| This is a time-sensitive special report and is based on information available as of January 5, 2026. Due to the situation being very dynamic the following report should be used to obtain a perspective but not viewed as an absolute. |

The geopolitical landscape of the Caribbean Basin underwent a cataclysmic shift on January 3, 2026, with the United States military intervention in Venezuela, specifically the capture of Nicolás Maduro and the subsequent assumption of operational control over the nation’s petroleum infrastructure. For the Republic of Cuba, this event represents a strategic shock of existential magnitude, comparable only to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. However, unlike the gradual decline of the “Special Period” in the 1990s, the current crisis unfolds with immediate, kinetic velocity due to the imposition of a strict US naval quarantine under Operation Southern Spear.

This report, prepared for national security and foreign affairs stakeholders, provides an exhaustive analysis of the cascading impacts on the Cuban state. The central finding is that the disruption of the Caracas-Havana energy axis is not merely a logistical bottleneck but a systemic termination of the economic model that has sustained the Cuban Communist Party (PCC) for a quarter-century. The symbiosis, wherein Venezuelan hydrocarbons were exchanged for Cuban intelligence and medical services, has been severed at the source.

The analysis projects a rapid, multi-sectoral collapse within Cuba. The electrical grid, already fragile, faces total structural failure as the 35,000–50,000 barrels per day (bpd) of subsidized Venezuelan crude and refined products are halted. This energy deficit will trigger a chain reaction: the paralysis of mechanized agriculture leading to acute food insecurity; the collapse of water sanitation systems dependent on diesel pumps; and the evaporation of hard currency revenues previously derived from re-exporting Venezuelan fuel.

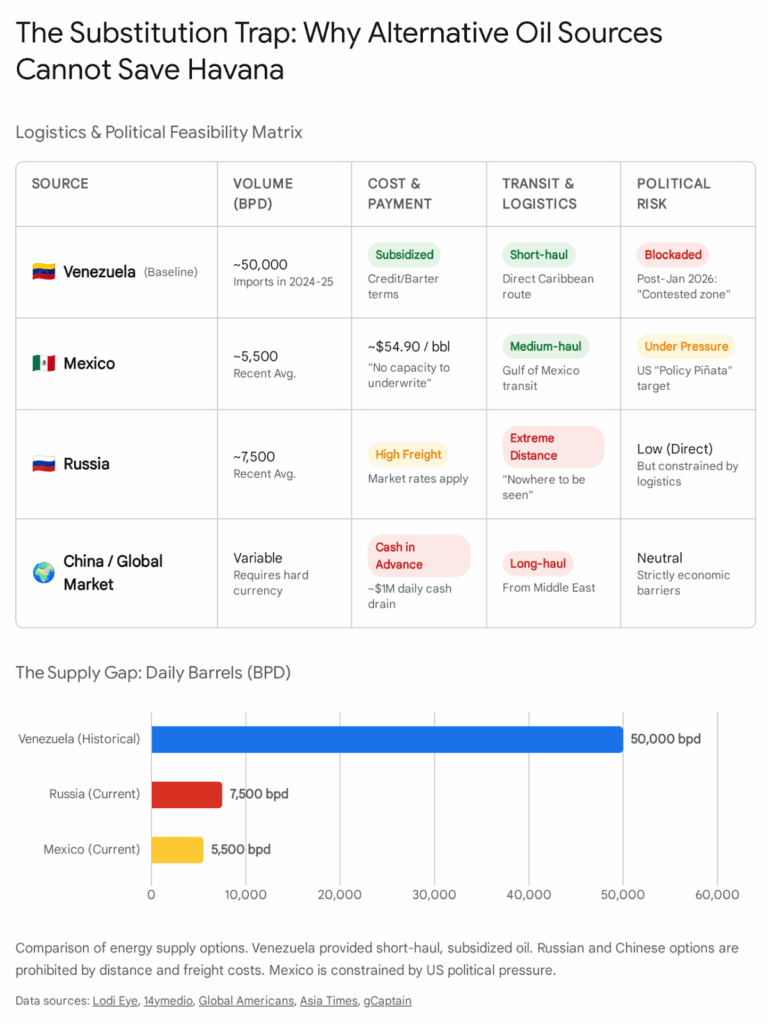

Furthermore, the diplomatic and economic isolation of Havana is compounded by the “US Majors” strategy for Venezuela’s rehabilitation. The roadmap for Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) under US provisional authority prioritizes the commercial reintegration of Venezuelan crude into the US Gulf Coast refining complex, explicitly excluding subsidized political transfers to the Caribbean. Regional actors such as Mexico, constrained by their own economic entanglements with the US, lack the capacity to fill the void. Russia and China, while politically sympathetic, face insurmountable logistical and financial barriers to replacing Venezuela as a distinct energy patron.

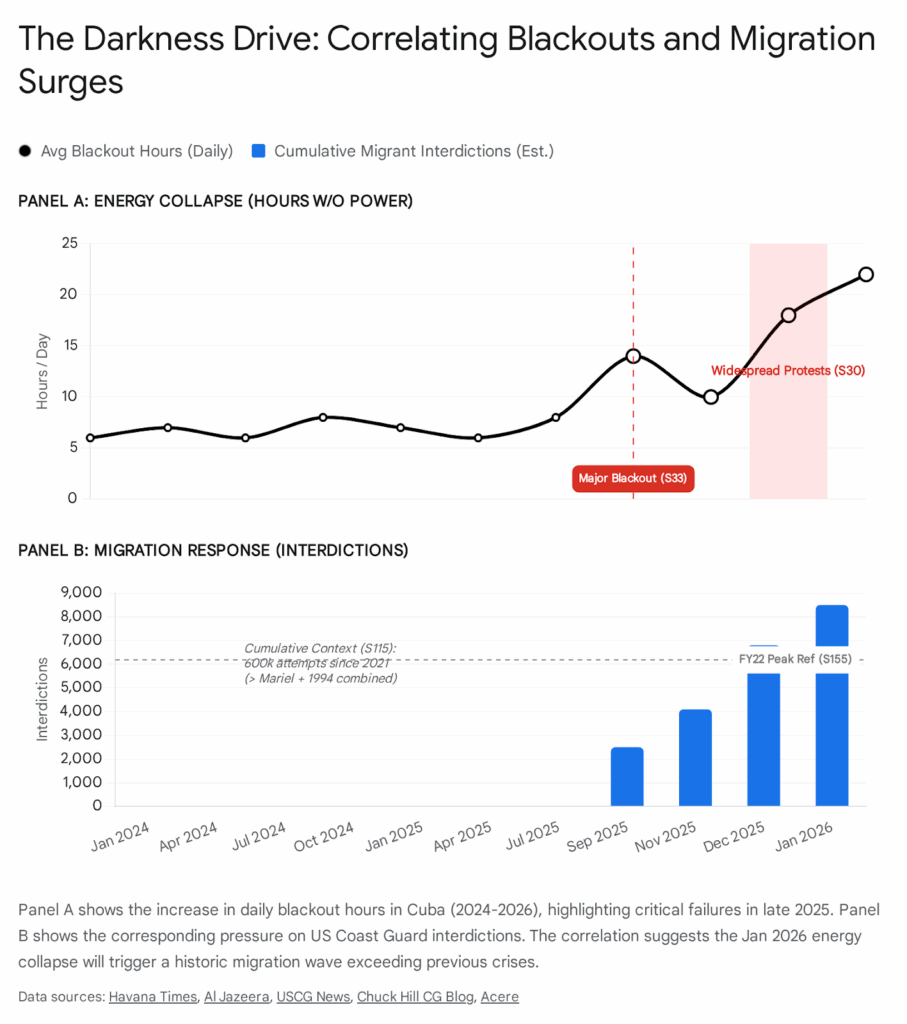

Consequently, the outlook for Q1 and Q2 2026 indicates a high probability of severe internal instability in Cuba, characterized by nationwide blackouts exceeding 20 hours daily, the erosion of the regime’s internal security capacity due to fuel shortages, and a mass migration event potentially exceeding historical precedents. The Cuban regime has lost its strategic depth, creating a vacuum that threatens the continuity of governance in Havana.

1. The Strategic Decoupling: Anatomy of the Rupture

To understand the severity of the current crisis, one must analyze the depth of the dependency that has now been violently dismantled. The relationship between Venezuela and Cuba was not a standard bilateral trade agreement; it was an ideological and economic fusion designed to bypass market mechanisms and US sanctions. The dismantling of this architecture by US forces has left Havana with no fallback mechanism.

1.1 The Mechanics of the Caracas-Havana Axis

For over two decades, the survival of the Cuban state was predicated on the “Barrio Adentro” exchange. This agreement, forged by Hugo Chávez and Fidel Castro, structured the transfer of Venezuelan national wealth to Cuba in exchange for human capital. Specifically, Venezuela provided between 30,000 and 50,000 barrels per day (bpd) of crude oil and refined products to Cuba.1 In return, Cuba deployed thousands of doctors, educators, and sports trainers to Venezuela.

Crucially, beneath the surface of this humanitarian exchange lay a vital security cooperation framework. Cuban intelligence agencies, specifically the G2, provided the backbone of the Venezuelan state’s internal security, counter-intelligence, and presidential protection protocols.4 This integration went so far that Cuban advisors were embedded within the command structures of the Venezuelan military and PDVSA, effectively managing the oil flows to ensure Havana’s quota was prioritized over commercial clients or even Venezuelan domestic needs.

The US intervention on January 3, 2026, decapitated this structure. By physically removing the Maduro leadership and targeting the Cuban security apparatus within Venezuela, the US effectively blinded Havana and severed its control over the resource flows.5 The expulsion or neutralization of Cuban personnel in Venezuela means Havana has lost its forward operating base and its leverage over the oil spigots.

1.2 Operation Southern Spear and the Naval Quarantine

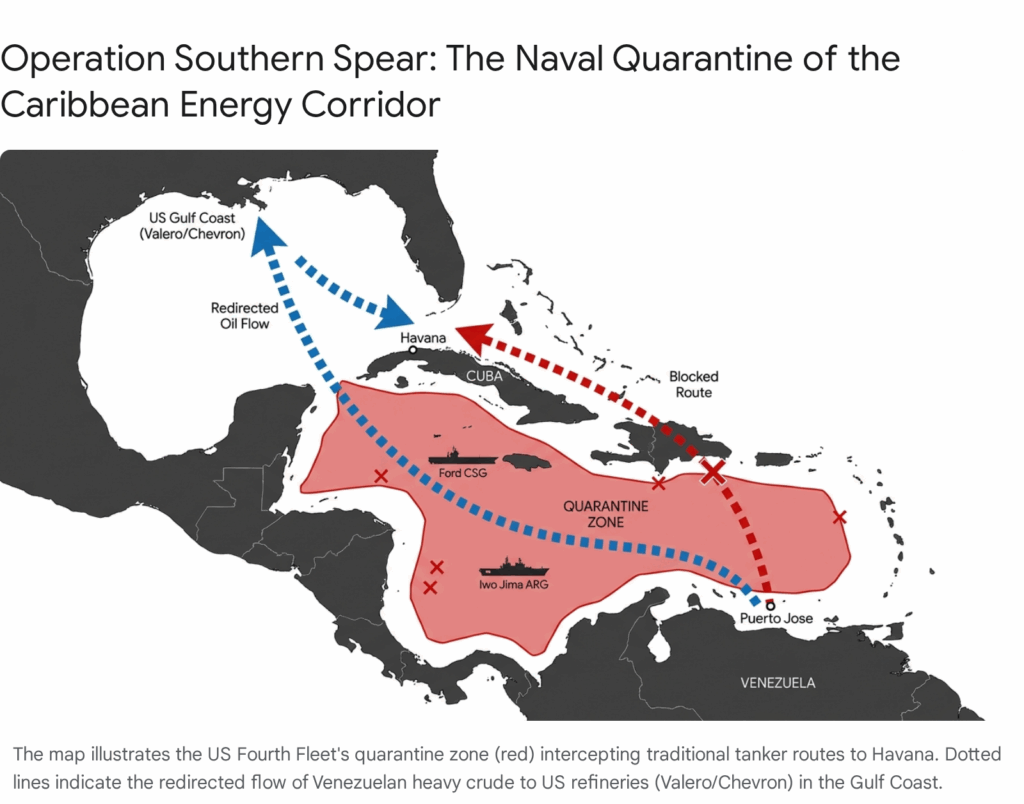

The physical mechanism enforcing this decoupling is Operation Southern Spear. Unlike previous sanctions regimes, which relied on financial designations and Treasury Department lists (OFAC), this operation utilizes the kinetic power of the US Navy and Coast Guard to enforce a physical blockade of energy transfers to Cuba.

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio has explicitly defined the operation as an “oil quarantine,” a terminology that evokes the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis but applies it to energy rather than nuclear armaments.6 The quarantine zone targets the “Dark Fleet”—vessels operating without transponders to evade sanctions—which had been the primary conduit for Venezuelan oil to Cuba in recent years.7

The operational reality of this quarantine is stifling. US naval assets, including the USS Gerald R. Ford Carrier Strike Group and the USS Iwo Jima Amphibious Ready Group, effectively dominate the maritime approaches between Puerto Jose (Venezuela) and Cienfuegos (Cuba).8 Any vessel attempting to run this blockade faces interception, boarding, and seizure. This has created a “risk wall” for global shipping; insurance premiums for voyages to Cuba have skyrocketed, and major insurers have withdrawn coverage for any vessel designated by the US as potentially violating the quarantine.7 The result is that even if Cuba could find a seller, it cannot find a bottom (ship) willing to make the voyage.

1.3 Legal and Commercial Walls

Complementing the naval blockade is a rigid legal framework established by the US provisional authority over Venezuelan assets. The US Treasury has revoked the licenses that previously allowed limited swaps and has instituted a new regime where Venezuelan oil is treated as a strategic asset under US administration.11

Under this new framework, US oil majors (Chevron, ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips) are the authorized custodians of production rehabilitation. These entities operate under strict US law, which explicitly prohibits transactions with Cuba due to the ongoing embargo (LIBERTAD Act). Therefore, there is no legal pathway for a barrel of Venezuelan oil to be transferred to Cuba. The “oil-for-doctors” barter scheme has no legal standing in the new commercial reality of Venezuela. The contracts are void, and the debt is unrecognized. Cuba has transitioned overnight from a privileged partner to a sanctioned pariah in the eyes of the Venezuelan energy sector.13

2. The Energy Asphyxiation: Anatomy of a Collapse

The cessation of Venezuelan oil supplies is a catastrophic event for Cuba’s energy infrastructure. The island’s electrical grid is a chaotic patchwork of Soviet-era thermoelectric plants, floating Turkish power ships, and distributed diesel generators. This entire system was calibrated to run on a specific mix of domestic crude and Venezuelan imports. The removal of the Venezuelan component destabilizes the entire architecture.

2.1 The Mathematics of Deficit

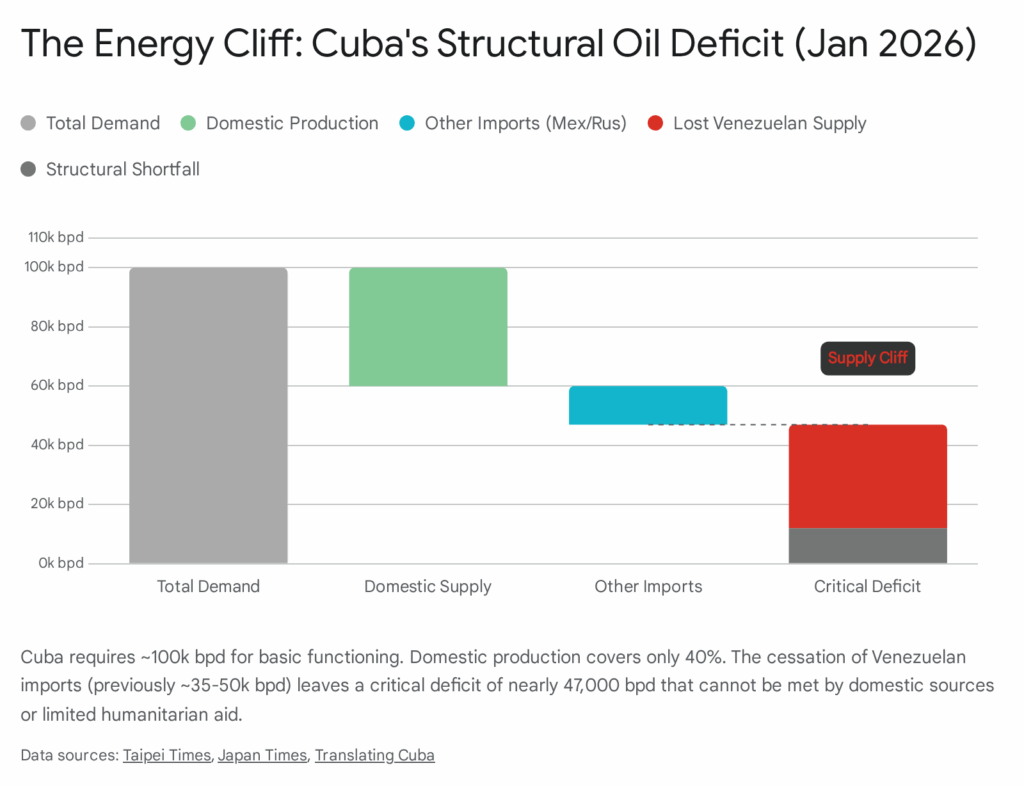

To maintain a minimally functional society—keeping lights on in Havana, running essential industries, and powering hospitals—Cuba requires approximately 100,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day.4 Domestic production, primarily heavy, high-sulfur crude extracted along the northern coast (Varadero/Matanzas belt), contributes roughly 40,000 bpd.3 This leaves a structural deficit of approximately 60,000 bpd.

Historically, Venezuela filled the vast majority of this gap. Even in the diminished years of 2024-2025, shipments averaged 35,000 to 50,000 bpd.1 This imported volume was crucial not just for its quantity but its quality. Venezuelan lighter crudes and refined diesel were essential for blending with the sludge-like Cuban crude to make it combustible in thermoelectric plants, and for fueling the distributed generation network.2

With the US naval blockade reducing this inflow to near zero, the math becomes merciless. The 40,000 bpd of domestic production is insufficient to run the baseload plants at capacity, and it cannot be used in diesel generators or vehicles. The deficit is not 20% or 30%; it is a functional deficit of over 60% of liquid fuel needs, concentrated entirely in the transport and peak-generation sectors.

2.2 The Collapse of Distributed Generation

The most immediate impact falls on the “Distributed Generation” clusters. These are thousands of diesel and fuel-oil generators installed across the island during the “Energy Revolution” of the mid-2000s. They were designed to cover peak demand when the aging thermoelectric plants failed or underwent maintenance.

These generators rely exclusively on imported diesel and fuel oil. The domestic crude is too heavy and sulfurous for them. With the blockade halting refined product shipments from Venezuela, these generators are going offline en masse.15 The result is the loss of the grid’s “shock absorbers.” When a main plant trips offline, there is no backup to pick up the load, leading to frequency instability and total blackouts rather than managed load-shedding.

2.3 The “Zero Diesel” Scenario and Critical Infrastructure

The “Zero Diesel” scenario is the nightmare contingency for Cuban planners. Diesel is the lifeblood of the island’s critical infrastructure backup systems.

- Hospitals: Cuban hospitals rely on diesel generators during blackouts. With 20+ hour blackouts becoming the norm, these generators must run almost continuously. Without fuel deliveries, hospital backup power will fail, leading to immediate loss of life in intensive care units, neonatal wards, and operating theaters.16

- Water Supply: The vast majority of Cuba’s water pumping stations run on electricity or diesel. The blackout prevents electric pumps from filling reservoirs, and the lack of diesel prevents the backup pumps from operating. Over 2 million people were already without reliable water before the intervention.4 This number will likely encompass the entire urban population of Havana and Santiago de Cuba, precipitating a sanitation crisis and the risk of waterborne diseases.

- Cold Chain and Food Preservation: In a tropical climate, the lack of refrigeration is devastating. Households will lose their meager food stocks within hours of a blackout. State cold storage facilities for imported meats and medicines will fail, leading to massive spoilage of strategic reserves.16

3. The Economic Implosion: Sectoral Impact Analysis

The energy crisis is the lead domino in a cascading economic failure. Energy is the primary input for every productive sector of the Cuban economy. The cessation of Venezuelan oil flows renders the current economic model viable.

3.1 Agriculture: The Threat of Famine

Cuban agriculture operates on a model that, while inefficient, is mechanized. Tractors prepare the land, diesel pumps irrigate the fields, and trucks transport the harvest to urban centers.

- Production Collapse: The lack of diesel strikes at the heart of the planting and harvesting cycles. The sugar harvest (zafra), already at historic lows, will likely be abandoned entirely as the fuel cost to cut and transport cane exceeds the value of the sugar produced. Rice production and other staples will suffer similar fates, forcing the population into subsistence farming.

- Distribution Paralysis: The most critical failure point is transport. Even if food is grown or imported as aid, it cannot be distributed. The “Acopio” state distribution system relies on a fleet of aging trucks that require diesel. Without fuel, produce rots in the fields of Artemisa and Mayabeque while the markets in Havana stand empty.4 The breakdown of the rural-urban food supply chain creates the conditions for localized famine.

3.2 Tourism: The Death of the Cash Cow

Tourism has historically been the regime’s primary source of hard currency, funding the import of food and fuel. However, the industry is energy-intensive. Hotels require air conditioning, desalination, and constant lighting to meet international standards.

To shield tourists from the reality of Cuban life, the regime has traditionally ring-fenced energy for the tourism sector, powering hotels with dedicated circuits or generators. The depth of the current fuel crisis makes this impossible. Hotels are now subject to the same shortages as the general population.

- Reputational Destruction: The image of a “tropical paradise” cannot survive reports of 20-hour blackouts, food shortages at buffets, and lack of running water. Cancellations will spike, and new bookings will evaporate.

- Revenue Spiral: The collapse of tourism revenue removes the government’s liquidity. Without tourism dollars, they cannot buy spot-market fuel (even if they could find a seller), which worsens the blackouts, which further kills tourism. This is a classic “death spiral”.4

3.3 The End of Re-export Revenue

A little-known but vital component of the Cuba-Venezuela relationship was the re-export of oil. Venezuela often shipped crude to the Cienfuegos refinery—a joint venture—where it was processed. Cuba would then consume what it needed and export the surplus refined products (diesel, jet fuel) to the international market, keeping the hard currency profit.17

This “middleman” trade was a major source of off-the-books revenue for the regime, often used to fund the military and intelligence services. The US control of PDVSA ends this completely. The Cienfuegos refinery, designed for Venezuelan crude, is now effectively a stranded asset. The loss of this revenue stream defunds the apparatus of the state just as internal security threats are rising.

4. Geopolitical Isolation: The Myth of the Alternative Patron

In previous moments of crisis, Cuba has relied on a geopolitical patron to counter US pressure—first the Soviet Union, then Venezuela. In the current crisis, the regime finds itself isolated. The specific mechanics of the US intervention and the global geopolitical environment preclude an effective rescue by China, Russia, or Mexico.

4.1 The Logistics of Distance and Cost

While Russia and China have issued diplomatic condemnations of the US action 18, material support faces the tyranny of distance and economics.

- Russia: A tanker from Venezuela reaches Havana in 2-4 days. A tanker from Russian ports takes 30 to 45 days. The freight cost for such a voyage is significant. Russia, heavily sanctioned and focused on its war in Ukraine, utilizes a “shadow fleet” for its own oil exports to India and China. Diverting these vessels to supply Cuba for free (or on credit that will never be repaid) is strategically irrational for Moscow. Additionally, Russian crude grades may not be compatible with Cuban refineries designed for Venezuelan heavy sour crude.20

- China: Beijing has historically been pragmatic in its relationship with Venezuela, prioritizing loan repayment over ideological subsidies. With the US controlling Venezuelan assets, China’s priority is negotiating the security of its existing investments with the new US-backed administration, not antagonizing Washington by breaking a blockade to support Havana.19 China’s economic interests lie in stability and access to global markets, which discourages high-risk adventures in the Caribbean.

4.2 The Mexican Dilemma

Mexico, under President Claudia Sheinbaum, initially signaled a willingness to provide humanitarian oil to Cuba.22 However, this support is structurally limited and politically vulnerable.

- US Leverage: The US has enormous economic leverage over Mexico via the USMCA trade agreement and border policies. The Trump administration has explicitly linked Mexican cooperation on migration and drug interdiction to trade stability. Continuing to supply oil to Cuba in defiance of a US “quarantine” places Mexico at risk of secondary sanctions or tariffs.22

- PEMEX Constraints: Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX) is the most indebted oil company in the world. Donating oil to Cuba is domestically controversial and fiscally damaging. Furthermore, Mexican crude production has been declining, limiting the surplus available for export.24

- Operational Risk: Reports indicate that tankers departing Mexico for Cuba have faced US naval scrutiny. The risk of interdiction or being blacklisted by insurers makes the voyage commercially unviable for Mexican vessels.24

5. Regime Stability and Internal Dynamics

The energy and economic crises are rapidly metamorphosing into a political crisis. The Cuban regime relies on two pillars for stability: the “social contract” (subsidized basics in exchange for acquiescence) and the security apparatus. Both are being eroded by the loss of Venezuelan support.

5.1 The Breakdown of the Social Contract

The Cuban population is accustomed to hardship, but the current scenario breaches the implicit limits of the social contract. The “Special Period” of the 1990s had a narrative of shared sacrifice and national defense. The current crisis is viewed increasingly as a failure of management and a result of the regime’s geopolitical gambling.

Protests have evolved from isolated incidents to coordinated expressions of dissent. The “pot-banging” (cacerolazos) protests seen in late 2025 have intensified.25 The demands have shifted from “fix the lights” to broader political slogans (“Freedom,” “Patria y Vida”). As blackouts extend to 20+ hours, the population has little to lose. The fear of repression is outweighed by the existential dread of starvation and darkness.

5.2 The Erosion of Repressive Capacity

The regime’s ability to quell unrest is physically constrained by the fuel shortage.

- Mobility: Police and military vehicles require fuel. In a “Zero Diesel” scenario, the rapid deployment of “Black Beret” special forces to hotspots becomes logistically difficult. The regime may be forced to concentrate forces in Havana, leaving the provinces in a state of semi-anarchy.

- Surveillance: The sophisticated electronic surveillance state built with Chinese and Venezuelan assistance requires electricity. Frequent power cuts blind the digital monitoring systems that track dissent on social media and communications networks.

- Internal Friction: The return of thousands of intelligence officers and military advisors from Venezuela creates a dangerous demographic within the security services.5 These personnel are witnessing the collapse of the project they dedicated their careers to. Discontent within the middle ranks of the military (FAR) and Interior Ministry (MININT)—who are suffering the same blackouts as the civilians—cannot be ruled out.

6. The Migration Event: Mariel 2.0

History demonstrates a direct correlation between economic distress in Cuba and migration surges to the United States. The 1980 Mariel boatlift and the 1994 Rafter Crisis were both precipitated by internal squeezes. The crisis of 2026 is poised to trigger a migration event of similar or greater magnitude.

6.1 The Mechanics of the Surge

The collapse of the grid and the food supply creates a “push” factor of unprecedented intensity. Unlike previous waves where economic aspiration was a driver, this wave is driven by survival.

- State Complicity: In past crises, the Cuban government has used migration as a safety valve, effectively opening the borders to allow the most dissatisfied segments of the population to leave, thereby relieving internal pressure. It is highly probable that the regime will cease patrolling its own coasts, tacitly encouraging a mass exodus.26

- Scale: With nearly 600,000 Cubans having already attempted to leave in recent years, the migration infrastructure (smuggling networks, raft building knowledge) is well-established.27

6.2 US Countermeasures and Humanitarian Crisis

The US response, however, differs from previous eras. The administration has signaled a “closed door” policy, implemented via strict naval interdiction.

- Interdiction Saturation: The US Coast Guard (USCG) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Air and Marine Operations are tasked with holding the line in the Florida Straits. However, these same assets are currently tasked with enforcing the Venezuelan oil quarantine.28 This stretching of resources creates a vulnerability. A mass “swarm” event of thousands of rafts could overwhelm interdiction capacity.

- Humanitarian Dilemma: The intersection of a starving population taking to the sea and a militarized blockade creates the potential for a massive humanitarian disaster in the Straits, with high loss of life and complex search-and-rescue demands placed on US forces.

7. Next Steps for the Venezuelan Oil Industry Under US Control

With the US acting as the de facto provisional administrator of Venezuela’s oil wealth, the path forward for PDVSA involves a rapid reintegration into the Western commercial sphere, explicitly bypassing Cuba.

7.1 The “US Majors” Rehabilitation Strategy

President Trump has outlined a strategy where “very large United States oil companies” will take the lead in rebuilding the sector.14 This is not merely rhetorical; it aligns with the technical realities of Venezuela’s infrastructure.

- Western Capital Re-entry: Companies like Chevron, which maintained a foothold via joint ventures (Petroboscan, Petropiar), are positioned to scale operations immediately. They possess the technical data and the legal standing (via General License 41 modifications) to operate.11

- Infrastructure Triage: The immediate focus will be on the “low hanging fruit”—repairing valves, pipelines, and compression stations in the Orinoco Belt to stabilize production, which currently sits at a fraction of its potential (~1 million bpd vs 3 million bpd historical peak).31

- Supply Chain Rewiring: The most significant shift is the destination of the crude. Venezuelan Merey 16 (heavy/sour) is chemically ideal for the complex refineries of the US Gulf Coast (PADD 3), which were built to process it. The US strategy is to redirect these flows north to Texas and Louisiana, displacing imports from other regions and funding the Venezuelan reconstruction.21

7.2 The Explicit Exclusion of Cuba

The US-led roadmap for PDVSA contains no provision for the continuation of the Cuban subsidy.

- Sanctions Compliance: US oil majors operate under strict adherence to the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) regulations. Any export of Venezuelan crude to Cuba would violate the US embargo (LIBERTAD Act) and trigger severe penalties. Corporate governance at Chevron or ExxonMobil precludes any “off-books” shipments.33

- Commercial Imperative: The provisional Venezuelan government will require immediate cash flow to stabilize the country and pay down debt. Cuba cannot pay for oil. Selling to a non-paying customer while attempting to rebuild a bankrupt national industry is commercially impossible.

- Strategic Intent: The cessation of oil to Cuba is not just a byproduct of the policy; it is a feature. The US administration views the energy starvation of the Castro regime as a strategic benefit, accelerating the possibility of political change in Havana.15

Conclusion

The US intervention in Venezuela and the subsequent control of its oil industry has effectively placed the Cuban regime in a stranglehold. By physically controlling the resource that powered the Cuban economy and policing the waters that transport it, the United States has achieved a level of pressure on Havana that decades of embargo legislation failed to deliver.

The chain of impacts is linear, rapid, and devastating:

- US Control of PDVSA ends the political will to subsidize Cuba.

- Operation Southern Spear physically prevents alternative supplies from reaching the island.

- The Energy Cliff leads to the collapse of the electrical grid and transport sector.

- Economic Paralysis triggers food insecurity and the collapse of the tourism revenue stream.

- Regime Destabilization ensues as the social contract fractures and the security apparatus loses mobility.

The Cuban leadership faces a narrowing set of options, none of which ensure the long-term survival of the status quo. The capture of Nicolás Maduro in Caracas has effectively removed the keystone of the Cuban geopolitical arch, leaving the structure to collapse under its own weight.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- Venezuela’s Oil Industry in Global Market – January 2026 – Lodi 411, accessed January 6, 2026, https://lodi411.com/lodi-eye/venezuelas-oil-industry-in-global-market-january-2026

- Venezuela Sent Twice As Much Oil to the U.S. Than to Cuba in August, accessed January 6, 2026, https://translatingcuba.com/venezuela-sent-twice-as-much-oil-to-the-u-s-than-to-cuba-in-august/

- Maduro ouster leaves Cuba’s wobbling regime without a benefactor, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2026/01/05/world/politics/maduro-cuba-oil-benefactor/

- Maduro ouster leaves Cuban regime without a benefactor – Taipei Times, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2026/01/06/2003850109

- Is Cuba next after Maduro’s capture? – Asia Times, accessed January 6, 2026, https://asiatimes.com/2026/01/is-cuba-next-after-maduros-capture/

- Rubio says US is using oil quarantine to pressure Venezuela, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.indiatribune.com/public/index.php/rubio-says-us-is-using-oil-quarantine-to-pressure-venezuela

- Caribbean Shipping Confronts New Era of Risk After U.S. Raid in Venezuela, accessed January 6, 2026, https://gcaptain.com/caribbean-shipping-confronts-new-era-of-risk-after-u-s-raid-in-venezuela/

- U.S. Navy blockade off coast of Venezuela will continue despite Maduro’s capture – WHRO, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.whro.org/news/local-news/2026-01-04/u-s-navy-blockade-off-coast-of-venezuela-will-continue-despite-maduros-capture

- United States blockade during Operation Southern Spear – Wikipedia, accessed January 6, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_blockade_during_Operation_Southern_Spear

- U.S. Moves to Disrupt Venezuela-Cuba Oil Axis Explained – Discovery Alert, accessed January 6, 2026, https://discoveryalert.com.au/caribbean-energy-enforcement-regulatory-architecture-2025/

- Reversing the Biden Administration, OFAC Announces the Wind Down of Venezuela General License 41 – SmarTrade | Thompson Hine, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.thompsonhinesmartrade.com/2025/03/reversing-the-biden-administration-ofac-announces-the-wind-down-of-venezuela-general-license-41/

- OFAC Terminates License Authorizing Certain Petroleum-Related Activities in Venezuela | Insights | Holland & Knight, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.hklaw.com/en/insights/publications/2025/03/ofac-terminates-license-authorizing-certain-petroleum-related

- Former Chevron executive seeks $2 billion for oil projects in Venezuela, accessed January 6, 2026, https://americanbazaaronline.com/2026/01/06/former-chevron-executive-seeks-2-billion-venezuela-oil-472665/

- What role could the US play in Venezuela’s ‘bust’ oil industry? – The Guardian, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2026/jan/04/venezuela-oil-industry-bust-what-role-could-the-us-play

- Trump Is Convinced That Without Venezuelan Oil the Cuban Regime Will Fall on Its Own, accessed January 6, 2026, https://translatingcuba.com/trump-is-convinced-that-without-venezuelan-oil-the-cuban-regime-will-fall-on-its-own/

- 11 Million Cubans Are Poised to Starve Without Venezuelan Oil. How Many Will We Allow to Die? – Jezebel, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.jezebel.com/cuba-collapse-struggles-power-starvation-food-venezuela-oil-maduro-trump-rubio-miguel-diaz-canel

- ‘Got free oil from Venezuela’: Why Cuba’s collapse looks inevitable after capture of Nicholas Maduro, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.wionews.com/photos/-got-free-oil-from-venezuela-why-cuba-s-collapse-looks-inevitable-after-capture-of-nicholas-maduro-1767531151243

- From Russia to Iran, Venezuela’s allies react to the capture of Nicolas Maduro, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/maduro-capture-world-reaction/mxpdbf7nx

- Trump’s attack leaves China worried about its interests in Venezuela, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/05/venezuela-trump-attack-china-interests-analysis

- With Maduro Gone, Putin Risks Being Pushed Out of the Western Hemisphere, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2026/01/05/with-maduro-gone-putin-risks-being-pushed-out-of-the-western-hemisphere-a91608

- Venezuelan oil output could reach 1.2 million bpd by end of 2026 if sanctions are lifted, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/energy/2026/01/05/venezuelan-oil-output-could-reach-12-million-bpd-by-end-of-2026-if-sanctions-are-lifted/

- Mexican Oil, Cuba and Trump 2.0 – Global Americans, accessed January 6, 2026, https://globalamericans.org/mexican-oil-cuba-and-trump-2-0/

- In the wake of Venezuela, is Mexico next? A perspective from our CEO, accessed January 6, 2026, https://mexiconewsdaily.com/opinion/venezuela-mexico-ceo-perspective/

- 80000 barrels of Mexican oil sent to Cuba: Havana drawn into the US–Mexico clash, accessed January 6, 2026, https://english.elpais.com/international/2025-12-29/80000-barrels-of-mexican-oil-sent-to-cuba-havana-drawn-into-the-usmexico-clash.html

- Cuba on the Brink: Protests and Pot-Banging Over Blackouts, accessed January 6, 2026, https://havanatimes.org/features/cuba-on-the-brink-protests-and-pot-banging-over-blackouts/

- Cuban Immigrants in the United States – Migration Policy Institute, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/cuban-immigrants-united-states-2018

- U.S. Sanctions: A Root Cause of Cuban Migration – The Alliance for Cuba Engagement and Respect (ACERE), accessed January 6, 2026, https://acere.org/migration/

- Coast Guard Migrant Interdiction Operations Are in a State of Emergency | Proceedings, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2023/february/coast-guard-migrant-interdiction-operations-are-state-emergency

- Despite Trump’s hopes, big oil will be wary of rushing back to Venezuela, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2026/jan/05/donald-trump-big-oil-venezuela

- Chevron jumps as Maduro’s fall puts US oil major in pole position for Venezuelan oil, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.tradingview.com/news/invezz:c88ca0cf9094b:0-chevron-jumps-as-maduro-s-fall-puts-us-oil-major-in-pole-position-for-venezuelan-oil/

- What US control over Venezuela’s oil could mean for geopolitics, climate, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.downtoearth.org.in/energy/what-us-control-over-venezuelas-oil-could-mean-for-geopolitics-climate

- Venezuelan Political Transition Reshapes Global Oil Market Dynamics – Discovery Alert, accessed January 6, 2026, https://discoveryalert.com.au/venezuelan-political-transition-oil-dynamics-2026/

- Treasury Issues Venezuela General License 41 Upon Resumption of Mexico City Talks, accessed January 6, 2026, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1127

- Cuban exiles: US control of Venezuelan oil flow to weaken communists’ grasp on power, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.local10.com/news/world/2026/01/05/venezuelan-oil-disruptions-weakens-cuban-communists/