagogical Transfer (10%): The ability of the cadre to transfer knowledge. It is insufficient for an instructor to be a skilled shooter; they must be an effective teacher capable of diagnosing student failure points.

TIER 1: THE APEX PREDATORS (RANK 1-5)

The top five programs represent the gold standard in American tactical training. These entities influence doctrine at a national level and are the primary sources of innovation for SWAT teams and patrol officers alike.

1. DIRECT ACTION RESOURCE CENTER (DARC)

Sector: Private Sector (Heavy Military Integration)

Location: North Little Rock, Arkansas

Focus: Counter-Terrorism, Advanced SWAT, Night Vision, Large-Scale CQB

Operational Profile

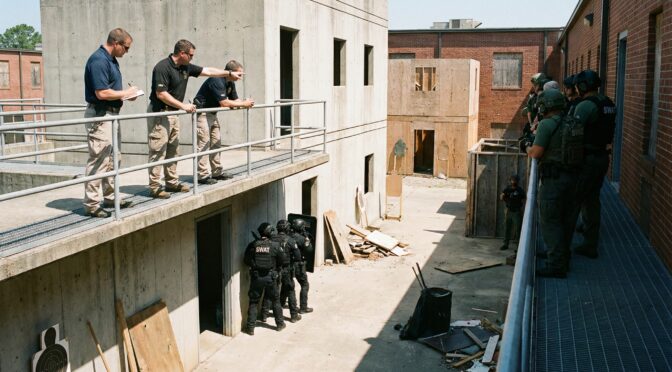

The Direct Action Resource Center, universally known as DARC, occupies a unique space in the training landscape.1 It is widely regarded by industry insiders as the “graduate school” of tactical operations. Unlike standard shooting academies that focus on individual marksmanship, DARC focuses on warfare within a domestic and counter-terrorism context. The facility acts as a massive laboratory for urban combat, featuring extensive mock villages and complex structures designed to simulate multi-story, multi-breach point operational environments.

DARC’s primary distinction is its proprietary methodology regarding “Structure Domination.” While traditional law enforcement doctrine often emphasizes “slow and methodical” clearing (slicing the pie), DARC teaches “flood” tactics necessary to counter a swarming terrorist attack or a determined, fortified defender. This shift in philosophy addresses the “tactical decision-making” gap identified in major incident reviews, where hesitation often leads to officer casualties.

Curriculum Architecture

The DARC curriculum is rigid, tiered, and scientifically structured to induce stress and force operational adaptation.

- Introduction (Level 1): Law Enforcement Counter Terrorism Course (LECTC) Level 1. Do not let the “Level 1” designation mislead; this is an advanced course by industry standards.2 It serves as the “Introduction” to the DARC methodology but requires officers to be proficient in basic SWAT tasks. The curriculum covers the fundamentals of multi-team interior dominance, hallway movement, and the integration of explosive breaching. It introduces the student to the “thinking enemy” concept, where opposing forces (OpFor) do not act as static targets but actively counter-attack.3

- Moderate: Tactical Urban Sustainment Course (TUSC). This curriculum bridges the gap between tactical operations and urban survival. It is designed for officers who may be cut off or operating in non-permissive urban environments (e.g., massive civil unrest or post-disaster scenarios).1 It covers operational logistics, unconventional planning, and sustainment while maintaining a low signature.

- Advanced: LECTC Level 2. This is the apex of domestic SWAT training. LECTC-2 expands on the Level 1 foundation by introducing complex environmental problems—specifically, low-light and no-light operations using night vision.4 The operational tempo is grueling, often involving 24-hour cycles that test a team’s endurance and decision-making under extreme fatigue. It integrates sniper support directly into the assault flow, requiring seamless communication between the “green” (assault) and “long rifle” elements.

Social Media & OSINT Sentiment Analysis

Discussion Level: Very High.

Sentiment Score: 10/10 (Unanimous Professional Acclaim).

Analysis of discussions on platforms like Reddit (r/tacticalgear, r/CQB) and specialized forums reveals a reverence for DARC that borders on cult-like status.

- The “DARC Arc”: A common theme in AARs is the psychological pressure of the course. Users describe a phenomenon where the intensity of the OpFor forces teams to abandon “range theatrics” and resort to primal, effective communication.5

- Example Commentary: One verified user on r/CQB noted, “DARC is a thinking man’s game. The OpFor doesn’t just sit in a room waiting to die. They counter-attack, they flank, they use the building against you. It exposed flaws in our department’s SOPs within the first hour”.5

- Negative Indicators: Virtually nonexistent regarding the quality of training. The only “complaints” revolve around the physical toll (“The bruises lasted for weeks”) and the difficulty of securing a slot due to high demand from Tier 1 military units.

Military vs. Private Sector Integration

DARC is a private sector entity with profound military integration. It is a primary training hub for Special Operations Forces (SOF) and Federal agencies. The “training technology” developed here for military counter-terrorism units is filtered down to the LE courses, ensuring cops are learning tactics validated on global battlefields.1

Analyst Verdict

Rank: #1. DARC is the number one program because it addresses the “Swarm” threat—coordinated attacks (like Mumbai or Paris) that standard patrol tactics cannot handle. It provides the most realistic force-on-force training environment in the country.

2. ALLIANCE POLICE TRAINING

Sector: Municipal Government (Open to Sworn/Vetted Civilians)

Location: Alliance, Ohio

Focus: Hosting Tier 1 Itinerant Instructors, Shoothouse Operations, Integrated Defense

Operational Profile

Alliance Police Training represents a paradigm shift in the industry and is arguably the most significant development in modern LE training.6 It is not a private academy; it is the training division of the Alliance (Ohio) Police Department. Under the visionary leadership of Training Director Joe Weyer, Alliance has transformed a municipal range into a national “university” for tactical training.7

Instead of relying solely on in-house staff to teach a static doctrine, Alliance curates the market. They identify the absolute best Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) in the world—experts in shotgun, red dots, low light, ballistics—and host them at their facility. This “Hub Model” allows a patrol officer from the Midwest to access training that was previously available only to elite coastal units or federal teams.

Curriculum Architecture

Because Alliance hosts external instructors, the curriculum is vast. However, the facility itself structures training through its facility capabilities.

- Introduction: Patrol Rifle/Pistol Qualifications.

Taught by Alliance PD staff, these courses establish the baseline safety and manipulation standards required to operate on the range. - Moderate: Shoothouse Orientation. Before students can take advanced CQB courses in the Alliance shoot house, they must undergo safety orientation. This facility is world-class, featuring complex geometry, breeching doors, and cat-walks for instructor observation.8

- Advanced: The “Visiting Professor” Series.

This is the core value proposition. Alliance hosts advanced courses such as:

- Presscheck Consulting: No Fail Pistol (Accountability).9

- Centrifuge Training: Vehicle CQB (Fighting around cars).10

- EAG Tactical / Ridley: Shoothouse CQB (Team tactics).

- Sentinel Concepts: Low Light / Shotgun.

Social Media & OSINT Sentiment Analysis

Discussion Level: High.

Sentiment Score: 9.9/10 (Cult Status).

“The Alliance Schedule” is a major topic of discussion on P&S (Primary & Secondary) forums annually. It is viewed as a vetting mechanism; if an instructor is invited to Alliance, they are “good to go.”

- Facility Praise: Users consistently laud the facility’s amenities—climate-controlled cleaning rooms, the “team room” atmosphere, and the professionalism of the host staff.

- Example Commentary: “If you live in the Midwest and aren’t training at Alliance, you are wrong. Joe Weyer has built a Mecca. You get Pressburg one week and Steve Fisher the next, all with police-grade facilities”.8

- Community Defense: The community is fiercely protective of Alliance. When online detractors question the relevance of open-enrollment training, Alliance alumni are quick to defend the rigor and liability-consciousness of the facility.

Military vs. Private Sector Integration

Alliance is a government entity (Municipal PD) that partners with the private sector. It frequently hosts military units (National Guard, SOF) for pre-deployment workups due to the quality of the shoot house, but its primary identity is LE-centric.7

Analyst Verdict

Rank: #2. Alliance ranks #2 because it democratizes access to Tier 1 training. It has effectively destroyed the excuse that “good training is too far away.” It proves that a municipal agency can build a world-class program through smart partnerships.

3. GUNSITE ACADEMY

Sector: Private Sector

Location: Paulden, Arizona

Focus: The Modern Technique of the Pistol, General Firearms Manipulation, Mindset

Operational Profile

Gunsite is the “Harvard” of the firearms world.11 Founded by Col. Jeff Cooper in 1976, it established the “Modern Technique” of the pistol (Weaver stance, flash sight picture, compressed surprise break) which forms the DNA of almost all modern police shooting. While tactical trends come and go, Gunsite remains the bedrock of pedagogical consistency.

The facility is massive, sprawling over thousands of acres of high desert, featuring dozens of ranges and specialized tactical simulators (natural terrain courses called “The Donga” and “The Scrambler”).12

Curriculum Architecture

Gunsite’s curriculum is the most structured in the industry, relying on a strict prerequisite system.

- Introduction: 250 Defensive Pistol. The standard by which all others are measured. This five-day course focuses intensely on the draw, presentation, stance, and trigger control. It is not just a shooting class; it is a “mindset” class, drilling the Color Code of mental awareness.13

- Moderate: 350 Intermediate Pistol and Close Quarters Pistol (CQP). Once the basics are mastered, students move to CQP, which introduces retention shooting, movement, and low-light scenarios. The Active Shooter curriculum for School Resource Officers (SROs) falls here, focusing on single-officer response to mass casualty events.14

- Advanced: Advanced Team Tactics and Laser/Night Vision. These courses integrate individual skills into team movements. The Advanced Team Tactics course builds on the 250/350 foundation to teach two-man team dynamics, essential for patrol officers who often arrive in pairs.14

Social Media & OSINT Sentiment Analysis

Discussion Level: Very High.

Sentiment Score: 9.5/10 (Revered Legacy).

Discussions often revolve around the “Gunsite Family” experience. Alumni are fiercely loyal.

- Critique: Some younger tactical officers on Reddit critique the “Weaver stance” legacy, arguing that the modern Isosceles stance is superior for body armor presentation. However, almost all acknowledge the mental conditioning is superior.11

- Example Commentary: “I’ve taken high-speed courses from Unit guys, but Gunsite 250 is where I learned to actually run my gun without thinking. It builds the neural pathways like nowhere else”.15

- Sentiment: Users describe the experience as “drinking from a firehose” but praise the logical layering of skills.

Military vs. Private Sector Integration

Gunsite is a private entity. While it trains military units (specifically the Foreign Weapons courses), its heart is in the private citizen and law enforcement sectors.16

Analyst Verdict

Rank: #3. You cannot be an advanced operator without mastering the basics. Gunsite teaches the basics better than anyone in the world. Their adherence to “The Combat Triad” (Marksmanship, Gun Handling, Mindset) ensures graduates are safe and reliable partners in a fight.

4. SIG SAUER ACADEMY (SSA)

Sector: Private Sector (Industry Owned)

Location: Epping, New Hampshire

Focus: Comprehensive Small Arms, VTAC Integration, Instructor Development

Operational Profile

Sig Sauer Academy is the “Disneyland for Shooters”.11 As the training arm of the firearms manufacturer, they have limitless resources. Their facility features state-of-the-art indoor ranges, tactical bays, a maritime training area, and a 1,000-yard precision rifle range. SSA has successfully bridged the gap between civilian competition shooting and law enforcement tactics, offering a polished, corporate, yet highly lethal product.

Curriculum Architecture

SSA uses a granular numbering system (100 series) akin to a university.

- Introduction: Handgun 101-104. This progression allows officers to test out of lower levels if proficient. Handgun 104 is a rigorous skills test that serves as a gatekeeper for advanced work.17

- Moderate: Semi-Auto Rifle Instructor and Skill Builder.

SSA is a primary source for LE instructor certifications in the Northeast. Their Red Dot Sight transition courses are currently in high demand as agencies migrate to pistol optics. - Advanced: VTAC Streetfighter and Master Pistol Instructor. Through a partnership with Kyle Lamb (Viking Tactics), SSA hosts the high-aggression Streetfighter course, which focuses on working around vehicles and barricades.18 The Master Pistol Instructor qualification is arguably the most difficult shooting qualification in the industry, requiring mastery of every platform.

Social Media & OSINT Sentiment Analysis

Discussion Level: High.

Sentiment Score: 9/10.

- Themes: High praise for the “pro shop” and the ability to test any Sig firearm. Instructors are noted for being “zero ego” compared to some other industry figures.

- Example Commentary: “Took the Rifle Instructor course. The facility is insane. We were shooting indoors, outdoors, dealing with malfunctions, and the instructors were all top-tier LE/Mil. The cafeteria alone is worth the trip”.11

- Negative: Some purists argue the curriculum can feel “corporate,” but few deny the effectiveness.

Military vs. Private Sector Integration

SSA is heavily integrated with both. They hold major contracts for military transition training (especially with the adoption of the P320/M17 system) and serve as a primary training hub for federal agencies in New England.19

Analyst Verdict

Rank: #4. Accessibility and quality. SSA provides a massive volume of standardized, high-quality training. Their “Master Instructor” coin is a legitimate badge of honor that carries weight on a resume.

5. NORTHERN RED

Sector: Private Sector (Itinerant)

Location: Mobile (Based in NC/VA)

Focus: Opposed CQB, Small Unit Tactics, Carbine Employment

Operational Profile

Northern Red represents the “Tier 1” influence on law enforcement. Staffed primarily by former US Army Special Forces (Green Berets) and Delta Force (CAG) operators 20, Northern Red brings the lessons of the Global War on Terror directly to police SWAT teams. Their philosophy rejects the “dance” of empty room clearing and focuses entirely on fighting a resisting opponent.

Curriculum Architecture

- Introduction: Gunfighter Carbine/Pistol.

Heavily focused on mechanics, recoil management, and “driving the gun.” They teach a very specific, aggressive style of shooting derived from JSOC (Joint Special Operations Command) standards. - Moderate: Tactical Team Foundations. This moves the focus from the individual to the element. It covers small unit movement, communication, and sectors of fire in open and urban terrain.21

- Advanced: Opposed CQB. This is their flagship. Using Simunitions, students clear structures against role players who fight back. The training emphasizes “limited penetration” (fighting from the threshold) rather than “dynamic entry” (running into the room), which aligns with modern officer safety priorities.22

Social Media & OSINT Sentiment Analysis

Discussion Level: Moderate (Niche).

Sentiment Score: 9/10.

- Themes: “Intensity.” Northern Red AARs describe a high-testosterone, no-nonsense environment.

- Example Commentary: “They treat you like adults, but they expect you to perform. The opposed runs showed us that our ‘slow and methodical’ clearing would get us killed. They vet their tactics with resistance, not theory”.22

- Key Insight: Users note that Northern Red instructors (like Tom Spooner) are excellent at translating combat tactics to LE “Use of Force” constraints, avoiding the “military cos-play” trap.

Military vs. Private Sector Integration

Northern Red is a private company that trains elite military units. They are effectively exporting “Unit” TTPs (Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures) to the law enforcement market.20

Analyst Verdict

Rank: #5. They are the bridge. Northern Red is critical for SWAT teams that need to understand how to handle hardened, barricaded subjects. Their emphasis on “Opposed” training is vital for realism.

TIER 2: THE SPECIALISTS (RANK 6-12)

This tier consists of programs that dominate a specific niche. While they may not offer a “comprehensive” academy experience like Gunsite, they are the undisputed masters of their specific domains (Vehicles, Grappling, Accountability, Night Vision).

6. SHIVWORKS (CRAIG DOUGLAS)

Sector: Private Sector (Itinerant)

Focus: Entangled Shooting, Extreme Close Quarters Concepts (ECQC)

Operational Analysis

Craig Douglas, an undercover narcotics veteran, has single-handedly defined the “entangled fight” category.23 Most police academies teach shooting at 7 yards; ShivWorks teaches shooting while an offender has you in a headlock. This is critical “moderate to advanced” training for plainclothes and patrol officers who operate at contact distance.

Curriculum

- Intro: Practical Unarmed Combat (PUC) – managing encroachment.

- Moderate: Edged Weapon Overview (EWO) – defending against knives.

- Advanced: Extreme Close Quarters Concepts (ECQC). This course combines live fire with full-contact grappling in a “FIST” suit. The “Evo” drill places a student in a car or chair, introduces an attacker, and requires the student to fight to their gun and fire.23

Analyst Verdict

Rank: #6. Essential. Most officer assaults happen at 0-5 feet. This is the only curriculum that adequately prepares an officer for that reality.

7. CENTRIFUGE TRAINING (WILL PETTY)

Sector: Private Sector (Itinerant)

Focus: Vehicle Close Quarters Battle (VCQB), Injured Shooter

Operational Analysis

Before Will Petty, “vehicle defense” meant hiding behind the engine block. Centrifuge introduced the science of ballistics through auto glass and pillars. They revolutionized how cops fight around their cruisers.24

Curriculum

- Intro: VCQB User – Ballistic lab demonstrating bullet deflection through windshields.

- Moderate: Injured Shooter – One-handed manipulation.

- Advanced: VCQB Instructor – Teaches the pedagogy of vehicle defense.10

Analyst Verdict

Rank: #7. LEOs spend 80% of their time in cars. This training is contextually essential for survivability during traffic stops and ambushes.

8. PRESSCHECK CONSULTING (CHUCK PRESSBURG)

Sector: Private Sector (Itinerant)

Focus: Accountability, Small Target Interdiction, Night Vision

Operational Analysis

Chuck Pressburg (retired SGM, Unit veteran) teaches “No Fail” pistol. The philosophy is simple: You are responsible for every round. The targets are small (B8 bulls), the standards are high, and the stress is induced by peer pressure and strict scoring.9

Curriculum

- Intro: None (Requires verified proficiency).

- Moderate: No Fail Pistol – Shooting B8s at 25 yards. Managing recoil under stress.

- Advanced: Night Fighter – White light and NVG integration.25

Analyst Verdict

Rank: #8. As police accountability rises, the ability to hit a 3×5 card at 25 yards on demand is a liability necessity. Presscheck enforces this standard.

9. TEXAS TACTICAL POLICE OFFICERS ASSOCIATION (TTPOA)

Sector: Non-Profit Association

Focus: SWAT Standards, Regional Training

Operational Analysis

TTPOA is the heavy hitter of associations. Their annual conference is a massive training event. They drive the tactical culture for the southern US.26

Curriculum

- Intro: Basic SWAT School – 60-hour indoctrination.

- Moderate: Instructor Certifications.

- Advanced: Command Level Training – Critical incident management.27

Analyst Verdict

Rank: #9. Cultural impact. They set the standard for what a SWAT officer looks like in Texas.

10. NATIONAL TACTICAL OFFICERS ASSOCIATION (NTOA)

Sector: Non-Profit Association

Focus: Standards, Certifications, Command College

Operational Analysis

NTOA is the administrative backbone of American SWAT. They publish the “SWAT Standards” used to justify budgets.28

Curriculum

- Intro: Basic SWAT.

- Moderate: Team Leader Development.

- Advanced: Command College.29

Analyst Verdict

Rank: #10. Essential for liability and administration, even if less “tactically” aggressive than DARC.

11. GREEN EYE TACTICAL

Sector: Private Focus: Night Vision, CQB Verdict: Eric Dorenbush provides the most granular NVG training available. “Crawl-walk-run” methodology is highly praised.30

12. SAGE DYNAMICS (AARON COWAN)

Sector: Private Focus: RDS Handgun, Low Light Verdict: The academic authority on Red Dot Sights. His white papers drive agency policy on optics.31

TIER 3: REGIONAL POWERS AND SPECIALIZED ACADEMIES (RANK 13-20)

13. ITTS (INTERNATIONAL TACTICAL TRAINING SEMINARS)

Location: Los Angeles, CA Focus: Urban Sniper, Problem Solving Verdict: Scott Reitz (LAPD Metro) brings the “LA SWAT” lineage. Focuses heavily on target discrimination and liability in dense urban centers.32

14. THUNDER RANCH

Location: Lakeview, Oregon Focus: Urban Rifle, Defensive Logic Verdict: Clint Smith is a legend. While some tactics are “old school,” the logic of Urban Rifle (shooting through ports, awkward positions) remains valid and highly respected.33

15. VIKING TACTICS (VTAC – KYLE LAMB)

Location: Mobile / NC Focus: Aggressive Carbine, Physicality Verdict: VTAC drills (1-5 drill, 9-hole barricade) are industry standards. Training emphasizes physical fitness and aggression.34

16. ACADEMI / CONSTELLIS (MOYOCK TRAINING CENTER)

Location: Moyock, NC Focus: Driving, Security Ops Verdict: The scale allows for driving tracks and massive ranges. Best for “hard skills” like evasive driving.13

17. CALIFORNIA ASSOCIATION OF TACTICAL OFFICERS (CATO)

Location: California Focus: West Coast Standards Verdict: The CA equivalent of TTPOA. Critical for navigating the complex political/legal landscape of policing in California.35

18. FLETC (FEDERAL LAW ENFORCEMENT TRAINING CENTERS)

Location: Glynco, GA Focus: Maritime, Federal Standards Verdict: The “Basic” for Feds. Their Marine Law Enforcement and Active Shooter programs are robust and standardized.36

19. ALERRT (ADVANCED LAW ENFORCEMENT RAPID RESPONSE TRAINING)

Location: Texas State University Focus: Active Shooter Response Verdict: The FBI’s national standard for active shooter response. Widely adopted and respected for saving lives.37

20. 88 TACTICAL

Location: Omaha, NE Focus: Behavior-Based Tactics Verdict: A massive regional hub focusing on “primal” responses and behavior-based combat.38

COMPARATIVE DATA ANALYSIS

Table 1: Operational Focus and Cost Matrix

| Rank | Program | Primary Niche | Operational Philosophy | Est. Daily Cost | Target Audience |

| 1 | DARC | Counter-Terrorism | “Thinking Enemy” / Opposed | ~$350 | SWAT / SOF |

| 2 | Alliance | Host Facility | “Best in Breed” Aggregation | ~$250 | Patrol / SWAT |

| 3 | Gunsite | Foundation | “The Modern Technique” | ~$450 | All Levels |

| 4 | Sig Sauer | Instructor Dev | “Total Systems” | ~$300 | Instructors |

| 5 | Northern Red | Small Unit Tactics | “Direct Action” | ~$300 | SWAT |

| 6 | ShivWorks | Entangled Combat | “Pressure Testing” | ~$250 | UC / Patrol |

| 7 | Centrifuge | Vehicle Ops | “Ballistic Realism” | ~$250 | Patrol |

| 8 | Presscheck | Accountability | “No Fail” Standards | ~$250 | Advanced |

| 9 | TTPOA | SWAT Standards | “Regional Standardization” | Low (Member) | Texas LE |

| 10 | NTOA | Administration | “Liability & Safety” | Low (Member) | Command |

Table 2: Social Media Sentiment & Discussion Intensity (OSINT)

| Program | Discussion Volume | Key Sentiment Keywords (Positive) | Key Sentiment Keywords (Negative) | Primary Platforms |

| DARC | Very High | “Humbling,” “Reality check,” “Lethal,” “Hardest” | “Bruising,” “Expensive,” “Hard to book” | Reddit (r/CQB), P&S |

| Gunsite | High | “Family,” “Legacy,” “Mindset,” “Professional” | “Weaver stance,” “Dated,” “Fudd?” | Forums, YouTube |

| Alliance | High | “Mecca,” “Joe Weyer,” “Facility,” “Schedule” | None (Universally praised) | P&S, Facebook |

| ShivWorks | Moderate | “Ego check,” “Painful,” “Necessary,” “Eye-opening” | “Intense,” “Not for casuals” | Reddit (r/CCW) |

| Presscheck | High | “Accountability,” “Standards,” “Hilarious lectures” | “Rude,” “Strict,” ” elitist” | Instagram, Reddit |

SECTOR ANALYSIS: MILITARY VS. PRIVATE SECTOR

Understanding the cross-pollination between military and private sectors is crucial for the analyst.

- The “Pipeline” Effect (Private Sector): Entities like Northern Red, Green Eye Tactical, and Presscheck Consulting are essentially private conduits for military intellectual property. They are staffed by retired Tier 1 operators who translate classified TTPs (Tactics, Techniques, Procedures) into unclassified, digestible curriculums for law enforcement. These programs are “Private Sector” on paper, but “Military” in DNA.

- The “Contractor” Giants (Hybrid): Academi (Constellis) and Sig Sauer Academy exist in a hybrid state. They maintain massive Department of Defense (DoD) contracts. Consequently, their facilities are built to military specifications (large caliber ranges, driving tracks) which LE agencies benefit from when they host courses.

- The “Pure” LE Sector: TTPOA, CATO, NTOA, and Alliance Police Training are purely law enforcement entities. Their doctrine is derived specifically from case law (Graham v. Connor), state standards (POST/TCOLE), and police union requirements. They prioritize liability reduction and evidence preservation over pure “combat” efficiency.

CONCLUSION

The U.S. tactical training market has matured from a monolithic industry into a specialized ecosystem. The “General Practitioner” model of the old police academy is dead. The top-tier programs identified in this report—specifically DARC, Alliance, and ShivWorks—reflect a demand for specialized, problem-centric training.

For the agency analyst or training coordinator, the data suggests a clear “Best Practices” pathway:

- Establish the Foundation at Gunsite or Sig Sauer Academy (Marksmanship).

- Develop Context through ShivWorks and Centrifuge (Environment specific).

- Refine Standards with Presscheck or Northern Red (Accountability).

- Test Integration at DARC (Full spectrum operations).

This tiered approach ensures the officer is not just a “shooter,” but a tactical problem solver capable of surviving the complex threat environment of 2026.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- Direct Action Resource Center (DARC), accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.darc-usa.com/

- AAR: DARC LECTC | – Primary & Secondary, accessed January 25, 2026, https://primaryandsecondary.com/aar-darc-lectc-2/

- Anti Terror 2: DARC Law Enforcement Counter Terrorism Course, Level 2 – YouTube, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R3M5O5RWT2o

- DARC Law Enforcement Counter Terror Course, Level 2 – YouTube, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YTYG9wdrKfI

- Direct Action Resource Center – Tactical Urban Sustainment Course : r/preppers – Reddit, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.reddit.com/r/preppers/comments/1em0hcx/direct_action_resource_center_tactical_urban/

- Alliance Police Training | To Serve & Protect the Citizens of Alliance, Ohio, accessed January 25, 2026, https://alliancepolicetraining.com/

- Alliance, Ohio Police Training Facility – Allies in Arms – Recoil Magazine, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.recoilweb.com/alliance-ohio-police-training-facility-103847.html

- Alliance Police Training Facility – YouTube, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mpJO52gLmPk

- Presscheck’s No Fail Pistol – American Cop, accessed January 25, 2026, https://americancop.com/presschecks-no-fail-pistol/

- Centrifuge Training VCQB Instructor LE Only, accessed January 25, 2026, https://alliancepolicetraining.com/event/centrifuge-training-vcqb-instructor-le-only/

- Top 5 Firearms Instructors (That You Can Still Learn From), accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.pewpewtactical.com/top-firearms-instructors/

- Gunsite questions. : r/Firearms – Reddit, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.reddit.com/r/Firearms/comments/4blqao/gunsite_questions/

- Training – Constellis, accessed January 25, 2026, https://constellis.com/training/

- Gunsite Firearm Classes – Gunsite Academy, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.gunsite.com/classes/

- Gunsite 250 with Optics class review : r/guns – Reddit, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.reddit.com/r/guns/comments/12rlbe6/gunsite_250_with_optics_class_review/

- Pistol Classes Archives – Gunsite Academy, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.gunsite.com/class-category/pistol-classes/

- Sig Academy Handgun 102? : r/CTguns – Reddit, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.reddit.com/r/CTguns/comments/w7x8m7/sig_academy_handgun_102/

- VTAC Carbine Streetfighter – SIG SAUER Academy, accessed January 25, 2026, https://sigsaueracademy.com/courses/vtac-carbine-streetfighter-nh

- SIG SAUER Academy: Home, accessed January 25, 2026, https://sigsaueracademy.com/

- Northern Red Training : r/ar15 – Reddit, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.reddit.com/r/ar15/comments/1aqvdm4/northern_red_training/

- Government Training — Northern Red, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.northernredtraining.com/training

- Extreme CQB Training & Tactics with Northern Red – Reddit, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.reddit.com/r/CQB/comments/cq0yfa/extreme_cqb_training_tactics_with_northern_red/

- Shivworks ECQC After Action | 04-06MAY2018 | Primary & Secondary Forum, accessed January 25, 2026, https://primaryandsecondary.com/forum/index.php?threads/shivworks-ecqc-after-action-04-06may2018.4641/

- AAR: Centrifuge Training (Will Petty) “Vehicle Close Quarters Battle”, Alliance, OH 6/29-30/19 – civilian gunfighter, accessed January 25, 2026, https://civiliangunfighter.wordpress.com/2019/07/08/aar-centrifuge-training-will-petty-vehicle-close-quarters-battle-alliance-oh-6-29-30-19/

- TRAINING – Presscheck Consulting, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.presscheckconsulting.com/training

- Inside Texas SWAT Training w/ TTPOA Director Brandon Hernandez – YouTube, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Hpz19_UYn4

- Basic Special Weapons And Tactics (SWAT) Training | TEEX.ORG, accessed January 25, 2026, https://teex.org/class/let555/

- Training | NTOA, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.ntoa.org/training/

- Basic SWAT – National Tactical Officers Association – NTOA Publications, accessed January 25, 2026, https://public.ntoa.org/default.asp?action=courseview&titleid=72

- Training : r/NightVision – Reddit, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.reddit.com/r/NightVision/comments/ryhivf/training/

- Results of a 4 Year Handgun Red Dot Study by Sage Dynamics : r/CCW – Reddit, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.reddit.com/r/CCW/comments/6uixc5/results_of_a_4_year_handgun_red_dot_study_by_sage/

- International Tactical: Firearm and Tactics Training, accessed January 25, 2026, https://internationaltactical.com/

- Perfect Storm: Crossing Streams | Thunder Ranch, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.traintr.com/event-details/perfect-storm-crossing-streams-2026-09-24-08-00

- Viking Invasion: Viking Tactics Carbine 1.5 Course – SWAT Survival | Weapons, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.swatmag.com/article/viking-invasion-viking-tactics-carbine-1-5-course/

- Advanced Training | CATO, accessed January 25, 2026, https://catotraining.org/advanced-training

- Training Catalog | Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers – FLETC, accessed January 25, 2026, https://www.fletc.gov/training-catalog

- Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training: Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training, accessed January 25, 2026, https://alerrt.org/

- 88 Tactical | The Midwest’s Premier Entertainment Facility, accessed January 25, 2026, https://88tactical.com/