The Zastava M92 compact assault rifle, a weapon that entered production at the precise moment its parent nation was violently disintegrating, cannot be understood merely as a shortened Kalashnikov variant. Its existence is a direct and tangible consequence of the unique geopolitical and military-strategic environment of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY). To comprehend the M92’s design, purpose, and legacy, one must first analyze the decades of strategic thought that created the specific operational requirement it was built to fulfill. The weapon was not an imitation of a foreign trend but a bespoke solution to a long-standing Yugoslav military problem, forged by a doctrine of national survival that was unique in Cold War Europe.

Yugoslavia’s Unique Strategic Posture: The “All-People’s Defense” Doctrine

Unlike the clearly defined blocs of NATO and the Warsaw Pact, Yugoslavia under Marshal Josip Broz Tito charted a fiercely independent, non-aligned course. This strategic independence, however, came at the cost of strategic isolation. Yugoslav military planners had to prepare for a potential invasion from either the West or the East, often against a technologically and numerically superior aggressor.1 The national memory of the successful, yet brutal, partisan struggle against Axis occupation during the Second World War provided the foundational blueprint for the nation’s defense strategy.2 This experience was codified into the doctrine of “Total National Defense” or “All-People’s Defense” (Opštenarodna odbrana, or ONO).3

The core concept of ONO was to make the price of occupying Yugoslavia unacceptably high for any invader. It was a strategy of deterrence through attrition, envisioning a whole-of-society resistance where, as the doctrine stated, any citizen resisting an aggressor was considered a member of the armed forces.1 This philosophy created a unique dual-force structure. The first tier was the Yugoslav People’s Army (Jugoslovenska Narodna Armija, or JNA), a professional, conventional military force tasked with meeting an invasion with a short, sharp conventional defense. Its role was not to defeat a superpower but to blunt the initial assault, inflict heavy casualties, and buy time for the second tier to mobilize.4

The second, and arguably more critical, tier was the Territorial Defense (Teritorijalna odbrana, or TO). The TO was a massive, decentralized, partisan-style force composed of reservists and citizen-soldiers organized at the republic, municipal, and even factory level.1 Similar in concept to a national guard, each of Yugoslavia’s constituent republics maintained its own TO formations, with caches of weapons and equipment distributed locally.1 In the event of an occupation, the TO was designed to melt away into the familiar local terrain and wage a protracted guerrilla war, harassing enemy supply lines, conducting sabotage, and bleeding the occupying force dry.2 This two-tiered system, with the JNA as the “solid core” and the TO as the vast, irregular mass, was the bedrock of Yugoslav defense planning.2

This doctrine had profound implications for armament. The JNA required modern, sophisticated weapon systems for its conventional role, but the overall system demanded simplicity, ruggedness, and logistical commonality. The weapons of the TO needed to be robust, easy to maintain, and chambered in calibers that were already stockpiled in vast quantities across the country. This created an institutional preference for standardized platforms that could be used effectively by both a professional JNA soldier and a hastily mobilized TO reservist with minimal cross-training.1

The Zastava M70, chambered in the ubiquitous 7.62x39mm cartridge, was the perfect embodiment of this philosophy for the standard infantry rifle. However, as the JNA evolved, it became clear that the full-length M70 could not meet the needs of all its soldiers.

The Evolving Needs of the JNA and the “Jedinstvo” Reforms

By the mid-1980s, the JNA was undergoing a significant modernization effort under a top-secret strategic plan named “Jedinstvo” (Unity).4 Spanning from 1987 with a planned completion in 1995, the Jedinstvo reforms aimed to transform the JNA from a large, somewhat rigid force based on infantry divisions into a more modern, flexible, and hard-hitting military structured around combined-arms brigades.4 Ten of the twelve existing infantry divisions were to be converted into twenty-nine tank, mechanized, and mountain infantry brigades, each with integral artillery, air defense, and anti-tank assets.4 This shift was designed to increase operational flexibility, maneuverability, and tactical initiative, moving away from a model that risked large units being destroyed in set-piece battles.4

This doctrinal evolution created and amplified a significant capability gap in the JNA’s small arms inventory. The standard-issue Zastava M70, while an excellent and robust assault rifle, was too long and unwieldy for the increasingly specialized roles within these new brigade structures. Several key units were particularly affected:

- Armored and Mechanized Vehicle Crews: The JNA’s mechanized brigades were built around infantry fighting vehicles like the domestically produced BVP M-80.9 The crews of these vehicles—drivers, gunners, and commanders—required a compact personal defense weapon for self-defense in the event of a bailout and for operating in the cramped confines of their vehicles. A full-length M70 was simply impractical. The need for a compact, rifle-caliber weapon for vehicle crews was a recognized issue in armies worldwide, and Yugoslavia was no exception.11

- Airborne Forces: The JNA’s premier special operations unit was the 63rd Parachute Brigade, based in Niš.12 As an elite airborne force, its primary mission involved vertical envelopment, reconnaissance, and sabotage deep in the enemy’s rear.12 For these soldiers, a compact, lightweight weapon with a folding stock was not a luxury but an operational necessity. The standard M70, particularly the fixed-stock M70B1, was ill-suited for parachute operations. Definitive evidence of this long-standing requirement gap is the fact that the 63rd Parachute Brigade continued to use WWII-era German Sturmgewehr 44 (StG 44) assault rifles for training and potentially as a reserve weapon well into the 1980s.13 While some of this may have been for distinctiveness or to save wear on primary rifles during training, the StG 44’s continued presence points to a clear and unfulfilled need for a modern, intermediate-caliber compact assault rifle that did not yet exist in the JNA’s arsenal.13

- Special Forces and Security Units: Mirroring global trends in the 1970s and 1980s, the JNA and Yugoslav security services developed specialized counter-terrorist and special operations units, such as the precursor to the modern “Cobras”.16 These units required weapons optimized for Close Quarters Battle (CQB), where a shorter barrel and overall length provide a decisive advantage in maneuverability inside buildings, aircraft, and vehicles.11

The “Jedinstvo” reforms, by creating more of these specialized units and emphasizing mobility and maneuver, brought this capability gap into sharp focus. The JNA needed a domestic equivalent to the types of compact carbines that were becoming increasingly prevalent in other modern armies.

The Global Context: The Rise of the Compact Carbine and PDW

The JNA’s search for a compact assault rifle did not occur in a strategic vacuum. The 1970s and 1980s saw a global trend towards shortening the standard infantry rifle to create more specialized carbine variants. This trend was driven by the changing nature of warfare, which increasingly involved mechanized infantry, urban combat, and special operations.

The most direct conceptual parallel to the future M92 was the Soviet AKS-74U, colloquially known as the “Krinkov.” Developed in the late 1970s, the AKS-74U was a drastically shortened version of the AK-74, designed specifically for vehicle crews, artillerymen, and Spetsnaz special forces who needed more firepower than a pistol but could not be encumbered by a full-length rifle.17 Its development established a clear precedent within the Warsaw Pact for a rifle-caliber sub-compact weapon.

Simultaneously, in the United States, the experiences of the Vietnam War and the needs of special operations forces led to the development of carbine versions of the M16, starting with the CAR-15 family and culminating in the M4 Carbine program in the 1980s.19 The U.S. military recognized that for many soldiers, particularly those operating in and out of vehicles or in close quarters, a shorter, handier weapon was more effective than a long infantry rifle.19

This era also saw the birth of the Personal Defense Weapon (PDW) concept, formalized by a NATO request in the late 1980s.20 The goal was to develop a new class of firearm for rear-echelon and support troops that was compact like a submachine gun but could defeat Soviet body armor, a capability standard pistol-caliber submachine guns lacked.22 This effort would eventually lead to weapons like the FN P90 and H&K MP7.21

While the Yugoslavs were undoubtedly aware of these international developments, their motivation for creating the M92 was primarily rooted in their own established doctrine. The need for a compact weapon for paratroopers, vehicle crews, and special forces was a direct result of the “All-People’s Defense” concept and the JNA’s “Jedinstvo” modernization. The global trend simply confirmed the validity of their requirement and provided conceptual models, like the AKS-74U, for a potential solution. The development of the Zastava M92 was Yugoslavia’s indigenous, pragmatic answer to a question that modern militaries around the world were asking at the same time.

Engineering and Evolution: The Path to the M92

The Zastava M92 was not a revolutionary design created from a blank slate. Instead, it was the culmination of an evolutionary process, a logical and pragmatic adaptation of Zastava Arms’ existing, well-proven Kalashnikov-pattern rifle family. Its development history reveals a characteristically Yugoslav approach to arms manufacturing: leveraging a robust domestic design base, prioritizing logistical simplicity, and making deliberate engineering choices based on ballistic realities. The path to the M92 began with its full-sized progenitor, the M70, and took a crucial detour through a NATO-caliber variant before arriving at its final, domestically-optimized form.

The Foundation: The Zastava M70 Family

The bedrock of Yugoslav small arms production from 1970 onward was the Zastava M70 assault rifle.24 While externally resembling the Soviet AKM, the M70 was not a licensed copy. Due to the political split between Tito and Stalin in 1948, Yugoslavia was outside the Soviet sphere of influence and did not receive technical data packages for Soviet weaponry.24 Zastava’s engineers developed the M70 by reverse-engineering early pattern, milled-receiver AK-47s that had been acquired covertly.24 This independent development process resulted in a rifle with several distinct features that set it apart from its Warsaw Pact counterparts and established a unique “Yugo” design philosophy.

Key among these features was an emphasis on ruggedness and multi-functionality. Later stamped-receiver versions of the M70, such as the M70B1, utilized a receiver made from 1.5mm thick steel, compared to the standard 1.0mm receiver of the Soviet AKM.26 This was complemented by the use of a bulged front trunnion, similar to that found on the RPK light machine gun, which provided a more robust lockup for the barrel and enhanced the weapon’s overall durability.24 This “overbuilt” construction was a hallmark of Zastava’s military rifles, designed to withstand the rigors of sustained combat and, crucially, the stress of launching rifle grenades.26

The M70’s integrated rifle grenade capability was its most unique feature. It included a flip-up ladder sight mounted on the gas block. When raised into the firing position, the sight arm also functioned as a gas cut-off, blocking the gas port to prevent the action from cycling when firing a grenade.24 This allowed the rifle to safely project anti-personnel and anti-tank grenades without a separate launcher, a capability deeply aligned with the self-sufficient, partisan-style warfare envisioned by the ONO doctrine. Other distinctive features included a non-chrome-lined, cold-hammer-forged barrel, which some analysts suggest may offer a slight accuracy advantage over chrome-lined barrels at the cost of requiring more diligent cleaning, and proprietary magazines with a follower that held the bolt open after the last round was fired.24 This family of robust, multi-functional rifles, with its emphasis on durability, formed the engineering and manufacturing foundation from which the M92 would spring.

The M85 Carbine: A Flirtation with 5.56mm

Before the M92 was finalized, Zastava first developed its direct predecessor: the M85 carbine.15 The M85 is, for all practical purposes, an M92 chambered for the 5.56x45mm NATO cartridge.28 It shares the same compact layout, 10-inch barrel, underfolding stock, and distinctive three-vent handguard.28 The development of a NATO-caliber carbine first might seem counterintuitive for a military that exclusively used Warsaw Pact-style ammunition, but it reveals a key aspect of Yugoslavia’s strategy: arms exports.

As a non-aligned nation, Yugoslavia was not restricted to supplying only one side of the Cold War. Zastava Arms actively sought to export its products to a global market to generate hard currency for the state.30 The 5.56x45mm cartridge was the standard for NATO and a popular choice for many non-aligned nations worldwide. Developing the M85 provided Zastava with a modern, compact carbine that was highly attractive on the international arms market.28 It was an outward-facing product, designed for geopolitical and commercial flexibility. This development also gave Zastava’s engineers valuable experience in adapting the Kalashnikov operating system to a smaller, higher-pressure cartridge, and it provided the JNA with a potential pathway to NATO ammunition interoperability should the strategic situation ever demand it. The M85 was thus a logical first step, establishing the core design of the compact carbine platform while targeting the lucrative export market.

The M92: A Pragmatic Return to 7.62x39mm

While the M85 was a sensible export product, it was a logistical non-starter for domestic use by the JNA. The Yugoslav military’s entire small arms ecosystem—from ammunition factories in places like Igman to the vast, distributed stockpiles for the TO—was built around the 7.62x39mm M43 cartridge.25 Introducing a new caliber, 5.56x45mm, solely for specialized units would have created an immense and unnecessary logistical burden. It would have required separate supply chains, separate magazines, and separate training, all of which ran counter to the ONO doctrine’s emphasis on simplicity and interoperability between JNA and TO forces.

Furthermore, as will be explored in the next section, there were compelling ballistic reasons to prefer the $7.62x39mm round for a short-barreled weapon. The cartridge’s design allows it to retain a significantly higher percentage of its velocity and energy when fired from a short barrel compared to high-velocity small-caliber rounds.11 For the intended role of a compact carbine with an effective range of 200-400 meters, the older cartridge was, in fact, the technically superior choice.

Consequently, Zastava adapted the existing M85 design to the JNA’s standard rifle cartridge, creating the M92. Development and testing were completed, and batch production began in 1992.11 The M92 was the final, pragmatic synthesis of this development process. It combined the compact form factor inspired by global trends and pioneered in the M85 with the robust, overbuilt mechanics of the M70 family, all chambered in the JNA’s logistically sound and ballistically optimal cartridge. This dual-track development of the M85 for export and the M92 for domestic use demonstrates the efficiency of a state-run arms industry. Zastava designed the platform once and then chambered it for two distinct strategic purposes, maximizing their engineering investment while perfectly tailoring the final products to their intended end-users.

Technical and Ballistic Analysis

A detailed technical examination of the Zastava M92 reveals a weapon that is more than a simple copy of the Soviet AKS-74U. It is a distinct design that reflects a different set of engineering priorities, heavily influenced by the manufacturing traditions of Zastava Arms and the specific performance requirements of the JNA. The M92’s features, particularly its sighting system and its choice of caliber, represent deliberate improvements and pragmatic choices that distinguish it from its conceptual counterparts and contribute to its reputation for robustness and effectiveness.

Zastava M92: A Detailed Examination

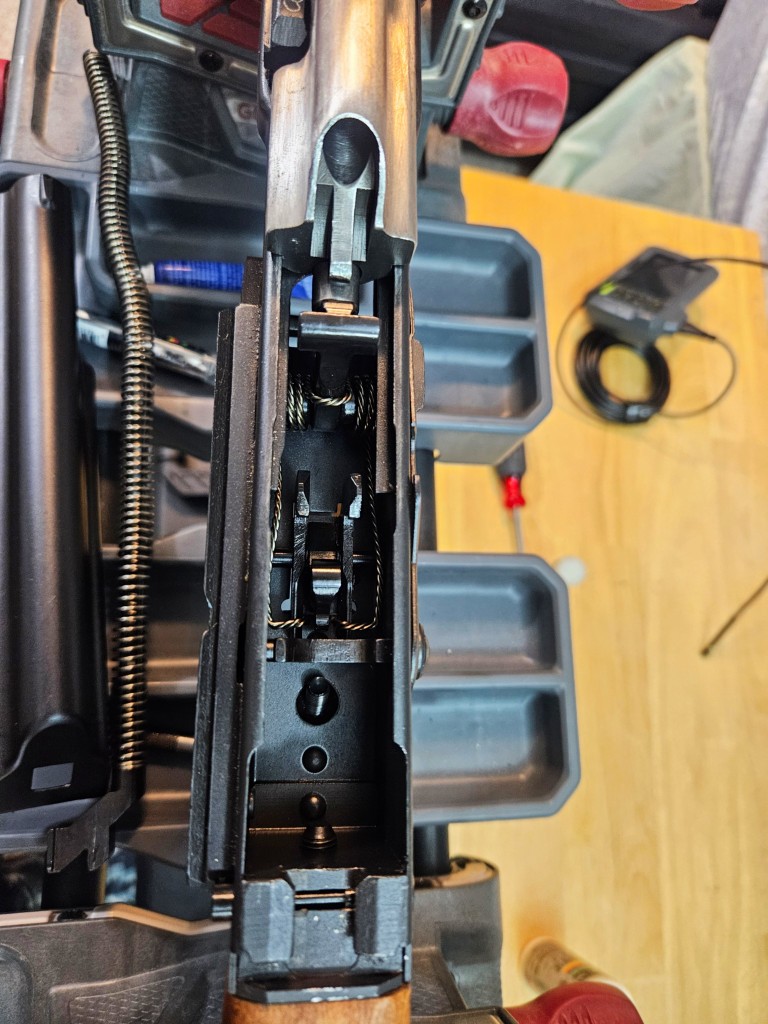

The Zastava M92 is a gas-operated, selective-fire carbine utilizing the long-stroke piston and rotating bolt action of the Kalashnikov family.11 While it shares this fundamental operating principle, several of its components and design features are uniquely Yugoslav.

- Receiver and Trunnion: The original military-issue M92 carbines were built on a stamped receiver derived from the standard Zastava M70, typically using 1.0mm sheet steel. This differs from the later civilian export models (ZPAP92) which often feature the heavier 1.5mm receiver and bulged RPK-style front trunnion that have become a trademark of modern Zastava AKs.26 Even without the heavier construction of the civilian models, the military M92 was built to Zastava’s high standards of durability.

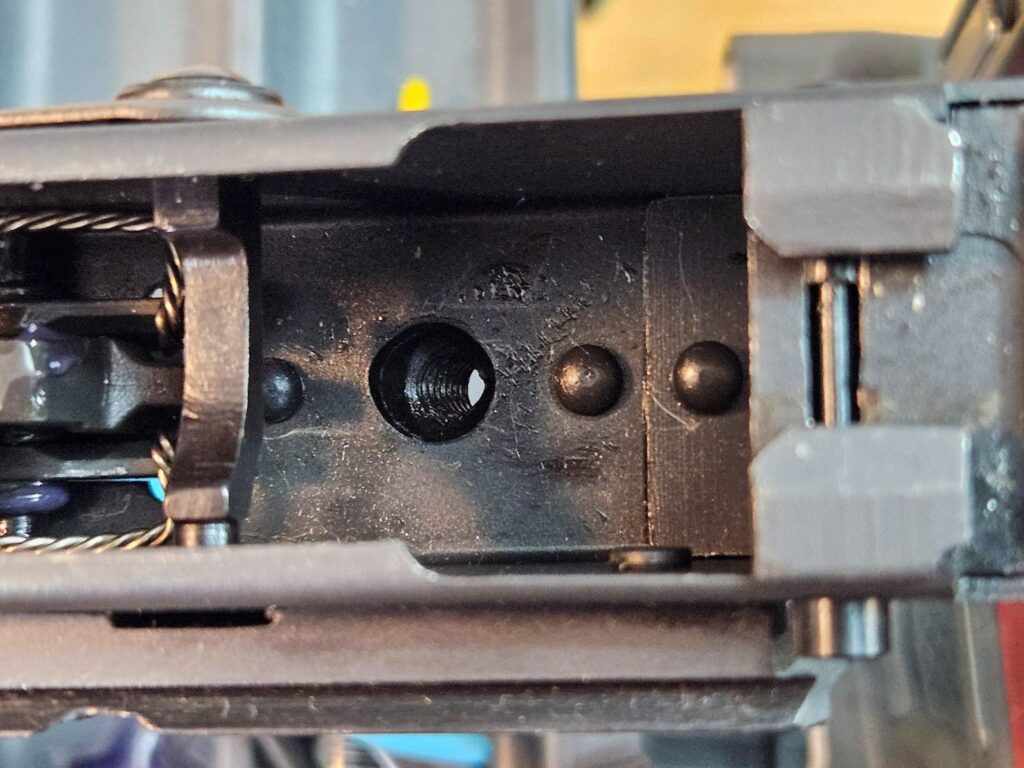

- Hinged Dust Cover and Sights: Perhaps the most significant design departure from the Soviet AKS-74U is the M92’s sighting system. The rear sight is not located on the rear sight block in the traditional Kalashnikov position. Instead, it is mounted on the rear of the dust cover.37 To make this viable, the M92 employs a sturdy hinged dust cover that locks securely to the rear sight block, providing a stable platform that is capable of retaining zero.36 This design accomplishes two things: it moves the rear aperture closer to the shooter’s eye for a more intuitive sight picture, and it dramatically increases the sight radius compared to the AKS-74U. A longer sight radius inherently allows for greater practical accuracy. The sight itself is a simple, robust L-shaped flip sight with two apertures, typically set for 200 and 400 meters.38 Many military versions were also fitted with flip-up tritium inserts for low-light aiming.

- Handguard: The M92 features the longer, three-vent wooden handguard that is a signature of the Zastava M70 family.11 This provides the user with more surface area for a secure grip compared to the very short handguard of the AKS-74U and is believed to offer superior heat dissipation during sustained automatic fire.40

- Muzzle Device: The barrel is capped with a distinctive conical muzzle device. This device functions both as a flash hider, reducing the significant muzzle flash from the short barrel, and as a gas booster.39 By trapping a portion of the expanding gases at the muzzle, it creates a small expansion chamber that increases the pressure acting on the gas piston, ensuring reliable cycling of the action despite the short dwell time of the 10-inch barrel.

- Stock: The M92 utilizes the same robust and proven underfolding steel stock found on the M70AB2 variant of the standard assault rifle.11 While perhaps less comfortable than some side-folding designs, it is exceptionally durable and creates a very compact package when folded.

| Feature | Specification | Source(s) |

| Caliber | 7.62x39mm | 11 |

| Action | Gas-operated, long-stroke piston, rotating bolt | 11 |

| Mass | 3.57 kg (with empty magazine) | 11 |

| Length (Extended) | 795 mm | 11 |

| Length (Folded) | 550 mm | 11 |

| Barrel Length | 254 mm (10.0 in) | 11 |

| Rate of Fire (Cyclic) | 620 rounds/min | 11 |

| Muzzle Velocity | 678 m/s | 11 |

| Effective Range | 200 – 400 m | 11 |

| Feed System | Standard AK-pattern 30-round box magazines; also compatible with 5, 10, 40-round box and 75, 100-round drum magazines | 11 |

| Sights | Hinged top cover with flip-up rear aperture (200/400m), post front sight | 39 |

Comparative Analysis: M92 vs. AKS-74U

When placed alongside its Soviet conceptual equivalent, the AKS-74U, the differing design philosophies of the Yugoslav and Soviet arms industries become apparent. While both weapons were created to fill the same tactical niche, they arrived at different solutions with distinct trade-offs. The M92 prioritizes shooter ergonomics and practical accuracy, while the AKS-74U prioritizes absolute compactness and light weight.

The most fundamental difference is the caliber. The M92’s use of 7.62x39mm results in a heavier weapon with more felt recoil, but it offers superior performance from a short barrel, as will be discussed below. The AKS-74U’s 5.45x39mm round provides a flatter trajectory and lighter recoil, but its effectiveness is more sensitive to velocity loss from its short barrel.17

The sighting systems represent a major philosophical divergence. The M92’s hinged top cover and rear-mounted sight provide a sight radius of approximately 14 inches, comparable to some full-size rifles. The AKS-74U, with its rear sight in the standard position, has a sight radius of only about 9.5 inches. This nearly 50% increase in sight radius gives the M92 a significant advantage in potential precision.

Ergonomically, the M92’s longer handguard offers a more comfortable and stable grip for the support hand, while the AKS-74U’s extremely short handguard can be awkward for many shooters. The M92’s underfolding stock is famously durable, whereas the AKS-74U’s triangular side-folder is lighter and arguably more comfortable against the shoulder. These differences illustrate that Yugoslav engineers were willing to accept a slight increase in weight and folded length to deliver a weapon that was more user-friendly and arguably more effective as a fighting tool.

| Feature | Zastava M92 | Kalashnikov AKS-74U |

| Caliber | 7.62x39mm | 5.45x39mm |

| Muzzle Velocity | 678 m/s | 735 m/s |

| Barrel Length | 254 mm (10.0 in) | 210 mm (8.3 in) |

| Length (Extended) | 795 mm | 735 mm |

| Length (Folded) | 550 mm | 490 mm |

| Weight (Empty) | 3.2 kg | 2.5 kg |

| Sighting System | Hinged top cover, flip-up rear | Standard rear sight block, flip-up rear |

| Stock Type | Underfolding, steel | Side-folding, steel (triangular) |

| Handguard Design | Long, 3-vent wood | Short, 2-vent wood |

The Caliber Question: The Merits of 7.62x39mm in a Short Barrel

The decision to chamber the M92 in 7.62x39mm was not merely one of logistical convenience; it was a sound ballistic choice. The performance of a rifle cartridge is directly related to barrel length, but not all cartridges are affected equally. High-velocity, small-caliber (SCHV) rounds like 5.56x45mm NATO and 5.45x39mm depend on high velocity for their terminal effectiveness, which is primarily achieved through the fragmentation or rapid yawing of the projectile upon impact.43 This effect is highly velocity-dependent. When fired from a very short barrel, these rounds suffer a significant loss in velocity, which can drop them below the threshold required for reliable fragmentation or yaw, drastically reducing their lethality.45

The 7.62x39mm cartridge, by contrast, is ballistically more efficient in shorter barrels.11 It uses a heavier projectile at a more moderate velocity, and its powder is designed to burn effectively in a shorter length. While it does lose velocity when moving from a 16-inch barrel to a 10-inch barrel, the percentage of loss is less dramatic, and its terminal effectiveness is less dependent on achieving a specific velocity threshold.45 The M92’s muzzle velocity of approximately 678 m/s is only about 10% less than the 735 m/s of a full-length M70, a negligible difference at the carbine’s intended engagement ranges.11

Furthermore, the heavier 7.62mm projectile retains more kinetic energy at close to medium ranges and offers substantially better performance against intermediate barriers.42 In the urban and complex terrain where a compact carbine is most likely to be used, the ability to effectively penetrate car doors, wooden structures, and masonry is a significant tactical advantage.33 Tests have shown that the M92’s 7.62x39mm round penetrates barriers like cinder blocks much more effectively than the 5.45x39mm round from an AKS-74U.47 Therefore, for the specific roles envisioned for the M92—arming paratroopers, vehicle crews, and special forces operating in potentially dense environments—the choice of the 7.62x39mm cartridge was not a compromise but an optimization, providing reliable terminal performance and superior barrier penetration in a compact platform.

Operational History and Assessment of Success

The success of a military firearm can be measured by several metrics: its effectiveness in fulfilling its intended doctrinal role, its longevity in service, its commercial success on the export market, and its enduring reputation. By these measures, the Zastava M92 has proven to be a resounding, albeit paradoxical, success. It was a weapon designed for a specific army and a specific national defense scenario that ceased to exist almost at the moment of its birth. Yet, the M92’s inherent qualities allowed it to thrive in the brutal conflict that followed its introduction, become a valuable export for the Serbian state, and achieve an iconic status in the world’s largest civilian firearms market.

Trial by Fire: The M92 in the Yugoslav Wars

The Zastava M92 entered batch production in 1992, a year after the outbreak of the Yugoslav Wars.11 This timing is critical to understanding its operational history. The M92 was never fielded by the unified, multi-ethnic JNA for which it was designed. Instead, its first combat use was with the successor armies that emerged from the JNA’s dissolution, most notably the armed forces of the new Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) and the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) in Bosnia.40

Despite this chaotic introduction, the M92 was issued precisely to the types of units for which it was originally intended: special forces, airborne units, military police, and the crews of armored vehicles.11 The nature of the Yugoslav Wars, characterized by brutal urban combat, ambushes in complex terrain, and close-quarters fighting, created an environment where the M92’s attributes were highly valued. Its compact size and folding stock made it far more maneuverable inside buildings and vehicles than the full-length M70.40 The potent 7.62x39mm cartridge provided excellent firepower and the ability to penetrate the light cover—walls, vehicles, and barricades—that defined these engagements.33

While detailed, official after-action reports from the conflict are not readily available in open-source materials, anecdotal accounts from veterans and the weapon’s continued use by all sides attest to its effectiveness.49 The M92 was built on the legendarily reliable Kalashnikov action and manufactured to Zastava’s robust standards, ensuring it functioned dependably in the harsh conditions of the war.49 In this sense, the M92 was a tactical success. It effectively filled the doctrinal niche for a compact carbine and proved to be a formidable weapon in the very types of close-range, high-intensity conflicts it was designed for, even if the conflict itself was a civil war rather than the national defense scenario originally envisioned.

A Global Footprint: Export and Proliferation

In the aftermath of the Yugoslav Wars, the Zastava Arms factory, a cornerstone of the Serbian defense industry, resumed its role as a major global arms exporter.34 The M92 carbine, having been proven in combat, became a key product in its portfolio. Its appeal was straightforward: it was a robust, reliable, and relatively inexpensive compact assault rifle chambered in one of the most common and widely available military cartridges in the world.

The M92 has been officially exported to numerous countries, finding favor with military and security forces, particularly in the Middle East and Africa.39 Notable state users include Iraq, which also produced copies under license, Jordan, North Macedonia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.11 One of the largest single export deals was a sale of 80,000 M92 carbines to Libya in the 2008-2009 timeframe, prior to the country’s civil war.11 The production numbers are substantial, with well over 100,000 units manufactured since 1992, making it a significant commercial success for Zastava.39

However, this success has a darker side. The immense quantity of weapons present in the former Yugoslavia at the end of the wars, including countless M70s and M92s, fueled a thriving black market.52 These military-grade weapons flowed out of the Balkans and into the hands of organized crime groups and terrorist cells across Europe. Tragically, Zastava rifles originating from these stockpiles were used in the horrific 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, including the attack on the Charlie Hebdo offices and the Bataclan theatre massacre.52 This illicit proliferation, while not a reflection on the weapon’s design, is an undeniable part of its complex legacy.

The American Enthusiast: The ZPAP92’s Civilian Legacy

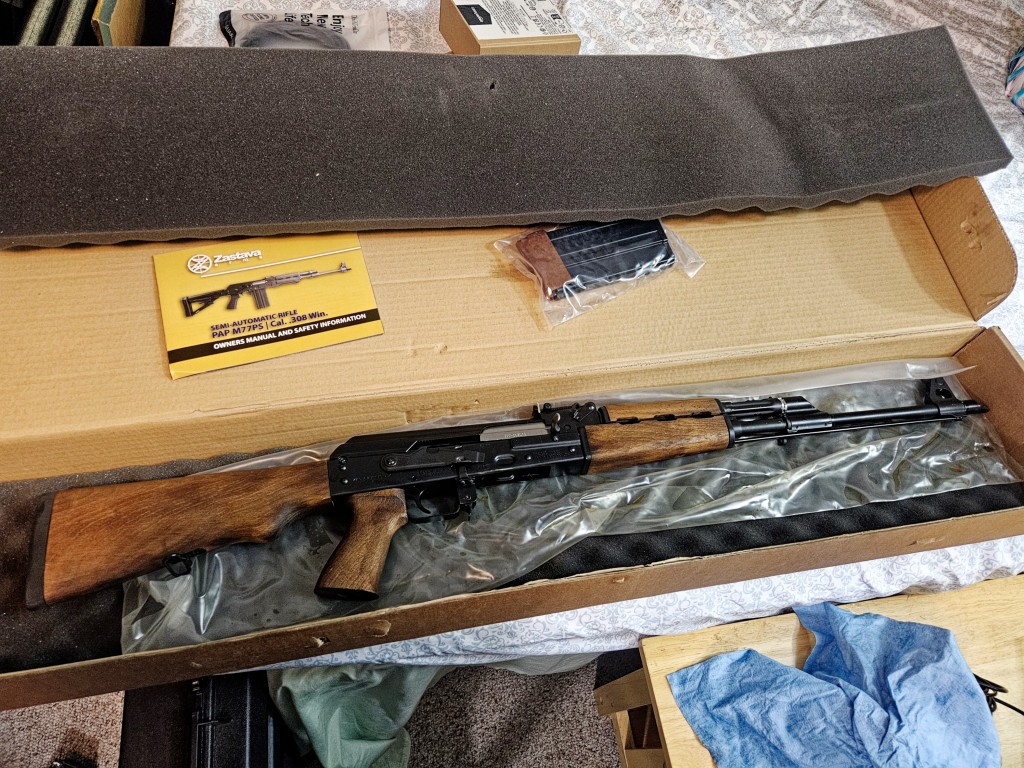

Perhaps the most remarkable chapter in the M92’s history is its second life in the United States civilian market. To comply with U.S. firearms laws, which regulate barrel length and forbid the importation of certain semi-automatic rifles, the M92 was imported as a “pistol” variant, lacking a shoulder stock.36 Initially brought in by importers like Century Arms under the name “PAP M92,” the platform later became a flagship product for Zastava Arms USA, the company’s own American subsidiary, under the “ZPAP92” designation.30

The ZPAP92 quickly earned an exceptional reputation among American firearms enthusiasts, collectors, and shooters.35 It is widely praised for its high-quality construction, durability, and reliability—attributes directly inherited from its military-grade origins.26 Civilian reviewers consistently note the “overbuilt” nature of the modern ZPAP92, which often includes the heavy-duty 1.5mm receiver and bulged RPK trunnion, making it one of the most robust AK-pattern firearms available on the market.26

Its configuration as a pistol has made it an extremely popular host for conversion into a legal Short-Barreled Rifle (SBR) through the addition of a stock, a process regulated by the National Firearms Act.50 This allows civilian owners to create a firearm that closely replicates the handling and performance of the original military M92 carbine. The platform’s reliability, robust build, and authentic military heritage have made the ZPAP92 a perennial favorite and a benchmark for quality in the imported AK market.56

Final Verdict: A Multi-Faceted Success

Assessing the Zastava M92 requires a nuanced perspective.

- Military Success: From a purely tactical and doctrinal standpoint, the M92 was a success. It successfully addressed a clear capability gap within the JNA’s force structure, providing a powerful and compact weapon for specialized units. It performed reliably and effectively in the brutal conflicts in which it was used, validating its core design principles. However, its strategic purpose—to help defend a unified Yugoslavia—was rendered moot by history.

- Commercial Success: As an export product, the M92 has been an undeniable success for Zastava and the Serbian state. It has been sold in large quantities to state actors around the world and remains in production decades after its introduction, a testament to the enduring appeal of its design.34

- Civilian Success: In the highly competitive U.S. civilian market, the semi-automatic ZPAP92 is not just successful; it is an icon. It is regarded as one of the highest-quality and most desirable AK-pattern firearms available, cementing the M92’s legacy far beyond its Balkan origins.56

The M92’s journey is a paradox. It was a weapon conceived for a country that vanished as it was being born. Its greatest legacy was not in the defense of that nation, but in its performance during the nation’s violent demise, and more profoundly, in its subsequent, long-lasting career as a sought-after commodity on both state-sponsored and civilian arms markets.

Conclusion: The M92 as a Symbol of Yugoslav Pragmatism

The Zastava M92 carbine stands as a powerful testament to the unique military-industrial philosophy of the former Yugoslavia. It is a weapon born not of imitation, but of a deeply considered and long-standing doctrinal need. Its development was a direct response to the requirements of the “Total National Defense” strategy and the late-stage modernization of the Yugoslav People’s Army, which demanded a compact yet powerful firearm for its increasingly specialized mechanized, airborne, and special forces units. The anachronistic use of German StG 44s by elite paratroopers into the 1980s serves as the most compelling evidence of this long-unfilled capability gap.

The engineering path to the M92 showcases a remarkable pragmatism. Zastava’s engineers did not reinvent the wheel; they refined and adapted their existing, combat-proven M70 platform. The decision to chamber the domestic-use M92 in 7.62x39mm, despite having already developed the 5.56x45mm M85 for export, was a masterstroke of logistical and ballistic reasoning. It maintained absolute ammunition commonality within the Yugoslav armed forces, a critical consideration for a doctrine reliant on a mobilized citizenry, while simultaneously leveraging the superior performance of the 7.62x39mm cartridge in a short-barreled platform. Design choices, such as the robust hinged top cover that allowed for a longer sight radius, demonstrate a clear focus on creating a more practical and effective fighting weapon, even at the cost of slightly more weight and size compared to its Soviet counterpart.

The M92’s legacy is one of ironic and multifaceted success. Conceived to defend a unified nation, it was instead baptized in the fires of that nation’s collapse, where it proved its tactical worth in the brutal close-quarters combat of the Yugoslav Wars. In the decades since, the carbine’s inherent qualities of ruggedness, reliability, and potent firepower have made it a highly successful export for the Serbian defense industry and, most remarkably, an esteemed icon in the American civilian firearms market. It has outlived the country, the army, and the doctrine that created it. The Zastava M92 is, therefore, more than just a shortened AK. It is a symbol of Yugoslav independence and pragmatism, a thoughtfully designed tool of war whose robust construction and sound engineering have earned it a deserved and enduring place as one of the most effective compact Kalashnikov-pattern carbines ever produced.

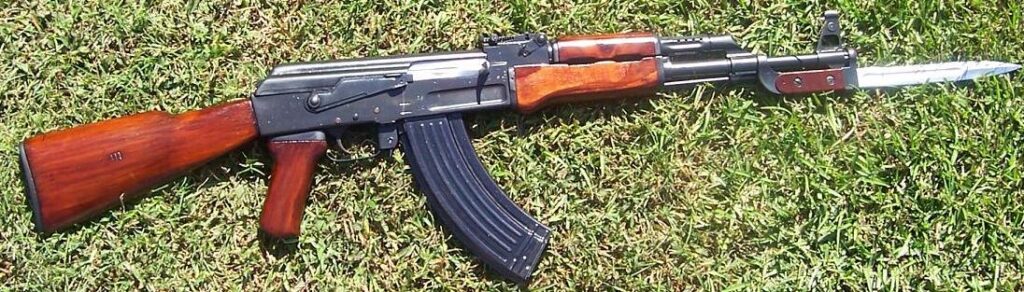

Image Source

The main blog photo of a M92 was obtained from Wikimedia on October 12, 2025. The original photo was taken by Srđan Popović in 2015.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- Territorial Defense (Yugoslavia) – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Territorial_Defense_(Yugoslavia)

- The Yugoslav People’s Army: Its Military and Political Mission – DTIC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA092586.pdf

- THE YUGOSLAV CONCEPT OF “ALL-NATIONAL DEFENSE”, accessed August 4, 2025, http://www.icwa.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/DR-50.pdf

- Yugoslav People’s Army – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yugoslav_People%27s_Army

- (EST PUB DATE) YUGOSLAVIA: MILITARY DYNAMICS OF A … – CIA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/DOC_0000372340.pdf

- COMBATANT FORCES IN THE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA – CIA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/DOC_0005621706.pdf

- The Yugoslav People’s Army: Its Military and Political Mission – DTIC, accessed August 4, 2025, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA092586

- Slovenian Territorial Defense in the Ten-Day War – Scientific Journal of the Military University of Land Forces, accessed August 4, 2025, https://zeszyty-naukowe.awl.edu.pl/article/01.3001.0015.3411/en

- Yugoslavia’s BVP M-80 Infantry Fighting Vehicle Explained | SOVIET BMP COUSIN, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lDV0PobvIQA

- Yugoslav Ground Forces – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yugoslav_Ground_Forces

- Zastava M92 – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zastava_M92

- 63. padobranska brigada | Vojska Srbije, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.vs.rs/sr_lat/jedinice/vojska-srbije/63padobranska-brigada

- Yugoslav paratroopers with STG-44s during the 1980s, they were the last modern military with the gun widely in use. – Reddit, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/ForgottenWeapons/comments/q5iv36/yugoslav_paratroopers_with_stg44s_during_the/

- I love the 70s/80s Yugoslav paratrooper look. Weird Combloc gear and S… – TikTok, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.tiktok.com/@americana.pipedream/video/7140697909997112619

- Jugoslav Army Weapons – Small Arms Review, accessed August 4, 2025, https://smallarmsreview.com/jugoslav-army-weapons/

- Положај и делатност специјалних безбедносних јединица Републике Србије – prafak, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.prafak.ni.ac.rs/files/master/ZMR_StefanMacicM007_22_UP.pdf

- Kalashnikov AKS-74U – Weaponsystems.net, accessed August 4, 2025, https://weaponsystems.net/system/680-Kalashnikov+AKS-74U

- Personal Defense Weapons, accessed August 4, 2025, https://sadefensejournal.com/personal-defense-weapons/

- M4 carbine – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M4_carbine

- THE PDW CONCEPT APPLIED TO CCW PISTOLS – GABE SUAREZ BLOG – TypePad, accessed August 4, 2025, https://warriortalknews.typepad.com/the-gabe-suarez-blog/2016/02/the-pdw-concept-applied-to-ccw-pistols.html

- Heckler & Koch MP7 – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heckler_%26_Koch_MP7

- PDWs: A revolution that never quite happened – European Security & Defence, accessed August 4, 2025, https://euro-sd.com/2025/02/articles/42600/pdws-a-revolution-that-never-quite-happened/

- Personal defense weapon – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Personal_defense_weapon

- Zastava M70 assault rifle – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zastava_M70_assault_rifle

- What weapons were used in the Yugoslav War? – Quora, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.quora.com/What-weapons-were-used-in-the-Yugoslav-War

- In your opinion, is the Zavasta M70 (AK) a good rifle? How would you rate its accuracy, reliability, and over all quality? Is it better than other AK’s in the same price range (PSAK, Century Arms, etc.)? – Quora, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.quora.com/In-your-opinion-is-the-Zavasta-M70-AK-a-good-rifle-How-would-you-rate-its-accuracy-reliability-and-over-all-quality-Is-it-better-than-other-AK-s-in-the-same-price-range-PSAK-Century-Arms-etc

- What’s your opinion on the M70 Zastava rifle? – Quora, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.quora.com/Whats-your-opinion-on-the-M70-Zastava-rifle

- Zastava M85 – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zastava_M85

- en.wikipedia.org, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zastava_M92#:~:text=The%20M92%20is%20a%20carbine,and%2C%20correspondingly%2C%20magazine%20design.

- History – Zastava Arms USA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://zastavaarmsusa.com/history/

- About us – Zastava oružje ad, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.zastava-arms.rs/en/about-us/

- Обзор МПК Застава М92 7.62х39мм / SEMI Zastava M92 7.62x39mm Review – YouTube, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xjDj89GvgkY

- The King Of Intermediate Cartridges: 7.62x39mm – Gun Digest, accessed August 4, 2025, https://gundigest.com/gear-ammo/ammunition/ammo-brief-7-62×39

- Zastava Arms – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zastava_Arms

- M92 PAP AK Pistol Review | Day At The Range, accessed August 4, 2025, https://dayattherange.com/m92-pap-ak-pistol-review/

- Zastava ZPAP92: The Serbian Krinkov – Gun Digest, accessed August 4, 2025, https://gundigest.com/gun-reviews/military-firearms-reviews/zastava-zpap92-the-serbian-krinkov

- Zastava M85 AK Pistol – Precise Shooter, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.preciseshooter.com/blog/M85.aspx

- Century Arms Zastava PAP M92 PV Review – International Sportsman, accessed August 4, 2025, https://internationalsportsman.com/century-arms-zastava-pap-m92-pv-review/

- Zastava M92 – Weaponsystems.net, accessed August 4, 2025, https://weaponsystems.net/system/375-Zastava+M92

- Zastava M92 – Wikiwand, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Zastava_M92

- Zastava M92 – AmmoTerra, accessed August 4, 2025, https://ammoterra.com/product/zastava-m92-1

- What round is better, 5.45×39 or 7.62×39? – Quora, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.quora.com/What-round-is-better-5-45×39-or-7-62×39

- 5 Reasons Why 7.62x39mm Beats 5.45x39mm – Firearms News, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.firearmsnews.com/editorial/5-reasons-why-762x39mm-beats-545x39mm/376952

- Reloading Press: 5.45x39mm – Gaming Ballistic, accessed August 4, 2025, https://gamingballistic.com/2016/03/07/reloading-press-545×39/

- Gen 1 8” 7.62×39 vs Gen 2 13” 5.45×39? : r/Galil – Reddit, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/Galil/comments/zvopx3/gen_1_8_762x39_vs_gen_2_13_545x39/

- 5.56 vs 7.62: A Comparison | American Firearms, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.americanfirearms.org/5-56-vs-7-62-a-comparison/

- AKS-74U vs.Yugo M92 – Block Penetration – YouTube, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IMXDRix2KKM

- Army of Republika Srpska – Wikipedia, accessed August 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Army_of_Republika_Srpska

- What is the most reliable weapon you have used during the Yugoslav Wars? – Quora, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.quora.com/What-is-the-most-reliable-weapon-you-have-used-during-the-Yugoslav-Wars

- Zastava ZPAP92 Review [Extended use AAR] – Gun University, accessed August 4, 2025, https://gununiversity.com/zastava-zpap92-review/

- Zastava M92 | Weaponsystems.net, accessed August 4, 2025, https://development.weaponsystems.net/system/375-Zastava%20M92

- How Yugoslavia’s Military-Grade Weapons Haunt Western Europe – The Defense Post, accessed August 4, 2025, https://thedefensepost.com/2020/07/30/weapons-yugoslavia-europe/

- Yugoslavian Serbia AK-47 History – Zastava – Faktory 47, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.faktory47.com/blogs/kalashnikov/yugoslavian-serbia-ak-history

- ZPAP92: 7.62×39 AK Pistol Review – Sniper Country, accessed August 4, 2025, https://snipercountry.com/zastava-pap-m92-review/

- Century Arms PAP M92: A Range Review – The Mag Life – GunMag Warehouse, accessed August 4, 2025, https://gunmagwarehouse.com/blog/century-arms-pap-m92-a-range-review/

- 2025 Market Forecast: Demand for Eastern European AKs in America – Zastava Arms USA, accessed August 4, 2025, https://zastavaarmsusa.com/2025-market-forecast-demand-for-eastern-european-aks-in-america/

- M92 PAP: You Must Own One – YouTube, accessed August 4, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LmRD_34AOLE