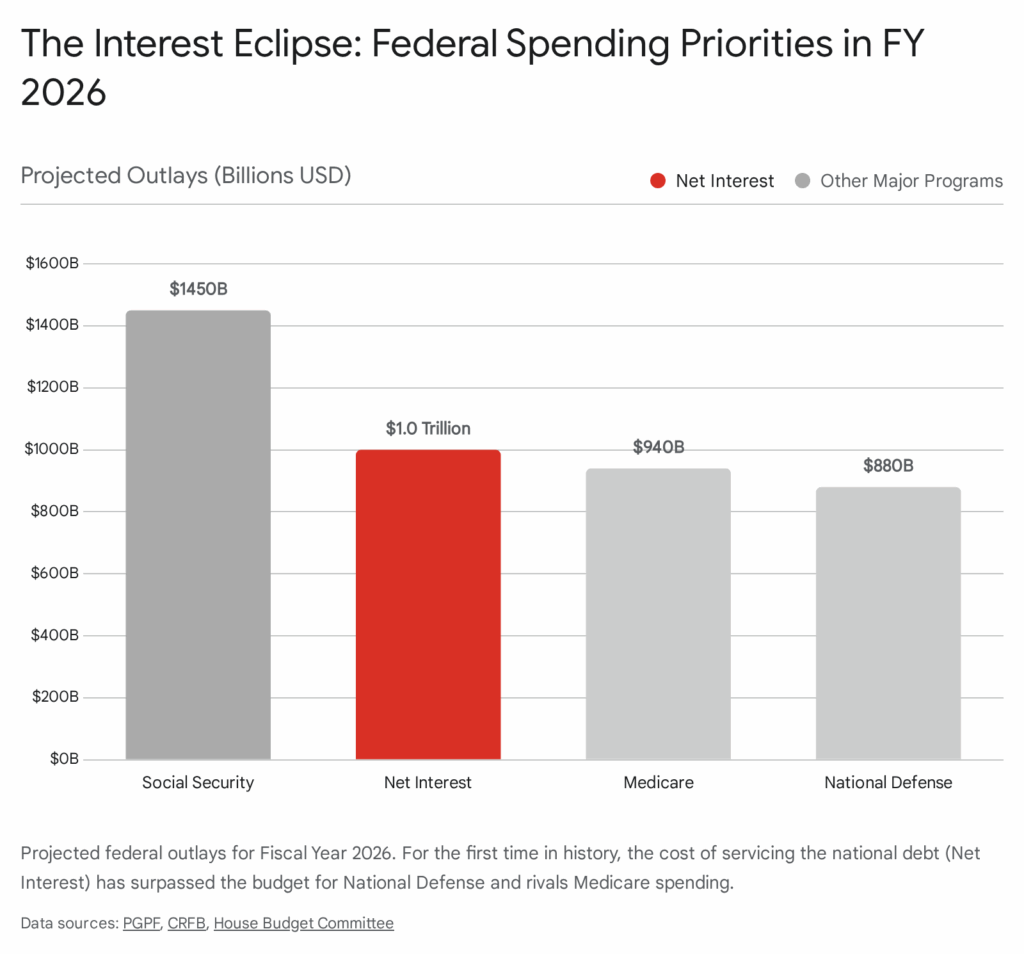

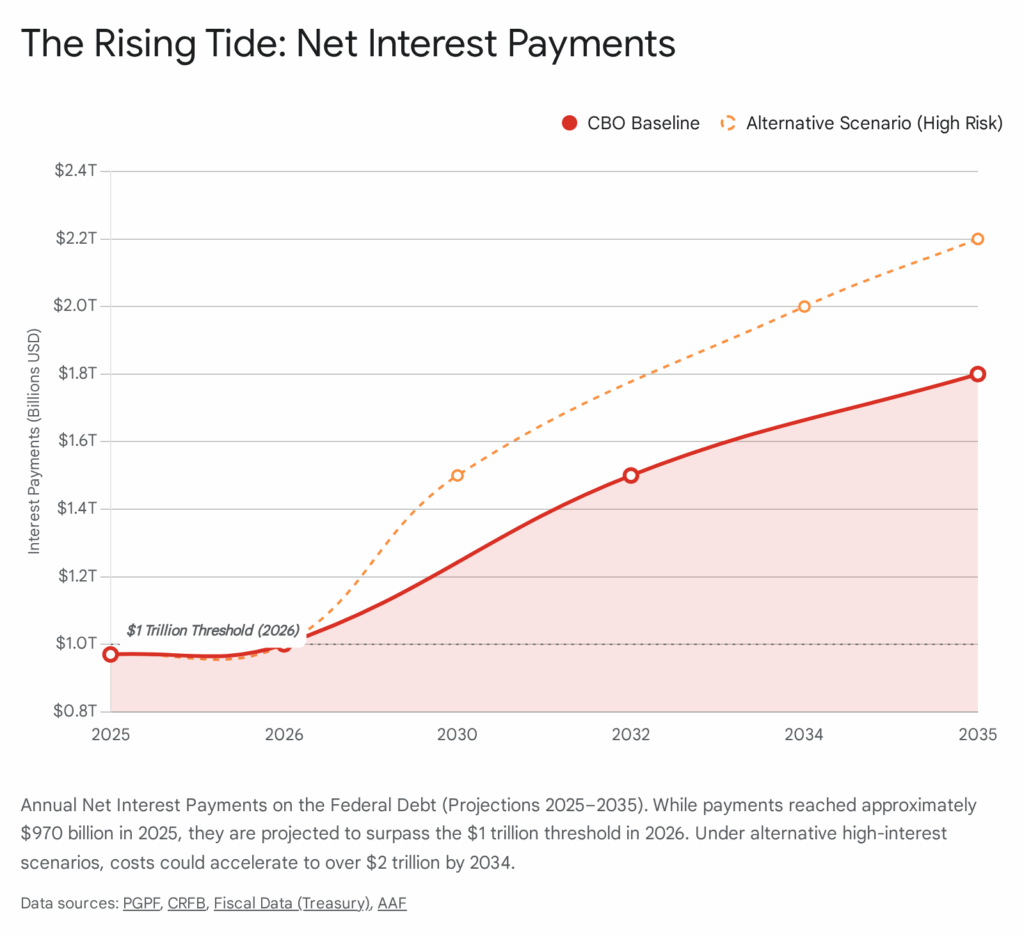

As of January 2026, the United States stands at a precipitous fiscal crossroads, facing a convergence of economic pressures that threaten the fundamental stability of the nation’s currency and its standing in the global order. The national debt has surpassed $38 trillion, a figure that now exceeds the total annual economic output of the nation, with a debt-to-GDP ratio approaching 120%.1 For the first time in American history, the federal government’s annual expenditure on net interest payments has eclipsed the budget for national defense, signaling a structural shift in the nation’s financial priorities from investment and security to debt service.3 This milestone is not merely symbolic; it represents a mathematical inflection point where the cost of past consumption begins to cannibalize the future capacity of the state to function.

The recent enactment of the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (OBBBA) in mid-2025 has further accelerated these trends, introducing permanent tax reductions without commensurate spending offsets, thereby widening the deficit to nearly $1.8 trillion annually.5 While politically expedient, these measures have exacerbated the structural imbalance between revenues and outlays, forcing the Treasury to issue debt at a pace that global markets are increasingly hesitant to absorb.

This report serves as a comprehensive advisory on the mechanics of money supply, the dangers of unconstrained fiscal expansion, and the long-term economic perils of “printing money” (monetization) as a remedy for sovereign debt. Contrary to the seductive simplicity of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) or the political convenience of quantitative easing, the fundamental laws of economics remain immutable: money is a store of value, not a creator of wealth. An artificial expansion of the money supply, decoupled from productivity growth, inevitably results in the devaluation of the currency.

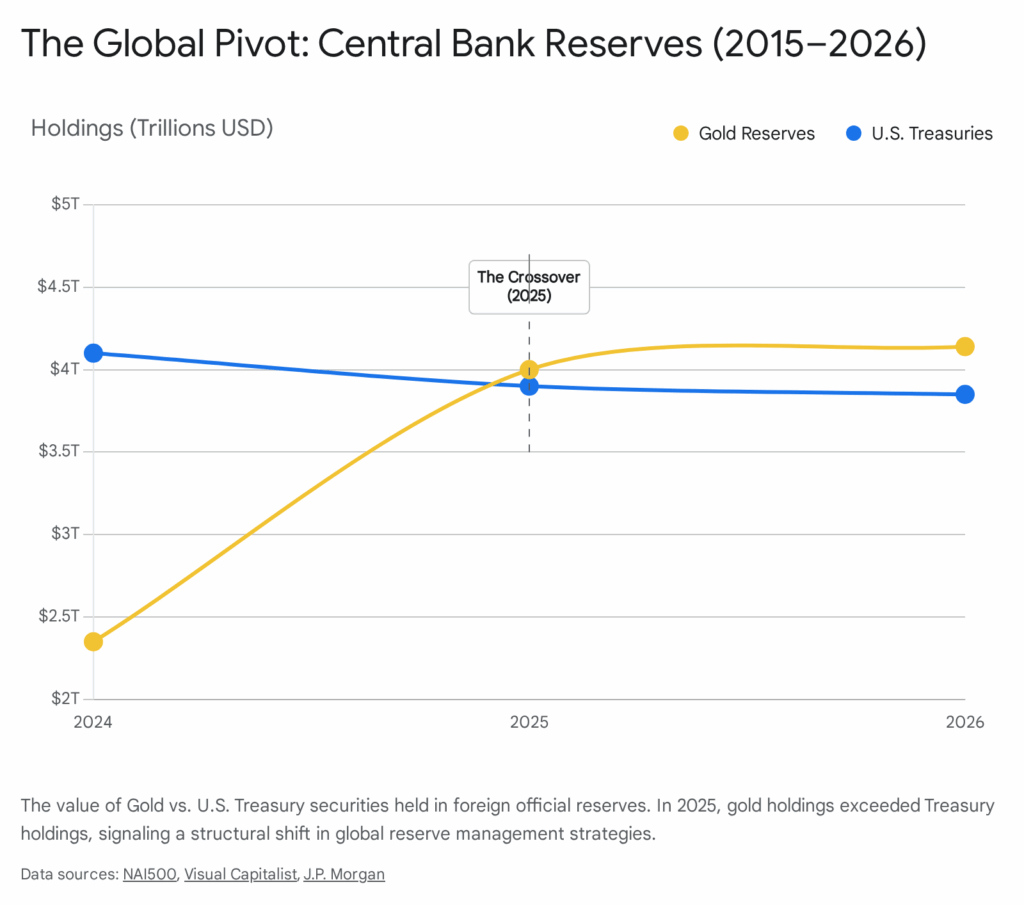

The evidence is mounting. Inflation, having proved stickier than the “transitory” narratives of the early 2020s, remains elevated at 2.7% as of December 2025, buoyed by tariff-induced price pressures and resilient demand.7 Simultaneously, a quiet but profound shift is occurring in the global financial architecture; in 2025, for the first time in decades, the value of gold held by foreign central banks surpassed their holdings of U.S. Treasuries.9 This “de-dollarization” trend represents a vote of no confidence in the long-term purchasing power of the dollar and the fiscal discipline of the United States government.

To preserve the standard of living for the American citizenry and maintain the United States’ geopolitical leverage, the federal government must reject the siren song of monetization. Instead, it must undertake the arduous but necessary work of restoring fiscal balance through spending control and structural reform. This report details the economic principles underlying these conclusions, offering a sober analysis of why the printing press is an instrument of ruin, not salvation.

The Precipice of 2026: A Fiscal State of the Union

The fiscal landscape of early 2026 is defined by a series of unprecedented milestones that suggest the United States economy has entered a new and precarious phase of its history. The era of “easy money”—characterized by near-zero interest rates and low inflation—has decisively ended, replaced by a regime of high debt service costs, persistent inflationary pressure, and growing skepticism from international creditors.

The New Arithmetic of Debt

As of January 7, 2026, the total gross national debt of the United States stands at approximately $38.43 trillion.10 To contextualize this figure, it represents an increase of $2.25 trillion in a single year, averaging a daily accumulation of over $8 billion.10 This acceleration is not the result of a singular crisis, such as a war or a pandemic, but rather the outcome of structural profligacy. The debt per household has reached $285,127, a burden that is effectively a silent mortgage on the future earnings of every American family.10

The composition of this debt has also shifted. In previous decades, deficits were often financed by domestic savings or the reliable recycling of trade surpluses from nations like China and Japan. However, in 2026, the demand dynamics have inverted. Foreign central banks, once the most voracious consumers of U.S. debt, have become net sellers, forcing the domestic market and the Federal Reserve to absorb a larger share of issuance.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) and Structural Deficits

The legislative centerpiece of 2025, the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (OBBBA), has fundamentally altered the trajectory of federal revenues. Signed into law on July 4, 2025, the OBBBA introduced a suite of populist tax cuts designed to alleviate the cost-of-living crisis for specific demographics.5 Key provisions include:

- Senior Deduction: An additional $6,000 standard deduction for individuals over age 65, aimed at protecting retirees from inflation.5

- Overtime Tax Exemption: A deduction for overtime pay, theoretically designed to incentivize labor participation but practically reducing the income tax base.11

- Car Loan Interest Deduction: Allowing the deduction of interest on vehicle loans, a policy that encourages debt-fueled consumption in the auto sector.5

While these measures provided immediate political relief, their fiscal impact has been corrosive. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the cumulative effect of the OBBBA will be a 29 percentage point increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio over the next three decades.1 By permanently reducing the tax base without addressing the primary drivers of mandatory spending—Social Security and Medicare—the government has locked in a structural deficit that persists even during periods of economic expansion.

The deficit for Fiscal Year 2025 reached $1.8 trillion, and projections for FY 2026 suggest no abatement.6 This creates a “fiscal dominance” scenario where the government’s need for financing overrides all other economic considerations, including the central bank’s mandate to control inflation.

The Nature of Money: A Primer on Value and Trust

To understand why the government cannot simply print $38 trillion to retire its debt, one must first strip away the complexities of modern finance and examine the fundamental nature of money itself. In the public imagination, money is often conflated with wealth. If an individual has more dollars, they are wealthier; therefore, it seems intuitive that if the nation had more dollars, the nation would be wealthier. This is a dangerous fallacy known as the “money illusion”.13

Money as a Measuring Stick

Money is not wealth. Wealth consists of real assets: fertile land, factories, technological infrastructure, skilled labor, energy resources, and finished goods. Money is merely the measuring stick used to value these assets and the medium of exchange used to trade them. It is a claim check on society’s production.

If the government prints more claim checks without increasing the production of goods and services, the value of each individual claim check must mathematically decline. This is not a policy choice; it is an arithmetic certainty derived from the laws of supply and demand.

The Equation of Exchange

Economists utilize the Equation of Exchange to describe the mechanical relationship between the money supply and the price level. This equation serves as the cornerstone for understanding inflation.

M x V = P x Q

Where:

- M (Money Supply): The total amount of currency in circulation.

- V (Velocity of Money): The frequency with which the average unit of currency is spent on new goods and services over a given period.

- P (Price Level): The average price of goods and services in the economy.

- Q (Real Output): The total quantity of goods and services produced (Real GDP).

In this equation, both sides must always be equal. The total amount of money spent (M x V) must equal the total value of goods sold (P x Q).

If the government increases the money supply (M) significantly to pay its debts, one of two things must happen to balance the equation:

- Real Output (Q) increases: The economy produces more goods to soak up the extra cash.

- Price Level (P) increases: Prices rise to reflect the abundance of cash relative to goods.

In a mature, industrialized economy like the United States in 2026, Real Output (Q) grows relatively slowly—typically 2-3% per year. Therefore, if the money supply (M) is expanded by 20% or 30% to finance a deficit, output cannot possibly keep pace. The result is that the Price Level (P) must rise. This is the definition of inflation: too much money chasing too few goods.14

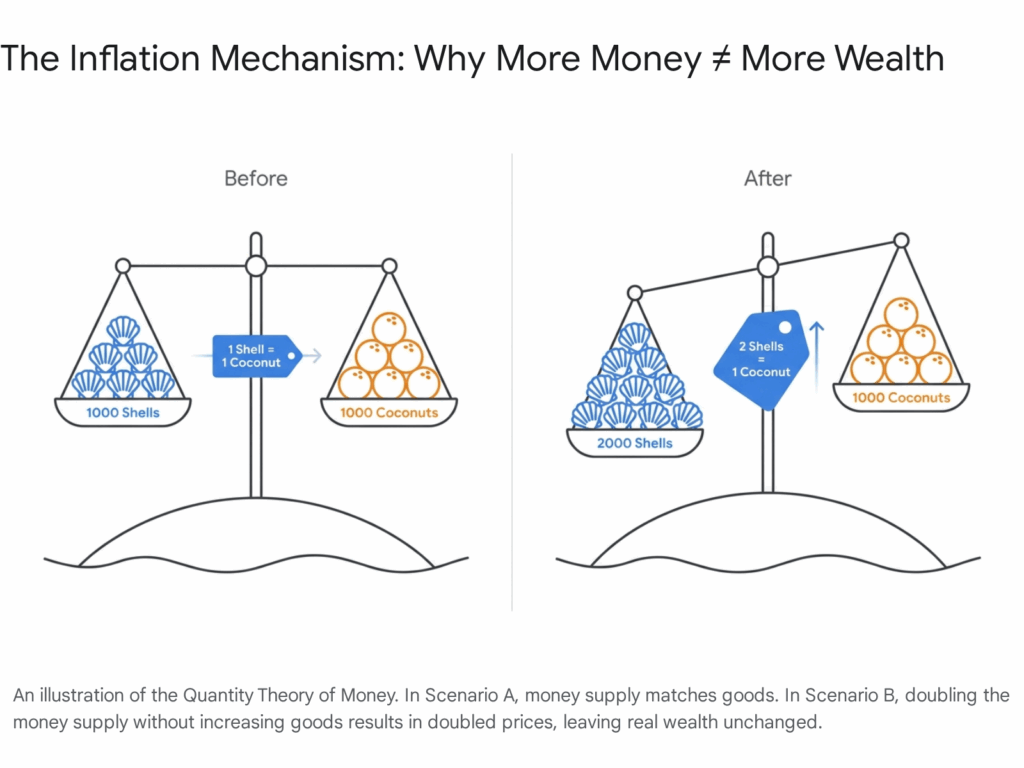

The “Island Economy” Analogy

To visualize this, consider an isolated island economy that produces exactly 1,000 coconuts per year. The islanders use seashells as currency, and there are 1,000 shells in circulation. In this equilibrium, the price of one coconut is one shell.

Now, suppose the island chief discovers a hidden cave containing 1,000 new shells and distributes them equally among the villagers. The villagers feel momentarily rich—their nominal wealth has doubled. They rush to the market to buy more coconuts. However, the island still only produces 1,000 coconuts. There are now 2,000 shells chasing 1,000 coconuts. The price of a coconut will inevitably rise to two shells.

The villagers have twice as much money, but they can buy exactly the same amount of food. No new wealth was created; the currency was simply devalued. The government’s attempt to solve a resource constraint by printing money is equivalent to the chief trying to feed the village by printing more meal tickets. It does not create more food; it only makes the tickets worth less.

The Mechanism of Monetization and the Federal Reserve

The process by which the U.S. government “prints money” is often misunderstood. It is not as simple as the Treasury Department turning on a printing press. The process involves a complex interaction between the Treasury and the Federal Reserve, a process known technically as “debt monetization.”

Financing vs. Monetizing: A Critical Distinction

Under normal circumstances, when the U.S. government spends more than it taxes, it finances the deficit by borrowing. The Treasury issues bonds (Treasuries) and sells them to private investors, pension funds, and foreign governments. In this scenario, existing money is transferred from the private sector to the government. The total supply of money in the economy remains relatively stable; it merely changes hands. This is sustainable as long as there are willing buyers for U.S. debt at reasonable interest rates.

Monetization occurs when there are insufficient private buyers for the government’s debt, or when interest rates rise so high that the government cannot afford to pay them. In this scenario, the Federal Reserve steps in as the “buyer of last resort.” The Fed purchases the Treasury bonds using money that it creates instantly (digital reserves).15

- The Treasury issues debt.

- The Federal Reserve buys the debt.

- The Fed pays with newly created digital dollars.

- These new dollars enter the banking system and eventually flow into the broader economy.

This process is functionally equivalent to printing money. It expands the monetary base (M) without a corresponding increase in production (Q).

The Danger of Quantitative Easing (QE) Becoming Permanent

Following the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic, the Federal Reserve engaged in Quantitative Easing (QE), purchasing trillions of dollars in bonds to stabilize markets. Proponents argued this would not cause inflation because the velocity of money (V) was collapsing during those crises.16 The new money largely sat in bank reserves rather than circulating in the economy.

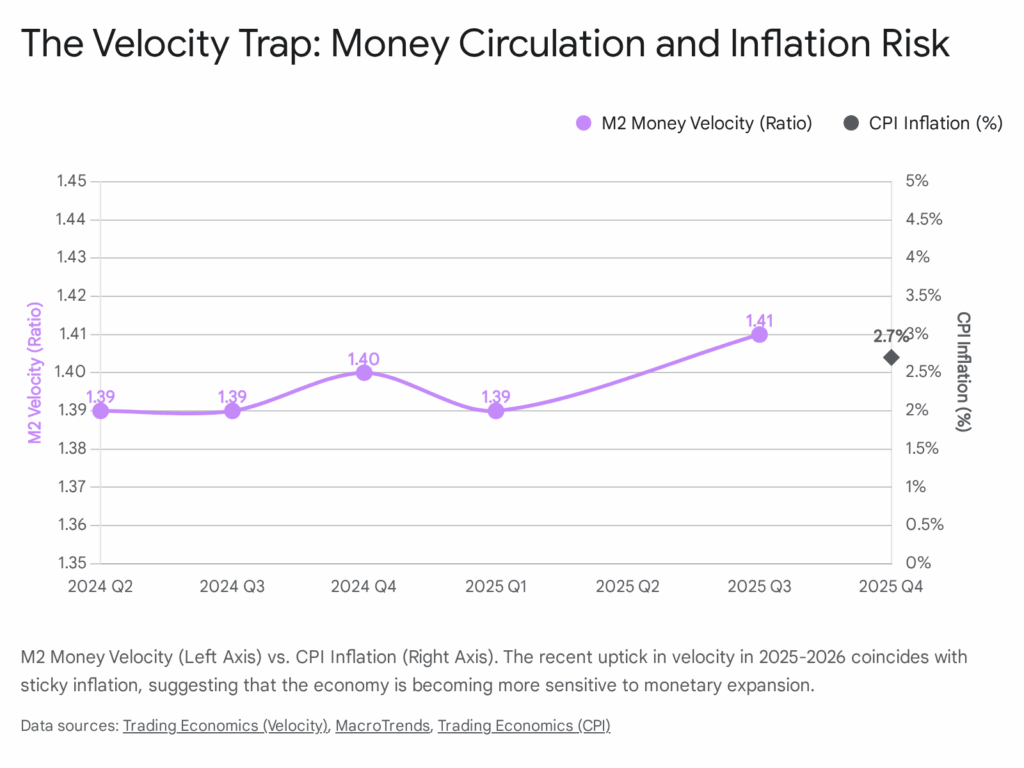

However, the situation in 2026 is fundamentally different. The economy is not in a deflationary collapse; it is facing supply constraints and sticky inflation. The velocity of money has stabilized and is beginning to tick upward.17 If the Federal Reserve were to resume large-scale asset purchases (monetization) to fund the $1.8 trillion deficit, that money would not sit idle. It would flow into an economy already near capacity, acting as high-octane fuel for inflation.

Recent data confirms this risk. M2 money velocity, which hit historic lows in 2020, has recovered to 1.406 as of late 2025.17 This uptick indicates that each dollar creates more inflationary pressure today than it did five years ago. This “Velocity Trap” means the Federal Reserve has far less room to maneuver than it did during previous crises.

The Interest Burden: A Structural Crisis

The most immediate and tangible consequence of the national debt is the cost of servicing it. For decades, the United States benefited from a low-interest-rate environment that made borrowing virtually free. That era has abruptly ended, exposing the federal budget to the harsh reality of compound interest.

The $1 Trillion Milestone

In Fiscal Year 2025, the federal government spent $970 billion on net interest payments.3 Projections for FY 2026 indicate that this figure will surpass $1 trillion for the first time in history.4

To grasp the magnitude of this expenditure, one must compare it to other national priorities. In 2026, the United States government will spend more on interest payments to bondholders than it spends on the entire Department of Defense. It will spend more on interest than on Medicaid. Interest payments have become the second-largest line item in the federal budget, trailing only Social Security.4

This represents a profound misallocation of national resources. Every dollar spent on interest is a dollar that cannot be spent on infrastructure, education, research, or tax relief. It is a retrospective payment for past consumption that yields no current economic benefit. This phenomenon is known as “crowding out,” where debt service squeezes all other discretionary spending out of the budget.

The Debt Spiral Mechanism

The rising interest burden creates a dangerous feedback loop known as a “debt spiral.” Because the government runs a primary deficit (spending more than revenue even before interest is paid), it must borrow money just to pay the interest on existing debt.

- The government borrows to pay interest.

- The total debt stock increases.

- Interest payments rise further due to the larger debt stock.

- The government must borrow even more the following year.

As of December 2025, the average interest rate on total marketable U.S. debt had risen to 3.362%, up from 1.552% just five years prior.20 If interest rates were to rise by just one additional percentage point, it would add hundreds of billions of dollars to the annual deficit, accelerating the spiral. This sensitivity to interest rates holds the federal budget hostage to bond market volatility.

The visualization above highlights the stark reality of the 2026 budget. With interest payments consuming such a vast proportion of federal outlays, the government loses fiscal flexibility. In the event of a new recession, war, or pandemic, the fiscal capacity to respond is severely constrained by the existing obligations to bondholders.

The Global Dimension: De-Dollarization and the Erosion of Trust

The United States has long enjoyed a unique economic advantage known as the “exorbitant privilege.” Because the U.S. dollar serves as the world’s primary reserve currency, the U.S. can borrow money more cheaply and easily than any other nation. Global demand for dollars forces other countries to hold U.S. Treasury bonds as a safe asset. This allows the U.S. to run persistent trade deficits—importing goods and exporting dollars—without suffering an immediate currency collapse.

However, this privilege is contingent upon trust. Global investors must trust that the U.S. government will maintain the value of the dollar and honor its debts without resorting to inflation. In 2026, that trust is fracturing.

The Gold-Treasury Crossover of 2025

A watershed moment in international finance occurred in 2025: for the first time in nearly three decades, the value of gold held by foreign central banks surpassed their holdings of U.S. Treasuries.9

This is a geopolitical signal of the highest order. Central banks—the most conservative investors in the world—are actively diversifying away from the dollar. Nations such as China, India, and even historical allies are increasing their gold reserves while reducing or stagnating their exposure to U.S. debt.21 They are choosing a tangible, neutral asset (gold) over the financial promises of the United States government.

The drivers of this shift are twofold:

- Sanction Risk: The weaponization of the dollar financial system has demonstrated to foreign nations that dollar reserves can be frozen or seized. Gold, stored domestically, carries no such counterparty risk.

- Fiscal Skepticism: Foreign creditors are observing the U.S. fiscal trajectory—$38 trillion in debt and rising—and concluding that the only way the U.S. can pay its obligations is by devaluing the currency. They are exiting the market before that devaluation accelerates.

The Impact of De-Dollarization on the American Household

If the trend of de-dollarization continues, the consequences for the average American will be severe. A reduction in global demand for dollars leads to a depreciation of the currency’s exchange rate.

- Imported Inflation: As the dollar weakens, the cost of imported goods rises. Everything from electronics and clothing to automobile parts and machinery becomes more expensive. This acts as a tax on American consumers, lowering their standard of living.23

- Higher Interest Rates: If foreign central banks stop buying U.S. Treasuries, the U.S. government must offer higher interest rates to attract other buyers. This pushes up borrowing costs across the entire economy, making mortgages, car loans, and business credit more expensive.24

- Loss of Purchasing Power: The “strong dollar” has allowed Americans to consume more than they produce for decades. A reversion to the mean would require a painful contraction in consumption.

The Specter of Inflation: Why “Sticky” is Dangerous

Inflation is often described as a tax that no one voted for. It transfers wealth from savers (who hold currency) to debtors (who pay back loans with devalued money). In 2026, the U.S. is grappling with “sticky” inflation—a rate that refuses to return to the 2% target despite the Federal Reserve’s efforts.

As of December 2025, the CPI stood at 2.7%, with core measures showing similar resistance.8 This is not the runaway inflation of the 1970s, but it is high enough to erode wages and destabilize planning.

The Tariff Factor

The current inflationary environment is complicated by trade policy. The tariffs maintained and expanded by the administration have raised the cost of imported goods.25 In a normal environment, these costs might be absorbed by corporate margins. However, in an environment of high demand and labor shortages, corporations are passing these costs directly to consumers.

The Risk of a Wage-Price Spiral

The most dangerous phase of inflation is when it becomes embedded in psychology. If workers expect prices to rise by 3% or 4% every year, they will demand commensurate wage increases. Corporations, facing higher labor costs, will raise prices further to protect margins. This feedback loop, known as a wage-price spiral, is incredibly difficult to break without causing a recession.

If the government were to resort to monetization (printing money) to solve its debt problem in this environment, it would pour gasoline on the fire. The public, sensing that the currency is being debased, would accelerate their spending to exchange rapidly depreciating dollars for tangible goods. This increase in the velocity of money would cause inflation to spike far beyond the proportional increase in the money supply.

Historical Case Studies: The Road to Ruin

The laws of economics are not suspended for great powers. History provides stark warnings of what happens when nations attempt to print their way out of debt.

Weimar Germany (1923)

Faced with crushing war reparations and a striking workforce in the Ruhr, the German government printed money to pay its bills. The result was one of the most famous hyperinflations in history. Prices doubled every few days. The middle class was wiped out as savings evaporated. The social chaos that ensued paved the way for political extremism and the ultimate destruction of the republic.26

Zimbabwe (2007-2008)

To fund patronage networks and cover the collapse of the agricultural sector, the Zimbabwean government printed money on an industrial scale. Inflation reached 79 billion percent per month. The currency became worthless litter in the streets, and the economy reverted to a primitive barter system. The lesson is that once confidence in a currency is lost, it is almost impossible to regain.26

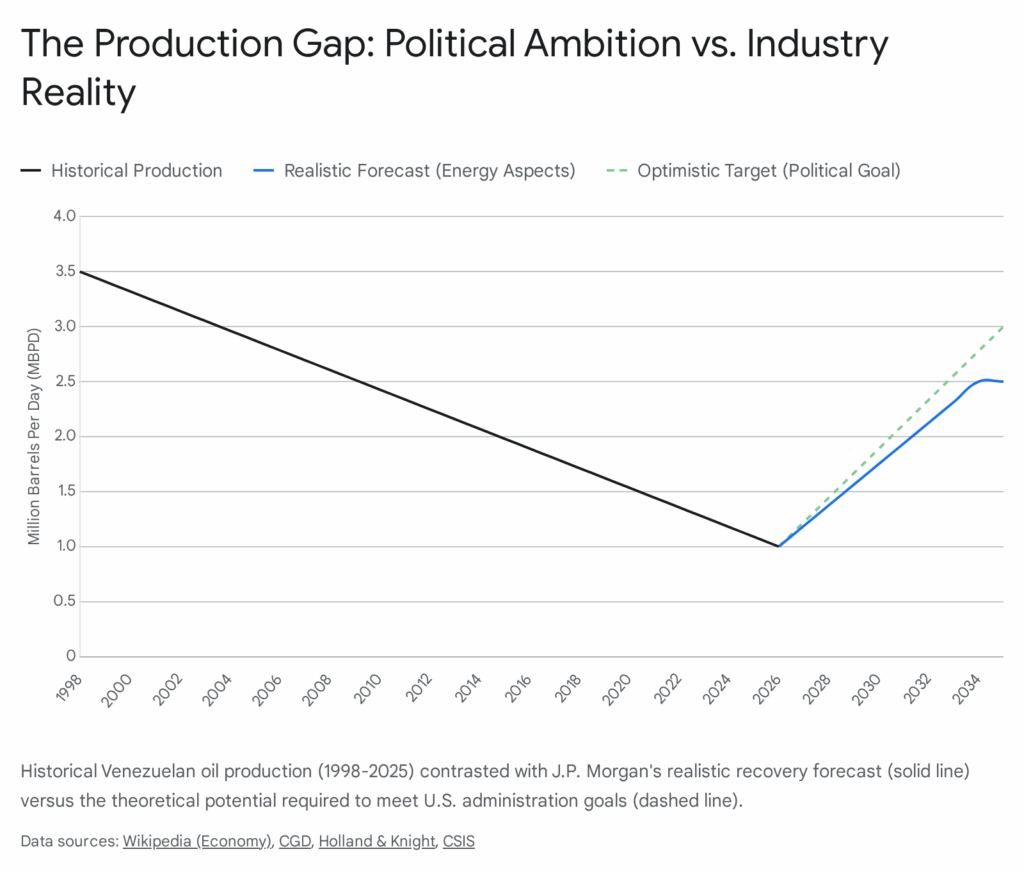

Venezuela (2016-Present)

Despite sitting on the world’s largest oil reserves, Venezuela descended into economic ruin through a combination of mismanagement and monetization. The government printed money to fund social programs as oil revenues collapsed. The resulting hyperinflation destroyed the price system, leading to shortages of food and medicine and a massive refugee crisis.27

While the United States is a far more robust and diversified economy than these examples, the underlying principle remains: no nation can consume more than it produces forever by simply printing more claim checks.

The Path Forward: Solvency over Expediency

The United States faces a choice between two painful paths. The first is the path of least resistance: continuing to run massive deficits, monetizing the debt, and accepting a future of high inflation, currency devaluation, and diminished global standing. The second is the path of fiscal control.

Why We Must Balance the Budget

Balancing the budget is not an ideological fetish; it is a mathematical necessity for long-term stability.

- Stop the Debt Spiral: We must reach a “primary balance” where tax revenues cover all non-interest spending. This stops the debt from growing faster than the economy.

- Restore Trust: A credible plan to stabilize the debt would reassure global markets, lowering interest rates and reducing the cost of servicing the debt.

- Control Inflation: By reducing government borrowing, we reduce the aggregate demand pressure that drives inflation. This allows the Federal Reserve to normalize interest rates without crushing the economy.

Necessary Reforms

Achieving this will require difficult decisions that politicians have long avoided:

- Entitlement Reform: The growth of Social Security and Medicare spending must be addressed through means-testing, retirement age adjustments, or efficiency improvements. These programs are the primary drivers of long-term debt.

- Spending Restraint: The era of “emergency” spending for non-emergencies must end. Discretionary spending should be capped or reduced to pre-pandemic levels.

- Revenue Adequacy: The tax code must be optimized to generate sufficient revenue to fund the government’s core functions. This may require revisiting the unfunded tax cuts of the OBBBA.

Conclusion

The printing press is a seductive illusion. It promises the ability to pay debts without sacrifice, to consume without producing, and to govern without choosing. But economics is the study of scarcity, and the printing press cannot create resources. It can only redistribute claims on existing resources, typically from the prudent to the profligate.

For the United States to remain a prosperous, stable, and sovereign nation, it must regain control of its checkbook. The sovereign solvency crisis of 2026 is a warning light that can no longer be ignored. We must choose the hard path of discipline today to ensure the survival of the American promise for tomorrow.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- Projecting Federal Deficits and Debt, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.nber.org/digest/202601/projecting-federal-deficits-and-debt

- Climbing US government debt casts a fiscal shadow – Deloitte, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/topics/economy/spotlight/us-national-debt-fiscal-effects.html

- Interest Costs on the National Debt – Peterson Foundation, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.pgpf.org/programs-and-projects/fiscal-policy/monthly-interest-tracker-national-debt/

- Trillion-Dollar Interest Payments Are the New Norm-2025-12-16, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.crfb.org/blogs/trillion-dollar-interest-payments-are-new-norm

- One, Big, Beautiful Bill provisions | Internal Revenue Service, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/one-big-beautiful-bill-provisions

- CBO Estimates $1.8 Trillion Deficit for Fiscal Year 2025, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.crfb.org/press-releases/cbo-estimates-18-trillion-deficit-fiscal-year-2025

- Inflation Nowcasting – Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.clevelandfed.org/indicators-and-data/inflation-nowcasting

- United States Inflation Rate – Trading Economics, accessed January 13, 2026, https://tradingeconomics.com/united-states/inflation-cpi

- Gold Surpasses US Treasuries to Become World’s Largest Reserve Asset, accessed January 13, 2026, https://nai500.com/blog/2026/01/gold-surpasses-us-treasuries-to-become-worlds-largest-reserve-asset/

- National Debt Hits $38.43 Trillion, Increased $2.25 Trillion Year over Year, $8.03 Billion Per Day, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/2026/1/national-debt-hits-38-43-trillion-increased-2-25-trillion-year-over-year-8-03-billion-per-day

- One, Big, Beautiful Bill Act: Tax deductions for working Americans and seniors – IRS, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/one-big-beautiful-bill-act-tax-deductions-for-working-americans-and-seniors

- Monthly Budget Review: Summary for Fiscal Year 2025, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/61307

- The Problem with Printing Money – Economics Help, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/634/economics/the-problem-with-printing-money/

- Why Does Printing More Money Make Everything More Expensive? – Reddit, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.reddit.com/r/AskEconomics/comments/1ba3wki/why_does_printing_more_money_make_everything_more/

- Is QE monetizing the debt, and what does that even mean? | by Mark Woodworth – Medium, accessed January 13, 2026, https://medium.com/@markcwoodworth/is-qe-monetizing-the-debt-and-what-does-that-even-mean-2a6e9dd3b682

- Money and Inflation Explained: Feducation Video Series | St. Louis Fed, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.stlouisfed.org/education/feducation-video-series/money-and-inflation-explained

- United States – Velocity of M2 Money Stock – 2026 Data 2027 Forecast 1959-2025 Historical, accessed January 13, 2026, https://tradingeconomics.com/united-states/velocity-of-m2-ratio-q-sa-fed-data.html

- Interest on the Debt to Grow Past $1 Trillion Next Year, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.crfb.org/blogs/interest-debt-grow-past-1-trillion-next-year

- Deficit Tracker – Bipartisan Policy Center, accessed January 13, 2026, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/report/deficit-tracker/

- Debt Dashboard – U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/debt-dashboard

- Criminal probe at Federal Reserve to spur gold ETF demand, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.etftrends.com/criminal-probe-federal-reserve-spur-gold-etf-demand/

- Gold overtakes U.S. Treasuries as the world’s largest foreign reserve asset in 2026 — can gold challenge the U.S. dollar’s dominance and hold its ground? – The Economic Times, accessed January 13, 2026, https://m.economictimes.com/news/international/us/gold-overtakes-u-s-treasuries-as-the-worlds-largest-foreign-reserve-asset-in-2026-can-gold-challenge-the-u-s-dollars-dominance-and-hold-its-ground/articleshow/126420128.cms

- De-dollarization: The end of dollar dominance? – J.P. Morgan, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.jpmorgan.com/insights/global-research/currencies/de-dollarization

- How Could Federal Debt Affect You? – GAO.gov, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.gao.gov/americas-fiscal-future/how-could-federal-debt-affect-you

- Trump Tariffs: Tracking the Economic Impact of the Trump Trade War – Tax Foundation, accessed January 13, 2026, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/trump-tariffs-trade-war/

- The Worst Cases Of Hyperinflation Of All Time – Retirable, accessed January 13, 2026, https://retirable.com/advice/lifestyle/worst-hyperinflation-all-time

- Venezuela’s Hyperinflation—Weimar or Zimbabwe on the Caribbean?, accessed January 13, 2026, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/venezuelas-hyperinflation-weimar-or-zimbabwe-caribbean-27487