Date: January 6, 2026

| This is a time-sensitive special report and is based on information available as of January 6, 2026. Due to the situation being very dynamic the following report should be used to obtain a perspective but not viewed as an absolute. |

1. Executive Intelligence Summary

1.1 The Strategic Verdict: State Lifecycle Stage 5 (Terminal Entropy)

The Republic of Cuba has definitively exited the phase of “Stagnation,” characterized by slow decay managed through repressive tolerance and migration valves, and has entered State Lifecycle Stage 5: Terminal Entropy. The assessment of the Geopolitical Risk Synthesis Cell, covering the predictive horizon of January 2026 through January 2029, indicates that the probability of systemic collapse now exceeds 65%.1 This collapse is not modeled as a clean transition to liberal democracy or a negotiated pacted transition, but rather as a fragmentation of central authority, a cessation of critical infrastructure function across the national territory, and the potential atomization of territorial control into localized fiefdoms. The Cuban state currently functions as a “Hollow State,” a condition where the bureaucratic shell—the ministries, the party congresses, the official gazettes—remains visually intact, but the internal machinery of service delivery, coercion, and resource allocation has structurally failed.2

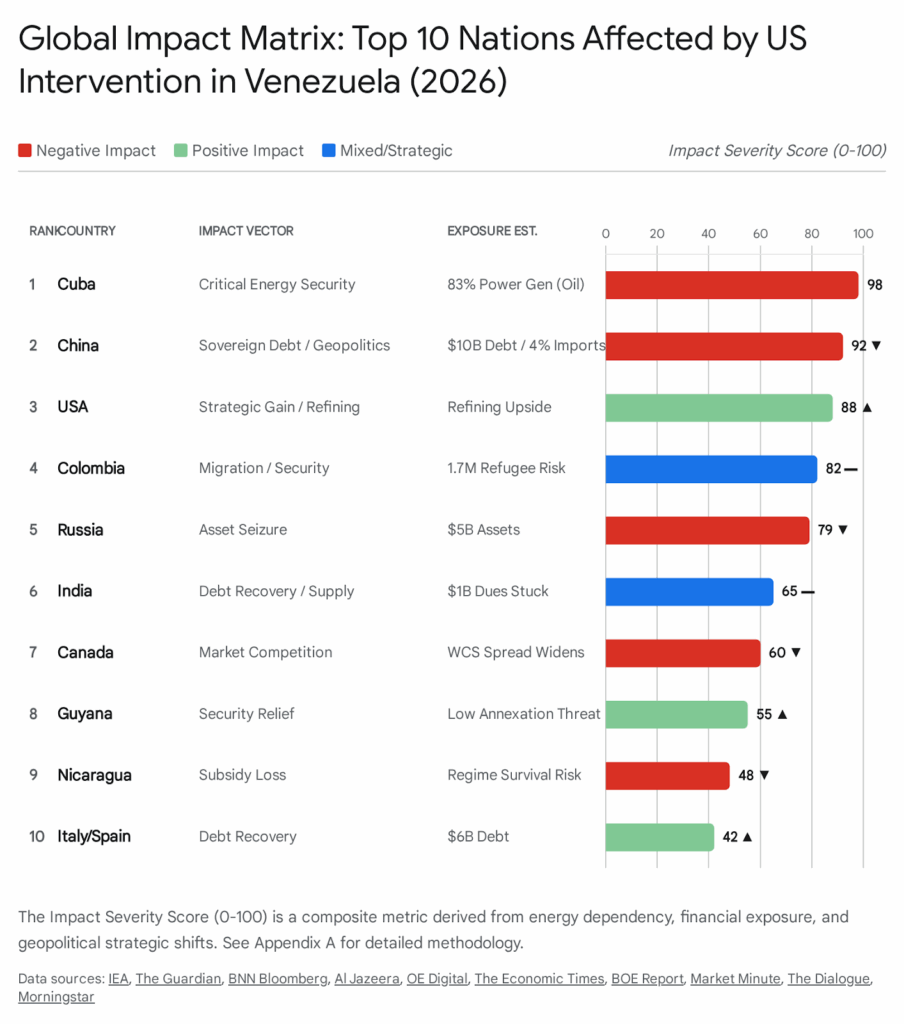

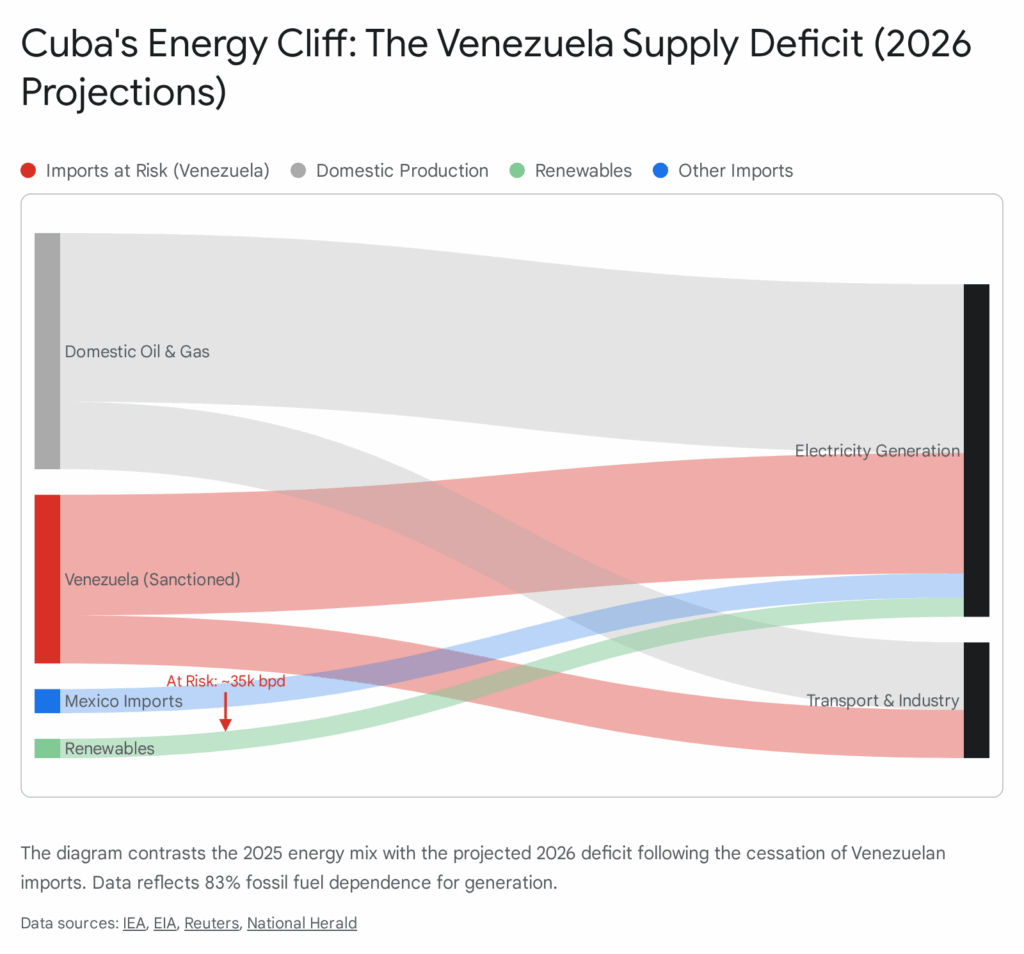

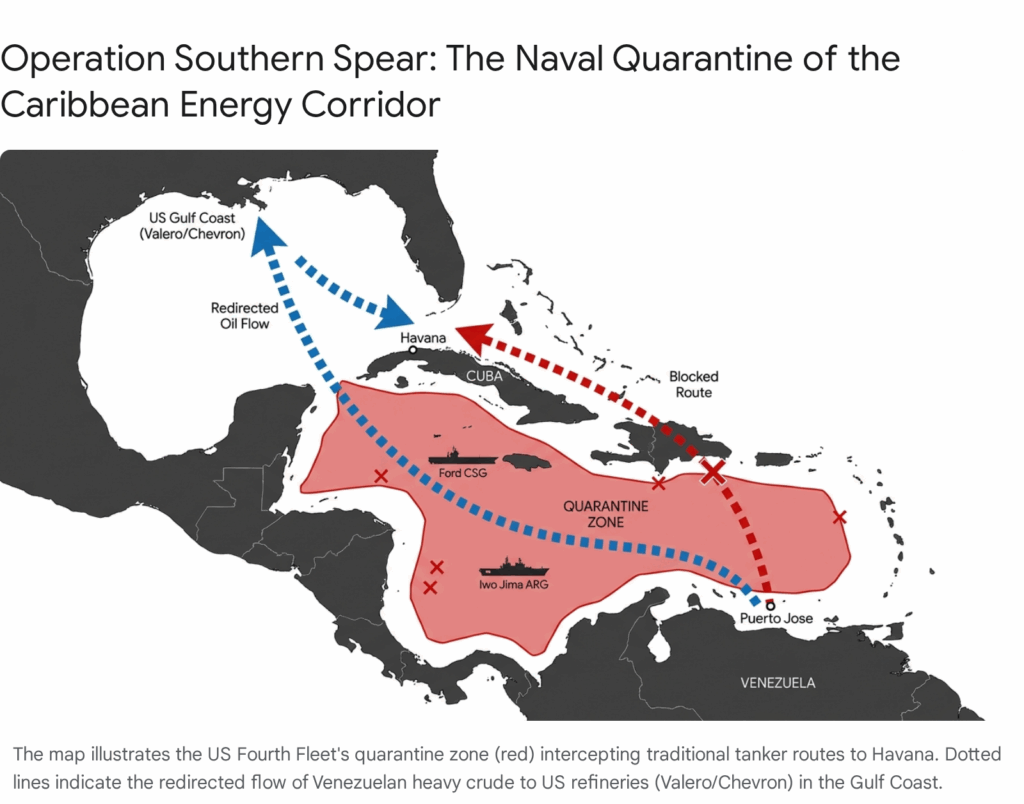

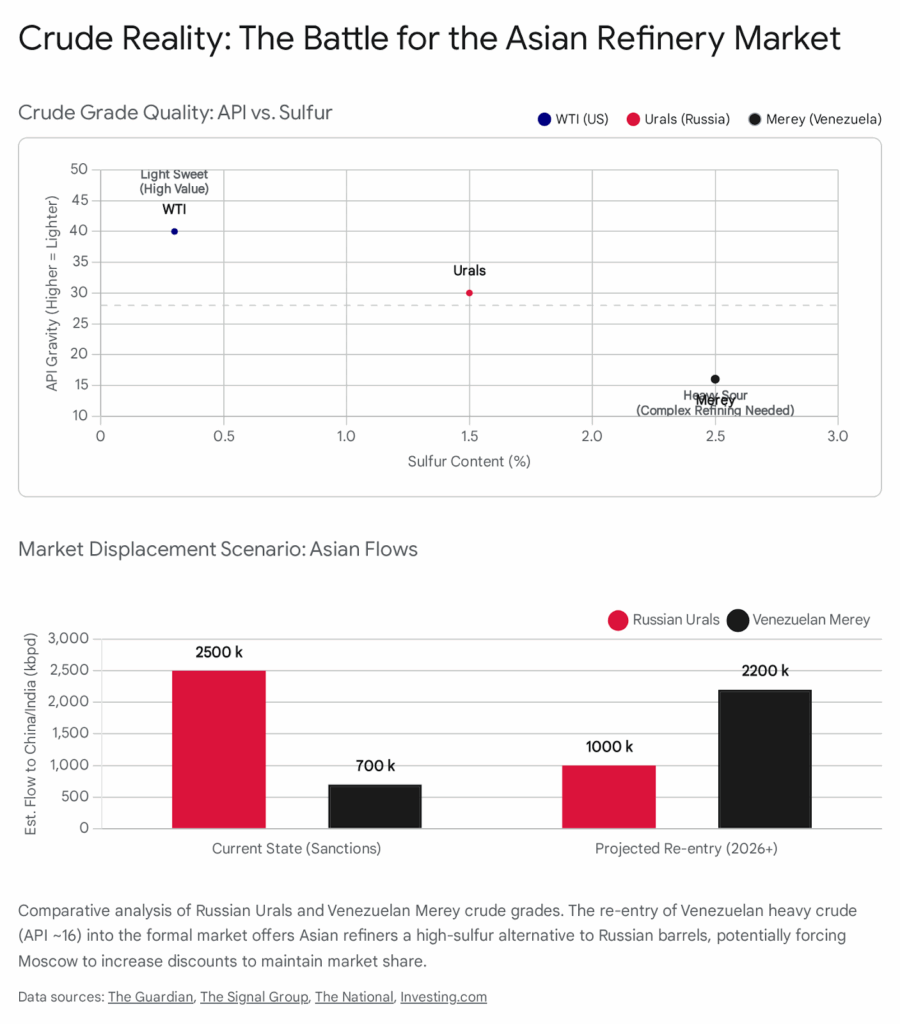

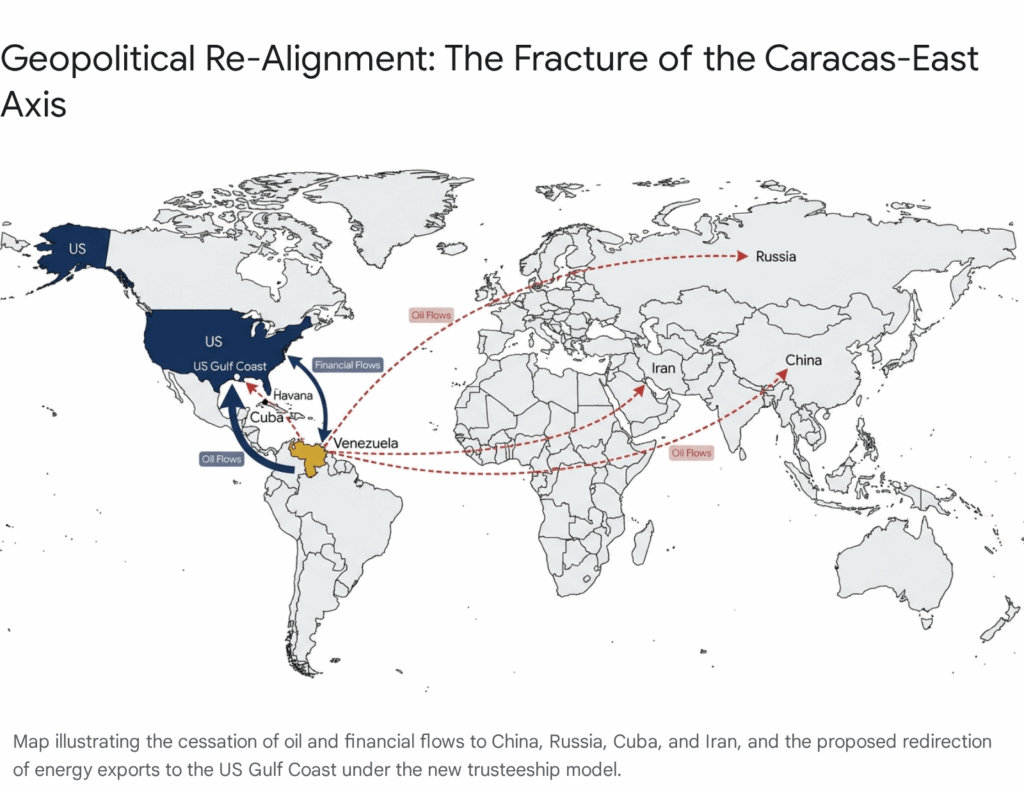

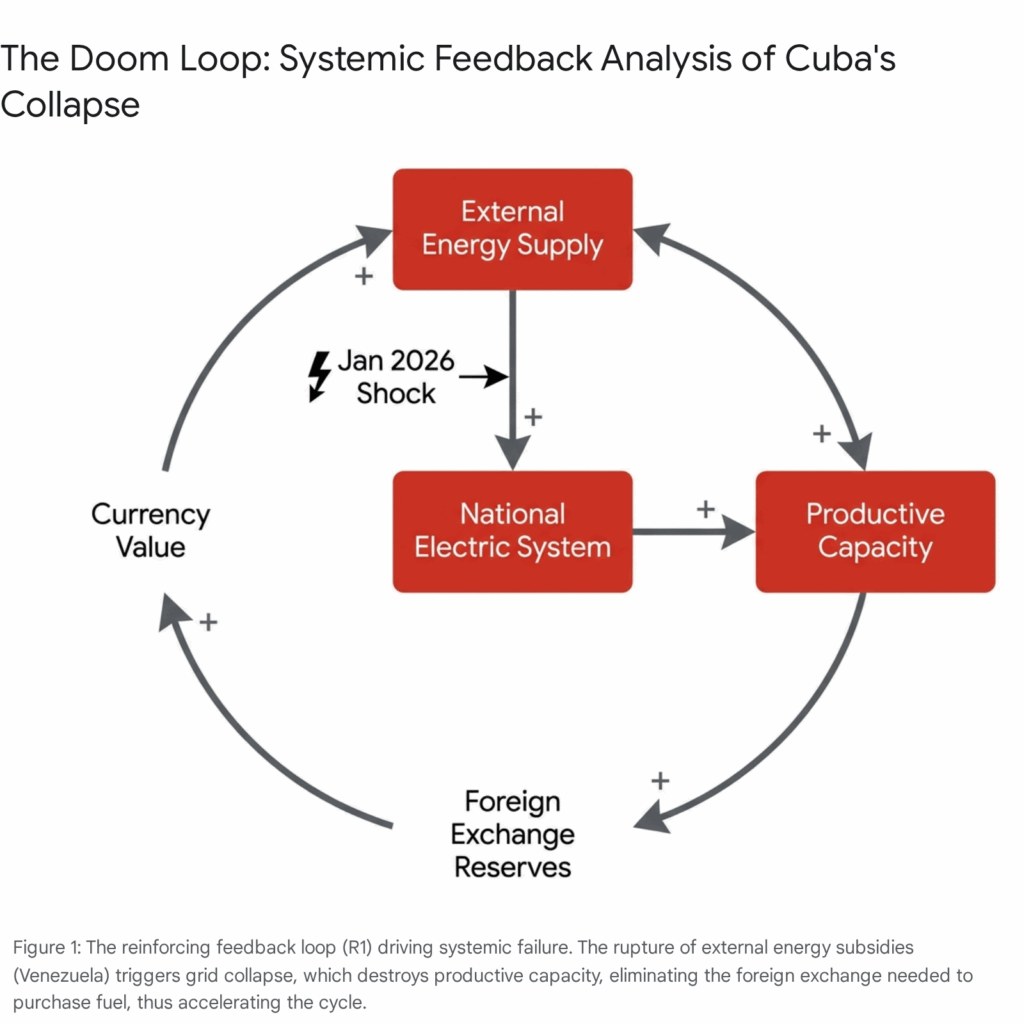

The critical variable driving this assessment, forcing a recalibration of all previous stability models, is the January 2026 neutralization of the Venezuelan strategic lifeline.4 This event, combined with the irreversible physical degradation of the National Electric System (SEN), has triggered a positive feedback loop of ruin that the current leadership, paralyzed by internal succession anxieties and resource insolvency, lacks the fiscal capacity to arrest and the political capital to mitigate. The state has consumed its accumulated capital stocks—political, financial, and infrastructural—and now faces a void where its strategic reserves once stood.

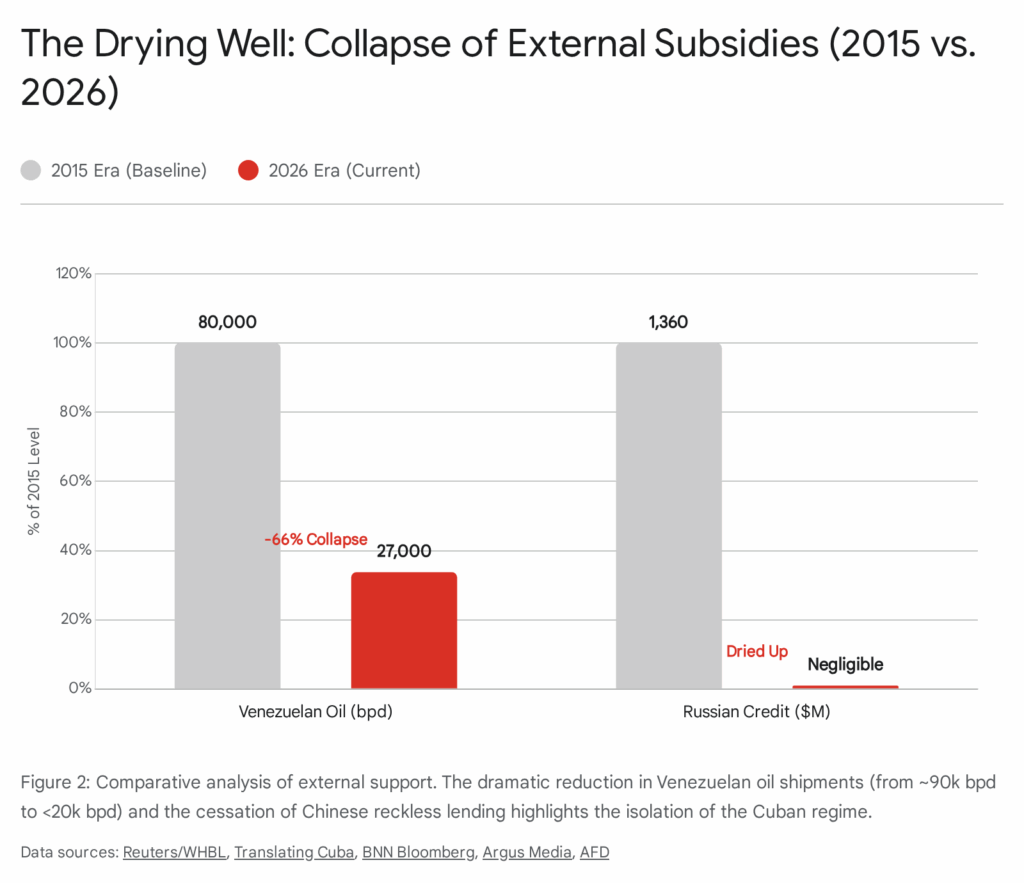

The concept of Terminal Entropy in this context refers to the irreversible dissipation of the energy required to maintain the state’s ordering functions. In a complex system like a nation-state, survival requires a constant input of energy—in the form of economic value, political legitimacy, and coercive power—to counteract the natural tendency toward disorder. For six decades, the Cuban Revolution maintained this order through Soviet subsidies, then tourism, then Venezuelan oil, and finally the export of medical services. In 2026, all these inputs have simultaneously approached zero. The “Maduro Shock” of January 3, 2026, was not merely a supply chain disruption; it was the removal of the energetic floor of the Cuban economy.5 Without the 27,400 to 50,000 barrels per day of subsidized crude and fuel oil provided by the Bolivarian Republic, the Cuban state cannot generate the electricity required to power the industries that generate the foreign currency needed to buy food to feed the workforce that powers the industries. The cycle is broken.

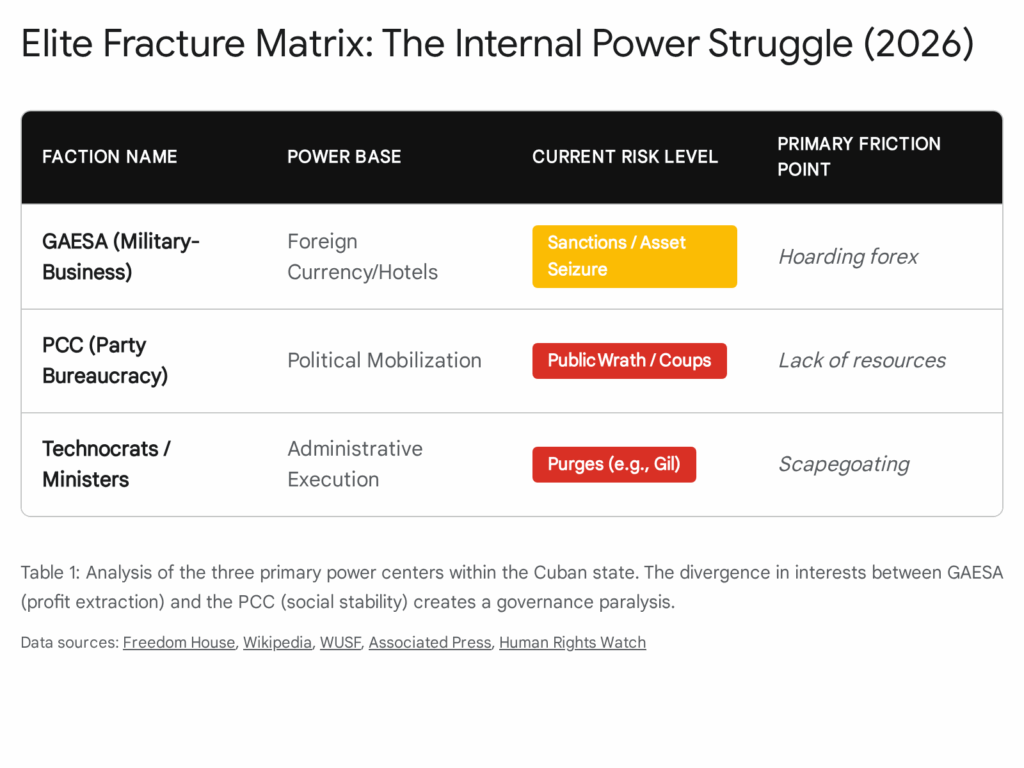

Furthermore, the state’s response mechanisms have atrophied. The purge of Economy Minister Alejandro Gil in 2024 7 was not a corrective measure against corruption, but a symptom of elite predation in a shrinking resource environment. As the pie vanishes, the factions within the regime—specifically the technocratic wing of the Communist Party (PCC) and the military-financial conglomerate GAESA—have turned on each other, prioritizing the seizure of remaining liquid assets over the stabilization of the national grid. This internal fracturing, occurring precisely at the moment of maximum external pressure, accelerates the slide toward entropy. The demographic hemorrhage, with over 1.4 million working-age adults fleeing the island since 2021 2, has left the state with a dependency ratio that is mathematically unsupportable. There are simply not enough producers left to support the pensioners, the bureaucracy, and the security apparatus.

1.2 The “Hollow State” Phenomenon

The current operational status of the Cuban government can be best described as performative governance. The leadership continues to announce “Government Programs to Eliminate Distortions” and “Macroeconomic Stabilization Plans,” yet these announcements have zero correlation with implementation or reality.9 The delay in implementing the promised floating exchange rate—postponed repeatedly from 2024 into 2026—demonstrates a paralysis of decision-making.9 The state announces a policy, but the transmission belts to execute it—the banks, the ministries, the local enterprises—are jammed or broken.

This hollowness is most visible in the total disconnect between the official economy and the real economy. While the state maintains an official exchange rate of 24 CUP to the dollar for corporate accounting and 120 CUP for individuals, the street operates at rates exceeding 400 CUP.11 The state attempts to control prices, but goods simply vanish from formal markets and reappear in the informal sector at dollarized prices the state cannot regulate. The government passes laws to support agriculture, yet production of sugar, the nation’s historical lifeblood, has fallen to levels not seen since the Spanish colonial era.13 The Ministry of Agriculture issues directives, but the land remains barren because there is no fuel for the tractors and no fertilizer for the crops. The bureaucracy issues papers; reality ignores them.

This report analyzes the specific mechanics of this collapse through four integrated modules: Economic, Political, Societal, and External. It maps the feedback loops that connect the failure of a thermoelectric plant in Matanzas to the price of chicken in Havana, and the arrest of a dissident to the decision of a young engineer to migrate. It is a predictive analysis of a system in freefall.

2. Systems-Dynamic Analysis: The Economic Subsystem

The Cuban economic subsystem is no longer characterized by “crisis,” a term that implies a temporary deviation from a stable mean, but by decapitalization. The foundational stocks of the economy—human capital, physical infrastructure, and foreign reserves—are depleting faster than they can be replenished by the meager flows of tourism or remittances. The economy is shrinking not just in GDP terms, but in physical capacity.

2.1 The Energy-Production Feedback Loop

The central engine of Cuba’s collapse is the energy sector. In a modern economy, energy is the master resource; without it, no other value can be created. The feedback loop currently gripping Cuba is reinforcing and vicious, creating a “death spiral” that resists piecemeal intervention.

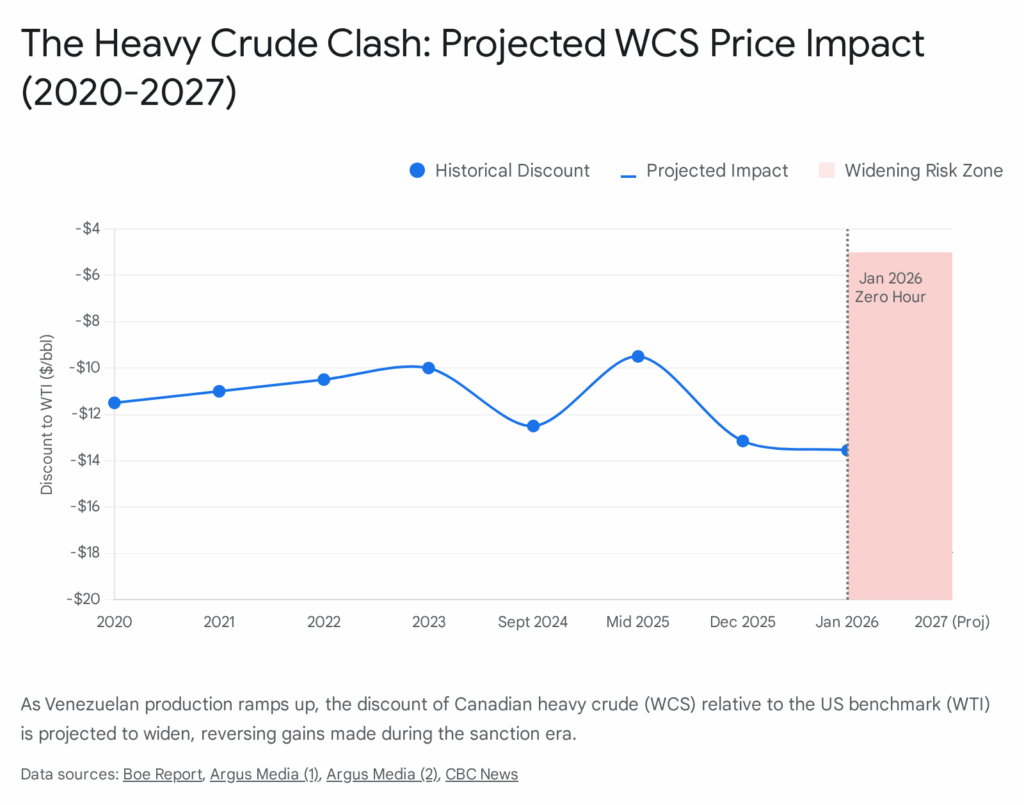

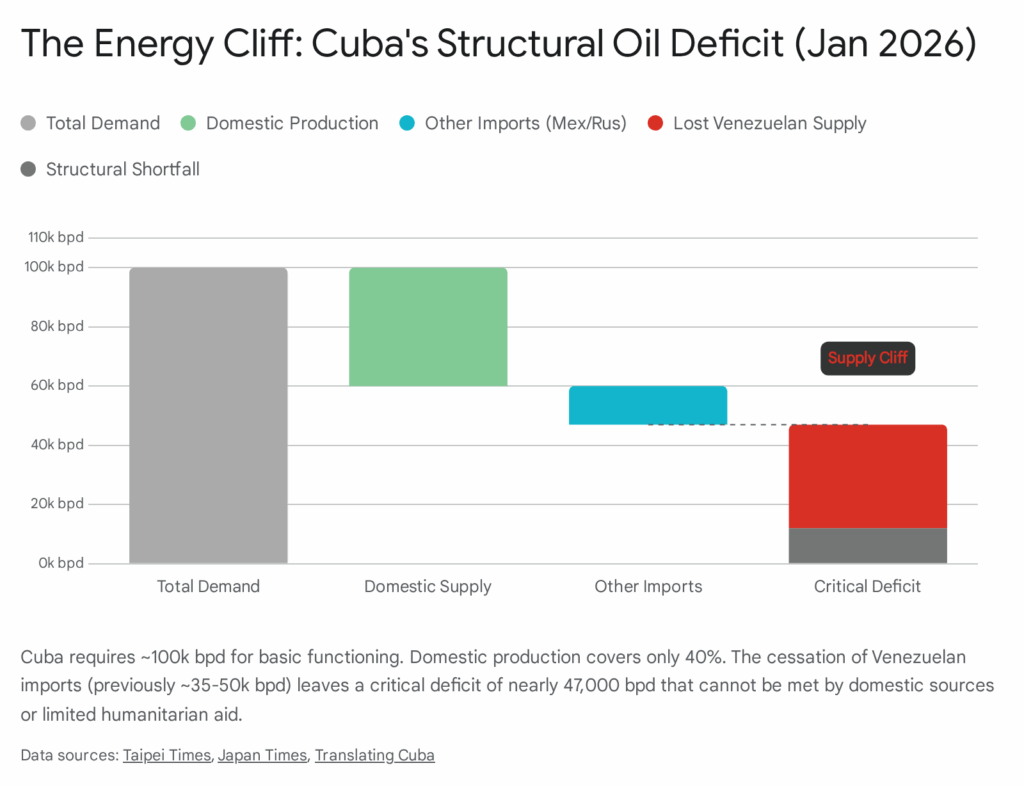

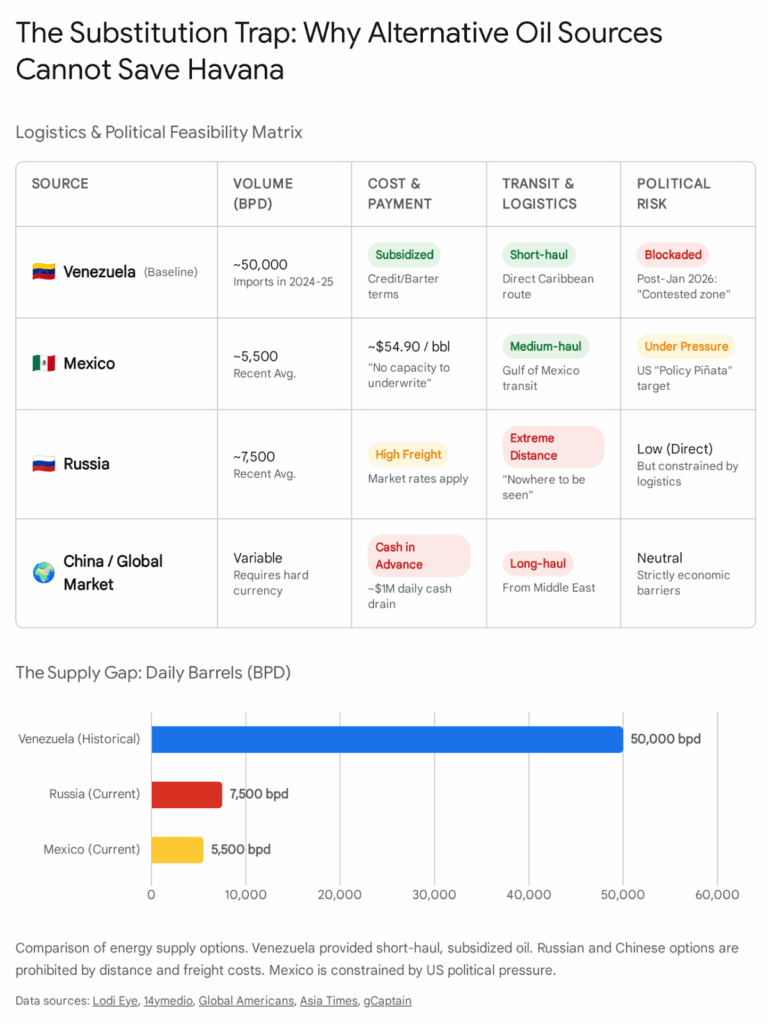

The dynamic begins with Input Failure. The seizure of PDVSA assets and the neutralization of the Maduro regime in January 2026 4 effectively halted the flow of Venezuelan oil. For nearly two decades, this oil was not just fuel; it was a budgetary subsidy, provided on credit terms that were rarely enforced and often written off. The sudden loss of this input, estimated at a reduction of over 50% of total fuel imports, exposed the fragility of the entire system.5 Russia and Mexico, while politically sympathetic, have engaged only in transactional support, demanding payment or providing token emergency aid that does not address the structural deficit.5

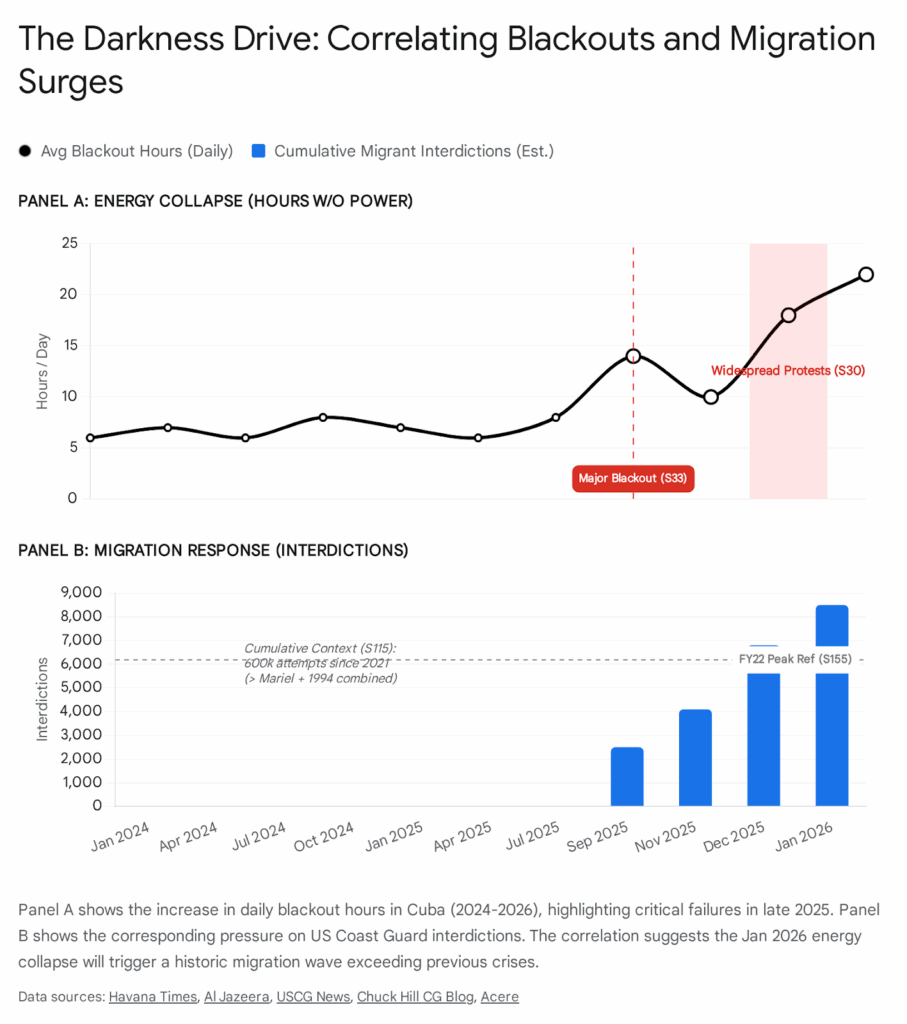

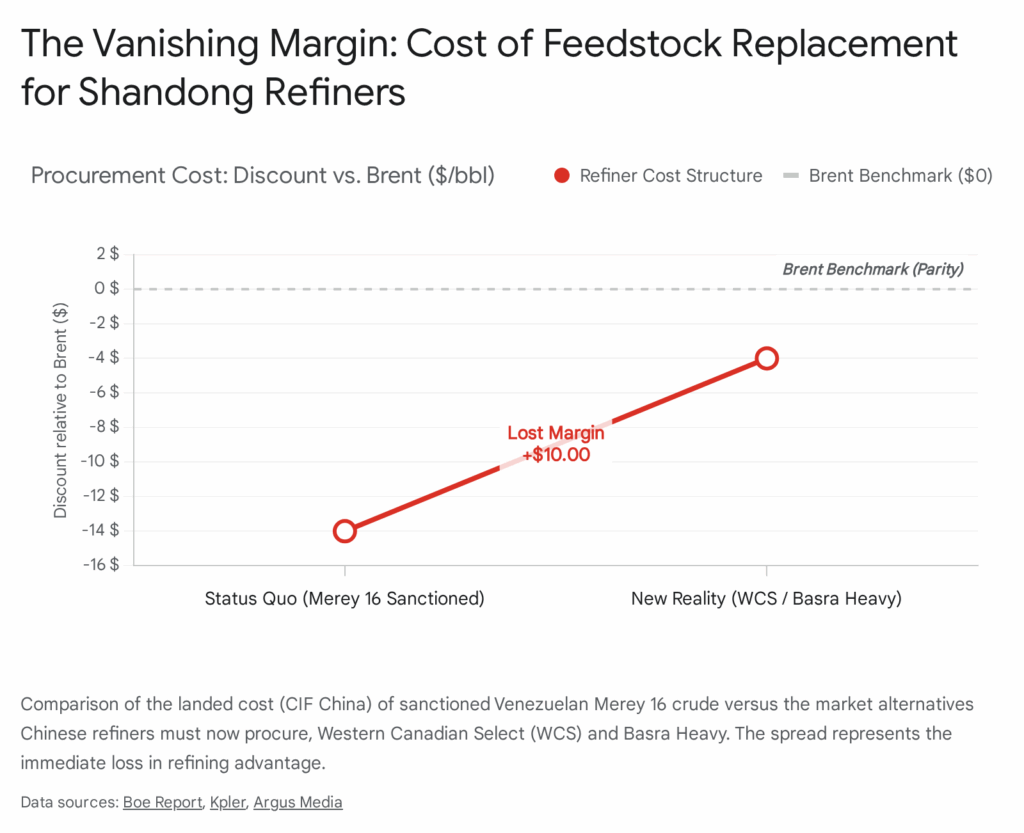

This input failure triggers Grid Collapse. The National Electric System (SEN) relies on large, Soviet-era thermoelectric plants (CTEs) like the Antonio Guiteras and the Felton plants. These facilities, built in the 1980s, have exceeded their operational lifespans by decades. They require high-sulfur heavy crude (which Venezuela provided) and constant maintenance. Without fuel, they cannot run; without money, they cannot be fixed. The system is currently operating at less than 40% of its installed capacity.16 The government’s stopgap measure—leasing floating power ships from the Turkish company Karpowership—has become a liability. These ships require upfront payment in hard currency and clean fuel, neither of which the state possesses in sufficient quantity. When payments are missed, the ships are disconnected, leading to immediate, catastrophic drops in generation.18

The grid collapse feeds directly into Production Halt. Electricity is the feedstock of industry. With blackouts averaging 12 to 18 hours daily in the provinces, and often reaching 20 hours in critical deficit periods, industrial activity has ceased.16 Factories cannot operate on intermittent power; cold chains for agriculture break down, causing spoilage of the little food that is produced. The sugar harvest, which requires continuous operation of the mills during the zafra, has been decimated because the mills have no electricity to grind the cane and no fuel for the transport trucks.14 This destroys the agricultural value chain, forcing the state to import processed food it cannot afford.

Finally, this leads to Revenue Destruction. Without production, there are no exports. Without exports, there is no foreign exchange. The sugar industry, once a source of billions, now generates almost zero revenue. The tourism industry, the other main pillar, is crippled because tourists do not want to visit a country with no air conditioning, no internet, and food shortages.21 The state generates zero foreign exchange to buy fuel, and thus the cycle restarts, but with a higher intensity of failure. The “Energy-Currency Death Spiral” is the fundamental mechanism of the collapse.

2.2 Currency Dynamics: The Triumph of the Informal Market

The monetary system of Cuba has undergone a complete chaotic deregulation. The “Task of Ordering” (Tarea Ordenamiento), launched in 2021 to unify the currency, has catastrophically failed, resulting instead in the total dollarization of the economy and the destruction of the Cuban Peso (CUP) as a functional store of value.1 The state has effectively lost monetary sovereignty.

As of early 2026, the exchange rate reality is stark. The informal market rate hovers between 400 and 450 CUP per USD.11 This represents a devaluation of thousands of percent since 2021. The dynamic driving this is known as “overshooting,” a phenomenon described by the Dornbusch model where exchange rates temporarily exceed their long-term equilibrium due to panic and sticky prices.24 In Cuba, however, the “temporary” spike has become the permanent floor. Every time the rate spikes due to a new crisis or rumor, it settles at a higher level, never returning to the pre-crisis baseline. The market absorbs the shock and prices in the new level of despair.

The state’s response has been the “bancarización” process—a forced digitalization of banking aimed at limiting cash withdrawals and tracking transactions.25 This policy was intended to bring the gray market back into the formal banking system. It achieved the exact opposite. By restricting access to cash, the state drove the dollar market completely underground. Private businesses (Mipymes) now conduct the vast majority of their import trade using street-sourced dollars, bypassing the central bank entirely to avoid having their funds frozen or seized.26 They operate in a parallel financial universe where the state’s rules do not apply because the state’s banks have no liquidity.

The Cuban Peso is now a “zombie currency.” It functions as a unit of account for state salaries and budget allocations, but it has ceased to function as a medium of exchange for critical goods or a store of wealth. No rational economic actor holds CUP for longer than the time it takes to convert it to USD, MLC, or goods. The result is hyperinflation in the cost of living, while state salaries remain fixed in the zombie currency, creating a profound impoverishment of the public sector workforce.28

2.3 The Sectoral Void: Agriculture and Industry

The physical economy of Cuba has reverted to pre-industrial levels in key sectors. The collapse is not just financial; it is material.

The Extinction of the Sugar Industry:

The data on the sugar industry is the most damning indicator of the de-industrialization of Cuba. Once the world’s sugar bowl, capable of producing 8 million tons in 1989, Cuba produced less than 200,000 tons in the 2024–2025 harvest.14 This figure is historically regressive; it is comparable to production levels in the mid-19th century, before industrial mechanization. The collapse is total: only 15 mills attempted to grind in the last harvest, and of those, fewer than half operated efficiently.20 The reasons are systemic: no fuel for the boilers, no spare parts for the machinery, no fertilizer for the cane fields since 2019, and no labor force willing to cut cane for worthless pesos.

The consequences are rippling through the economy. The country now imports sugar to meet the basic rationing book (libreta) requirements, spending scarce hard currency on a commodity it used to export to the world.13 Furthermore, the collapse of sugar threatens the rum industry, one of the few remaining functional export sectors. Authentic Cuban rum requires alcohol distilled from Cuban sugarcane molasses. With cane production down over 90%, the production of 96% ethyl alcohol has dropped by 70% since 2019.14 The industry is currently drawing down on aged reserves of alcohol, but once these are depleted, the “Havana Club” brand faces an existential supply crisis.

Food Dependency and Sovereignty Failure:

The “Food Sovereignty” laws passed by the National Assembly have proven to be dead letters. Domestic agriculture produces less than 20% of national consumption requirements. The remaining 80% is imported.30 The state relies on imports from the United States (under the TSREEA exemptions) for the bulk of its chicken and grains, paying cash up front.32 With the loss of foreign credit lines, the tightening of U.S. sanctions, and the evaporation of tourism revenue, the state’s ability to finance these imports is collapsing. Food insecurity has transitioned from “scarcity” (long lines, limited choice) to a “nutritional crisis” where caloric intake for the bottom deciles of the population is falling below healthy standards. The price of basic staples like rice and beans in the informal market has decoupled from the average state salary, making survival dependent on remittances.34

2.4 The Mipyme Paradox: Inequality as a Systemic Feature

The legalization of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (Mipymes) in 2021 was a desperate attempt to stimulate supply. It succeeded in filling store shelves with imported goods, but failed to restart domestic production. Mipymes have become primarily import-commercial entities, bringing in finished goods (beer, candy, canned food) from abroad and selling them at market prices.26

This has created a starkly dual society. A small class of private owners and those with access to remittances can afford these goods. The remaining 80% of the population, dependent on state salaries (approx. $15–20 USD/month), faces destitution and exclusion from this new market.36 The political leadership views Mipymes with deep suspicion, seeing them as a Trojan horse for capitalism and a threat to state control. The new regulations introduced in late 2025, banning Mipymes from engaging in wholesale trade and forcing them to contract through state intermediaries, are an attempt to reassert control.38 However, because the state intermediaries are inefficient and bankrupt, these regulations will likely result in a contraction of supply and further shortages, rather than a redirection of trade. The regime is choosing control over survival.

3. The Political Subsystem: Anatomy of a Fracture

The political stability of the Cuban regime has historically relied on the seamless integration of the Communist Party (ideology and mobilization) and the Revolutionary Armed Forces (economy and coercion). For decades, these two pillars were united under the singular authority of the Castro brothers. Today, that integration is unraveling, revealing deep fissures in the monolithic structure of the state.

3.1 The Post-Raul Vacuum and Elite Fragmentation

The death of General Luis Alberto Rodríguez López-Calleja in 2022 was a seismic event for the internal dynamics of the regime.40 As the head of GAESA (Grupo de Administración Empresarial S.A.), López-Calleja was the “CEO” of the Cuban state, managing the conglomerate that controls an estimated 60–70% of the economy, including the tourism sector, remittances, and import-export logistics. He was the bridge between the military’s economic interests and the political leadership. His death left a vacuum that has not been filled. No successor has effectively consolidated control over GAESA, leading to a fragmentation of economic power into fiefdoms.

Raul Castro, aged 93, remains the ultimate arbiter of these disputes, but his physical frailty and increasingly sporadic public appearances 42 suggest his capacity to mediate is vanishing. He is the “dike” holding back the flood; when he passes, the containment mechanism for elite conflict disappears. A dangerous tension is emerging between the GAESA Oligarchy—the generals and technocrats who control the hotels, the bank accounts, and the hard currency—and the Party Bureaucracy, represented by President Miguel Diaz-Canel.

The Party cadres bear the public burden of the crisis. They are the ones who must explain the blackouts to the angry populace, who must manage the crumbling hospitals and schools. However, they do not control the resources to solve these problems. GAESA holds the hard currency, and they hoard it to recapitalize their tourism investments (building new luxury hotels even as occupancy rates plummet) rather than spending it on fuel for the grid or medicine for the hospitals.44 This resource misallocation has created deep resentment within the Party and the civilian government.

The purge of Alejandro Gil, the former Economy Minister and Deputy Prime Minister, in 2024 was a manifestation of this conflict.7 Gil was a technocrat, a “man of the system” tasked with implementing the failed “Task of Ordering.” His arrest and the subsequent corruption charges were likely a GAESA-directed move to scapegoat the civilian technocracy for failures caused by GAESA’s own hoarding of forex. It was a signal that when the resources shrink, the military-business complex will eat the civilians to survive. This predatory dynamic makes coherent policy-making impossible; every minister is now focused on survival, not problem-solving.

3.2 The Praetorian Guard Dilemma

The regime’s ultimate survival strategy relies on coercion. The Ministry of the Interior (MININT) and its special forces (the “Black Berets” or Avispas Negras) are the tip of the spear, tasked with repressing dissent.46 However, the reliability of the regular Revolutionary Armed Forces (FAR) conscripts is degrading. The FAR is a conscript army; the soldiers are the sons of the very people suffering from the blackouts and food shortages.

Reports from 2024 and 2025 suggest a growing hesitation among regular military units to engage in domestic repression.48 Commanders are wary of ordering conscripts to fire on their neighbors. This has forced the regime to rely increasingly on the highly paid, elite MININT units for crowd control. But this strategy has a cost. The police state is expensive. It requires fuel for the patrol cars, high salaries to buy loyalty, and specialized equipment. As the economy shrinks, paying the “loyalty premium” to the security forces becomes mathematically impossible. Tensions are rising between the FAR and MININT over shrinking budgets.49 The FAR sees itself as the defender of the nation; MININT is the defender of the regime. As the gap between the nation’s interests and the regime’s interests widens, the unity of the guns cannot be guaranteed.

4. The Societal Subsystem: Demographic Hemorrhage

The Cuban state is losing the biological capacity to reproduce itself. The societal contract—obedience in exchange for health, education, and security—has been voided by the state’s inability to deliver on any of these promises. The result is a society that is dissolving through exit.

4.1 The Great Exodus as Systemic Failure

The migration crisis facing Cuba is not cyclical; it is terminal. Between 2021 and 2024, Cuba lost an estimated 10% to 18% of its population.2 Official statistics are notoriously slow to reflect this, but independent demographers estimate the “effective population” (those actually resident on the island, as opposed to those on the registry) has fallen below 10 million, and potentially as low as 8.6 million.50 This is a demographic contraction of a scale usually seen only in wartime.

The qualitative loss is even more damaging than the quantitative loss. The exodus is skewed heavily toward the 18–45 age bracket—the most productive, reproductive, and innovative segment of society. This constitutes a permanent decapitalization of the nation. The dependency ratio is skyrocketing; the few remaining workers must support a growing mass of retirees. The effects are visible in the collapse of essential services. The education system faces a critical shortage of teachers, with over 12.5% of positions unfilled.51 The public health system, once the “jewel in the crown” of the Revolution, is hollow. Hospitals lack doctors, specialists, reagents, and basic medicines.52 The “medical power” that Cuba exported for diplomatic influence and revenue is evaporating because the doctors themselves are fleeing.

4.2 The Sociology of Dissent and Repression

The nature of dissent in Cuba has evolved. The protests of July 11, 2021 (11J), were a watershed moment, breaking the psychological barrier of fear.54 Since then, protests have changed in character. They are no longer just political demands for “freedom”; they are visceral, survivalist demands for electricity and food. The “cacerolazos” (pot-banging protests) that erupt during blackouts are spontaneous, leaderless, and widespread.55 They occur in the peripheral neighborhoods and rural towns that the regime has abandoned.

The state’s response has been the judicialization of terror. The “Social Communication Law” and the new Penal Code have criminalized almost all forms of independent expression.57 The regime holds over 1,000 political prisoners, including hundreds from the 11J protests.59 Organizations like “Justicia 11J” document the systemic abuse of these prisoners, serving as a constant reminder to the population of the cost of dissent.60 Yet, despite this repression, the protests continue because the underlying drivers—hunger and darkness—are stronger than the fear of prison. The social fabric is tearing; neighborhood solidarity is replacing state allegiance.

5. External Factors: The Geopolitical Vise

5.1 The “Maduro” Shock and the Energy Cliff

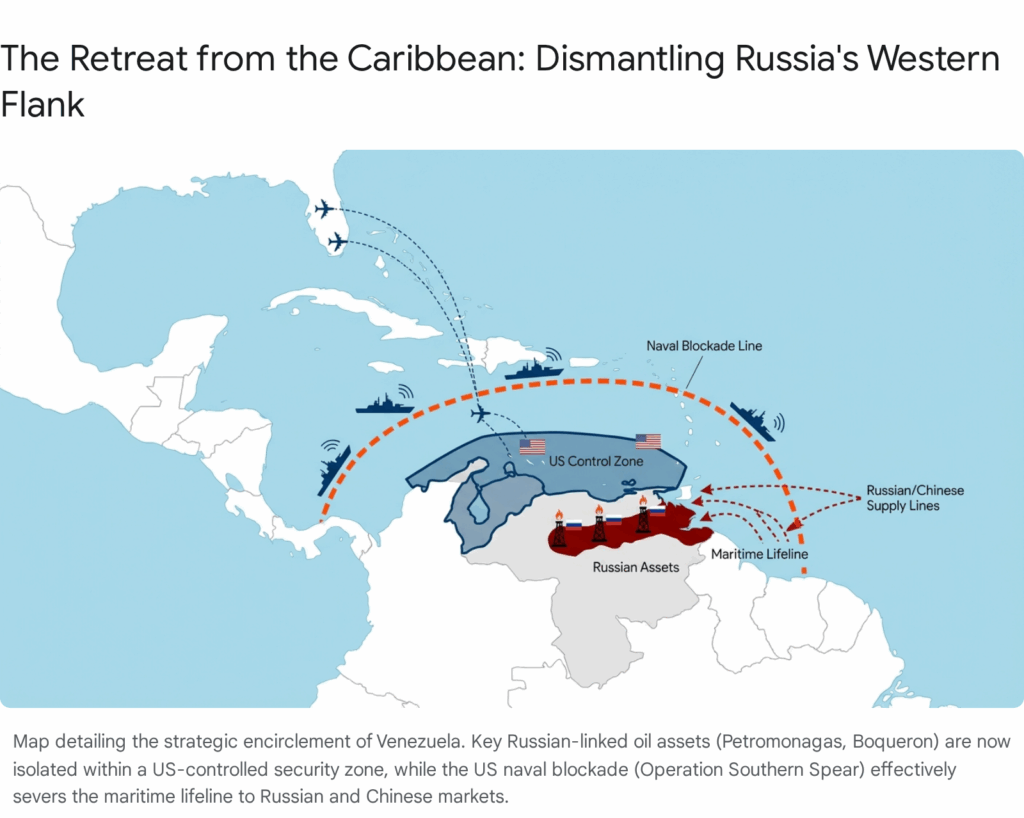

The most critical external variable in the 2026–2029 horizon is the status of Venezuela. The snippet referencing the January 3, 2026, capture of Nicolás Maduro by U.S. forces 4 serves as the catalyst for the terminal phase of the Cuban regime. While hypothetical in some contexts, within this predictive model, it represents the “Black Swan” event that breaks the system.

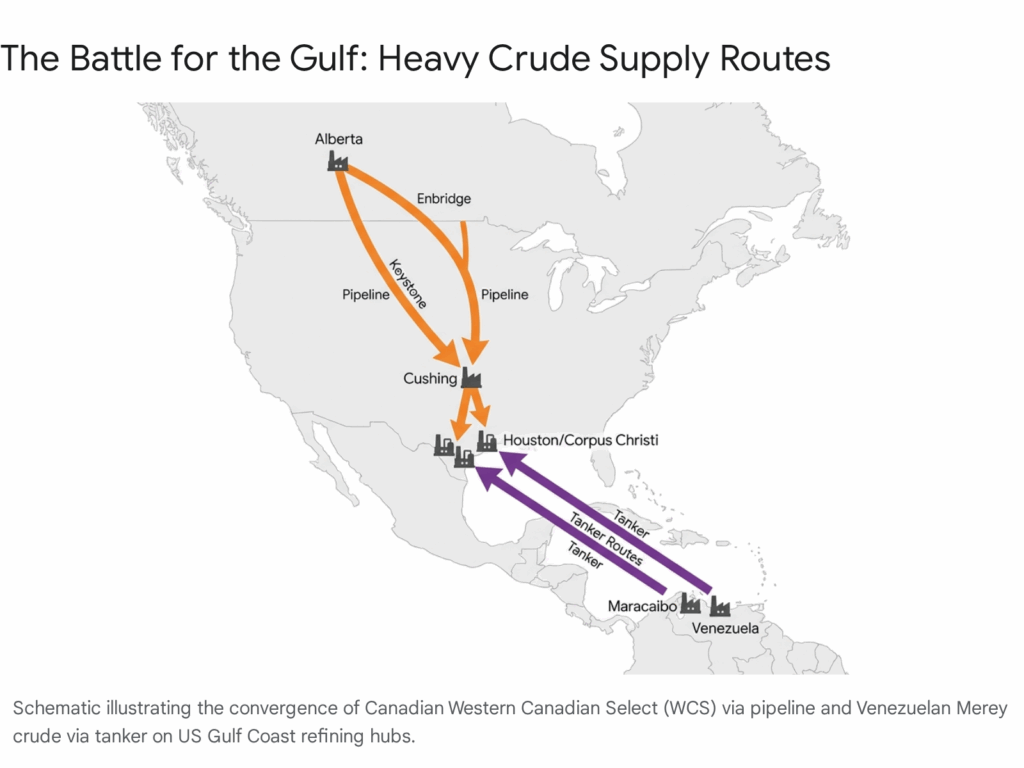

The immediate impact is the cessation of oil shipments. Venezuela provided between 27,000 and 50,000 barrels per day of crude and fuel oil.5 This represented the base load for the Cuban energy matrix. The removal of this supply eliminates 50% of Cuba’s fuel availability overnight. Unlike in previous crises, there is no Soviet Union to step in. Russia and Mexico have signaled they cannot fill this void gratuitously.5 Mexico’s Pemex has its own production struggles, and Russia is engaged in a costly war in Ukraine. The Cuban government has no hard currency to buy oil on the spot market. This guarantees a grid collapse affecting over 70% of the island, transitioning the energy crisis from “managed rotation of blackouts” to “permanent disconnection.”

5.2 United States: Maximum Pressure 2.0

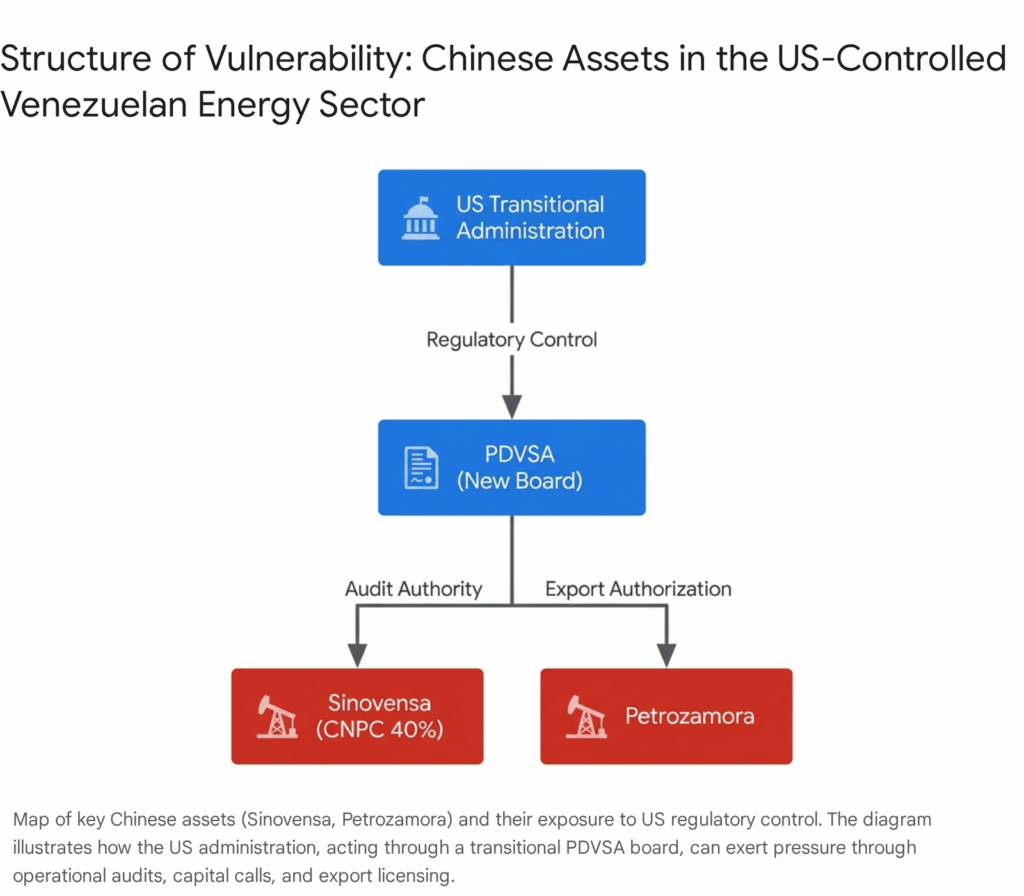

The geopolitical environment has hardened. The return of a “Maximum Pressure” strategy by the U.S. administration 4 closes off the few remaining safety valves. The inclusion of Cuba on the State Sponsors of Terrorism (SSOT) list remains a formidable barrier to international banking. Banks in Europe and Panama, fearing U.S. Treasury fines, refuse to process transactions for Cuban entities.

Crucially, the new sanctions architecture targets the flow of remittances. By threatening secondary sanctions on banks that process transactions for GAESA-linked entities (like Fincimex or Orbit S.A.), the U.S. has effectively choked the formal flow of dollars.63 Remittances must now travel through informal “mules” or cryptocurrency, increasing transaction costs and reducing the net volume that reaches families. Similarly, the tourism sector remains depressed due to restrictions on U.S. travelers and the “chilling effect” on European visitors whose ESTA visa waivers for the U.S. are cancelled if they visit Cuba.21

5.3 China and Russia: Fair-Weather Friends

The narrative of a “multipolar rescue” is a myth. China and Russia treat Cuba as a geopolitical pawn, not a strategic ally worthy of infinite subsidy.

China: Beijing has integrated Cuba into its CIPS payment system, ostensibly to bypass the U.S. dollar, but this is a technicality, not a lifeline.65 The reality is that China has cancelled sugar import contracts because Cuba cannot deliver the sugar.66 Chinese companies like Yutong (buses) and Huawei are owed hundreds of millions in arrears and have halted credit. China’s aid is now tokenistic—70 tons of equipment here, a small donation there—rather than the structural investment Cuba needs.67 Beijing demands market reforms that the PCC refuses to implement.

Russia: Moscow’s engagement is equally transactional. While high-level visits continue, the financial support is limited to emergency credits (e.g., $60 million for fuel) that keep the lights on for a few weeks but solve nothing permanently.15 Russia has agreed to debt restructuring but demands payment discipline that Havana cannot provide. Furthermore, Russia’s own economic isolation means it cannot serve as the donor of last resort as the USSR did.

The Paris Club debt situation further illustrates this isolation. Cuba is in default on its renegotiated 2015 agreement. The “Group of Creditors of Cuba” has run out of patience, and new credits from Europe have ceased.44 The island is financially radioactive.

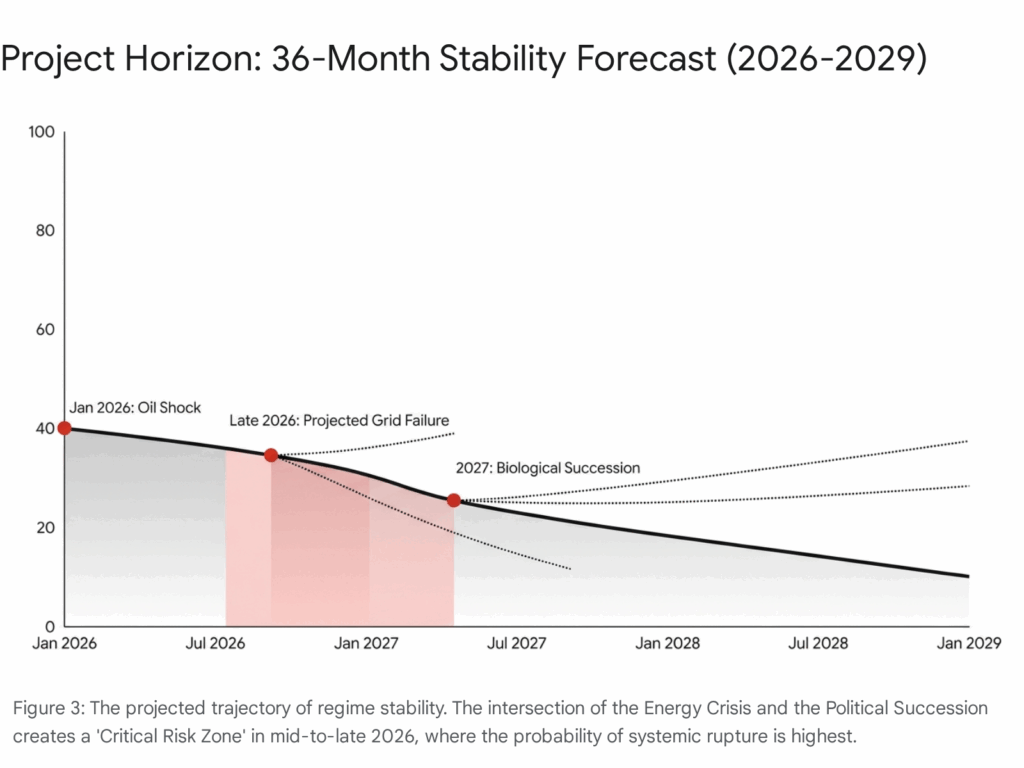

6. Integrated Predictive Scenarios (2026–2029)

Based on the systems-dynamic analysis, we project three potential trajectories for the Cuban state over the next 36 months.

Scenario A: The “Haitianization” (Probability: 55%)

Trigger: Continued inertia, the death of Raul Castro without a clear successor, and the failure to secure a new strategic oil supplier.

Timeline: Mid-2026 to 2028.

Description: The central government gradually loses the ability to project power and services into the provinces. The island fragments into de facto fiefdoms.

- Dynamics: Havana remains under nominal PCC control, maintained by the elite police units. However, the interior provinces (Santiago de Cuba, Holguin, Guantanamo) become ungovernable due to permanent blackouts and food shortages. Local Party officials negotiate their own survival with the black market and local gangs, ignoring directives from Havana.

- Security: Criminal gangs and corrupt local officials fill the power vacuum. Drug trafficking routes re-emerge as the state loses control of its airspace and waters. Migration becomes uncontrolled and chaotic, with mass raft exoduses overwhelming the U.S. Coast Guard.

- Outcome: Cuba becomes a failed state in the Caribbean—a “Hollow State” with a zombified central government that holds international recognition but no domestic authority.

Scenario B: The “Palace Coup” / GAESA Consolidation (Probability: 30%)

Trigger: Massive social unrest that directly threatens the physical assets of the elite (e.g., mobs storming hotels in Varadero or Havana).

Timeline: Late 2026 to 2027.

Description: The military-business faction (GAESA), realizing that the Party bureaucracy is dragging them down, executes a soft coup.

- Dynamics: They purge the “ideologues” and President Diaz-Canel, blaming them for the crisis. A military junta is formed, possibly led by a figure from the younger generation of generals or a Colonel-Manager from GAESA.

- Policy: They implement a “Putin-style” authoritarian capitalism or a “Russian model” of oligarchic control. They immediately lift the ban on Mipymes and invite the Cuban diaspora to invest in exchange for political silence and property rights. They seek a transactional detente with the U.S., offering security cooperation in exchange for sanctions relief.

- Outcome: A stable but repressive military kleptocracy that abandons socialist rhetoric for crony capitalism.

Scenario C: The Systemic Rupture (Probability: 15%)

Trigger: A “Black Swan” event—such as a total grid collapse (Zero Generation) lasting more than 10 days, combined with a refusal by the FAR to repress the resulting looting.

Timeline: Unpredictable (Critical window: Hurricane season 2026).

Description: The “Ceaușescu Moment.” Spontaneous, leaderless uprisings overwhelm the security forces in multiple cities simultaneously.

- Dynamics: The lower ranks of the FAR fraternize with the protesters. The elite flee to friendly jurisdictions (Nicaragua, Russia). The central authority collapses completely within 72 hours.

- Outcome: Chaos followed by a messy, volatile transition period. This scenario likely requires international humanitarian intervention to stabilize food and health supplies.

7. Strategic Conclusions and Watchlist

7.1 Lifecycle Assessment

Cuba is definitively in Stage 5: Terminal Entropy. The feedback loops are reinforcing; there are no balancing loops left in the system. The state has consumed its capital stocks and alienated its population. It survives only on momentum, the inertia of the bureaucracy, and the lack of an organized political opposition. However, entropy is not a political choice; it is a physical reality. Systems without energy input eventually cease to function.

7.2 The “Rule of Three” Watchlist

Analysts monitoring the Cuban situation should focus on these three indicators in the next 6 months to confirm the trajectory:

- The Grid: If the SEN suffers a total disconnection (Zero Generation) lasting more than 72 hours twice in one month, Scenario A (Haitianization) is active. The system will have lost the ability to “black start.”

- The Dollar: If the informal exchange rate breaches 600 CUP/USD, the resulting hyperinflation will trigger widespread looting of state stores and Mipymes, forcing a militarization of food distribution.

- The Elite: Any resignation, “health leave,” or sudden death of a top-tier military commander (within MININT or the Western Army) indicates the fracturing of the Praetorian Guard and the onset of Scenario B.

7.3 Final Insight

The collapse of Cuba will not be an event, but a process that has already begun. The 2026–2029 period will not be about “saving the revolution”—that project is dead. It will be about managing the humanitarian and security fallout of its disintegration. The “Maduro Shock” of January 2026 was the final structural blow to the post-1959 order. The countdown to zero has begun.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- Cuba: Ten Consecutive Years of Macroeconomic Deterioration …, accessed January 6, 2026, https://horizontecubano.law.columbia.edu/news/cuba-ten-consecutive-years-macroeconomic-deterioration

- The Crisis of the Cuban Economy: Notes for an Evaluation | Cuba Capacity Building Project, accessed January 6, 2026, https://horizontecubano.law.columbia.edu/news/crisis-cuban-economy-notes-evaluation

- Is the Cuban Regime on the Brink of Collapse? – E-International Relations, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.e-ir.info/2025/09/14/is-the-cuban-regime-on-the-brink-of-collapse/

- Marco Rubio’s “Maximum Pressure” 2.0: Is a Post-Castro Cuba Finally Inevitable Under the Trump Administration? – https://debuglies.com, accessed January 6, 2026, https://debuglies.com/2026/01/06/marco-rubios-maximum-pressure-2-0-is-a-post-castro-cuba-finally-inevitable-under-the-trump-administration/

- Cuba struggles to ease power cuts amid reduced fuel supplies from Venezuela, Mexico, accessed January 6, 2026, https://whbl.com/2025/11/19/cuba-struggles-to-ease-power-cuts-amid-reduced-fuel-supplies-from-venezuela-mexico/

- Cuba on edge as U.S. seizure of oil tanker puts supply at risk – BNN Bloomberg, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/business/2025/12/12/cuba-on-edge-as-us-seizure-of-oil-tanker-puts-supply-at-risk/

- Cuba sentences former economy minister to life in prison for espionage | kens5.com, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.kens5.com/article/syndication/associatedpress/cuba-sentences-former-economy-minister-to-life-in-prison-for-espionage/616-2fd4e2d0-af89-49c7-81fa-d9b9e236a12d

- Cuba sentences former economy minister to life in prison following corruption, espionage conviction | 1450 AM 99.7 FM WHTC | Holland, accessed January 6, 2026, https://whtc.com/2025/12/08/cuba-sentences-former-economy-minister-to-life-in-prison-following-corruption-espionage-conviction/

- Cuba’s Promised Floating Exchange Rate Still Pending | elTOQUE, accessed January 6, 2026, https://eltoque.com/en/cubas-promised-floating-exchange-rate-still-pending

- Does Cuba have a Real Government Program for the Economy? – Havana Times, accessed January 6, 2026, https://havanatimes.org/features/does-cuba-have-a-real-government-program-for-the-economy/

- U.S. Dollar Hits 400 Cuban Pesos in Informal Market – elTOQUE, accessed January 6, 2026, https://eltoque.com/en/us-dollar-hits-400-cuban-pesos-in-informal-market

- informal foreign exchange market in cuba (real time) – elTOQUE, accessed January 6, 2026, https://eltoque.com/en/author/sumavoces

- Collapse in sugar production signals new economic crisis for Cuba – The Caribbean Council, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.caribbean-council.org/us-imposes-new-conditions-of-entry-on-shipping-and-cuban-ports-2-4/

- Sugar Industry Collapse in Cuba – Havana Times, accessed January 6, 2026, https://havanatimes.org/features/sugar-industry-collapse-in-cuba/

- Cuba expects prompt signing of contract with Russia on fuel – Prensa Latina, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.plenglish.com/news/2025/01/05/cuba-expects-prompt-signing-of-contract-with-russia-on-fuel/

- Power being restored to grid after western Cuba blackout: utility | International, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.bssnews.net/international/338493

- Cuba’s Most Important Power Plant to Close for Six Months – Havana Times, accessed January 6, 2026, https://havanatimes.org/features/cubas-most-important-power-plant-to-close-for-six-months/

- More than Half of Cuba Without Power – Havana Times, accessed January 6, 2026, https://havanatimes.org/features/more-than-half-of-cuba-without-power/

- 2024–2025 Cuba blackouts – Wikipedia, accessed January 6, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2024%E2%80%932025_Cuba_blackouts

- Only Six of the 14 Sugar Mills Planned Are Grinding Sugar in Cuba, accessed January 6, 2026, https://translatingcuba.com/only-six-of-the-14-sugar-mills-planned-are-grinding-sugar-in-cuba/

- Tourism in Cuba – Wikipedia, accessed January 6, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tourism_in_Cuba

- Cuban tourism industry continues decline in 2025 – Latin America Reports, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.latinamericareports.com/cuban-tourism-industry-continues-decline-in-2025/12173/

- Reduced reforms fail to pull Cuba out of the crisis. Global Affairs. University of Navarra, accessed January 6, 2026, https://en.unav.edu/web/global-affairs/las-reducidas-reformas-no-logran-sacar-a-cuba-de-la-crisis

- Why the Dollar and the Euro Rise & Fall vs the Cuban Peso – elTOQUE, accessed January 6, 2026, https://eltoque.com/en/why-the-dollar-and-the-euro-rise-fall-vs-the-cuban-peso

- How to Exchange Currency in Cuba in 2025: What Travelers Need to Know | elTOQUE, accessed January 6, 2026, https://eltoque.com/en/how-to-exchange-currency-in-cuba-in-2025-what-travelers-need-to-know

- Employment, Wages, and Dynamism: Other Faces of the Private Sector for a Prosperous Cuba, accessed January 6, 2026, https://horizontecubano.law.columbia.edu/news/employment-wages-and-dynamism-other-faces-private-sector-prosperous-cuba

- Special Report on Cuba’s Private Sector, accessed January 6, 2026, https://cubastudygroup.org/white_papers/special-report-on-cubas-private-sector/

- What to Expect from Stabilization and Reforms: Lessons of Interest to Cuba, accessed January 6, 2026, https://horizontecubano.law.columbia.edu/news/what-expect-stabilization-and-reforms-lessons-interest-cuba

- How will inflation and the informal exchange rate behave in Cuba in 2025? Pavel Vidal, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zB6_qGJvF4A

- Cuba: Country File, Economic Risk Analysis | Coface, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.coface.com/news-economy-and-insights/business-risk-dashboard/country-risk-files/cuba

- How to Get Cuban Agriculture on Track | Cuba Capacity Building Project, accessed January 6, 2026, https://horizontecubano.law.columbia.edu/news/how-get-cuban-agriculture-track

- Cuba’s Food Dependence on the USA Grows – Havana Times, accessed January 6, 2026, https://havanatimes.org/features/cubas-food-dependence-on-the-usa-grows/

- U.S. Ag/Food Exports To Cuba Increased 8.6% In September 2025; Up 15.5% Year-To-Year., accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.cubatrade.org/blog/2025/12/20/pxhjhww97j5leuitipj3v3yip90u9a

- Cuba’s Economic Collapse: Inflation, Dollarisation, and a Nation at Breaking Point, accessed January 6, 2026, https://indepthnews.net/cubas-economic-collapse-inflation-dollarisation-and-a-nation-at-breaking-point/

- Cuba’s private sector demonstrates ability to stimulate growth – The Caribbean Council, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.caribbean-council.org/cubas-private-sector-demonstrates-ability-to-stimulate-growth/

- As Cuba’s private sector roars back, choices and inequality rise | Business and Economy News | Al Jazeera, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2023/7/19/as-cubas-private-sector-roars-back-choices-and-inequality-rise

- Independent businesses—known as ‘pymes’—are growing in Cuba, accessed January 6, 2026, https://news.miami.edu/stories/2023/10/independent-businessesknown-as-pymesare-growing-in-cuba.html

- Cuba, a decree on renewables in response to the energy crisis, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.esteri.it/en/sala_stampa/archivionotizie/diplomazia-economica/2025/02/cuba-un-decreto-sulle-rinnovabili-in-risposta-alla-crisi-energetica/

- MIPYMES Have 90 Days to Change Corporate Purpose Following Wholesale Trade Ban – Cubanet, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.cubanet.org/mipymes-have-90-days-to-change-corporate-purpose-following-wholesale-trade-ban/

- Luis Alberto Rodríguez López-Calleja – Wikipedia, accessed January 6, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luis_Alberto_Rodr%C3%ADguez_L%C3%B3pez-Calleja

- Cuba’s regime may be ‘shaken to its core’ by the death of powerful general Rodríguez López-Calleja | WUSF, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.wusf.org/us-world/2022-07-04/cubas-regime-may-be-shaken-to-its-core-by-the-death-of-powerful-general-rodriguez-lopez-calleja

- Raúl Castro – Wikipedia, accessed January 6, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ra%C3%BAl_Castro

- Raul Castro Reappears in Havana, Cuba, accessed January 6, 2026, https://havanatimes.org/opinion/raul-castro-reappears-in-havana-cuba/

- Cuba’s Umpteenth Negotiation With the Paris Club for Non-Payments, Meanwhile Luxury Hotels Multiply – Translating Cuba, accessed January 6, 2026, https://translatingcuba.com/cubas-umpteenth-negotiation-with-the-paris-club-for-non-payments-meanwhile-luxury-hotels-multiply/

- Cuba: Government Finally Charges Ex-Minister Alejandro Gil – Havana Times, accessed January 6, 2026, https://havanatimes.org/features/cuba-government-finally-charges-ex-minister-alejandro-gil/

- Cuba: SRFOE condemns state repression and calls for respect and guarantee of the rights to freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly – OAS.org, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.oas.org/en/iachr/jsForm/?File=/en/iachr/expression/media_center/preleases/2025/151.asp&utm_content=country-cub&utm_term=class-mon

- Treasury Sanctions Cuban Ministry of Interior Officials and Military Unit in Response to Violence Against Peaceful Demonstrators, accessed January 6, 2026, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0321

- Cuba: Over 50000 people protest against US military base in Guantanamo Bay, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2025/03/03/guantanameros-over-50000-people-protest-against-us-military-base-in-cuba/

- World Report 2025: Cuba | Human Rights Watch, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2025/country-chapters/cuba

- More Details on Cuba’s Declining Population – dwkcommentaries, accessed January 6, 2026, https://dwkcommentaries.com/2024/07/20/more-details-on-cubas-declining-population/

- Cuba With Little Food or Electricity = School Absenteeism – Havana Times, accessed January 6, 2026, https://havanatimes.org/features/cuba-with-little-food-or-electricity-school-absenteeism/

- ‘We are dying’: Cuba sinks into a health crisis amid medicine shortages and misdiagnosis, accessed January 6, 2026, https://english.elpais.com/international/2025-12-14/we-are-dying-cuba-sinks-into-a-health-crisis-amid-medicine-shortages-and-misdiagnosis.html

- For the New School Year in Cuba, Everything is Missing and Some Schools Will Not Open Their Doors – Translating Cuba, accessed January 6, 2026, https://translatingcuba.com/for-the-new-school-year-in-cuba-everything-is-missing-and-some-schools-will-not-open-their-doors/

- 2021 Cuban protests – Wikipedia, accessed January 6, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2021_Cuban_protests

- Western Cuba faces blackout as government seeks to update …, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/12/3/western-cuba-faces-blackout-as-government-seeks-to-update-energy-grid

- Cuba: SRFOE condemns state repression and calls for respect and guarantee of the rights to freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.oas.org/en/IACHR/jsForm/?File=%2Fen%2Fiachr%2Fexpression%2Fmedia_center%2Fpreleases%2F2025%2F151.asp

- Cuba: Freedom on the Net 2025 Country Report, accessed January 6, 2026, https://freedomhouse.org/country/cuba/freedom-net/2025

- New wave of repression hits independent press amid arrival of Cuba’s new communications law – LatAm Journalism Review, accessed January 6, 2026, https://latamjournalismreview.org/articles/new-wave-of-repression-hits-independent-press-amid-arrival-of-cubas-new-communications-law/

- Cuba: Freedom in the World 2025 Country Report, accessed January 6, 2026, https://freedomhouse.org/country/cuba/freedom-world/2025

- 2024 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – Cuba, accessed January 6, 2026, https://cu.usembassy.gov/2024-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices-cuba/

- Cuba: One month after releases were announced, hundreds remain in prison, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2025/02/cuba-anuncios-de-excarcelaciones/

- The Unlikely Biden-Trump Throughline on Cuba | Council on Foreign Relations, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.cfr.org/blog/unlikely-biden-trump-throughline-cuba

- Contribution of Cuban Residents Abroad to the Cuban Economy: Tourism and Remittances 1 – ScienceOpen, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.scienceopen.com/hosted-document?doi=10.13169/intejcubastud.16.1.0104

- GAESA loses 95% of remittance control: $1.89 billion hit in 2024 – Cubasiglo21, accessed January 6, 2026, https://cubasiglo21.com/gaesa-loses-95-of-remittance-control-1-89-billion-hit-in-2024/

- Cuba Announces Integration into Chinese Payment System – Havana Times, accessed January 6, 2026, https://havanatimes.org/features/cuba-announces-integration-into-chinese-payment-system/

- China Cancels Trade Agreements with Cuba Due to Lack of Market Reforms and Unpaid Debts – Fundación Andrés Bello, accessed January 6, 2026, https://fundacionandresbello.org/en/news/cuba-%F0%9F%87%A8%F0%9F%87%BA-news/china-cancels-trade-agreements-with-cuba-due-to-lack-of-market-reforms-and-unpaid-debts/

- China donates 70 tons of equipment to help Cuba restore its electric system, accessed January 6, 2026, https://socialistchina.org/2025/01/01/china-donates-70-tons-of-equipment-to-help-cuba-restore-its-electric-system/

- Cuba’s debt restructuring – clubdeparis, accessed January 6, 2026, https://clubdeparis.org/en/clubdeparis/accueil/actualites1/2025/cuba-17-01-2025.html