Executive Summary

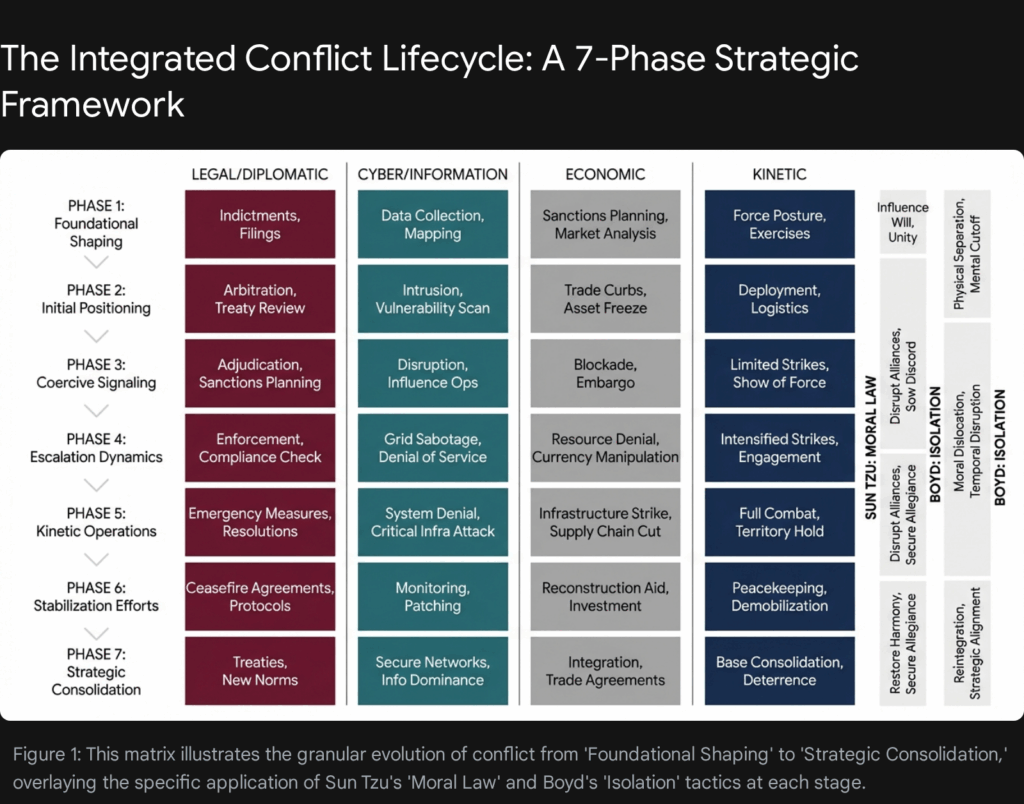

The geopolitical landscape of the early 21st century has definitively shifted from the linear, state-centric models of the post-Westphalian order to a complex, fluid ecosystem of “Gray Zone” conflict. In this environment, the boundaries between peace and war are not merely blurred; they are deliberately weaponized. This report provides an exhaustive strategic analysis of this evolution, proposing a granular Seven-Phase Conflict Lifecycle Model that synthesizes the ancient strategic wisdom of Sun Tzu with the kinetic and cognitive theories of Colonel John Boyd.

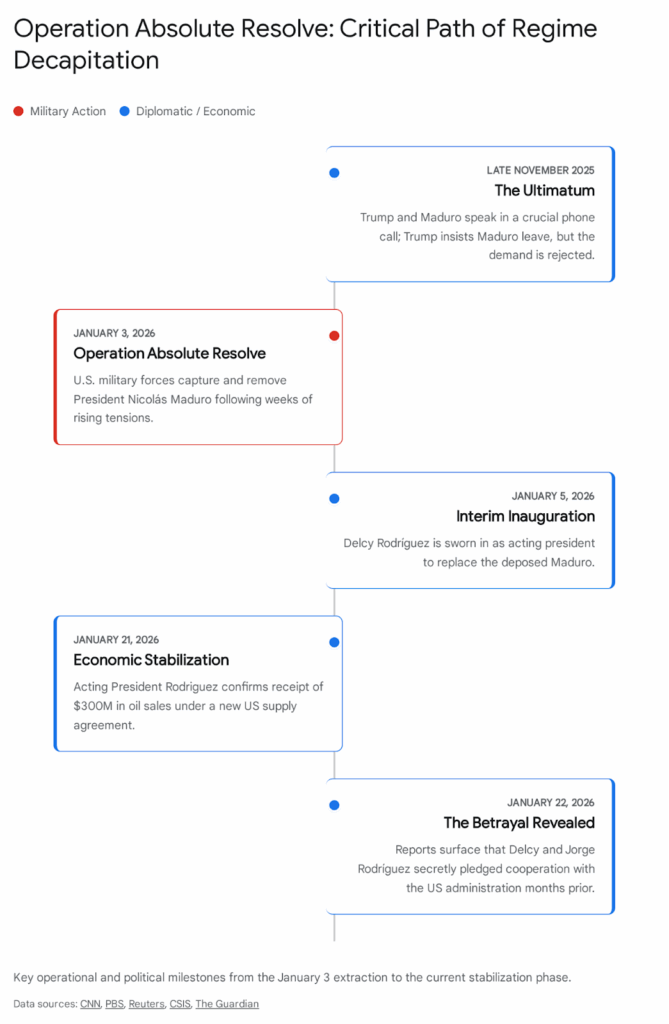

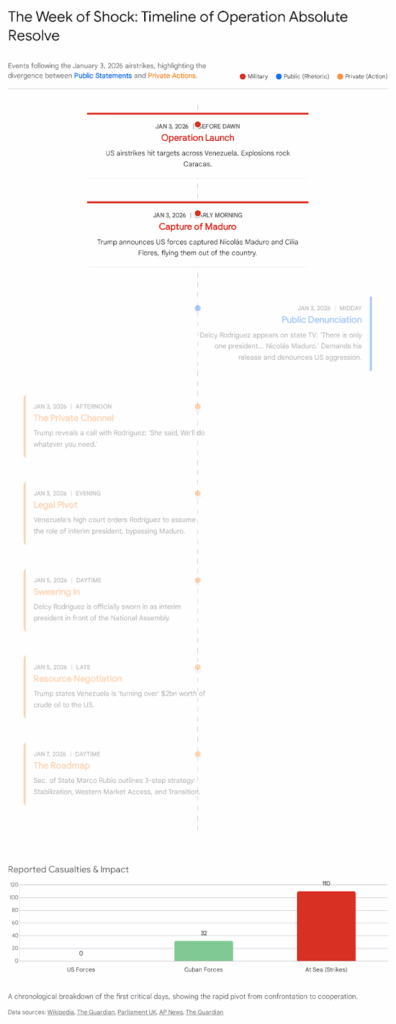

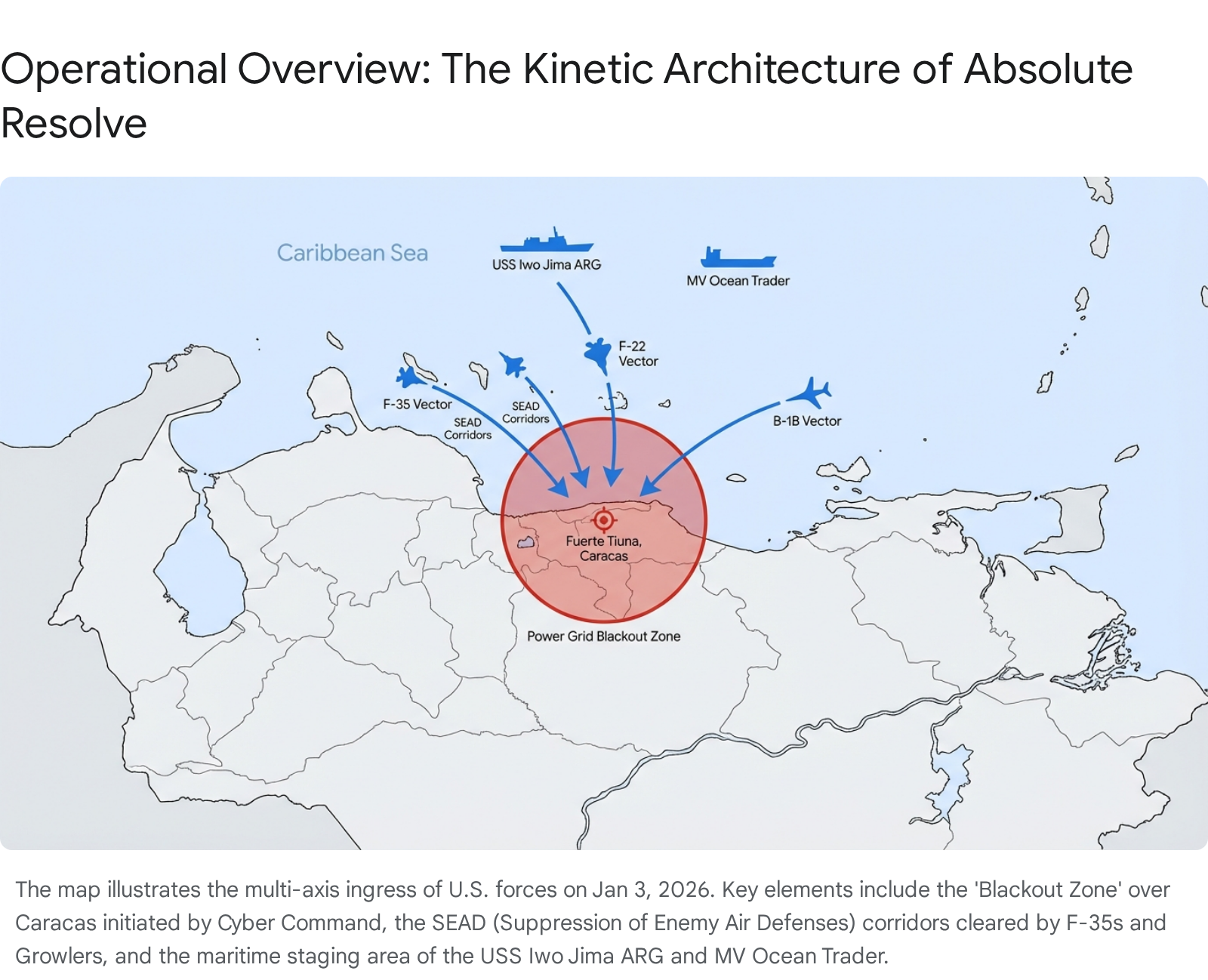

This theoretical framework is applied with rigorous detail to the watershed event of January 3, 2026: Operation Absolute Resolve, the U.S. decapitation strike that resulted in the capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. Unlike the catastrophic failure of Operation Gideon in 2020, which suffered from amateurish operational security and a lack of multi-domain integration, Absolute Resolve demonstrated a mastery of “Layered Ambiguity”—the precise synchronization of lawfare, cyber-physical disruption, economic strangulation, and surgical kinetic action.

The analysis, derived from a team perspective integrating national security, intelligence, and warfare strategy disciplines, confirms that modern regime degradation is rarely achieved through brute force attrition. Instead, success relies on “Folding the Adversary’s OODA Loop”—creating a state of cognitive paralysis where the target cannot Orient or Decide before systemic collapse is inevitable. The operation in Caracas was not merely a military raid; it was the culmination of a six-year campaign of “foundational shaping” that utilized federal indictments, economic warfare, and cognitive operations to strip the regime of its legitimacy and defensive capacity long before the first rotor blade turned.

Top 20 Strategic Insights: Summary Table

| Rank | Insight Category | Core Strategic Observation |

| 1 | Cognitive Paralysis | Victory in modern conflict is defined by the inability of the adversary to process information (Orientation), leading to systemic collapse rather than physical annihilation. 1 |

| 2 | Lawfare as Artillery | Federal indictments function as long-range “preparatory fires,” isolating leadership and creating legal justifications (e.g., “Narco-Terrorism”) for later kinetic extraction. 3 |

| 3 | The OODA “Fold” | Success requires operating inside the adversary’s decision cycle at a tempo that induces “entropy,” causing their system to implode from within. 1 |

| 4 | Cyber-Physical Bridge | Cyber capabilities are most effective when they manifest physical effects (e.g., the Caracas power grid disruption) that degrade command and control (C2) during kinetic windows. 6 |

| 5 | The “Cheng/Ch’i” Dynamic | Modern strategy requires a “Cheng” (direct) element, such as sanctions, to fix the enemy, while the “Ch’i” (indirect) element, like the surgical raid, delivers the blow. 5 |

| 6 | Intelligence Dominance | The shift from “Shock and Awe” to “Surgical Extraction” relies entirely on granular “Pattern of Life” intelligence, down to the target’s diet and pets. 8 |

| 7 | Economic Pre-Positioning | Economic warfare is not just punishment; it is a shaping operation to degrade critical infrastructure maintenance (e.g., Venezuelan radar readiness) prior to conflict. 9 |

| 8 | Electronic Warfare (EW) | The suppression of enemy air defenses (SEAD) is now primarily non-kinetic; EW platforms like the EA-18G Growler are the “breaching charges” of modern air raids. 10 |

| 9 | Operational Security (OPSEC) | The failure of Operation Gideon (2020) was rooted in the reliance on commercial encrypted apps (Signal/WhatsApp), whereas Absolute Resolve utilized secure, proprietary military networks. 11 |

| 10 | Gray Zone Deterrence | Traditional nuclear deterrence does not apply in the Gray Zone; deterrence must be “punitive and personalized,” targeting leadership assets rather than national populations. 13 |

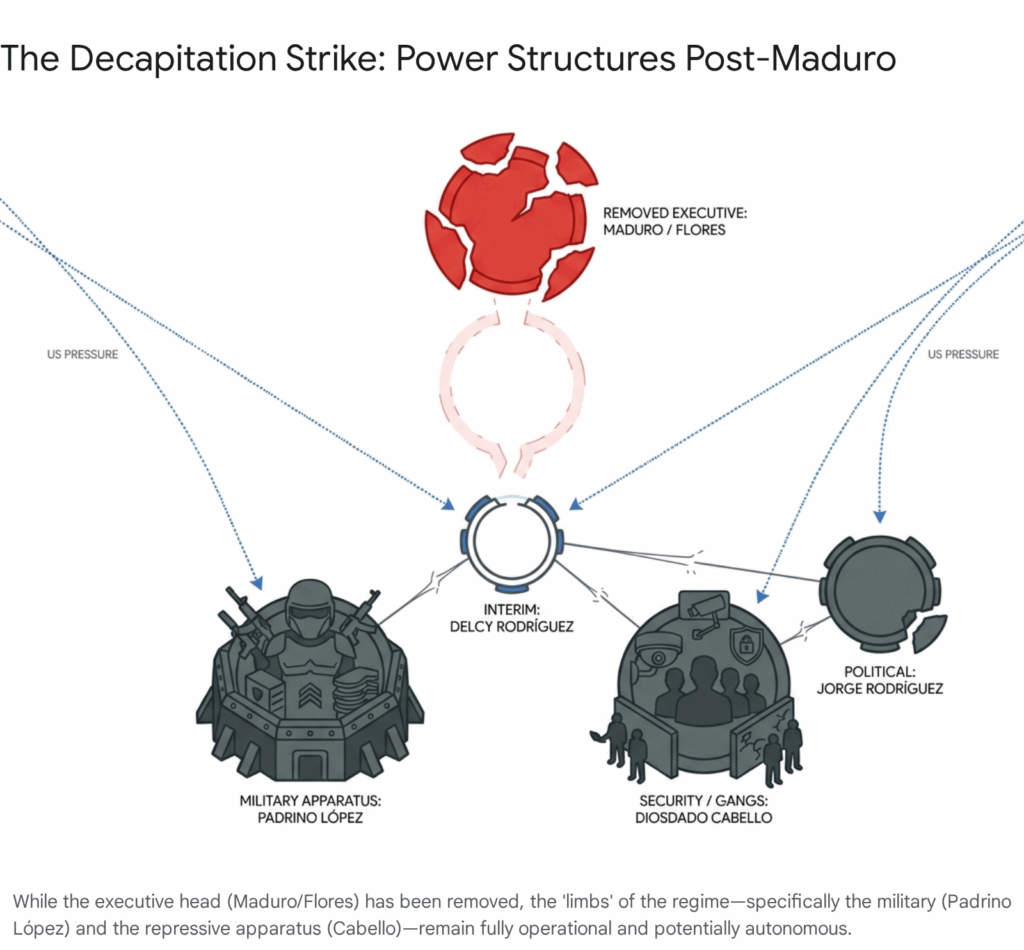

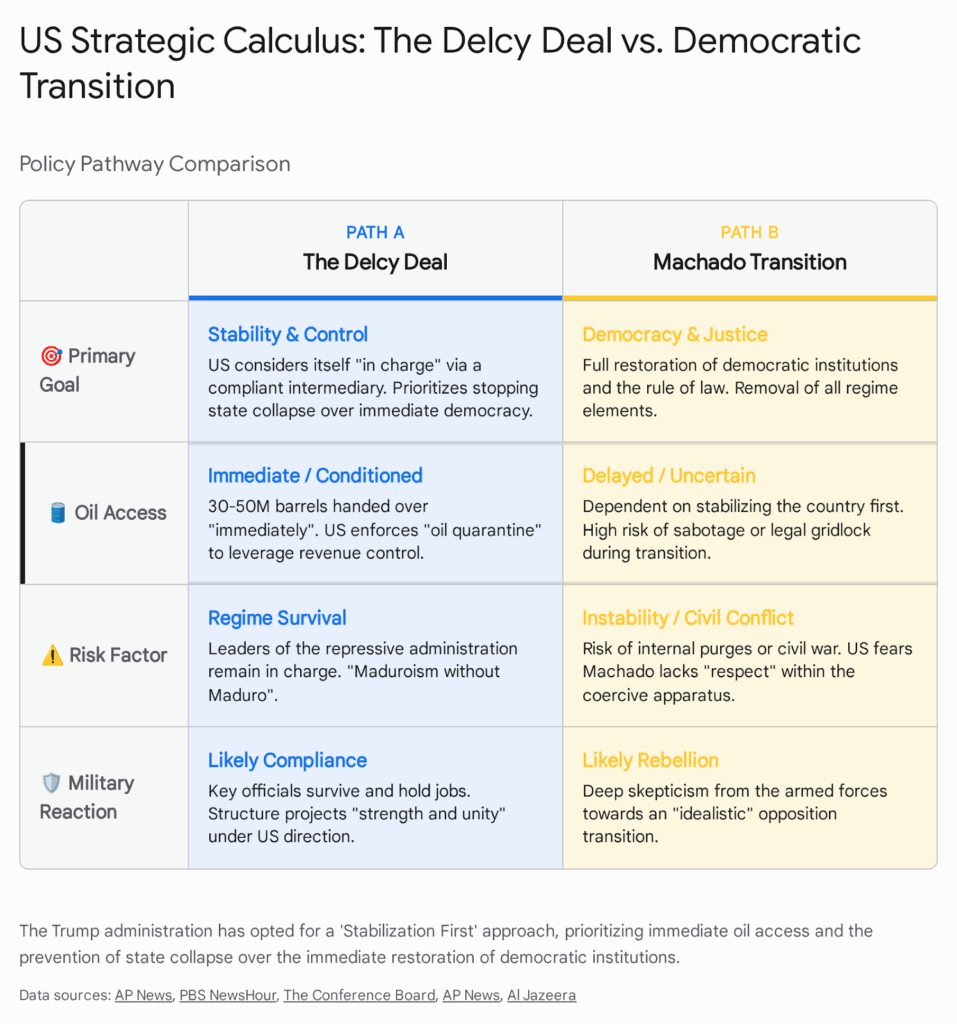

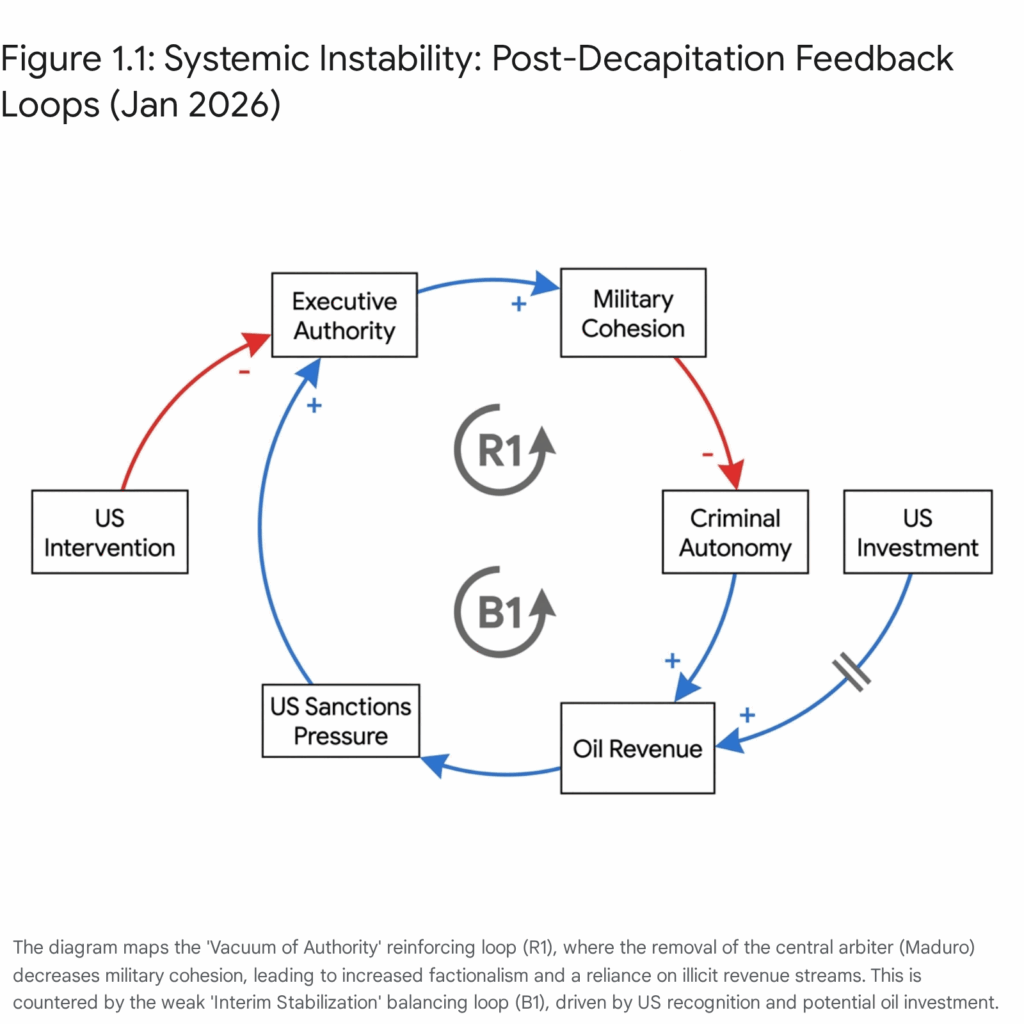

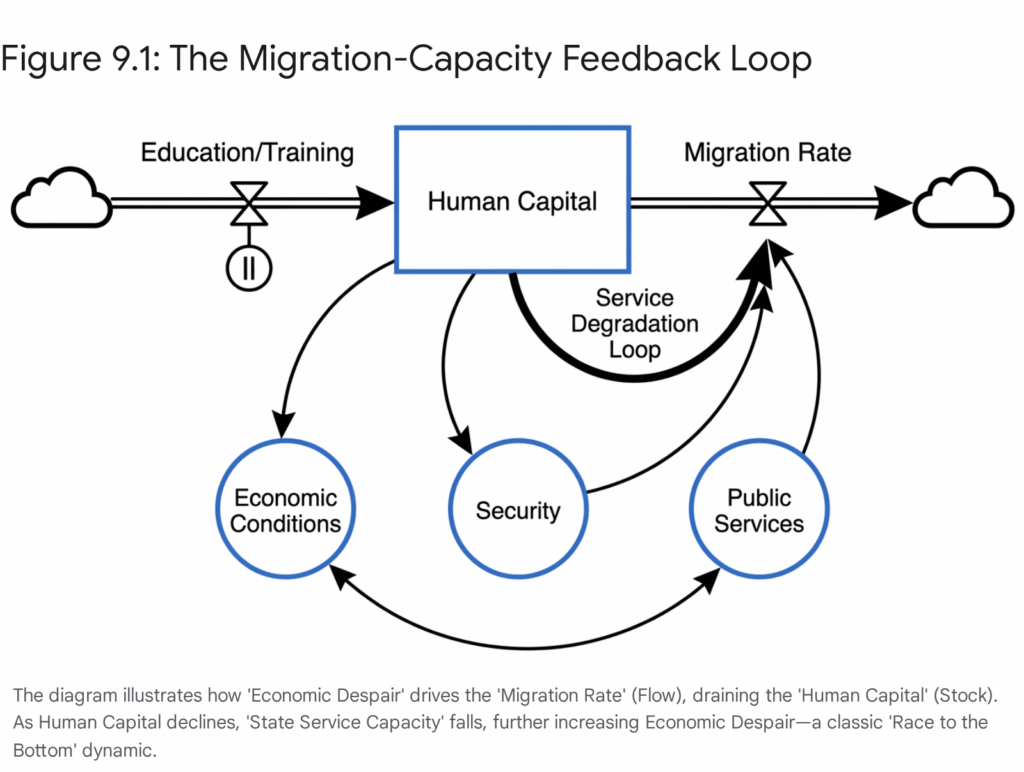

| 11 | The Vacuum Phase | The most critical risk period is immediately post-decapitation, requiring rapid “Transitional Stabilization” to prevent civil war or criminal anarchy. 14 |

| 12 | Sovereignty Redefined | The designation of “non-international armed conflict” against criminal cartels allows states to bypass traditional sovereignty claims during extraction operations. 15 |

| 13 | Visual Supremacy | Control of the visual narrative (e.g., live feeds, satellite imagery) is essential to define the “truth” of the operation before the adversary can spread disinformation. 16 |

| 14 | Alliance “Severing” | Sun Tzu’s dictum to “attack the enemy’s alliances” was realized by diplomatically isolating Venezuela from Russia/China prior to the strike. 17 |

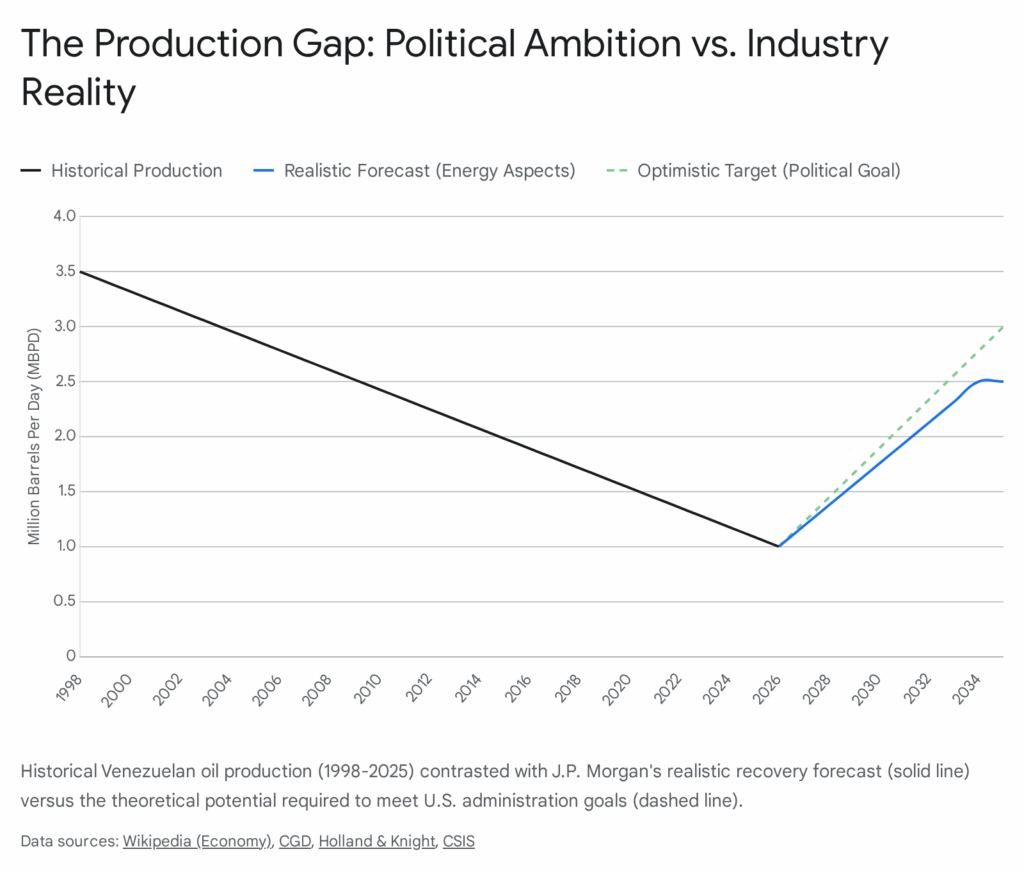

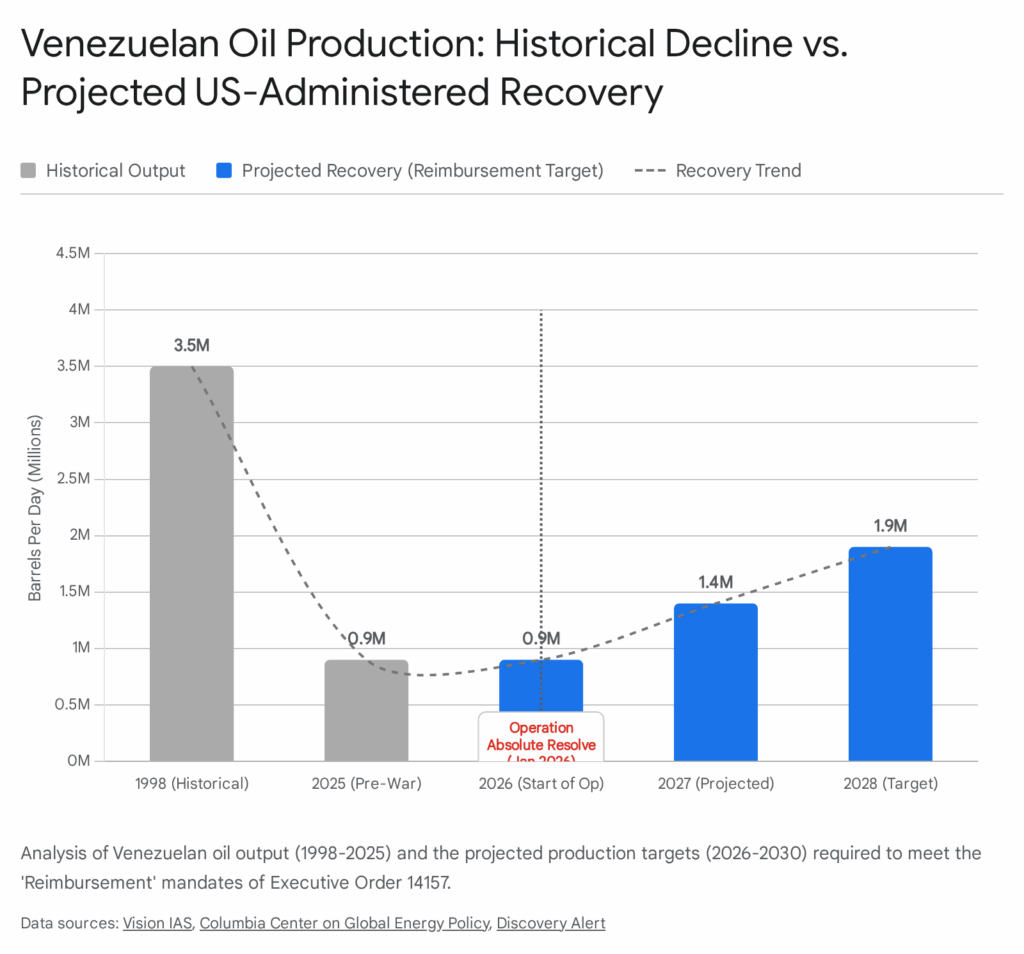

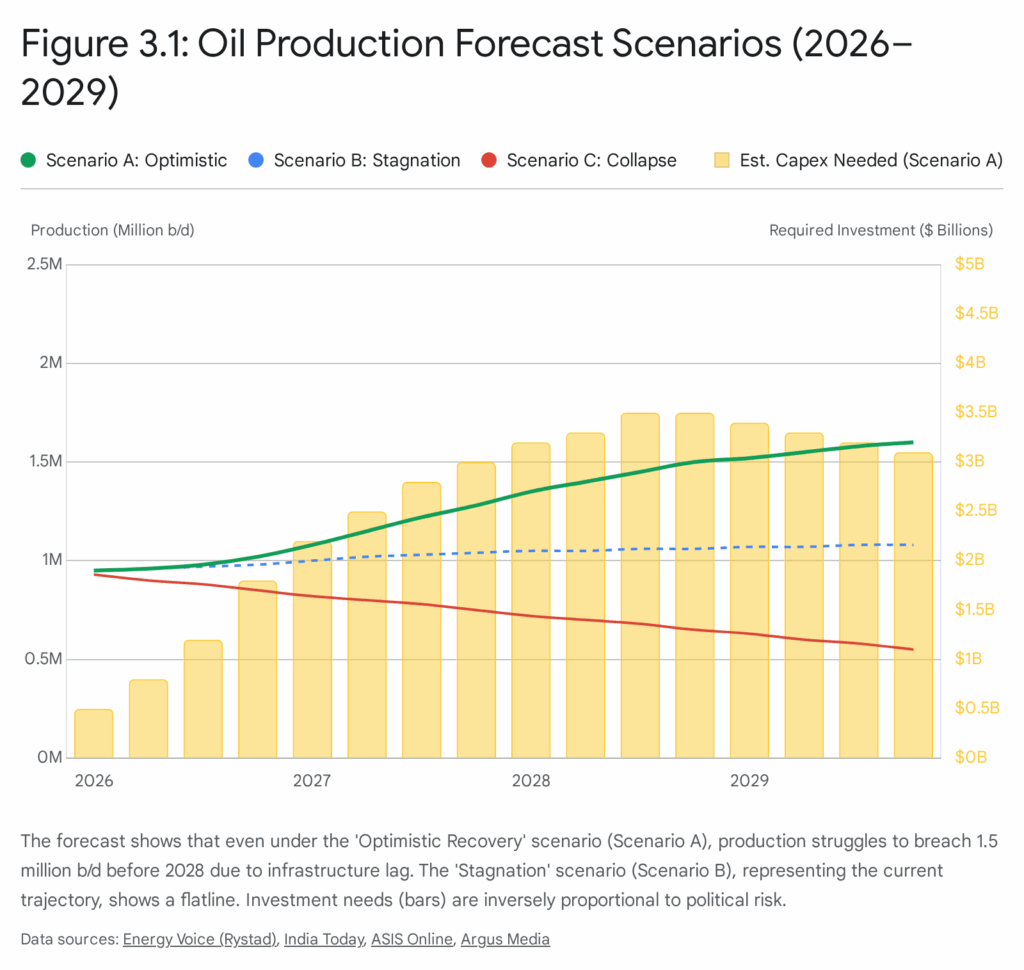

| 15 | Energy Realpolitik | The immediate post-operation oil deals (50m barrels) highlight the inseparable link between regime change operations and global energy security logistics. 6 |

| 16 | The “Blind” Pilot | By targeting radar and communications, the attacker forces the adversary’s leadership to fly “blind,” making decisions based on obsolete or fabricated data. 10 |

| 17 | Hyper-Legalism | Operations are now “legally encased” exercises; every kinetic action must be pre-justified by specific domestic and international legal frameworks. 18 |

| 18 | Insider Threat | The infiltration of the adversary’s inner circle (e.g., turning bodyguards or key generals) is a prerequisite for a zero-casualty extraction. 19 |

| 19 | Signal vs. Noise | A successful strategist increases the “entropy” (noise) in the adversary’s system, making it impossible for them to distinguish a feint from the main effort. 1 |

| 20 | Portable Precedent | The Venezuela model establishes a portable strategic precedent for “decapitation strategies” against other regimes labeled as criminal enterprises. 20 |

1. Introduction: The Death of the Binary Conflict Model

The traditional Western conception of war, historically characterized by a binary toggle between “peace” and “conflict,” has been rendered obsolete by the realities of the 21st-century security environment. In its place has emerged a continuous, undulating spectrum of engagement known as the “Gray Zone,” where state and non-state actors compete for strategic advantage using instruments that fall aggressively below the threshold of conventional military response.13 This evolution demands a radical restructuring of our analytical frameworks. We can no longer view conflicts as isolated events with clear beginnings and ends; rather, they are continuous cycles of shaping, destabilizing, and re-ordering systems.

The Venezuelan theater, culminating in the extraction of Nicolás Maduro in 2026, serves as the definitive case study for this new era. It represents the death of “Linear Warfare”—the idea that force is applied in a straight line against a defending force—and the birth of “Systemic Warfare.” In this model, the adversary is not treated as an army to be defeated, but as a system to be collapsed.

To understand the mechanics of modern regime change, we must integrate the ancient strategic philosophy of Sun Tzu with the 20th-century aerial combat theories of Colonel John Boyd. Sun Tzu teaches that the acme of skill is to “subdue the enemy without fighting” and to “attack the enemy’s strategy” before his army.5 Boyd extends this by introducing the OODA Loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act), arguing that victory comes from operating at a tempo that “folds” the adversary back inside themselves, generating confusion and disorder until their will to resist collapses.1

In the context of Venezuela, these theories were not abstract concepts discussed in war colleges. They were operationalized through a multi-year campaign of Lawfare (using indictments to delegitimize leadership), Economic Warfare (sanctions to degrade infrastructure), and Cognitive Warfare (manipulating perception to sever the regime’s support). The culmination of this was not a “war” in the Clausewitzian sense, but a “fast transient”—a sudden, decisive spike in entropy that shattered the regime’s control before it could effectively react.

2. Theoretical Architecture: The Sun Tzu-Boyd Synthesis

The integration of Sun Tzu’s eastern philosophy with Boyd’s western kinetic theory provides the necessary intellectual architecture to understand Operation Absolute Resolve. Both theorists focus not on the destruction of the enemy’s material, but on the destruction of the enemy’s mind and connections.

2.1 Sun Tzu: The Art of the Indirect Approach

Sun Tzu’s relevance to the 21st century lies in his emphasis on the interplay between “Cheng” (direct) and “Ch’i” (indirect) forces. In modern terms, the “Cheng” represents conventional military posturing—carrier strike groups, troop deployments, and public sanctions—that fixes the enemy’s attention. The “Ch’i” is the unseen strike—the cyberattack on a power grid, the sealed indictment, the turning of an insider.5

- Moral Law (The Tao): Sun Tzu argues that a ruler must be in harmony with his people. U.S. strategy against Maduro systematically attacked this “Moral Law” through information operations that highlighted corruption and starvation, thereby separating the leadership from the population and the military rank-and-file. The designation of the regime as a “Narco-Terrorist” entity was a direct assault on its Moral Law, stripping it of the legitimacy required to command loyalty.3

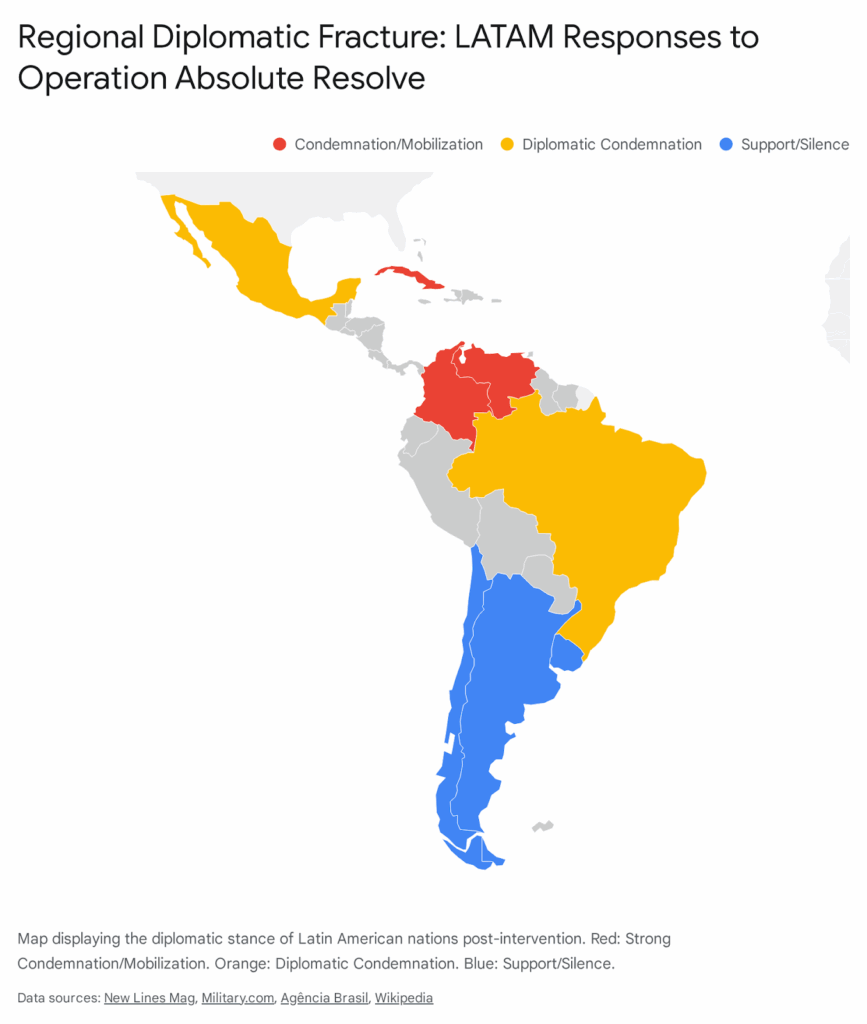

- Attacking Alliances: Before a kinetic strike, one must disrupt the enemy’s alliances. The U.S. diplomatic isolation of Venezuela effectively neutralized the ability of Russia and China to intervene meaningfully. By the time of the strike in 2026, Venezuela’s traditional patrons had been maneuvered into a position where physical intervention was politically or logistically impossible.17

2.2 John Boyd: Weaponizing Time and Entropy

Colonel John Boyd’s OODA Loop is frequently misunderstood as a simple decision cycle. In reality, it is a theory of entropy. Boyd posited that by executing actions faster than an adversary can process (Observe/Orient), a belligerent creates a “mismatch” between the adversary’s perception of the world and reality.2

- Destruction of Orientation: The “Orientation” phase is the most critical. It is where genetic heritage, cultural tradition, and previous experience filter information. Modern Cognitive Warfare targets this phase directly. By flooding the information space with conflicting narratives (Deepfakes, contradictory official statements), the attacker corrupts the adversary’s orientation, leading to flawed decisions.22 In Venezuela, the “fog of war” was induced not just by smoke, but by data—conflicting reports of troop movements and loyalties that froze the decision-making capability of the High Command.

- Isolation: Boyd argued that the ultimate aim is to isolate the enemy—mentally, morally, and physically. The 2026 operation achieved this by physically severing communications (Cyber/EW) and morally isolating the leadership through “Lawfare” branding.4

2.3 The Synthesis: The “Systemic Collapse” Doctrine

Combining these thinkers gives us a modern doctrine: Systemic Collapse. The goal is not the physical annihilation of the Venezuelan military (which would require a costly invasion) but the systemic collapse of its Command and Control (C2) and political cohesion.

- Mechanism: Use Economic Warfare to degrade the physical maintenance of defense systems (radar, jets) over years.9 Use Lawfare to create a “fugitive” psychology within the leadership.14 Use Cyber to blind the sensors at the moment of the strike.7

- Result: The adversary is defeated before the first shot is fired because they are blind, deaf, and paralyzed by internal paranoia.

3. The Seven-Phase Conflict Lifecycle Model

Traditional doctrine (JP 3-0) utilizes a six-phase model (Shape, Deter, Seize Initiative, Dominate, Stabilize, Enable Civil Authority).23 However, this model is insufficient for analyzing hybrid decapitation strategies which rely heavily on non-kinetic “pre-war” maneuvering. Based on the Venezuela case study and the integration of Boyd’s theories, we propose a more granular Seven-Phase Conflict Lifecycle. This model recognizes that the most decisive actions often occur long before “conflict” is officially recognized.

Phase I: Foundational Shaping (The Legal & Moral Baseline)

- Objective: Define the adversary as a criminal entity rather than a sovereign state to strip them of international protections (Westphalian sovereignty).

- Key Capabilities: Lawfare, Strategic Communications, Diplomacy.

- Case Analysis: The 2020 indictments of Maduro and 14 other officials for “narco-terrorism” were not merely legal acts; they were strategic shaping operations. By moving the conflict from the realm of “political dispute” to “transnational crime,” the U.S. created a portable legal framework that justified future extraction. This phase attacks the “Moral Law” by delegitimizing the leader in the eyes of the international community and, crucially, his own military subordinates.3

Phase II: Economic & Infrastructural Erosion

- Objective: Degrade the adversary’s physical capacity to maintain high-tech defense systems through resource starvation.

- Key Capabilities: Sanctions (OFAC), Export Controls, Financial Isolation.

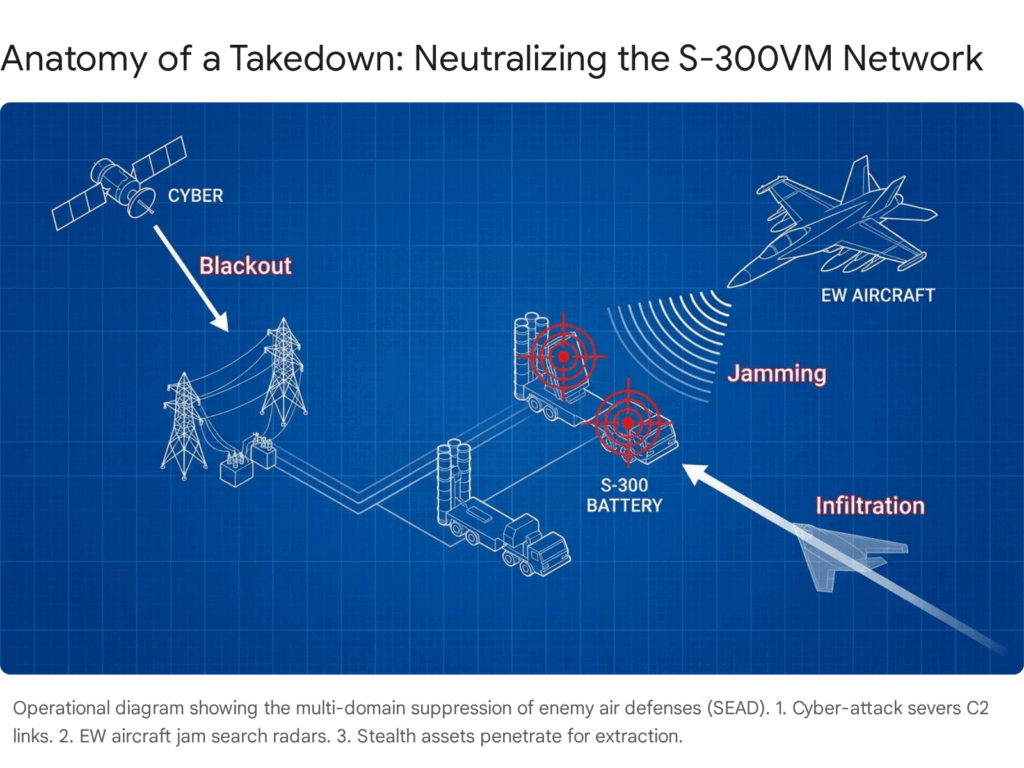

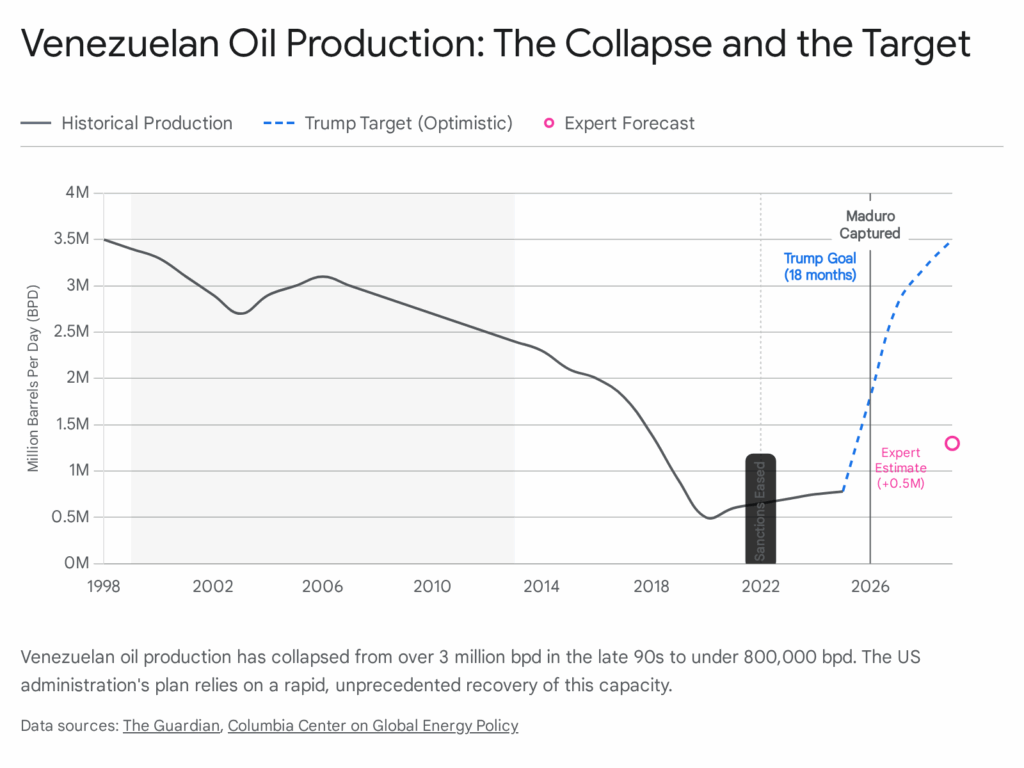

- Case Analysis: Years of sanctions on PDVSA (state oil) and the central bank led to a collapse in maintenance funding. By 2026, the Venezuelan air defense grid—comprised of formidable Russian S-300VM and Buk-M2 systems—suffered from a critical lack of spare parts and skilled operator training. The “Cheng” force of sanctions created the physical vulnerability that the “Ch’i” force (EW aircraft) would later exploit. This phase validates Boyd’s concept of increasing friction; the enemy machine simply ceases to function efficiently.9

Phase III: Intelligence Penetration (The “Glass House”)

- Objective: Achieve total information dominance to enable surgical action.

- Key Capabilities: HUMINT infiltration, SIGINT saturation, Pattern of Life analysis.

- Case Analysis: The infiltration of the regime’s security apparatus was total. Intelligence agencies built a “pattern of life” on Maduro, tracking details as minute as his pets and dietary habits.8 This phase creates a “Glass House” effect—the target knows they are watched, inducing paranoia. They begin to see threats everywhere, purging loyalists and disrupting their own chain of command. This self-cannibalization is a key goal of the psychological component of the OODA loop.19

Phase IV: Cognitive Destabilization (The “Ghost” Phase)

- Objective: Induce paranoia and fracture the inner circle’s loyalty through ambiguity.

- Key Capabilities: PsyOps, Deepfakes, Cyber probing, Rumor propagation.

- Case Analysis: This phase involves “Gray Zone” activities designed to test reactions and sow discord. The use of “Operation Tun Tun” by the regime—raiding homes of dissenters—was turned against them as U.S. ops fed false information about who was a traitor. The goal is to maximize entropy. When the regime cannot distinguish between a loyal general and a CIA asset, its ability to Decide (the ‘D’ in OODA) is paralyzed.25

Phase V: Pre-Kinetic Isolation (The “Blindness” Phase)

- Objective: Sever the adversary’s C2 and diplomatic lifelines immediately prior to the strike.

- Key Capabilities: Cyber Blockades, Diplomatic Ultimatums, Electronic Warfare positioning.

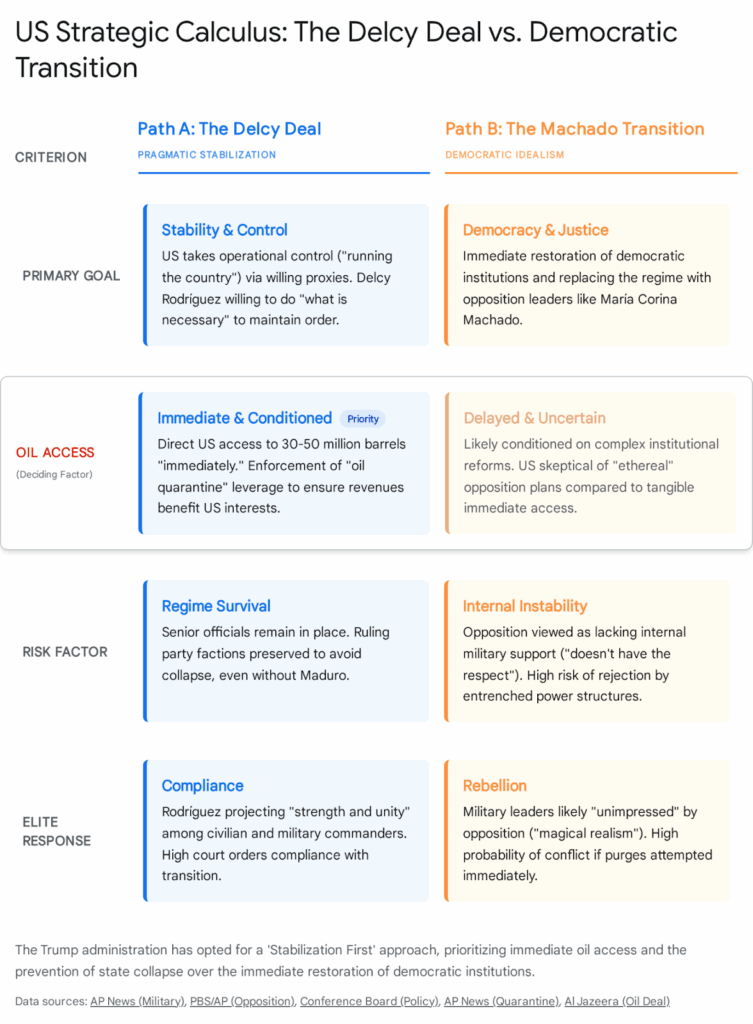

- Case Analysis: In the days leading up to Jan 3, 2026, the U.S. designated the situation as a “non-international armed conflict” with cartels, providing the final legal authorization.15 Simultaneously, cyber assets were positioned to disrupt the Guri Dam grid control systems. This phase corresponds to the “Isolation” in Boyd’s theory—stripping the enemy of their ability to communicate with the outside world or their own forces.6

Phase VI: The Kinetic Spike (The Decapitation)

- Objective: Execute the removal of the leadership node with maximum speed and minimum signature.

- Key Capabilities: Special Operations Forces (SOF), EW (Growlers), Precision Air Support.

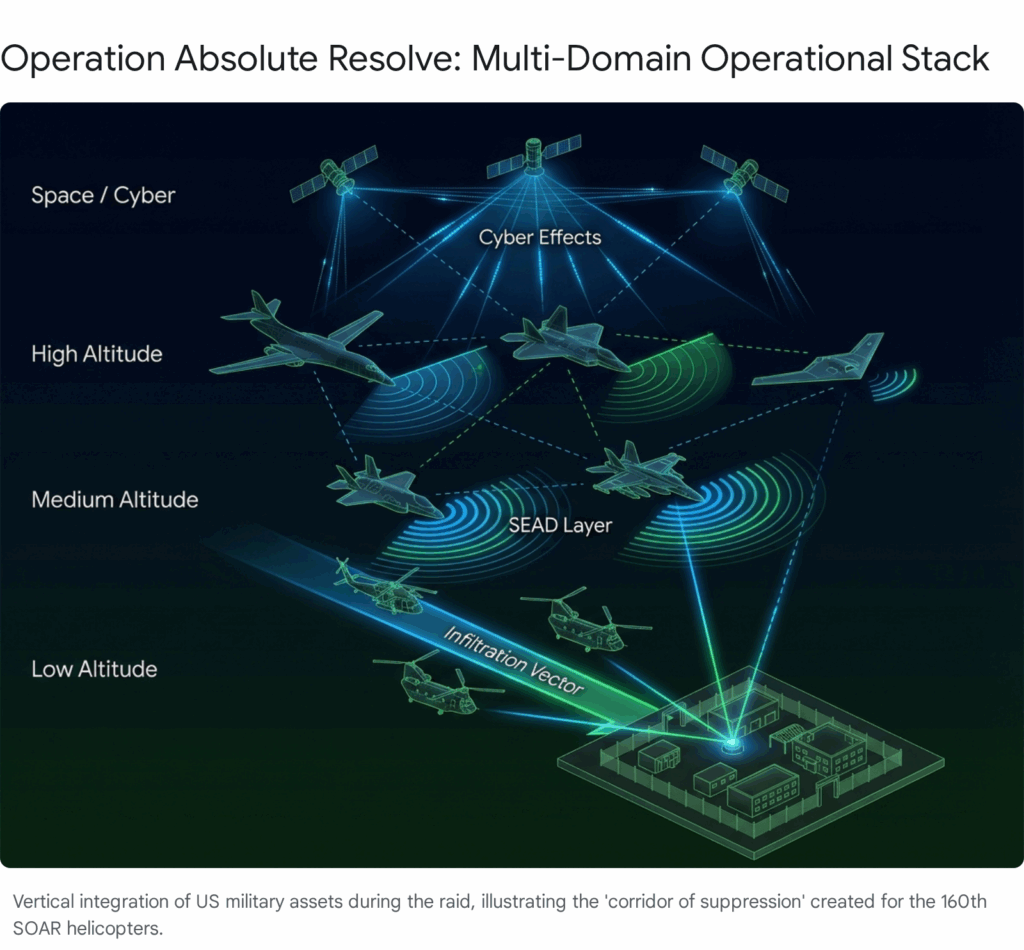

- Case Analysis: Operation Absolute Resolve. A surgical raid involving 200+ operators. Key to success was the EA-18G Growler support which jammed the remaining functional radars, and the cyber-induced blackout (“lights of Caracas turned off”) which added physical confusion to the tactical environment. This was the “Fast Transient”—a maneuver so rapid the adversary could not Orient to it until it was over.10

Phase VII: Strategic Consolidation (The New Status Quo)

- Objective: Normalize the new reality through legal processing and political transition.

- Key Capabilities: Lawfare (Trials), Diplomatic Recognition, Economic Reconstruction.

- Case Analysis: The immediate transfer of 50 million barrels of oil and the processing of Maduro in the Southern District of New York (SDNY) solidified the “Law Enforcement” narrative. The lifting of sanctions acted as the carrot for the remaining military structure to comply, effectively buying the loyalty of the surviving apparatus.6

4. Case Study Analysis: Operation Absolute Resolve (2026) vs. Operation Gideon (2020)

A comparative analysis of the failed 2020 coup attempt and the successful 2026 operation reveals the critical importance of “Layered Capabilities” and “Operational Security.” It serves as a stark lesson in the difference between a mercenary adventure and a state-backed multi-domain operation.

4.1 Anatomy of Failure: Operation Gideon (2020)

Operation Gideon serves as a textbook example of how not to conduct a decapitation strike. It failed not because of a lack of bravery, but because of a catastrophic failure in the “Observe” and “Orient” phases of the planning cycle.

- Intelligence Leakage: The operation was infiltrated by Venezuelan intelligence (SEBIN) months in advance. The planners operated in a permissive information environment, unaware that their “secret” meetings were being monitored.

- The Encryption Fallacy: The planners relied on commercial encrypted applications like WhatsApp and Signal, believing them to be secure against state-level actors. This was a fatal error. Poor tradecraft—such as including unknown members in group chats—allowed the adversary to map the entire network.11

- Adversarial Control: The regime was so deeply inside the plotters’ OODA loop that Diosdado Cabello was able to broadcast details of the plot on national television before it launched. The adversary controlled the tempo entirely.27

4.2 Anatomy of Success: Operation Absolute Resolve (2026)

In contrast, Operation Absolute Resolve was characterized by “Intelligence Dominance” and “Layered Ambiguity.”

- Pattern of Life: The NSA and NGA utilized advanced surveillance to build a granular “pattern of life” on the target. This went beyond location tracking; it understood the target’s psychology, routines, and vulnerabilities.8

- Secure Communications: Learning from the “Signal trap” of 2020, the 2026 operation utilized proprietary military networks and distinct compartmentalization, ensuring that no single leak could compromise the whole.

- Multi-Domain Integration: Unlike the purely kinetic Gideon, Absolute Resolve integrated cyber effects (grid shutdown) and electronic warfare (radar jamming) to create a permissive environment for the kinetic force.

4.3 Summary of Operational Variables

The following table contrasts the key operational variables that determined the divergent outcomes of the two operations.

| Operational Variable | Operation Gideon (2020) | Operation Absolute Resolve (2026) |

| Primary Domain | Kinetic (Amphibious/Light Infantry) | Multi-Domain (Cyber, EW, Space, Kinetic) |

| Legal Framework | Private Contract (Silvercorp) | Federal Indictment / Armed Conflict Designation |

| Intelligence Status | Compromised (Infiltrated by SEBIN) | Dominant (Pattern of Life established) |

| Cyber Support | None | Grid Disruption / C2 Severing |

| Communications | Commercial Apps (Signal/WhatsApp) | Proprietary Military Networks |

| Outcome | Mission Failure / Mass Arrests | Mission Success / Target Captured |

| Boyd’s OODA Status | U.S. trapped in Enemy’s Loop | Enemy trapped in U.S. Loop |

5. Domain Analysis: The Pillars of Modern Conflict

The success of modern conflict operations relies on the seamless integration of distinct domains. In the Venezuelan case, three domains stood out as decisive: Legal, Economic, and Cyber/EW.

5.1 The Legal Domain: Weaponized Indictments (Lawfare)

Lawfare has evolved from a method of dispute resolution to a primary weapon of war. The 2020 indictments against the Venezuelan leadership were strategic artillery.

- Mechanism: By labeling the state leadership as “Narco-Terrorists,” the U.S. effectively removed the shield of sovereign immunity. This legal categorization allowed the Department of Defense to coordinate with the Department of Justice, treating the 2026 raid not as an act of war against a nation, but as a police action against a criminal enterprise.3

- Impact: This reduces the political cost of the operation. It is easier to sell an “arrest” to the international community than a “coup.” It also creates a “fugitive mindset” in the target, who knows that their status is permanently compromised regardless of borders.

5.2 The Economic Domain: Sanctions as Artillery

Economic warfare is often viewed as a tool of punishment, but strategically, it is a tool of attrition.

- Mechanism: The long-term sanctions regime against Venezuela did more than starve the population; it starved the military machine. Modern air defense systems like the S-300 require constant, expensive maintenance. By cutting off access to global financial markets and specific high-tech imports, the U.S. ensured that by 2026, the Venezuelan radar network was operating at a fraction of its capacity.9

- Impact: When the EA-18G Growlers arrived, they were jamming a system that was already degrading. The “kill” was achieved years prior in the Treasury Department.

5.3 The Cyber/EW Domain: The Invisible Breaching Charge

The Cyber and Electronic Warfare domains acted as the “breaching charge” that opened the door for the kinetic force.

- The Blackout: The disruption of the Caracas power grid was a psychological and tactical masterstroke. Psychologically, it signaled to the population and the regime that they had lost control of their own infrastructure. Tactically, it degraded the ability of the military to communicate and coordinate a response. A darkened city is a terrifying environment for a defending force that relies on centralized command.6

- The Growler Effect: The use of EA-18G Growlers to jam radars created a “corridor of invisibility” for the transport helicopters. This capability renders the adversary’s expensive air defense investments worthless, turning their “eyes” into sources of noise and confusion.10

6. Strategic Implications for Great Power Competition

The success of Operation Absolute Resolve establishes a “Portable Decapitation Model” that has profound implications for global security, particularly for revisionist powers like China, Russia, and Iran.

6.1 The China Question: Radar Vulnerability

The decapitation strike sends a potent, chilling signal to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Venezuela’s air defense network was heavily reliant on Chinese and Russian technology. The failure of these systems to detect or stop the U.S. infiltration exposes a critical vulnerability in Chinese military hardware.17

- Insight: If the U.S. can blind Venezuelan S-300s and Chinese radars, can they do the same over the Taiwan Strait? This creates “doubt” in the PLA’s OODA loop. It forces them to question the reliability of their own sensor networks, potentially delaying their own aggressive timelines as they re-evaluate their technological resilience. The “perception” of vulnerability is as damaging as the vulnerability itself.

6.2 The Russian Response: Hybrid Defense

Russia will likely view this operation as a validation of its fears regarding U.S. “Color Revolution” tactics. We can expect a shift toward “de-centralized command” in authoritarian regimes. If the leader can be removed surgically, regimes will move toward committee-based leadership structures or AI-driven “dead hand” systems to ensure regime survival even after a decapitation strike.29 This forces the U.S. to update the model from “Decapitation” (removing the head) to “Systemic Disintegration” (removing the nervous system).

6.3 The Future of Sovereignty

The operation solidifies a new norm in international relations: Sovereignty is conditional. The designation of a state as a “criminal enterprise” or “narco-terrorist state” effectively nullifies the protections of Westphalian sovereignty in the eyes of the intervenor. This “Hyper-Legalism”—where kinetic actions are encased in complex domestic and international legal justifications—will become the standard for future interventions.18 Nations in the “Global South” will increasingly view U.S. counter-terrorism partnerships with suspicion, fearing that the legal framework built for cooperation today could be the warrant for invasion tomorrow.

7. Conclusion

The 2026 extraction of Nicolás Maduro was not a victory of firepower, but of synchronization. It demonstrated that in the modern era, the “war” is fought and won in the years prior to the kinetic event—in the courtrooms of the Southern District of New York, the server farms of Cyber Command, and the banking terminals of the Department of the Treasury.

By applying the lenses of Sun Tzu and Boyd, we see that the U.S. successfully “attacked the strategy” of the Maduro regime. They attacked its legitimacy (Lawfare), its sight (Cyber/EW), and its resources (Sanctions). When the helicopters finally landed in Caracas, they were merely the final punctuation mark on a sentence that had been written years in advance.

The lesson for future conflict is clear: The victor will be the side that can best integrate diverse domains—legal, economic, cyber, and kinetic—into a single, coherent “OODA Loop” that processes reality faster than the opponent can comprehend it. The era of the “General” is over; the era of the “System Architect” has begun.

Appendix A: Methodology

This report was compiled using a multi-disciplinary approach, synthesizing open-source intelligence (OSINT), military doctrine (JP 3-0, JP 5-0), and strategic theory.

- Source Material: Analysis was based on a dataset of 59 research snippets covering the period from 2018 to 2026, including government indictments, post-action reports from Operation Absolute Resolve, and academic analyses of Gray Zone warfare.

- Theoretical Application: The analysis applied the “Strategic Theory” lens, specifically mapping historical texts (Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, Boyd’s A Discourse on Winning and Losing) onto modern operational facts to derive second-order insights.

- Conflict Modeling: The “Seven-Phase Lifecycle” was derived inductively by reverse-engineering the timeline of U.S. actions against Venezuela from 2020 to 2026, identifying distinct phases of escalation that differ from standard doctrine.

- Limitations: The analysis relies on public accounts of classified operations (Cyber Command activities) and may not reflect the full extent of covert capabilities. The interpretation of “intent” is inferred from operational outcomes.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- Colonel John Boyds Thoughts on Disruption – Marine Corps University, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.usmcu.edu/Outreach/Marine-Corps-University-Press/MCU-Journal/JAMS-vol-14-no-1/Colonel-John-Boyds-Thoughts-on-Disruption/

- Synthesizing Strategic Frameworks for Great Power Competition – Marine Corps University, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.usmcu.edu/Portals/218/JAMS_Fall%202025_16_2_Holtz.pdf

- Inside the Legal Battles Ahead for Nicolás Maduro – Lawfare, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/inside-the-legal-battles-ahead-for-nicolas-maduro

- Venezuela—Indictments, Invasions, and the Constitution’s Crumbling Guardrails | Cato at Liberty Blog, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.cato.org/blog/indictments-invasions-constitutions-crumbling-guardrails

- Sun Tzu and the Art of Cyberwar | www.dau.edu, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.dau.edu/library/damag/january-february2018/sun-tzu-and-art-cyberwar

- Layered Ambiguity: US Cyber Capabilities in the Raid to Extract …, accessed January 26, 2026, https://my.rusi.org/resource/layered-ambiguity-us-cyber-capabilities-in-the-raid-to-extract-maduro-from-venezuela.html

- Cyberattacks Likely Part of Military Operation in Venezuela – Dark Reading, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.darkreading.com/cybersecurity-operations/cyberattacks-part-military-operation-venezuela

- US spy agencies contributed to operation that captured Maduro – Defense One, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.defenseone.com/threats/2026/01/us-spy-agencies-contributed-operation-captured-maduro/410437/

- A Primer on 21st-Century Economic Weapons | Lawfare, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/a-primer-on-21st-century-economic-weapons

- How Defense Tech Enabled the US Operation to Capture Nicolás Maduro – ExecutiveGov, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.executivegov.com/articles/defense-tech-nicolas-maduro-capture-isr-cyber

- United States government group chat leaks – Wikipedia, accessed January 26, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_government_group_chat_leaks

- When Secure Messaging Fails: What the Signal Scandal Taught Us – MailGuard, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.mailguard.com.au/partner-blog/when-secure-messaging-fails-what-the-signal-scandal-taught-us

- Gray zone warfare part 4: Gray zone deterrence – Talbot West, accessed January 26, 2026, https://talbotwest.com/industries/defense/gray-zone-warfare/deterrence-doctrine-for-the-gray-zone

- What are the implications of the US intervention in Venezuela for organized crime? | Global Initiative, accessed January 26, 2026, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/what-are-the-implications-of-the-us-intervention-in-venezuela-for-organized-crime/

- U.S. Capture of Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro: Considerations for Congress, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IN12618

- Imagery from Venezuela Shows a Surgical Strike, Not Shock and Awe, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.csis.org/analysis/imagery-venezuela-shows-surgical-strike-not-shock-and-awe

- What does the US raid in Venezuela mean for China’s designs on Taiwan? – The Guardian, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/06/what-us-action-in-venezuela-means-for-taiwan

- Legal Deterrence by Denial: Strategic Initiative and International Law in the Gray Zone, accessed January 26, 2026, https://tnsr.org/2025/06/legal-deterrence-by-denial-strategic-initiative-and-international-law-in-the-gray-zone/

- MAGA, the CIA, and Silvercorp: The Bizarre Backstory of the World’s Most Disastrous Coup, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.vice.com/en/article/maga-the-cia-and-silvercorp-the-bizarre-backstory-of-the-worlds-most-disastrous-coup/

- America’s Invasion of Venezuela: Strike of the New Global Disorder – The Elephant, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.theelephant.info/opinion/2026/01/08/americas-invasion-of-venezuela-strike-of-the-new-global-disorder/

- OODA Loop: A Blueprint for the Evolution of Military Decisions – RTI, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.rti.com/blog/ooda-loop-a-blueprint-for-the-evolution-of-military-decisions

- Cognitive warfare – Wikipedia, accessed January 26, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_warfare

- Gray Is the New Black: A Framework to Counter Gray Zone Conflicts …, accessed January 26, 2026, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/2556217/gray-is-the-new-black-a-framework-to-counter-gray-zone-conflicts/

- How U.S. Sanctions on Venezuela Escalated in the Lead-Up to Maduro’s Capture – Kharon, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.kharon.com/brief/us-venezuela-trump-nicolas-maduro-capture-sanctions

- venezuela – Organization of American States, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.oas.org/fpdb/press/Report_2025.pdf

- Operation Absolute Resolve: A Detailed Analysis – SOF Support …, accessed January 26, 2026, https://sofsupport.org/operation-absolute-resolve-anatomy-of-a-modern-decapitation-strike/

- Operation Gideon (2020) | Military Wiki | Fandom, accessed January 26, 2026, https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/Operation_Gideon_(2020)

- Operation Gideon (2020) – Wikipedia, accessed January 26, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Gideon_(2020)

- Decapitation Strategy in Caracas: The Logic, Timing, and Consequences of the U.S. Operation in Venezuela – Robert Lansing Institute, accessed January 26, 2026, https://lansinginstitute.org/2026/01/03/decapitation-strategy-in-caracas-the-logic-timing-and-consequences-of-the-u-s-operation-in-venezuela/