Reporting Period: January 17, 2026 – January 24, 2026

Executive Summary

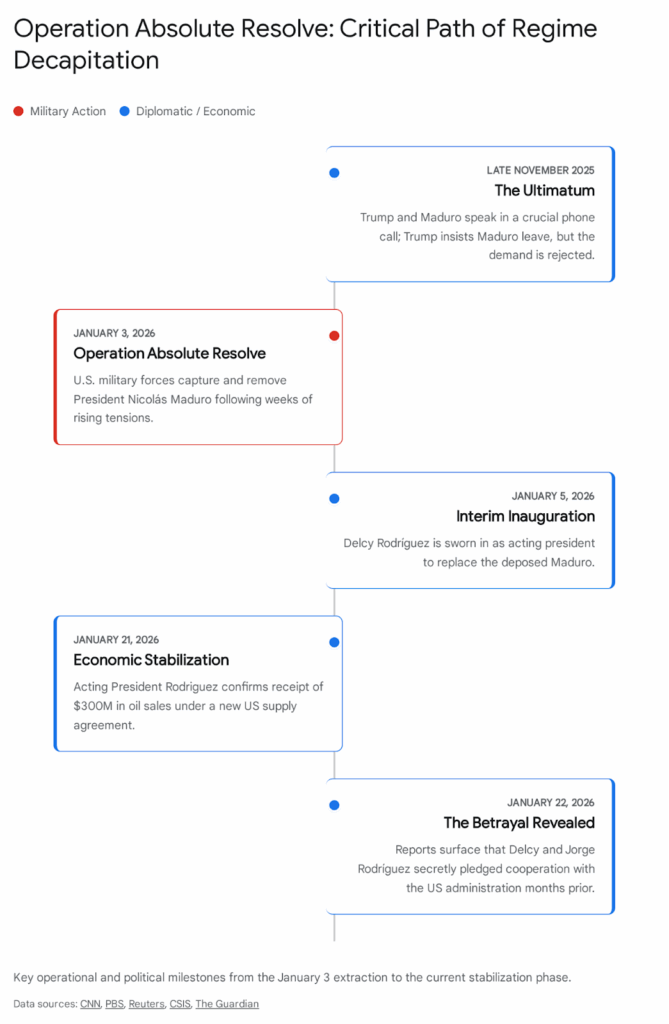

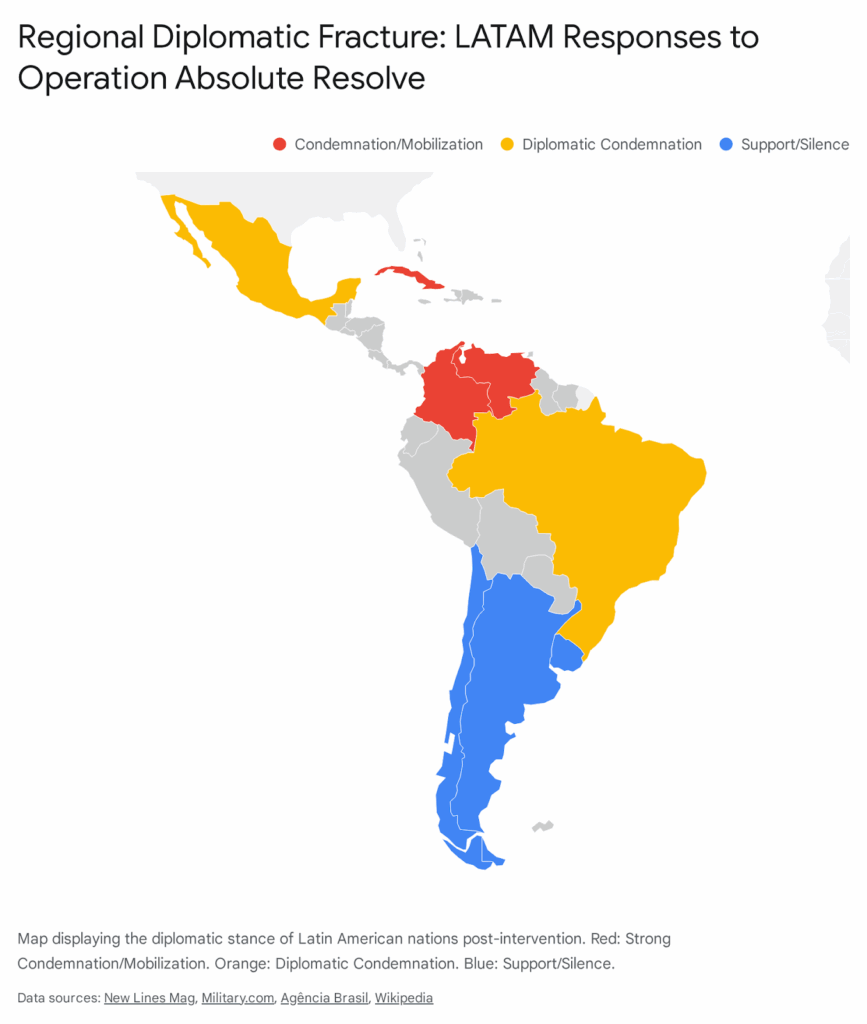

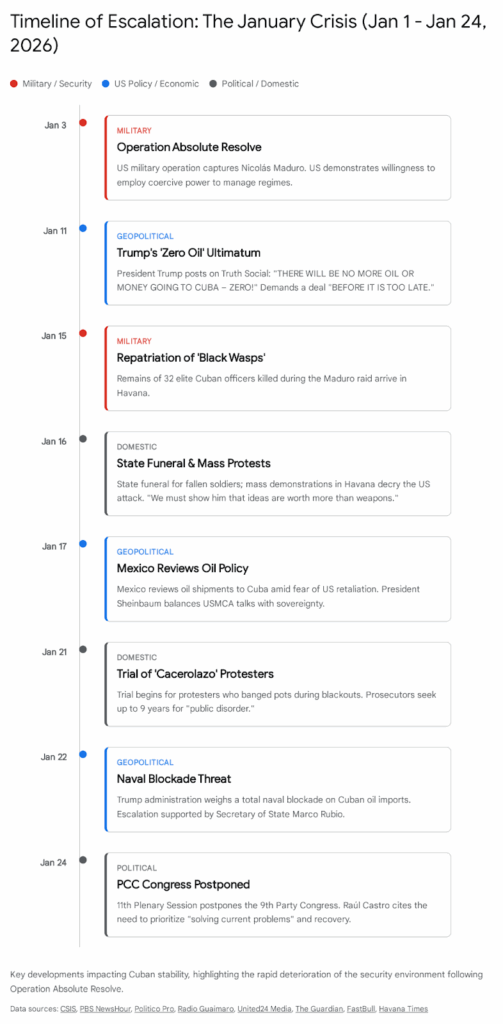

The Republic of Cuba is currently navigating its most precarious existential crisis since the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, precipitated by the tectonic geopolitical shift of January 3, 2026. The U.S. military operation in Venezuela (“Operation Absolute Resolve”), which resulted in the capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and the deaths of 32 Cuban military personnel, has severed Havana’s primary economic lifeline and shattered its implicit security guarantee. The week ending January 24, 2026, has been characterized by a frantic internal consolidation of power, signaled by the indefinite postponement of the IX Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC), and a sharp escalation in external threats, specifically the Trump administration’s active consideration of a total naval blockade to interdict oil shipments.

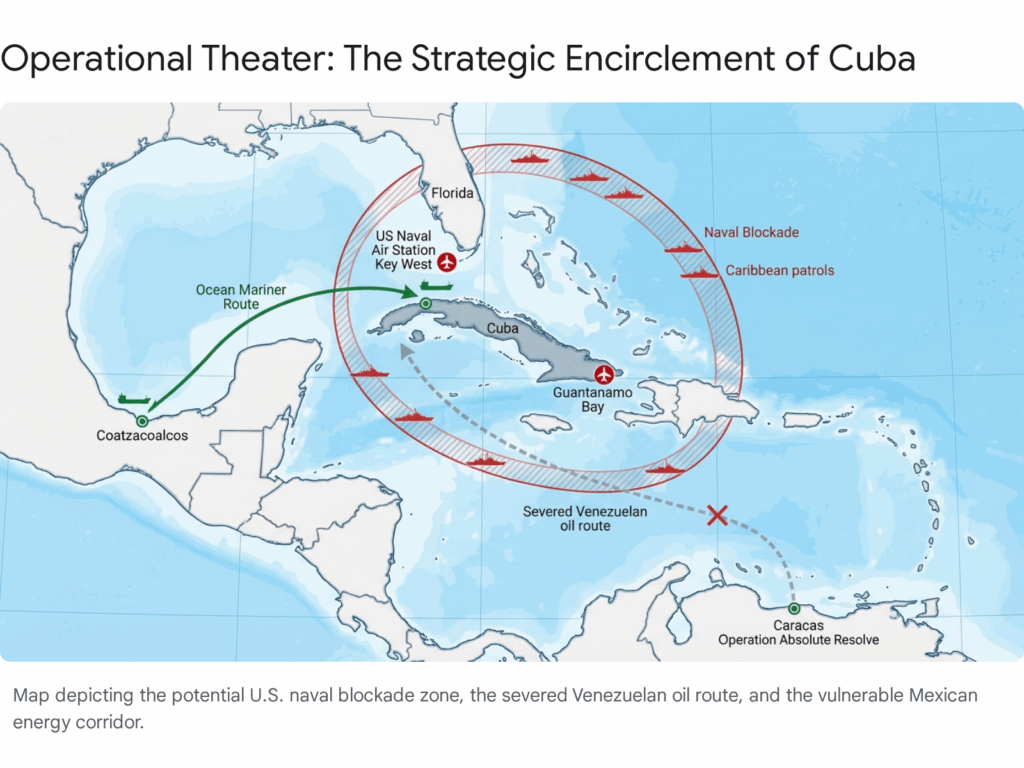

The intelligence assessment indicates that the Cuban regime is operating in a “bunker mentality,” prioritizing regime survival over all other governance functions. The decapitation of the Chavista regime in Caracas has deprived Havana of its primary patron, effectively closing the oil spigot that has sustained the island’s energy grid for two decades. In response, the regime is attempting to pivot to Mexico for energy survival, but intense U.S. diplomatic and economic pressure on the Sheinbaum administration places this alternative supply chain at high risk of interdiction.

Key Judgments

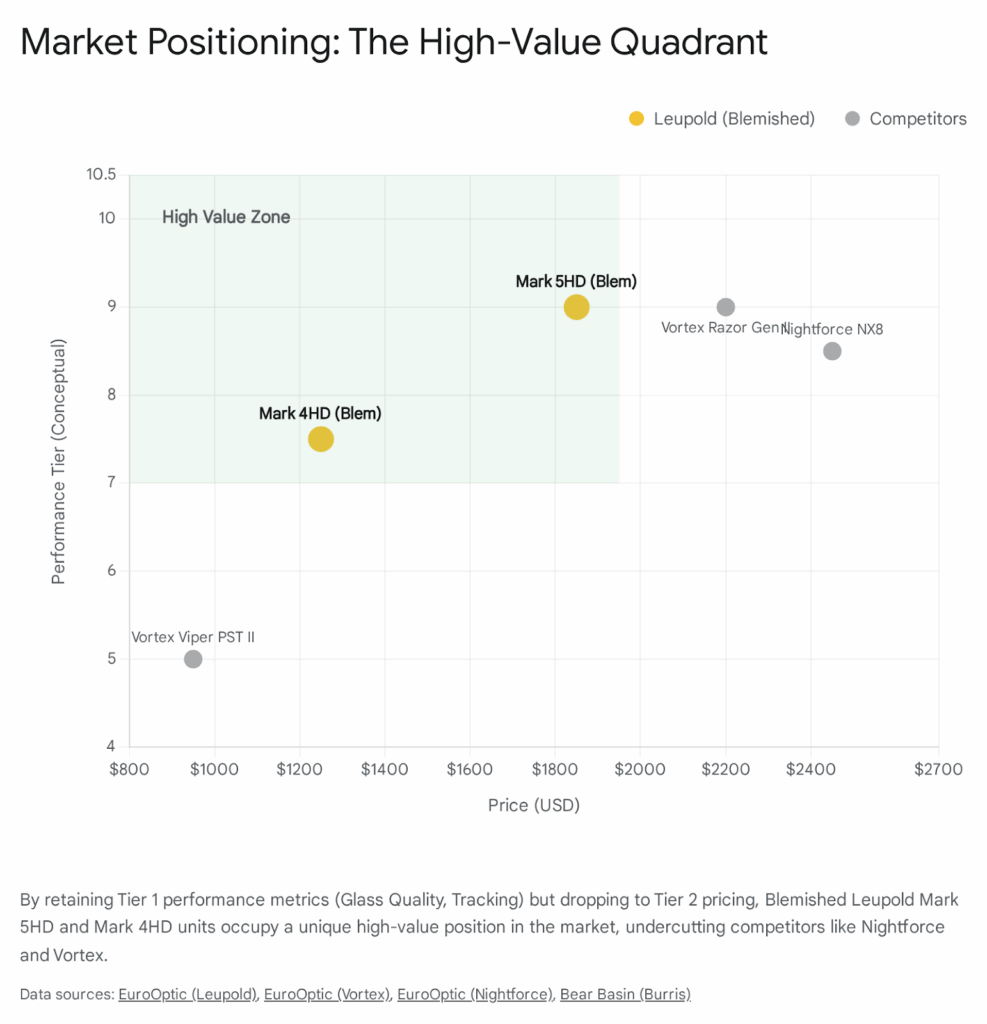

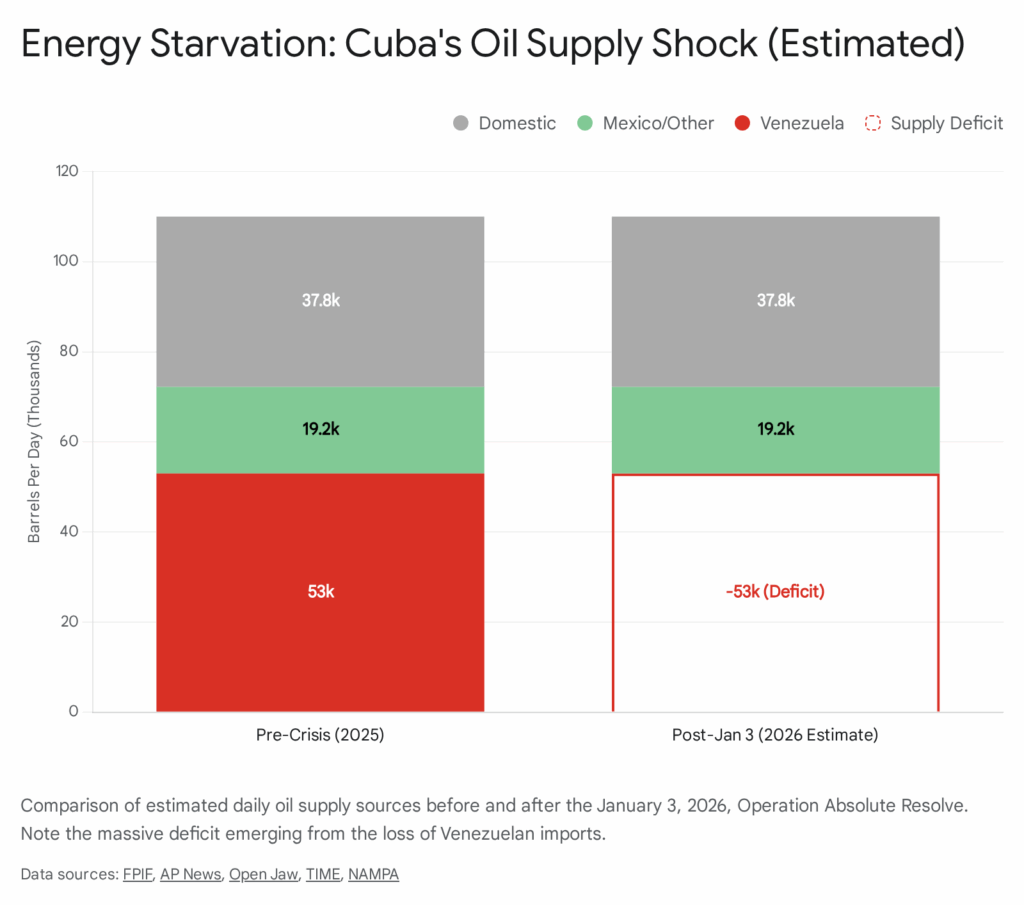

1. Strategic Isolation and the Loss of Strategic Depth: The removal of Nicolás Maduro has fundamentally altered the regional balance of power. Venezuela provided Cuba with “strategic depth”—a source of subsidized energy, financial transfers, and a political counterweight to U.S. hegemony. With U.S. forces now controlling key nodes of the Venezuelan state apparatus and President Trump declaring an end to all oil shipments to Cuba, Havana faces an immediate energy famine. The regime’s attempt to frame the conflict as a broader “anti-imperialist” struggle is failing to generate material support sufficient to offset the loss of Venezuelan crude.1

2. Regime Fragility and Paralysis: The postponement of the IX PCC Congress, originally scheduled for April 2026, indicates deep paralysis within the ruling elite. It suggests that the leadership, under First Secretary Miguel Díaz-Canel and the shadow influence of Raúl Castro, lacks a unified strategy to address the crisis. There are credible indicators of factional rifts between “continuity” hardliners and technocratic reformists who favor a “Vietnam-style” market opening. The delay is a tactical maneuver to avoid exposing these rifts during a period of extreme vulnerability.4

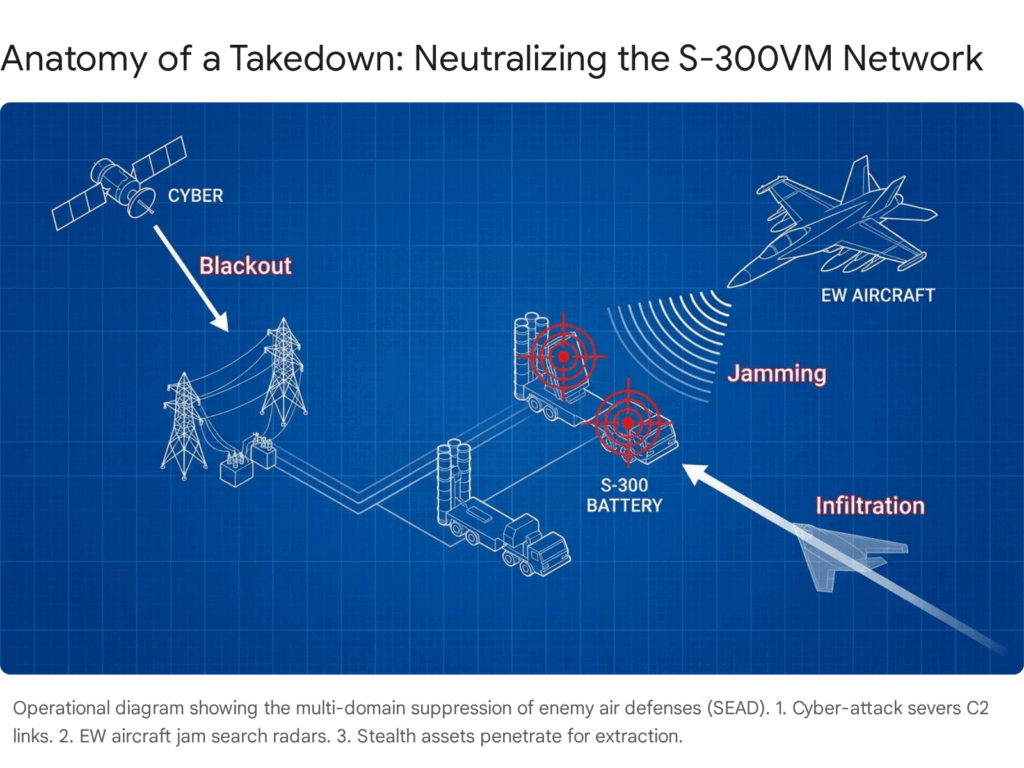

3. Military Morale Crisis: The repatriation and burial of 32 elite Cuban combatants killed during the U.S. raid in Caracas has generated a complex psychological effect. While the state is leveraging the funerals for anti-imperialist propaganda, survivor testimonies describing the “vicious” efficiency of U.S. forces have permeated the ranks of the Revolutionary Armed Forces (FAR). The stark technological asymmetry displayed during the raid has eroded the myth of resistance and highlighted the futility of conventional confrontation with the United States.6

4. Operational Risk of Naval Blockade: Intelligence indicates the U.S. National Security Council is weighing a full naval blockade to enforce an energy quarantine. Such a measure, advocated by Secretary of State Marco Rubio, would likely trigger a total collapse of the national electrical grid (SEN), potentially sparking mass civil unrest reminiscent of the July 11, 2021 (11J) protests, but with higher volatility due to the desperation of the populace. The threat alone has already created a “shadow blockade,” deterring commercial shipping.9

5. Geopolitical Hedging Limits: Russia and China have offered rhetorical support and limited aid ($80 million from Beijing), but neither appears willing to forcefully challenge a U.S. naval cordon in the Caribbean. Russia’s naval visits serve as symbolic gestures rather than credible deterrents, exposing the limits of Havana’s “great power” alliance strategy in the face of determined U.S. action in its near abroad.11

1. Strategic Context: The Post-Operation Absolute Resolve Landscape

1.1 The Geopolitical Shock of January 3rd

The geopolitical architecture of the Caribbean Basin was fundamentally altered on January 3, 2026. The U.S. execution of Operation Absolute Resolve—a precision military strike in Caracas that extracted Nicolás Maduro—has removed the linchpin of Cuba’s regional strategy. For two decades, the Venezuela-Cuba nexus was the central artery of Havana’s survival, providing subsidized oil, financial transfers, and a strategic depth that allowed the island to resist U.S. pressure.

The operation itself, characterized by its surgical nature and the overwhelming technological superiority of U.S. forces, has had a chilling effect on the Cuban leadership. The rapid collapse of Maduro’s personal security detail—comprised largely of elite Cuban operatives—demonstrated that the security guarantee Cuba provided to Venezuela was hollow in the face of direct U.S. intervention. This failure has damaged Havana’s reputation as a security provider in the Global South and has likely triggered a comprehensive review of the regime’s own defensive capabilities.1

1.2 The U.S. Policy Pivot: “Maximum Pressure” to “Regime Change”

This week witnessed a decisive shift in Washington’s posture from containment to active rollback. Emboldened by the operational success in Venezuela, the Trump administration has signaled that Cuba is the next target in a campaign to “reorder” the Western Hemisphere. The administration’s rhetoric has moved beyond traditional diplomatic condemnation to explicit threats of regime extinction.

The Blockade Threat: Intelligence reports and administration leaks, particularly those cited by Politico and The Wall Street Journal, indicate that the White House is actively debating the implementation of a total naval blockade to halt all crude oil imports to the island. This proposal, reportedly backed by Secretary of State Marco Rubio, represents a significant escalation from the traditional embargo (el bloqueo). A naval blockade is an act of war under international law. The mere threat of this action has already begun to deter third-party shippers and insurers, creating a “shadow blockade” effect even before a single U.S. Navy vessel moves to intercept.9

The Ultimatum: President Trump’s public demand for Cuba to “make a deal… before it is too late,” coupled with the explicit threat that “there will be no more oil or money going to Cuba,” frames the current U.S. strategy as an ultimatum: capitulation or collapse. The administration appears to be calculating that the Cuban regime, deprived of energy and facing a starving population, will fracture from within or face a popular uprising that renders it ungovernable. This strategy aligns with the broader “National Security Strategy” presented by Secretary Rubio, which repositions U.S. policy to aggressively assert dominance across the Western Hemisphere.2

1.3 The “Domino Theory” Revisited

The successful removal of Maduro has revitalized a version of the “domino theory” within U.S. policymaking circles, albeit in reverse. The administration views the fall of the Chavista regime as the precursor to the fall of the Castro-Canel regime. This perception drives the accelerated timeline for pressure; U.S. officials believe that Cuba is uniquely vulnerable in this specific window, struggling with a 10.9% GDP contraction (2020) followed by a shallow recovery and a renewed recession in 2025.17 The synchronization of external pressure with internal economic exhaustion is the core of the current U.S. strategy.

2. Domestic Political Stability Assessment

2.1 The Postponement of the IX Party Congress

In a move that signals profound elite insecurity, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC) announced the indefinite postponement of its IX Congress, originally scheduled for April 2026. Officially, this decision was attributed to the need to “devote 2026 to recovering” from the economic crisis, a directive that reportedly came from General Raúl Castro himself. Analytically, this represents a “state of exception” within the party apparatus.4

- Significance of the Delay: Party Congresses are the supreme mechanism for legitimizing leadership transitions, policy shifts, and five-year economic plans. By delaying the Congress, the leadership is admitting it lacks a consensus strategy to navigate the current crisis. It suggests that internal disagreements regarding the path forward—specifically between hardliners advocating for “continuity” (resistance and centralization) and reformists pushing for a “Vietnam model” of market opening—have reached an impasse.

- The Shadow of Raúl Castro: The fact that the proposal for postponement was attributed to Raúl Castro indicates that despite his retirement, he remains the ultimate arbiter of regime survival. His intervention suggests a lack of confidence in the Díaz-Canel administration’s ability to manage a high-stakes political event amidst potential social combustion. It serves as a signal to the party cadre that unity and survival take precedence over procedural norms.5

- Vietnam Comparison: Observers note the irony of the postponement given the frequent comparisons to Vietnam’s Doi Moi reforms. Unlike Vietnam, which used its 1986 Congress to launch radical economic liberalization during a crisis, the PCC appears paralyzed, opting to delay rather than decide. This hesitation increases the risk of a disorderly collapse, as the “gradualist” approach to reform has been overtaken by the speed of the economic deterioration.4

2.2 Elite Fracture and the Search for Negotiators

Reports from the Wall Street Journal suggest that the Trump administration is actively seeking “allies” within the Cuban government to negotiate a transition. While the Cuban Foreign Ministry publicly rejects such overtures, the existence of these backchannel efforts creates an atmosphere of paranoia within the Palace of the Revolution. The successful co-optation of Venezuelan elites (such as the reported cooperation of Delcy and Jorge Rodríguez prior to Maduro’s fall) serves as a terrifying precedent for the Cuban leadership.16

The regime’s counter-intelligence apparatus is likely in overdrive, scrutinizing the loyalty of senior officials in the military and economic ministries. Any official advocating for accommodation with the U.S. risks being labeled a traitor, further narrowing the space for internal debate and reinforcing the hardline stance of “resistance at all costs.”

2.3 Repression and Legal Warfare against Dissent

The regime is operating on a hair-trigger alert for civil unrest. The memory of the 11J protests looms large, and the current convergence of blackouts, food shortages, and the Venezuela shock creates a more volatile mix than existed in 2021.

- Preemptive Repression: The Prosecutor’s Office is seeking exemplary sentences (up to 9 years) for citizens involved in peaceful cacerolazos (pot-banging protests) in Villa Clara. The defendants, including independent journalist José Gabriel Barrenechea, are accused of “public disorder” for protesting blackouts. This harsh legal posture is designed to deter the population from translating energy frustration into street mobilization. The arrest of prominent opposition figure Guillermo “Coco” Fariñas while attempting to attend the trial further underscores the zero-tolerance policy.20

- Digital Authoritarianism: A new report by Prisoners Defenders exposes the extent of the “digital authoritarianism” employed by Havana. The regime utilizes a sophisticated system of monitoring to track independent social networks, essentially criminalizing dissent before it manifests physically. This “Big Brother” logic is the regime’s primary firewall against a “color revolution.” The report details how the state uses 200 distinct testimonies to map out the dismantling of independent civic networks.11

- Targeting of Journalists: The brief “kidnapping” of journalist Jorge Fernández Era by State Security and the harassment of others indicate a concerted effort to silence independent reporting on the crisis. The regime fears that independent media could serve as a catalyst for coordination among disparate protest groups.11

3. Security & Intelligence Assessment

3.1 The 32 Fallen: Repatriation and Psychological Impact

The return of the remains of 32 Cuban military and intelligence personnel killed during the defense of Maduro’s compound in Caracas has been the dominant narrative in state media this week. The regime has orchestrated a “March of the Combatant People” and elaborate funeral rites to frame these deaths as heroic sacrifices in the anti-imperialist struggle. The ceremony at the Ministry of the Revolutionary Armed Forces (MINFAR), attended by Raúl Castro and Miguel Díaz-Canel, was intended to project unity and resolve.6

However, beneath the propaganda, the incident has sent a shockwave through the Cuban security establishment (MININT and MINFAR).

- The Myth of Invincibility: For decades, Cuban military doctrine has relied on the concept of the “War of All the People” and the proficiency of its special forces (the “Black Wasps” or Avispas Negras). The swift destruction of the Cuban security detail in Caracas by U.S. forces—described by survivors as “vicious” and “disproportionate”—has exposed a stark reality: Cuban conventional forces are technologically obsolete and defenseless against modern U.S. air superiority and drone warfare.7

- Survivor Testimony: Accounts from survivors, such as Lieutenant Colonel Abel Guerra Perera, detail how U.S. Apache helicopters and drones operated with impunity, decimating the Cuban position before they could mount an effective defense. He described the attack as “ferocious,” noting that many were killed while sleeping or unarmed. Wilfredo Frómeta Tamayo, a civilian driver, recounted helicopters hovering just 100 meters away, raining debris down on them. These narratives are circulating within the barracks, potentially eroding the willingness of mid-level officers to engage in a suicidal conflict should U.S. pressure escalate to direct military action against the island.7

3.2 Asymmetric Capabilities and Threat Perception

While the conventional balance of power is overwhelmingly in favor of the U.S., the Cuban regime retains significant asymmetric capabilities. The “Big Brother” digital surveillance system remains a potent tool for internal control. Additionally, the regime maintains a capacity for irregular warfare, a doctrine that is now being re-emphasized in light of the failure of conventional defense in Venezuela.

Russian Naval Presence: The arrival of a Russian naval detachment, including the Admiral Gorshkov frigate and the Kazan nuclear-powered submarine, in Havana Bay earlier this month was intended as a signal of deterrence. However, the passivity of these assets during the Venezuela operation has reinforced the assessment that Moscow sees its Caribbean naval presence as performative rather than operational. Russia has failed to intervene to protect its “strategic partner” in Caracas, leading Cuban strategists to conclude that they cannot rely on the Kremlin for survival in a shooting war. The Russian ships, while visually imposing, are viewed by U.S. SOUTHCOM as vulnerable targets rather than credible threats in a contested environment.13

4. Economic & Infrastructure Assessment: The Meltdown

4.1 The Energy Zero Hour

Cuba’s economy is not merely in recession; it is in a state of metabolic failure due to energy starvation. The National Electric System (SEN) is operating with a deficit that frequently exceeds 1,750 MW, resulting in blackouts of up to 20 hours a day in the provinces and significant outages in Havana. This deficit represents nearly half of the national demand, which is estimated at 3,150 MW.25

- The Venezuela Gap: Prior to January 3, Venezuela supplied approximately 50,000-55,000 barrels per day (bpd) of crude and fuel oil, covering roughly half of Cuba’s import needs (total requirement ~110,000 bpd). This supply has effectively hit zero following the U.S. seizure of PDVSA assets. The SEN, which relies heavily on obsolete oil-fired thermal plants (like the Antonio Guiteras plant), cannot function without this steady inflow of heavy crude.27

- The Mexican Lifeline: In the absence of Venezuelan oil, Mexico has emerged as the supplier of last resort. The tanker Ocean Mariner, flying the Liberian flag, arrived in Havana on January 9 from the Pajaritos terminal in Coatzacoalcos, Mexico, carrying approximately 90,000 barrels of refined fuel. This shipment, while vital, serves as a mere palliative measure, providing only a few days of relief. The Ocean Mariner is one of the few vessels willing to run the gauntlet of U.S. sanctions, highlighting the extreme fragility of this supply chain.29

- Grid Collapse Risks: The Antonio Guiteras Power Plant, the backbone of the grid, remains prone to failure. The combination of fuel shortages and lack of spare parts has created a cycle of breakdowns. The “Europalius” manufacturer has noted the dire state of the grid but is restricted in its ability to intervene due to payment issues and sanctions risk.25

4.2 Economic Indicators of Collapse

The energy crisis has catalyzed a broader economic paralysis, characterized by hyperinflation and sectoral collapse.

- Currency Crisis: The informal exchange rate, tracked by independent outlet El Toque, continues to depreciate as confidence in the peso evaporates. The USD is trading at historic highs (approx. 400 CUP), while the official rate remains largely irrelevant for the average citizen. The partial dollarization of the economy has created a two-tier society, where access to foreign currency is the only buffer against starvation.34

- Inflation & Scarcity: The cost of basic goods has skyrocketed. Gasoline prices in the informal market have reached 750 pesos ($1.50 USD) per liter, a staggering sum for a population with an average monthly salary of roughly 4,200 CUP (approx. $10-15 USD in real terms). A planned official fuel price hike of 500% was postponed due to a “cyberattack,” but the economic reality forces citizens to pay black market rates or go without.36

- Sectoral Decline: Key industries are contracting at double-digit rates. Sugar, once the backbone of the economy, is down 68% over the last five years. Agriculture and fishing have collapsed by over 50%, exacerbating food insecurity. The government’s attempt to pivot to tourism is failing due to the inability to guarantee electricity and water for hotels, leading to a decline in occupancy rates despite aggressive marketing.17

- GDP Contraction: Official figures show a GDP plunge of 10.9% in 2020, followed by anemic growth and a return to recession in 2023-2024. The UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean forecasts another 1.5% decline for 2025, placing Cuba alongside Haiti as the only regional economies in recession. The loss of Venezuelan subsidies in 2026 will undoubtedly deepen this contraction significantly.17

5. Foreign Relations & Geopolitical Dynamics

5.1 The Russian Federation: A “Fair-Weather” Ally?

Moscow’s response to the U.S. intervention in Venezuela has been characterized by high-volume rhetoric and low-impact action. The Russian Foreign Ministry has issued statements condemning the U.S. “blackmail,” “cowardice,” and violation of sovereignty, urging the release of Maduro. However, the Kremlin has taken no concrete steps to reverse the situation in Caracas or challenge the U.S. naval dominance in the Caribbean.12

- Strategic Calculation: Analysts assess that Putin is prioritizing his campaign in Ukraine and is unwilling to open a second front in the Western Hemisphere. The “loss” of Venezuela and the potential fall of Cuba are viewed in Moscow as symbolic blows but acceptable costs to avoid a direct military confrontation with the U.S. Navy. The Russian warships in Havana, including the Admiral Gorshkov, serve as a “show of force” for domestic Russian consumption rather than a credible threat to the U.S. Southern Command (SOUTHCOM). The failure of Russian intelligence or military assets to prevent the capture of Maduro has tarnished Moscow’s reputation as a security partner.12

5.2 The People’s Republic of China: Cautious Sustainment

China remains Cuba’s most significant economic partner outside of the immediate region. The recent announcement of an $80 million aid package (including rice, aspirin, and electrical equipment) demonstrates Beijing’s commitment to preventing a total humanitarian collapse. The aid was confirmed during a meeting between the Chinese Ambassador and President Díaz-Canel.11

- Limits of Support: However, Beijing is notably cautious. While it supports Cuba’s sovereignty diplomatically, there is no indication that China is willing to backfill the oil deficit left by Venezuela or extend massive new credit lines to a borrower that has repeatedly defaulted. China’s strategy appears to be one of “palliative care”—keeping the regime on life support without investing the capital required to cure its structural ills. The Chinese Foreign Ministry has emphasized “humanitarian” support rather than military or strategic commitments that would provoke Washington.40

5.3 Mexico’s Dilemma

Mexico finds itself in the crosshairs of the U.S. pressure campaign. President Claudia Sheinbaum has publicly stated that Mexico will continue to send oil to Cuba as an “act of solidarity,” emphasizing humanitarian reasons. However, reports indicate that her administration is internally reviewing this policy due to threats from the Trump administration regarding the upcoming USMCA trade review. The Ocean Mariner shipment has become a focal point of this tension. If the U.S. implements a naval blockade, Mexico will face a binary choice: defy the U.S. Navy and risk its own economic stability, or abandon Cuba.30

6. Humanitarian & Social Dynamics

6.1 The Migration Hemorrhage

The deterioration of conditions on the island is fueling a desperate exodus. Demographic data indicates that Cuba’s population has likely fallen below 8 million, a decline of over 25% in just four years (down from 11 million). This “demographic hemorrhage” is depriving the country of its working-age population and professional class. The exodus is driven by a total loss of hope in the future of the country, with 78% of Cubans surveyed expressing a desire to leave.1

- U.S. Enforcement: In response to the potential for a mass migration event (a “Mariel 2.0”), the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the Coast Guard have adopted an aggressive interdiction posture. Recent statistics show a continued high tempo of repatriations (e.g., 103 aliens repatriated in early FY2025). The U.S. message is clear: the maritime border is closed. This enforcement creates a “pressure cooker” effect on the island, as the traditional safety valve of emigration is throttled, increasing the likelihood of internal explosion.46

6.2 Health and Food Security Crisis

The humanitarian situation is reaching catastrophic levels.

- Food Insecurity: A staggering 89% of Cuban families live in extreme poverty, and 7 out of 10 Cubans must forgo at least one daily meal. The collapse of domestic agriculture means the country is almost entirely dependent on imports it can no longer afford.1

- Public Health: The once-renowned healthcare system is in ruins. Only 3% of citizens can obtain medicines at pharmacies. Reports of a possible Hepatitis outbreak in Ciego de Ávila and the spread of arboviruses like Oropouche, Zika, and Dengue are compounding the misery. The shortage of hygiene products and clean water (due to power outages affecting pumps) creates ideal conditions for epidemics.1

6.3 The Shadow of “11J” and Political Prisoners

The regime holds over 1,000 political prisoners, many from the July 11, 2021 protests. Organizations like Justicia 11J and Prisoners Defenders continue to document abuses in prisons, including torture and denial of medical care. The release of some prisoners in Venezuela has not been mirrored in Cuba; instead, the crackdown has intensified. The death of a Cuban migrant in U.S. custody (Geraldo Lunas Campos) has also been used by state media to discourage migration, but the internal repression remains the primary driver of discontent.17

7. Conclusions & Outlook

7.1 Scenario Analysis

The Cuban regime is currently trapped in a negative feedback loop: the energy crisis causes economic paralysis, which fuels social unrest, which necessitates increased repression, which further isolates the regime and deters foreign investment.

- Scenario A: The “Special Period” 2.0 (Most Likely Short-Term): The regime survives the immediate shock by implementing draconian austerity measures, relying on harsh repression to quell dissent, and securing just enough oil from Mexico and the gray market to keep critical infrastructure (military, hospitals) running. The population descends into extreme poverty, but the security apparatus remains cohesive. The PCC postponement allows the elite to circle the wagons.

- Scenario B: The Energy Triggered Collapse (Moderate Probability): A total failure of the SEN, lasting several days in Havana, triggers spontaneous, island-wide protests that overwhelm the security forces. Mid-level military commanders refuse to fire on civilians, leading to a fracture in the leadership and a chaotic transition or civil conflict.

- Scenario C: U.S. Naval Blockade (Low to Moderate Probability): The Trump administration moves forward with a formal blockade. This would constitute an act of war. While it would accelerate the economic strangulation, it could also rally nationalist sentiment within the FAR and provide the regime with a clear external enemy to blame for the suffering, potentially prolonging its survival in a “bunker” mentality.

7.2 Indicators for Watchlist

Analysts should prioritize the monitoring of the following indicators in the coming week:

- Tanker Tracking: The movement of the Ocean Mariner and any other vessels attempting to breach the de facto energy cordon.

- Grid Stability: Frequency and duration of blackouts in Havana specifically.

- Military Movements: Any unusual deployment of the “Black Wasps” or special forces within urban centers, indicating anticipation of unrest.

- Diplomatic Cables: Signs of a break or strain in Mexico-U.S. relations over the oil issue.

- Health Alerts: Confirmation of the scope of the Hepatitis outbreak in Ciego de Ávila.

End of Report

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- The Geopolitics of Maduro’s Capture: Cuba’s Inflection Point, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.csis.org/analysis/geopolitics-maduros-capture-cubas-inflection-point

- Trump tells Cuba to ‘make a deal’ or face the consequences – The Guardian, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2026/jan/11/trump-tells-cuba-to-make-a-deal-or-face-the-consequences

- 2026 United States intervention in Venezuela – Wikipedia, accessed January 24, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2026_United_States_intervention_in_Venezuela

- Cuba: Reform or Blackout, accessed January 24, 2026, https://havanatimes.org/opinion/cuba-reform-or-blackout/

- Agreement of the 11th Plenary Session of the Central Committee to postpone the holding of the 9th Party Congress, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.radioguaimaro.icrt.cu/en/news/cuba/agreement-of-the-11th-plenary-session-of-the-central-committee-to-postpone-the-holding-of-the-9th-party-congress

- Cuba Brings Home 32 Special Forces Killed During US Capture of Maduro—Who Were They? – UNITED24 Media, accessed January 24, 2026, https://united24media.com/latest-news/cuba-brings-home-32-special-forces-killed-during-us-capture-of-maduro-who-were-they-15106

- “They were vicious against us,” says survivor of military aggression …, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.radioangulo.cu/en/2026/01/17/they-were-vicious-against-us-says-survivor-of-military-aggression-against-venezuela/

- The weight of death / All that remains is the pain that we couldn’t stop them, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.radioreloj.cu/features/the-weight-of-death-all-that-remains-is-the-pain-that-we-couldnt-stop-them/

- Is Cuba next? Trump team debates oil cutoff to topple Havana’s leadership, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.indiatoday.in/world/story/after-venezuela-trump-eyes-cuba-as-oil-blockade-plan-fuels-regime-change-push-2857048-2026-01-24

- E&E News: White House weighs naval blockade to halt Cuban oil imports, accessed January 24, 2026, https://subscriber.politicopro.com/article/eenews/2026/01/23/trump-administration-weighs-naval-blockade-to-halt-cuban-oil-imports-pro-00744886

- Month: January 2026 – Translating Cuba, accessed January 24, 2026, https://translatingcuba.com/2026/01/

- The Geopolitics of Maduro’s Capture: What Does Operation Absolute Resolve Mean for Russia? – CSIS, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.csis.org/analysis/geopolitics-maduros-capture-what-does-operation-absolute-resolve-mean-russia

- Russian warships arrive in Cuban waters for military exercises | PBS News, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/russian-warships-arrive-in-cuban-waters-for-military-exercises

- Prosecution of Nicolás Maduro and Cilia Flores – Wikipedia, accessed January 24, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prosecution_of_Nicol%C3%A1s_Maduro_and_Cilia_Flores

- ‘The acceleration of the inevitable’: What does the post-Venezuelan oil reality hold for Cuba?, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.wlrn.org/government-politics/2026-01-20/cuba-venezuelan-oil-econony-miami

- Trump administration eyes Cuba regime change after Venezuela success: WSJ, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.thestandard.com.hk/world-news/article/322390/Trump-administration-eyes-Cuba-regime-change-after-Venezuela-success-WSJ

- ‘History will tell’: as US pressure grows, Cuba edges closer to collapse amid mass exodus – The Guardian, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2026/jan/10/cuba-regime-polycrisis-collapse-exodus-economy-migration-us-sanctions-trump

- Cuba’s communist party postpones congress, citing economic crisis – Indo Premier Sekuritas, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.indopremier.com/ipotnews/newsDetail.php?jdl=Cuba_s_communist_party_postpones_congress__citing_economic_crisis&news_id=1714288&group_news=ALLNEWS&news_date=&taging_subtype=CUBA&name=&search=y_general&q=CUBA,%20&halaman=1

- Venezuela’s Delcy Rodríguez assured US of cooperation before Maduro’s capture, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/22/delcy-rodriguez-capture-maduro-venezuela

- Cuba: Prosecutor Seeks 9 Years for Pots & Pans Protesters – Havana Times, accessed January 24, 2026, https://havanatimes.org/features/cuba-prosecutor-seeks-9-years-for-pots-pans-protesters/

- Cuba: Warning about the escalation of repression against activists and human rights defenders four years after the 11J protests – Race and Equality, accessed January 24, 2026, https://raceandequality.org/resources/cuba-warning-about-the-escalation-of-repression-against-activists-and-human-rights-defenders-four-years-after-the-11j-protests/

- Cuban Soldier Describes His Experience During Raid That Captured Maduro: ‘It Was Disproportionate’, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.latintimes.com/cuban-soldier-describes-his-experience-during-raid-that-captured-maduro-it-was-disproportionate-593613

- Russian warships arrive in Cuba in show of force | BBC News – YouTube, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YT42sUavVG8

- Cubans say Russian warships, including nuclear-powered submarine, will arrive in Havana next week – PBS, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/cubans-say-russian-warships-including-nuclear-powered-submarine-will-arrive-in-havana-next-week

- Europalius Addresses Energy Service Disruptions in Cuba Amid National Power Crisis – weareiowa.com, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.weareiowa.com/article/news/local/plea-agreement-reached-in-des-moines-murder-trial/524-3069d9d4-6f9b-4039-b884-1d2146bd744f?y-news-28261022-2026-01-16-europalius-addresses-energy-service-disruptions-cuba-2026

- Cuba’s Electricity Crisis: What’s Happening and What Comes Next – The University of Alabama at Birmingham, accessed January 24, 2026, https://sites.uab.edu/humanrights/2025/10/10/cubas-electricity-crisis-whats-happening-and-what-comes-next/

- Trump Can’t Make Cuba Great Again. Only Cubans Can Do It., accessed January 24, 2026, https://time.com/7344661/cuba-trump-venezuela-oil-economy-crisis/

- Why Cuba Is Back on Washington’s Regime-Change Agenda – FPIF, accessed January 24, 2026, https://fpif.org/why-cuba-is-back-on-washingtons-regime-change-agenda/

- Mexico Oil Shipment Reaches Cuba, Increasing Tensions With US – gCaptain, accessed January 24, 2026, https://gcaptain.com/mexico-oil-shipment-reaches-cuba-increasing-tensions-with-us/

- Mexico becomes crucial fuel supplier to Cuba but pledges no extra shipments | AP News, accessed January 24, 2026, https://apnews.com/article/mexico-cuba-petroleum-oil-shipments-trump-venezuela-7ec85826c98f23226c2534954b2c2b6f

- Two oil tankers spotted entering Cuba bay over past 2 days, despite US restriction efforts, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xuFVoQFCuFU

- OCEAN MARINER, Chemical/Oil Products Tanker – Details and current position – IMO 9328340 – VesselFinder, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.vesselfinder.com/vessels/details/9328340

- 2024–2025 Cuba blackouts – Wikipedia, accessed January 24, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2024%E2%80%932025_Cuba_blackouts

- Cuba’s Currency Crisis Deepens Amid Inflation and Shortages | Mayberry Investments Limited, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.mayberryinv.com/cubas-currency-crisis-deepens-amid-inflation-and-shortages/

- Cuba Ups Its Official Purchase Rate for US Dollars by 500% | elTOQUE, accessed January 24, 2026, https://eltoque.com/en/cuba-ups-its-official-purchase-rate-for-us-dollars-by-500percent

- Gasoline Reaches 750 Pesos ($1.50 USD) per Liter in Havana, accessed January 24, 2026, https://havanatimes.org/news/gasoline-reaches-750-pesos-1-50-usd-per-liter-in-havana/

- Cuba postpones 400% increase in fuel prices following ‘foreign’ computer attack – EFE, accessed January 24, 2026, https://efe.com/en/latest-news/2024-01-31/cuba-postpones-400-increase-in-fuel-prices-following-foreign-computer-attack/

- Statement by Permanent Representative Vassily Nebenzia at a UNSC Briefing on Venezuela – Permanent Mission of the Russian Federation to the United Nations, accessed January 24, 2026, https://russiaun.ru/en/news/05012026

- Foreign Ministry statement concerning developments around Venezuela, accessed January 24, 2026, https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/2070938/

- Xi Jinping approves new round of aid from the People’s Republic of China to Cuba, accessed January 24, 2026, https://socialistchina.org/2026/01/22/xi-jinping-approves-new-round-of-aid-from-the-peoples-republic-of-china-to-cuba/

- Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Mao Ning’s Regular Press Conference on January 7, 2026, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/eng/xw/fyrbt/202601/t20260107_11807882.html

- China underscores support for Cuba after new US threats | Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Cuba – CubaMinrex, accessed January 24, 2026, https://cubaminrex.cu/en/china-underscores-support-cuba-after-new-us-threats

- Mexico will continue sending oil to Cuba despite US blockade, Sheinbaum says, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/energy/general/mexico-will-continue-sending-oil-to-cuba-despite-us-blockade-sheinbaum-says/54206

- The Trump administration turns attention to Mexico and Cuba’s oil relationship, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.kbia.org/2026-01-19/the-trump-administration-turns-attention-to-mexico-and-cubas-oil-relationship

- Mexico Reviews Cuba Oil Shipments Amid US Pressure – FastBull, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.fastbull.com/news-detail/mexico-reviews-cuba-oil-shipments-amid-us-pressure-4368278_0

- Coast Guard repatriates 5 aliens to Cuba, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.news.uscg.mil/Press-Releases/Article/4192770/coast-guard-repatriates-5-aliens-to-cuba/

- Coast Guard repatriates 82 people to Cuba, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.news.uscg.mil/Press-Releases/Article/3377581/coast-guard-repatriates-82-people-to-cuba/

- Cuba: Protesters Detail Abuses in Prison | Human Rights Watch, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/07/11/cuba-protesters-detail-abuses-in-prison

- Death of Cuban migrant in Texas facility officially classified as homicide, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2026/jan/23/cuban-migrant-death-texas-ice-homicide