The period spanning 2021 through early 2026 marks one of the most transformative eras in the history of United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) small arms acquisition. Driven by the strategic imperative to reassert overmatch against near-peer adversaries in Great Power Competition (GPC), the Command has systematically dismantled its reliance on legacy NATO calibers—specifically 5.56x45mm and 7.62x51mm—in favor of optimized intermediate and precision cartridges. This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the contracting activities, requirements development, and industrial base maneuvers that have defined this modernization effort. The overarching theme of this half-decade is the pursuit of “lethality extension,” a doctrinal shift aimed at pushing the effective engagement envelope of the individual operator beyond the capabilities of peer competitors equipped with standard-issue weaponry.

From a contracting perspective, the last five years have been characterized by a distinct bifurcation in the industrial base. On one side, Sig Sauer has emerged as a “super-prime” supplier for the Command, securing dominance in the Personal Defense Weapon (PDW) sector, the Suppressed Upper Receiver Group (SURG) program, and the medium machine gun category. On the other side, USSOCOM has demonstrated a remarkable willingness to engage with agile, specialized manufacturers for its core infantry systems. This is best exemplified by the landmark selection of LMT Defense in August 2025 for the $92 million Medium Range Gas Gun-Assault (MRGG-A) contract, and the surprise selection of Sons of Liberty Gun Works (SOLGW) in November 2025 for the Combat Assault Rifle (CAR). These awards signal a departure from the “lowest price technically acceptable” model toward a “best value” approach that prizes technical superiority and manufacturing agility.

The modernization portfolio is anchored by the adoption of the 6.5mm Creedmoor (6.5 CM) as the primary cartridge for the next generation of assault and sniper support weapons. This ballistic transition was solidified by a $40 million ammunition contract awarded to Black Hills Ammunition in August 2025, ensuring that the logistical tail matches the operational tooth of the new weapon systems. Simultaneously, the contracting landscape has witnessed strategic recalibrations, most notably the abrupt cancellation of the Lightweight Machine Gun-Assault (LMG-A) prototyping effort in December 2025, a move that reflects the complex interplay between internal SOF requirements and the broader service pressures introduced by the U.S. Army’s Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW) program.

Critical enablers have not been neglected. Nightforce Optics secured a massive $17.6 million contract for the Precision-Variable Power Scope (P-VPS), cementing the shift toward high-magnification optics on standard infantry rifles. SureFire and Sig Sauer continue to dominate signature reduction, with suppression transitioning from a specialized capability to a universal requirement for all fielded systems. The following table summarizes the strategic timeline of these major acquisition milestones, illustrating the concurrent development of precision, maneuver, and support capabilities.

| Timeframe | Program / Milestone | Contractor | Key Details |

| 2021–2022 | ASR Fielding | Barrett Firearms | Full Rate Production of MK22 (MRAD) commences. |

| Sep 2022 | PDW Award | Sig Sauer | Award for MCX Rattler (.300 BLK). Initial $5M ceiling. |

| Late 2023 | MRGG-Sniper Award | Geissele Automatics | Selection of Mk1 Mod 0 (6.5 CM) for sniper support. |

| 2023–2024 | LMG-M Fielding | Sig Sauer | Operational fielding of MG 338 (.338 NM) via OTA. |

| Aug 2025 | MRGG-Assault Award | LMT Defense | $92M IDIQ for 14.5″ 6.5 CM Carbine. |

| Aug 2025 | 6.5 CM Ammo Award | Black Hills Ammo | $40M IDIQ for match-grade combat ammunition. |

| Nov 2025 | CAR Award | SOLGW | Selection of MK1 (5.56mm) for specialized assault role. |

| Dec 2025 | LMG-A Cancellation | N/A | Prototyping effort canceled; responsibility shifted to Navy Crane. |

This report details the technical specifications, contract mechanisms, and operational implications of each major award, offering a comprehensive view of the USSOCOM small arms arsenal as it stands in 2026.

1. Strategic Context: The Doctrine of Overmatch

To understand the procurement decisions of the last five years, one must first analyze the doctrinal vacuum they were designed to fill. For two decades, USSOCOM operations were defined by the Global War on Terror (GWOT), predominantly Close Quarters Battle (CQB) in urban environments against adversaries with limited ballistic protection and rudimentary small arms. In this environment, the Mk18 (10.3-inch 5.56mm carbine) and the MP7 (4.6mm PDW) were supreme. However, the 2018 National Defense Strategy signaled a pivot to Great Power Competition, placing US forces in potential conflict with near-peer state actors equipped with modern body armor and weapons capable of engaging effectively out to 600 meters and beyond.

1.1 The Ballistic Deficit

Analysis conducted by the US Army and USSOCOM identified a critical “ballistic deficit” in the standard 5.56mm NATO cartridge. While lethal at close range, the 5.56mm (specifically the M855A1) loses the ability to defeat Level IV ceramic body armor at relatively short distances. Furthermore, the maximum effective range of the M4A1 is generally cited as 500 meters for a point target. Adversary systems utilizing the 7.62x54R cartridge, particularly when modernized, allowed threat forces to out-range US operators, suppressing them from distances where return fire was ineffective.

The initial response to this was the Interim Combat Service Rifle (ICSR) program, a short-lived attempt to field a 7.62x51mm battle rifle. However, the 7.62 NATO round, while possessing greater range, imposes severe weight penalties on the operator and ammunition loadout, and its recoil impulse makes rapid follow-up shots in CQB difficult. USSOCOM required a “Goldilocks” solution: a cartridge with the recoil profile and weight closer to 5.56mm, but with terminal ballistics and effective range exceeding 7.62mm.

1.2 The Divergence from “Big Army”

It is critical to note that USSOCOM and the U.S. Army identified the same problem but arrived at fundamentally different solutions. The Army pursued the Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW), selecting the 6.8x51mm (.277 Fury) cartridge. This round utilizes a high-pressure, hybrid-metallic case to drive a projectile at extreme velocities to penetrate armor plates at distance. The trade-off is a heavier weapon, significantly higher chamber pressure (80,000 psi), and increased recoil.

USSOCOM, operating with different logistical constraints and mission profiles, prioritized precision and signature reduction over raw barrier penetration. The Command assessed that special operators rely on maneuver and accuracy to defeat threats rather than brute-force armor piercing. Consequently, USSOCOM selected the 6.5mm Creedmoor (6.5 CM). Originally a commercial precision rifle cartridge, the 6.5 CM offers an exceptionally high ballistic coefficient, allowing it to remain supersonic beyond 1,200 meters. It achieves this performance with standard chamber pressures compatible with existing AR-10/SR-25 platform architecture, allowing for lighter, more familiar weapons systems. This strategic divergence defines every major rifle contract awarded by USSOCOM between 2021 and 2026.

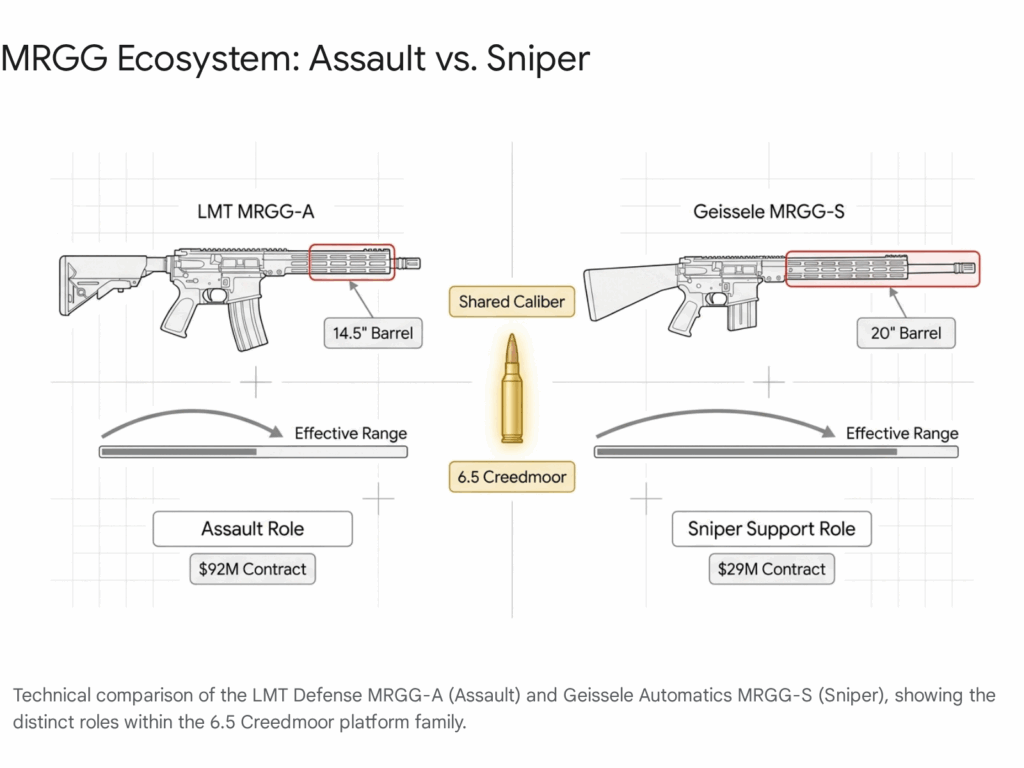

2. The Mid-Range Gas Gun (MRGG) Program

The flagship of USSOCOM’s modernization effort is the Mid-Range Gas Gun (MRGG) program. This initiative was not merely a rifle replacement; it was a conceptual restructuring of the sniper and designated marksman roles. The program was bifurcated into two distinct lines of effort: the MRGG-Sniper (MRGG-S) and the MRGG-Assault (MRGG-A). This bifurcation acknowledges that a single “one-size-fits-all” rifle, even with a versatile caliber like 6.5 CM, cannot optimally serve both the dedicated sniper team and the assaulting rifleman.

2.1 MRGG-Assault (MRGG-A): The LMT Defense Award

On August 20, 2025, the Department of Defense announced that Lewis Machine & Tool Company (LMT Defense) had secured the MRGG-A contract.1 The contract (H9240325DE003) is an Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) vehicle with a maximum ceiling of $92,000,000, with an ordering period extending through August 2035.

Technical Analysis of the LMT Solution

The selection of LMT Defense validates the operational superiority of the Monolithic Rail Platform (MRP). Unlike standard AR-pattern rifles where the handguard is screwed onto the barrel nut, the LMT MRP upper receiver is forged and milled from a single piece of aerospace-grade aluminum. The handguard and receiver are one continuous unit. This architecture offers two distinct advantages critical to USSOCOM requirements:

- Zero Retention for Enablers: Modern night fighting relies heavily on rail-mounted lasers (like the NGMC) and clip-on thermal imagers. Any flex or rotation in a traditional handguard shifts the aiming point of these devices. The monolithic upper is completely rigid, ensuring that the laser’s zero matches the barrel’s point of impact under all conditions.

- Barrel Interchangeability: The MRP system allows the operator to change barrels in roughly one minute using a simple torque wrench, without losing the zero of the primary optic. This capability is central to the MRGG-A concept, which requires the rifle to convert between 6.5 CM (for combat) and 7.62x51mm (for training or indigenous ammunition compatibility).3

The MRGG-A features a 14.5-inch barrel, a length optimized to balance the ballistic potential of the 6.5 CM cartridge with the maneuverability required for CQB. It is a select-fire weapon, capable of fully automatic fire, distinguishing it from the semi-automatic-only sniper variants. The $92 million ceiling indicates that USSOCOM intends to field this weapon broadly across the Special Forces Groups, Ranger Regiment, and Naval Special Warfare elements, potentially replacing the Mk17 SCAR-H in the battle rifle role.

2.2 MRGG-Sniper (MRGG-S): The Geissele Automatics Award

While LMT secured the assault variant, the precision-focused MRGG-S contract was awarded to Geissele Automatics in late 2023.4 Designated the Mk1 Mod 0, this contract carries a value of approximately $29 million.

The Geissele MRGG-S differs from the LMT variant primarily in barrel length and gas system tuning. It features a 20-inch barrel to squeeze maximum velocity from the 6.5 CM cartridge, extending the supersonic transition range well beyond 1,200 meters. The weapon is designed to serve as a Sniper Support Rifle (SSR), replacing the Mk20 SSR and the M110 SASS.

A critical innovation in the Geissele submission was its “Endurance” barrel technology and gas system optimized for full-time suppressed fire. Traditionally, gas-operated precision rifles suffer from “gas blowback” and erratic bolt velocities when run with a suppressor 100% of the time. Geissele’s engineering focused on regulating this backpressure to ensure that the weapon cycles smoothly and maintains sub-MOA (Minute of Angle) accuracy even after high round counts, a notorious weak point of previous SASS platforms.

The coexistence of these two platforms creates a complementary ecosystem: the sniper team utilizes the 20-inch Geissele for extreme precision, while the assaulters and flankers utilize the 14.5-inch LMT for maneuver warfare, both sharing the same 6.5 CM ammunition supply chain.

3. Personal Defense Weapons and Specialized Carbines

While the MRGG program extends the reach of the operator, the Personal Defense Weapon (PDW) and Combat Assault Rifle (CAR) programs address the requirements for concealment and close-range dominance. These contracts highlight USSOCOM’s focus on “low-visibility” operations, where operators must blend into local environments or operate from non-standard vehicles without the overt signature of a full-sized rifle.

3.1 Personal Defense Weapon (PDW): The Sig Sauer Rattler

In September 2022, USSOCOM awarded Sig Sauer a five-year, firm-fixed-price IDIQ contract (H9240322D0005) for the PDW, later identified as the Reduced Signature Assault Rifle (RSAR).6 Initially valued at $5 million, the contract ceiling was subsequently increased to $17 million in July 2023.8

The selected platform is the Sig MCX Rattler, a derivative of the MCX Virtus system featuring a short-stroke gas piston and a monolithic upper receiver. The defining feature of the Rattler is its 5.5-inch barrel and folding stock, allowing the weapon to be concealed in a small backpack or under a jacket—a capability impossible with the buffer-tube dependent M4 architecture.

The contract specifies the delivery of weapons in both .300 AAC Blackout (.300 BLK) and 5.56x45mm. The.300 BLK is the primary operational cartridge; when paired with the specified Sig SL-series suppressors, it allows for subsonic fire that is quieter than an MP5SD but delivers significantly more terminal energy. The July 2023 modification notably added 7.62x39mm conversion kits to the contract.8 This addition is strategically revealing: it allows USSOCOM operators to utilize battlefield-captured ammunition (AK-47/AKM pattern) while retaining the ergonomics and optics readiness of a modern western platform, a critical capability for sustained operations behind enemy lines where resupply is impossible.

3.2 Combat Assault Rifle (CAR): The SOLGW Mk1

In a significant divergence from the trend of awarding contracts to large defense primes, USSOCOM selected Sons of Liberty Gun Works (SOLGW) for the Combat Assault Rifle (CAR) program in November 2025.9 The award followed a rigorous competitive evaluation that subjected candidate rifles to extreme environmental stress testing, including heat, cold, dust, mud, and saltwater immersion.

The selected weapon is the SOLGW MK1, a select-fire AR-15 platform featuring an 11.5-inch barrel. Unlike the piston-driven Sig Rattler or the monolithic LMT MRGG, the SOLGW MK1 utilizes a traditional Direct Impingement (DI) gas system. While piston systems are often touted for cleanliness, DI systems are lighter, have fewer moving parts, and typically offer a smoother recoil impulse which translates to faster follow-up shots.

The selection of SOLGW, a company known in the commercial market for its obsessive quality control and adherence to “Mil-Spec plus” standards, signals a shift in USSOCOM’s acquisition philosophy. It suggests that for the dedicated 5.56mm CQB role, the Command values the refined execution of a proven design (the AR-15) over novel operating mechanisms. The CAR is likely intended to supplement or replace the Mk18 Mod 1 in specific direct-action units that prefer the ergonomics and weight balance of a DI gun over the heavier piston alternatives.

4. Machine Guns: Innovation and Recalibration

The machine gun sector has witnessed the most dramatic highs and lows of the last five years, characterized by the successful fielding of a new medium-caliber capability and the abrupt cancellation of the light-caliber assault program.

4.1 Lightweight Machine Gun-Medium (LMG-M): The.338 Revolution

The LMG-M program represents a successful effort to bridge the capability gap between the 7.62mm M240B/L and the.50 caliber M2HB. USSOCOM identified that existing medium machine guns lacked the effective range to engage targets beyond 1,100 meters, while heavy machine guns were too heavy for dismounted patrols. The solution was the .338 Norma Magnum (.338 NM) cartridge.

Sig Sauer has effectively monopolized this new category. Following safety certification in 2020, Sig began delivering the MG 338 (operational designation SL MAG) to USSOCOM under Other Transaction Agreements (OTAs) for combat evaluation and fielding.11 The MG 338 weighs approximately 21 pounds—lighter than the M240B—yet fires a projectile that remains supersonic past 1,500 meters and delivers significantly higher kinetic energy.

This program fundamentally alters the geometry of the infantry squad. A machine gunner equipped with an MG 338 can now effectively suppress or destroy light vehicles and structural targets at ranges previously requiring Javelin missiles or Close Air Support (CAS). The fielding of this system has continued through 2024 and 2025, with units integrating the weapon alongside the new 6.5 CM rifle fleet.

4.2 Lightweight Machine Gun-Assault (LMG-A): The Cancellation

In stark contrast to the success of the LMG-M, the Lightweight Machine Gun-Assault (LMG-A) program faced a sudden termination. On December 7, 2025, USSOCOM announced the cancellation of the LMG-A prototyping effort, stating that the SOF AT&L-KR office would no longer move forward with the project.13

The LMG-A was intended to replace the 5.56mm Mk46 and 7.62mm Mk48 belt-fed machine guns, which have been in service since the early years of the GWOT. The cancellation notice indicated that the effort would be transferred to the Navy Crane Contracting Office to be “restarted.”

This cancellation likely stems from two converging factors:

- The Caliber Conundrum: The US Army’s adoption of the XM250 (Sig MG 6.8) in 6.8x51mm creates a logistical conflict. If USSOCOM were to adopt a new 6.5 CM belt-fed machine gun (as LMT and others proposed), it would further bifurcate the supply chain from the conventional Army. Pausing the program allows USSOCOM to evaluate the maturity of the Army’s XM250 and determine if a 6.5 CM conversion of that platform is more viable than a unique commercial solution.

- Performance Margins: The existing Mk48 Mod 1 is a highly capable weapon. Industry analysts suggest that the submitted prototypes for the LMG-A may not have offered a sufficient leap in reliability or weight reduction to justify the cost of a full fleet replacement, particularly when funds were urgently needed for the MRGG and LMG-M programs.

5. Precision Sniper Systems: The Advanced Sniper Rifle (ASR)

While the MRGG-S handles the semi-automatic sniper support role, the dedicated bolt-action sniper capability has been consolidated under the Advanced Sniper Rifle (ASR) program. Awarded to Barrett Firearms for the MK22 (MRAD) system, this contract continues to see significant activity.

In early 2024, Barrett received a $14.2 million modification to its existing contract (H92403-19-D-0002) to produce MK22 systems and.338 barrel kits.15 The MK22 is a multi-caliber chassis system that allows the user to swap calibers at the user level. The primary operational calibers are:

- .338 Norma Magnum: For anti-personnel and anti-materiel engagement out to 1,500+ meters.

- .300 Norma Magnum: Optimized for extreme range anti-personnel precision.

- 7.62x51mm: For urban environments and low-cost training.

The ASR program has achieved Full Operational Capability (FOC) during this period. It represents a massive logistical simplification, replacing the M2010 (.300 Win Mag), the Mk13 (.300 Win Mag), and the M107 (.50 BMG) with a single air-transportable case.

6. Ammunition: The Vital Enabler

The introduction of the MRGG-A/S and LMG-M is predicated on the availability of high-quality ammunition. Unlike the 5.56mm/7.62mm stockpiles which are produced by the massive Lake City Army Ammunition Plant, the specialized SOF calibers require precision manufacturing.

On August 20, 2025, the same day as the LMT MRGG award, the Department of Defense awarded a $40,000,000 firm-fixed-price IDIQ contract to Black Hills Ammunition.16 This contract is specifically for the production of 6.5mm Creedmoor ammunition (DODIC AC58).

Black Hills is legendary in the special operations community for developing the Mk262 Mod 0/1 5.56mm cartridge, which significantly improved the lethality of the Mk12 SPR and M4A1. The award of the 6.5 CM contract to Black Hills rather than a mass-production entity like Olin/Winchester signals that USSOCOM views the 6.5 CM as a “match” cartridge that must maintain sniper-grade consistency (sub-MOA accuracy) even when fired from assault rifles. This contract ensures the ammunition supply will sustain the MRGG fleet through 2030.

7. Optics and Fire Control

The lethality of the new rifles is realized through advanced optics. The Miniature Aiming Systems – Day Optic (MAS-D) program has driven the acquisition of variable power scopes that combine the speed of a red dot with the magnification of a sniper scope.

In September 2022, Nightforce Optics (Lightforce USA) was awarded a $17.6 million IDIQ contract (H9240322D0009) for the Precision-Variable Power Scope (P-VPS).18 The selected optics are the ATACR 5-25x56mm F1 and ATACR 7-35x56mm F1. These are First Focal Plane (FFP) optics utilizing the Horus TREMOR3 reticle, which provides a grid for rapid wind and elevation holds without touching the turrets.

Simultaneously, the Squad-Variable Power Scope (S-VPS) component has fielded Low Power Variable Optics (LPVOs), primarily the Nightforce ATACR 1-8x, to operators equipped with the MRGG-A and legacy M4A1s. These optics allow for true 1x aiming for room clearing and immediate transition to 8x magnification for positive identification and engagement at 600 meters.

8. Suppression and Signature Reduction

The era of the “unsuppressed” rifle is effectively over in USSOCOM. The requirement for signature reduction is now integral to every small arms solicitation.

8.1 SureFire Dominance

SureFire remains the titan of the suppressor industry. Stemming from the massive $23.3 million Family of Muzzle Brake Suppressors (FMBS) contract (originally 2011, renewed/sustained through 2024), SureFire suppressors (SOCOM556-RC2 and SOCOM762-RC2) are the standard issue for legacy and new platforms.20 Their “Fast-Attach” mounting system is the NATO standard for durability and return-to-zero.

8.2 Sig Sauer SURG

For specialized applications, the Suppressed Upper Receiver Group (SURG) addresses the thermal and gas blowback issues inherent in retrofitting suppressors to M4s. Sig Sauer’s SURG contract, originally awarded in 2018 for $48 million, was extended in July 2023 for an additional five years.22 This system encapsulates the gas block and suppressor within a heat-shielded handguard, protecting the operator from burns and toxic fumes during sustained rates of fire.

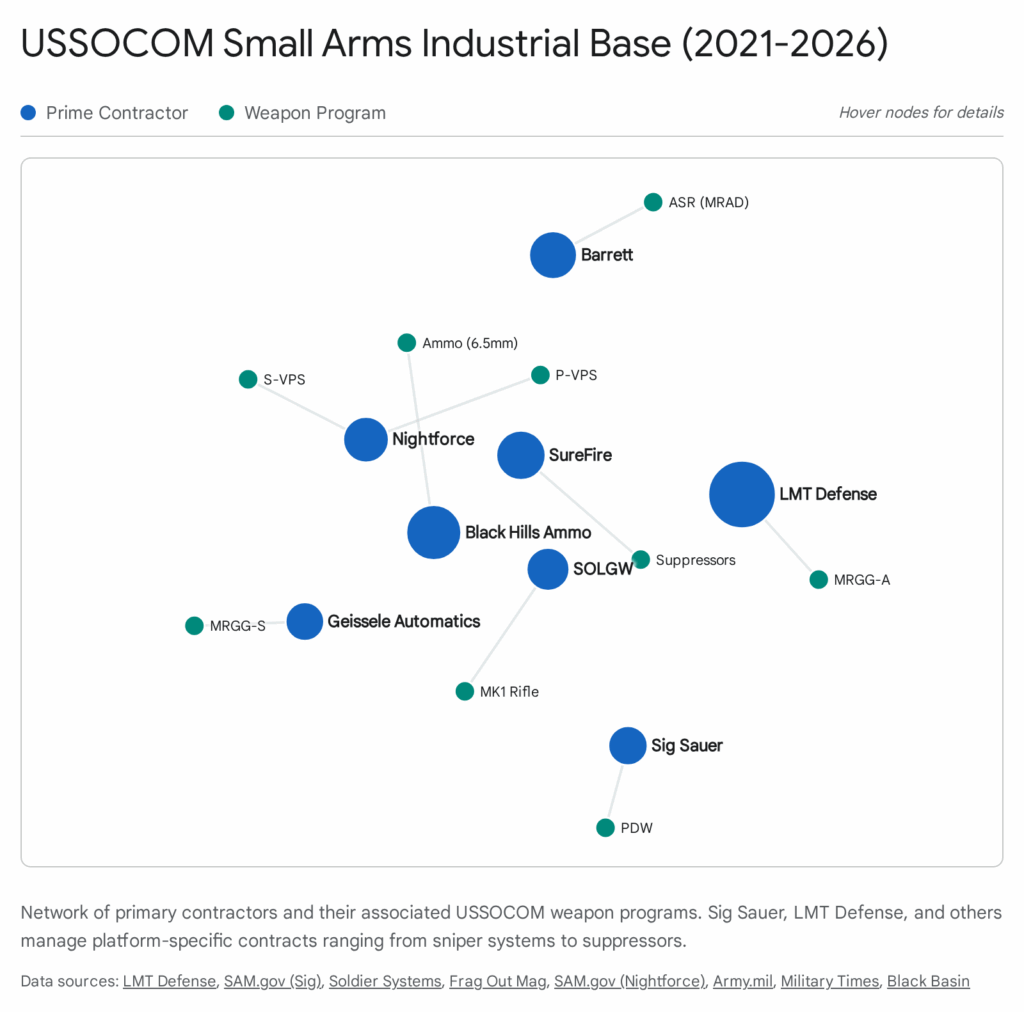

9. Industrial Base Analysis

The contracting data from 2021–2026 reveals a distinct hierarchy and specialization within the small arms industrial base serving USSOCOM.

9.1 The “Super Prime”: Sig Sauer

Sig Sauer has effectively become the small arms prime integrator for the DoD. By securing the PDW, LMG-M, SURG, and the Army’s NGSW contracts, they have achieved a scale of production and R&D that few competitors can match. Their vertical integration—producing the gun, the suppressor, the optic (Electro-Optics division), and the ammunition—allows them to offer “turn-key” systems that reduce integration risk for the government.

9.2 The “Specialized Tier 1”: LMT, Geissele, Barrett, SOLGW

USSOCOM has resisted total consolidation by actively awarding its rifle contracts to specialized manufacturers. LMT Defense, Geissele Automatics, and SOLGW represent the pinnacle of the “AR-15 refinement” industry. These companies built their reputations in the high-end commercial and law enforcement markets. Their selection indicates that USSOCOM values the specific engineering nuances (monolithic rails, optimized gas systems, quality assurance) that these smaller, focused engineering firms provide over the mass-production capacity of legacy giants.

10. Conclusion

The period from 2021 to 2026 will be recorded as the era when USSOCOM severed its ballistic tether to the 20th century. By transitioning its primary infantry systems to 6.5 Creedmoor and.338 Norma Magnum, the Command has effectively doubled the lethality range of the individual operator.

This transition was achieved through a sophisticated acquisition strategy that leveraged the full spectrum of the industrial base. The awards to LMT Defense ($92M MRGG-A) and Geissele Automatics ($29M MRGG-S) provide a versatile, precision-capable rifle fleet. The Sig Sauer PDW ($17M) and SOLGW CAR contracts address the specialized needs of covert and direct action units. Backed by the logistical assurance of Black Hills Ammunition ($40M) and the targeting superiority of Nightforce Optics ($17.6M), USSOCOM has successfully fielded a small arms arsenal designed not just to fight the next war, but to dominate it through superior range, precision, and signature management. The cancellation of the LMG-A remains the only significant outlier in an otherwise cohesive modernization strategy, a gap that will likely be addressed as the relationship between USSOCOM requirements and the Army’s NGSW program matures in the coming years.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- LMT Awarded MRGG Contract | LMT Advanced Technologies, accessed January 5, 2026, https://lmt-at.com/lmt-awarded-ussocom-mrgg-a-contract/

- Medium Range Gas Gun – Assault – SAM.gov, accessed January 5, 2026, https://sam.gov/opp/b1313f5ce16d4523a98e8d189efec40b/view

- The U.S. Special Operations Command has a new assault rifle, the LMT Defense MRGG-A in 6.5 Creedmoor % – Zona Militar, accessed January 5, 2026, https://www.zona-militar.com/en/2025/09/15/the-u-s-special-operations-command-has-a-new-assault-rifle-the-lmt-defense-mrgg-a-in-6-5-creedmoor/

- LMT Wins $93 Million SOCOM 6.5 Creedmoor Rifle Contract – Guns.com, accessed January 5, 2026, https://www.guns.com/news/2025/08/25/lmt-wins-93-million-socom-65-creedmoor-rifle-contract

- USSOCOM Awards Geissele Automatics Contract for MRGG-S (Mid Range Gas Gun – Sniper) – Frag Out! Magazine, accessed January 5, 2026, https://fragoutmag.com/ussocom-awards-geissele-automatics-contract-for-mrgg-s-mid-range-gas-gun-sniper/

- USSOCOM Selects SIG Rattler for Reduced Signature Assault Rifle | Soldier Systems Daily, accessed January 5, 2026, https://soldiersystems.net/2022/09/20/ussocom-selects-sig-rattler-for-reduced-signature-assault-rifle/

- USSOCOM Personal Defense Weapon (PDW) – SAM.gov, accessed January 5, 2026, https://sam.gov/opp/acb5129ead964d5a9d4e34f5993b929b/view

- USSOCOM PDW RSAR Ceiling Increase and Incorporation of 7.62x39mm Kits – HigherGov, accessed January 5, 2026, https://www.highergov.com/contract-opportunity/ussocom-pdw-rsar-cei-pdw762an-award-h240322d0005-sig-sauer-inc-79dcf/

- Sons of Liberty Gun Works Awarded USSOCOM Contract for MK1 …, accessed January 5, 2026, https://soldiersystems.net/2025/11/20/sons-of-liberty-gun-works-awarded-ussocom-contract-for-mk1-rifle/

- Sons of Liberty Gun Works Awarded U.S. SOCOM Contract for MK1 Rifle, accessed January 5, 2026, https://sonsoflibertygw.com/sons-of-liberty-gun-works-awarded-u-s-socom-contract-for-mk1-rifle/

- Special Operators Are Eying This Machine Gun To Solve A Number Of Problems, accessed January 5, 2026, https://www.twz.com/31855/special-operators-are-eying-this-machine-gun-to-solve-a-number-of-problems

- SIG Sauer MMG 338 – Wikipedia, accessed January 5, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SIG_Sauer_MMG_338

- Lightweight Machine Gun-Assault (LMG-A) Call for White Papers 2 – HigherGov, accessed January 5, 2026, https://www.highergov.com/contract-opportunity/lightweight-machine-gun-assault-lmg-a-call-for-w-h9240325f00xx7dec25lmg-acancel-s-486bf/

- US special ops cancels next-gen machine gun development, accessed January 5, 2026, https://defence-blog.com/us-special-ops-cancels-next-gen-machine-gun-development/

- Contracts For Sept. 23, 2025 – Department of War, accessed January 5, 2026, https://www.war.gov/News/Contracts/Contract/Article/4313336/

- U.S. Navy Secures Major 6.5 Creedmoor Ammunition Supply Through $40 Million Contract, accessed January 5, 2026, https://blackbasin.com/news/us-navy-secures-major-65-creedmoor-ammunition-supply-through-40-million-contract/

- US Navy and USMC Order 6.5 Creedmoor Ammunition Worth 40 Million USD – MILMAG, accessed January 5, 2026, https://milmag.pl/en/us-navy-and-usmc-order-6-5-creedmoor-ammunition-worth-40-million-usd/

- Family of Night Force Scopes – SAM.gov, accessed January 5, 2026, https://sam.gov/opp/6499e8f92fb549a0aa9ae32b0799cb03/view

- Nightforce Scopes and Parts IDIQ Contract – HigherGov, accessed January 5, 2026, https://www.highergov.com/idv/H9240322D0009/

- SOCOM awards lots I & II of Family of Muzzle Brake Suppressors to Surefire – Military Times, accessed January 5, 2026, https://www.militarytimes.com/off-duty/gearscout/2011/09/29/socom-awards-lots-i-ii-of-family-of-muzzle-brake-suppressors-to-surefire/

- Surefire Suppressor: U.S. SOCOM Mission-Essential Equipment – Guns and Ammo, accessed January 5, 2026, https://www.gunsandammo.com/editorial/surefire-suppressor-us-socom/457107

- US SOCOM Extends Suppressed Upper Receiver Group (SURG) Contract for 5 More Years, accessed January 5, 2026, https://www.thefirearmblog.com/blog/2023/07/20/us-socom-extends-suppressed-upper-receiver-group-surg-contract-5-years/