Executive Summary

The geopolitical convergence of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) represents the single most significant restructuring of the international order since the collapse of the Soviet Union. This report, synthesized by a fusion of national security, intelligence, and foreign affairs analysis, provides an exhaustive and nuanced examination of the relationship between Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping. It is designed to serve as a foundational document for understanding the structural mechanics, psychological underpinnings, and strategic vulnerabilities of this authoritarian partnership.

Our assessment moves beyond the superficial “no limits” rhetoric to expose a relationship defined by a complex interplay of mutual necessity and deepening asymmetry. While the alliance is currently resilient—cemented by a shared existential threat perception of the United States—it is fundamentally unbalanced. Russia is rapidly devolving into a junior partner, economically and technologically tethered to Beijing. However, this dependency is managed through a highly personalized dynamic between two leaders whose pathways to power and psychological profiles are both complementary and contradictory.

This report details the historical trajectories of both leaders, dissects their mutual intelligence and military cooperation, analyzes friction points in Central Asia and the Arctic, and forecasts the durability of their axis through the next decade.

Section I: Pathways to Power and Comparative Biographies

To understand the trajectory of the Sino-Russian relationship, one must first dissect the architects behind it. Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping are often grouped as parallel authoritarians, yet their origins, rise to power, and cognitive operational codes differ significantly. These differences shape not only their domestic rule but also the manner in which they negotiate with one another.

1.1 Vladimir Putin: The Reactive Chekist

Vladimir Putin’s worldview is defined by trauma, loss, and the sudden collapse of state power. His leadership style is not that of a strategic architect building a new system from the ground up, but of a tactical disruptor and restorer, shaped fundamentally by his service in the KGB (Committee for State Security) and the chaos of the 1990s.

1.1.1 Origins: The Shadow of Leningrad

Born in Leningrad in 1952, Putin grew up in the post-war ruins of a city that had been besieged and starved. This environment instilled a street-fighter mentality where the first strike is crucial for survival. His entry into the KGB was driven by a desire to belong to the “vanguard” of the Soviet state, the only institution he viewed as competent and pure. His posting to Dresden, East Germany, was pivotal. There, he did not witness the Soviet collapse from the center in Moscow, but from the periphery, watching as the Berlin Wall fell and crowds stormed the Stasi headquarters. His calls to Moscow for instructions went unanswered—a silence he would later describe as the state “paralysis” he vowed never to repeat.

1.1.2 The Rise: From Grey Cardinal to Sovereign Restorer

Putin did not ascend through a rigid party hierarchy in the traditional sense. His rise was catalyzed by the disintegration of the very system he served. Following his return to Russia, he reinvented himself as a bureaucrat in St. Petersburg under Anatoly Sobchak, learning the mechanics of capitalism and municipal governance while maintaining his security connections. His transfer to Moscow and rapid promotion to head the FSB (Federal Security Service) and then Prime Minister in 1999 was less a product of public popularity than elite maneuvering by the “Family” surrounding Boris Yeltsin, who sought a loyal protector.

However, Putin quickly shed the role of a puppet. His rise to the presidency was cemented by crisis—specifically the 1999 apartment bombings and the Second Chechen War. He positioned himself not as a politician, but as a “sovereign restorer,” the guarantor of order against the chaos and humiliation of the Yeltsin years. He leveraged his security credentials to consolidate authority, rapidly curtailing the influence of the oligarchs who had thrived in the vacuum of the 1990s.1

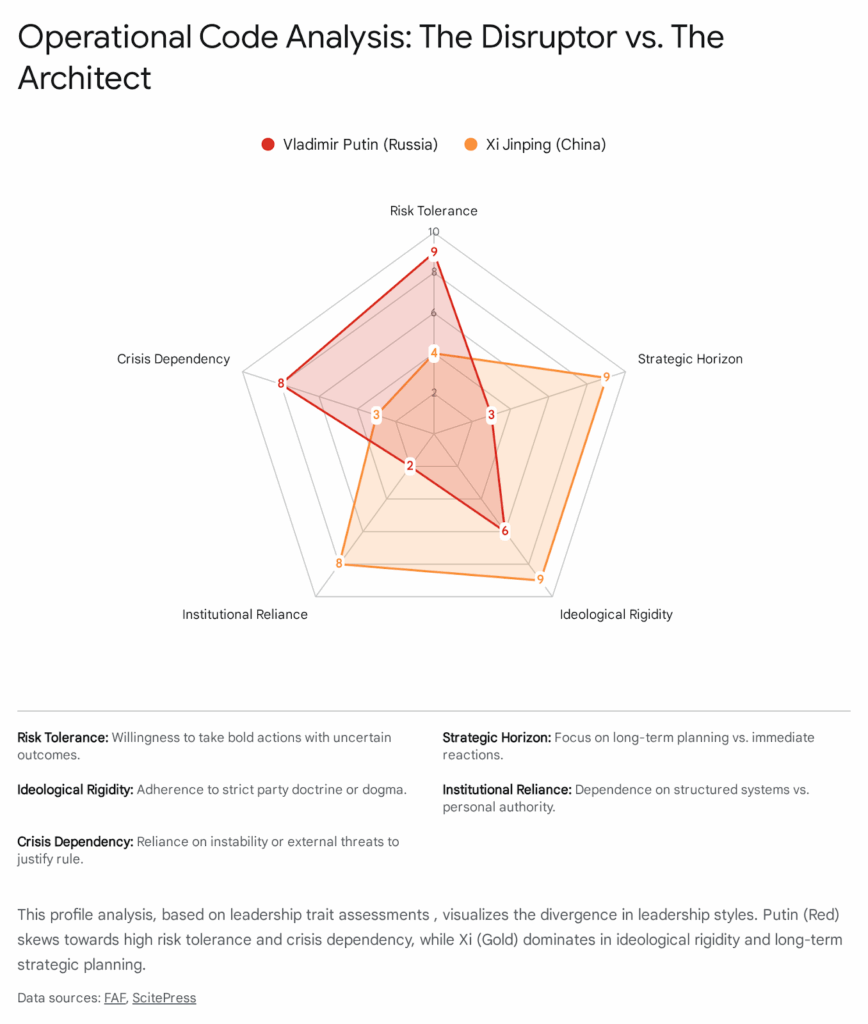

1.1.3 Psychological Profile: The Risk-Acceptant Tactician

Intelligence assessments classify Putin as a “reactive” and “risk-acceptant” leader. His operational code is characterized by a high need for power and a belief that the political universe is inherently hostile. Unlike leaders who seek to reshape the world through ideology, Putin seeks to control it through the manipulation of instability.

- Crisis Exploitation: Putin thrives on instability. His decision-making often involves creating a crisis (e.g., Georgia 2008, Crimea 2014, Ukraine 2022) to force adversaries to the negotiating table on his terms. This reflects a “reactive” leadership style where he assesses the possibilities within a situation and acts to maximize immediate leverage.2

- Accommodative vs. Combative: While he can be accommodative in face-to-face negotiations to build consensus—a trait observed in his interactions with non-Western leaders—his underlying mistrust of others’ motives drives him toward unilateral action. He views compromise as a temporary tactical pause rather than a strategic end state.2

- Historical Grievance: His narrative is retrospective, focused on correcting historical wrongs and restoring Soviet-era prestige. This makes his foreign policy revanchist and often emotional, driven by a desire to reverse the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century.”

1.2 Xi Jinping: The Disciplined Ideologue

In stark contrast, Xi Jinping is a “princeling,” the son of revolutionary veteran Xi Zhongxun. His rise was not an accident of chaos but a calculated, decades-long ascent through the intricate bureaucracy of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). If Putin is the survivor of a collapsed empire, Xi is the heir determined to prevent his own empire’s collapse.

1.2.1 Origins: The Crucible of the Yellow Earth

Born on June 15, 1953, Xi’s formative experience was not the halls of power, but the chaos of the Cultural Revolution.3 Unlike Putin, who was part of the security apparatus, Xi was a victim of the state’s ideological purity spirals. His father was purged, and Xi was sent to the countryside in Shaanxi province to live in a cave and perform manual labor for seven years. Rather than rejecting the Party that persecuted his family, Xi doubled down, determining that the only way to be safe was to become the Party itself.1 This experience instilled a deep resilience and a conviction that chaos (luan) is the ultimate enemy of the state.

1.2.2 The Ascent: A Calculated Climb

Xi’s career advanced through provincial governance (Fujian, Zhejiang, Shanghai), where he cultivated a reputation for pragmatism, economic management, and a low profile that threatened no one. This allowed him to emerge as the consensus candidate in 2012. However, upon ascending to the role of General Secretary, he revealed his true ambition. Inheriting a system designed by Deng Xiaoping to prevent personalistic rule, Xi systematically dismantled collective leadership norms. He launched a sweeping anti-corruption campaign that doubled as a political purge, eliminating rivals like Bo Xilai and Zhou Yongkang, and centralized authority under his status as the “core leader”.1

1.2.3 Psychological Profile: The Strategic Controller

Xi exhibits a “dominant-conscientious” personality composite. Unlike Putin’s reactive tactical maneuvering, Xi is a strategic planner obsessed with control, ideology, and legacy.

- Systemic Control: Xi believes in the absolute centrality of the Party. His “deliberative style” is evident in his long-term projects like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and his ruthless, methodical restructuring of the PLA. He prioritizes ideological conformity and party discipline over individual freedoms or short-term economic gains.1

- Ideological Rejuvenation: Xi’s mandate is framed around the “Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation.” He is future-oriented, focused on displacing the U.S. order not through chaos, but through the sheer gravity of China’s comprehensive national power. His rhetoric emphasizes global cooperation and a “community of common destiny,” masking a Sino-centric worldview.4

- Confidence: Xi displays high self-confidence and a belief in the historical inevitability of China’s rise, viewing the West as being in terminal decline. This confidence contrasts with Putin’s insecurity; Xi operates from a position of rising strength, while Putin operates from a position of managed decline.4

1.3 Convergence of Divergent Paths

Despite their different origins—one a KGB case officer, the other a Party aristocrat—their paths have converged on a shared method of governance: the exploitation of institutional weakness to restore national dignity. Both tapped into public disillusionment: Putin with the chaos of the 1990s, and Xi with the corruption and ideological drift of the Hu Jintao era. They both frame themselves as indispensable saviors of their respective nations.1

However, the nature of their authority differs fundamentally. Putin’s power is personalistic, fragile, and tied to his physical survival. Xi’s power is systemic, embedded in the revitalized machinery of the CCP. This distinction is critical for forecasting the durability of their respective regimes and the alliance itself.

Section II: The “No Limits” Dynamic: Mutual Perceptions and Personal Chemistry

The relationship between Moscow and Beijing has evolved from the ideological hostility of the Sino-Soviet split to a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” This transformation is not merely geopolitical but deeply personal, anchored in the rapport between Xi and Putin. Understanding how they view each other requires peeling back the layers of diplomatic niceties to reveal the calculations of power.

2.1 The “Best Friend” Narrative

Since Xi’s ascension in 2012, the two leaders have met more than 40 times—a frequency unmatched by their interactions with any other world leader.6 Their public displays of affection are well-documented and choreographed to signal unity to the West. This personal diplomacy serves as the ballast for the broader state-to-state relationship.

- Birthday Diplomacy: In 2019, Putin presented Xi with a box of Russian ice cream for his 66th birthday, and they toasted with champagne. Xi has publicly called Putin his “best friend and colleague,” a designation he has not bestowed upon any other leader. Putin reciprocates with similar language, often emphasizing their shared values.7

- Shared Grievances: Their bond is cemented by a shared “P-1 Belief” (beliefs about the political universe): the view that the U.S. hegemony is a threat to their regime survival and that the global order must be multipolar. Research utilizing operational code analysis indicates that while their strategies differ, their fundamental diagnosis of the world’s problems is identical: American containment.9

2.2 Private Mistrust and the “Junior Partner” Anxiety

Beneath the toasts and ice cream lies a bedrock of historical suspicion and widening asymmetry. The “No Limits” partnership is, in reality, a partnership with carefully managed boundaries.

2.2.1 The Russian View: Fear of Vassalization

Putin is acutely aware of the shifting power balance. Russia’s economy is a fraction of China’s, and its reliance on Beijing for trade and technology is deepening. This creates a palpable anxiety within the Kremlin about becoming a resource appendage to the PRC.

- Sovereignty Concerns: Putin’s assertion that “there is no leader or follower” in the relationship is analyzed by intelligence agencies not as a statement of fact, but as an indirect rebuke to the growing perception that Russia has become China’s “little brother.” Prominent commentators like Deng Yuwen have noted that Putin acts to remind China that it cannot manipulate Russia at will.10

- Managing the Optic: The Kremlin carefully manages domestic propaganda to portray the relationship as a partnership of equals, suppressing narratives that highlight Russia’s economic subservience. However, elite surveys and leaked reports suggest a lingering racial and civilisational mistrust of China among the Russian security establishment, rooted in fears of demographic encroachment in the Far East.11

2.2.2 The Chinese View: Strategic Utility vs. Liability

For Xi, Putin is a useful but volatile asset. Russia serves as a “battering ram” against the Western security order, drawing U.S. resources to Europe and away from the Indo-Pacific. However, Beijing views Moscow’s decision-making as erratic and occasionally dangerous to Chinese interests.

- The Ukraine Shock: Intelligence indicates that Putin likely misled Xi regarding the scale and duration of the Ukraine invasion during their meeting at the 2022 Winter Olympics. The subsequent failure of the Russian military to secure a quick victory was viewed in Beijing as a miscalculation that exposed China to secondary sanctions risks and unified the West—an outcome Xi sought to avoid.13

- Arrogance and Decline: Chinese elites and the public have historically viewed Russia with a mix of admiration for its defiance and disdain for its economic decline. Recent sentiments suggest a shift where Chinese nationalists view the U.S. and West as arrogant, leading to sympathy for Russia. However, elite discourse increasingly regards Russia’s actions as reckless and sees the country’s long-term trajectory as one of inevitable decline, fueling a sense of Chinese superiority.5

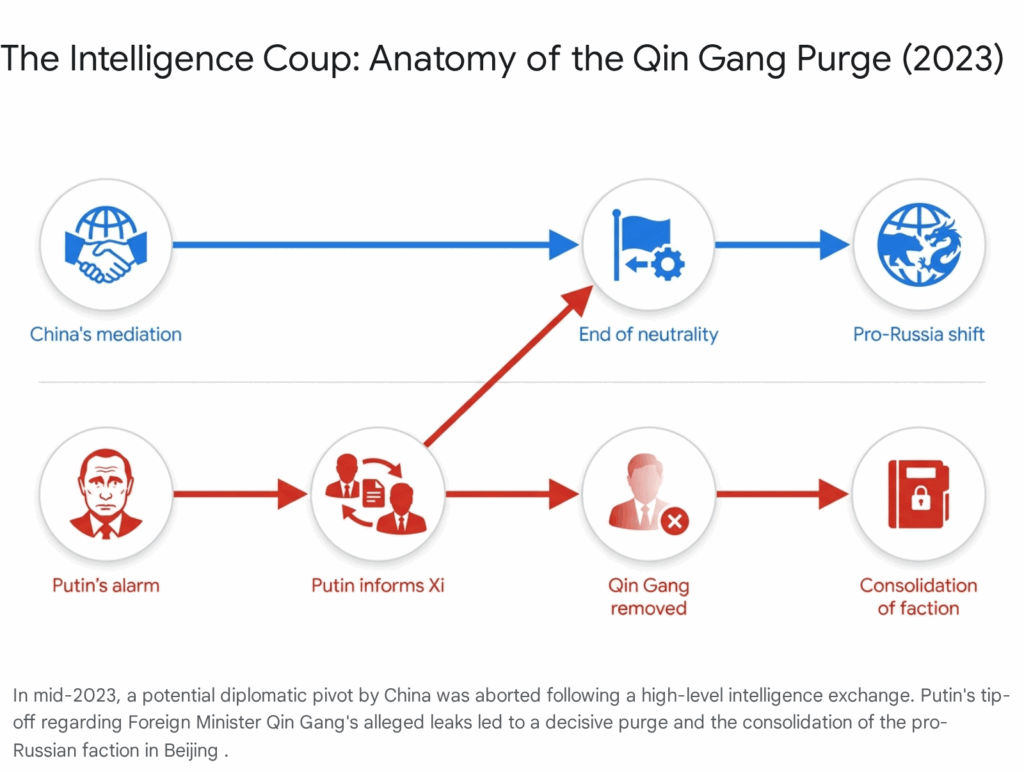

2.3 The Qin Gang Incident: A Case Study in Transactional Trust

A defining moment in the personal trust dynamic occurred in 2023, highlighting the shadowy intelligence-sharing aspect of their bond. This incident underscores that their “friendship” is maintained through high-stakes exchanges of regime-security information.

- The Leak: According to intelligence reports, Putin personally tipped off Xi Jinping that Xi’s protégé and Foreign Minister, Qin Gang, had allegedly leaked secrets to the United States. This intelligence likely came from Russian penetration of Western communication networks or human sources.13

- The Purge: Following this tip-off, Qin Gang was swiftly removed and vanished from public view. This incident demonstrates that Putin possesses deep intelligence assets capable of monitoring the periphery of the CCP’s inner circle and is willing to share this “kompromat” to buy Xi’s trust. It was a strategic move to eliminate pro-Western factions within the Chinese Foreign Ministry that were advocating for a more neutral stance on Ukraine.13

- Strategic Impact: This move likely saved the “no limits” partnership at a fragile moment when Beijing was flirting with genuine neutrality in the Ukraine war. By exposing a “traitor,” Putin solidified the position of the pro-Russian faction in Beijing, led by figures who view the U.S. as the primary antagonist.

Section III: The Mechanics of the Axis: Military and Intelligence Integration

While the West often fears a unified Sino-Russian military bloc, analysis reveals a relationship that is broad but shallow. It is characterized by high-level political signaling and technical interdependence but lacks the command-and-control interoperability of an alliance like NATO. The two militaries are not training to fight together so much as they are training to fight alongside each other against a common foe.

3.1 Military Cooperation: Drills without Integration

China and Russia have significantly increased the frequency and complexity of their joint military exercises, conducting naval drills in the Pacific and joint bomber patrols over the Sea of Japan and the East China Sea.16

- Political Signaling: The primary function of these exercises is diplomatic—signaling to the U.S. and its allies (Japan, South Korea) that the two powers can project force jointly. They serve as a deterrent, demonstrating that a war with one could potentially draw in the other.18

- Interoperability Limits: Despite years of joint drills, true interoperability remains elusive.

- Language Barriers: Tactical communication is hampered by significant language differences. Unlike NATO’s standardized English, Russian and Chinese troops struggle to communicate effectively in real-time combat scenarios. Joint commands often rely on translators, introducing latency that would be fatal in modern kinetic warfare.19

- Command Structures: There is no integrated command structure. Exercises are often scripted events rather than dynamic war-games that test joint responses to unplanned contingencies. The two militaries maintain distinct operational cultures and planning processes.19

- Trust Deficit: Both militaries are secretive. Russia has historically been wary of sharing its most sensitive electronic warfare and submarine protocols, fearing Chinese reverse-engineering. This limits the depth of their integration to “de-confliction” and basic coordination rather than full fusion.18

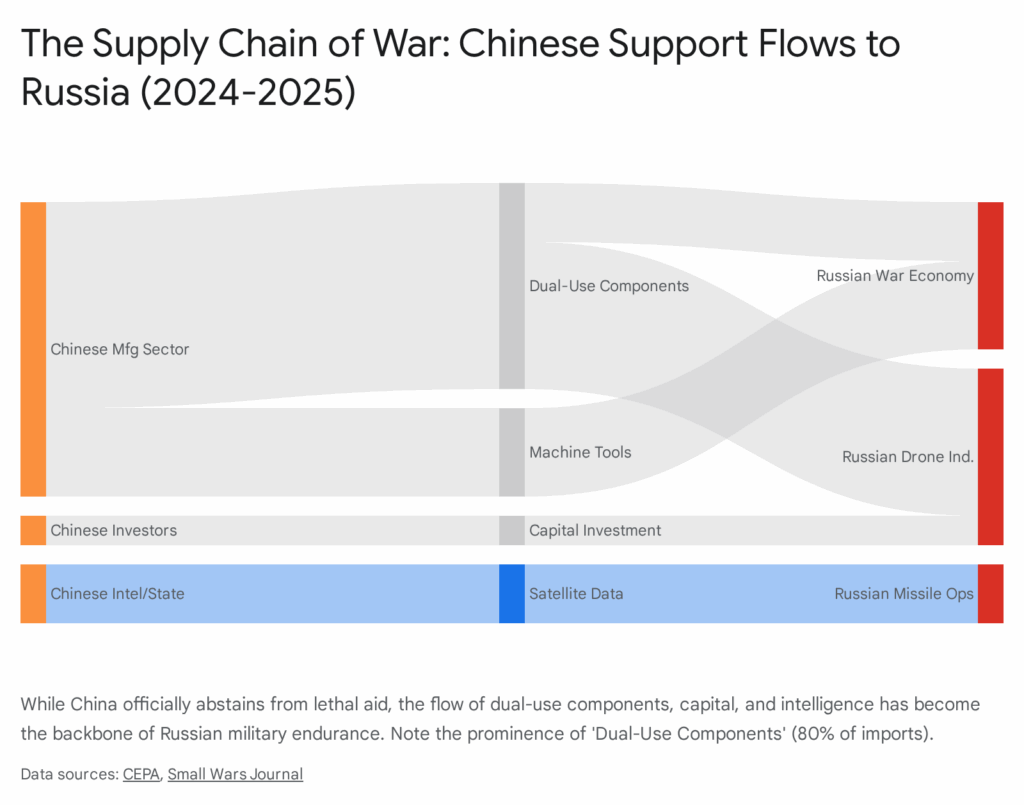

3.2 The Defense-Industrial Symbiosis

The most substantive aspect of their military relationship is industrial. The flow of technology has reversed: historically, Russia supplied China with finished weapon systems (Su-27s, S-300s). Now, China supplies Russia with the components necessary to sustain its war machine, creating a dependency that fundamentally alters the strategic balance.

- The Drone Nexus: Chinese entities are deeply embedded in Russia’s drone warfare capabilities. Russian drone manufacturers like Rustakt have received direct investment from Chinese business magnates such as Wang Dinghua. Leaked data indicates that up to 80% of foreign components in Russian military technology are now of Chinese origin.21

- Dual-Use Goods: China supplies Russia with machine tools, turbojet engines (e.g., for the Geran-3), and optics. This support is crucial for Russia to bypass Western sanctions and maintain high-intensity operations in Ukraine. Without this “non-lethal” aid, Russia’s military-industrial complex would likely face severe bottlenecks.21

- Space and Intelligence: Cooperation has extended to the space domain, a sensitive area previously guarded by Moscow. Reports indicate China provides Russia with satellite imagery (via the Yaogan constellation) to aid in targeting for missile strikes in Ukraine.21 This “intelligence-as-a-service” model allows China to support Russia’s war effort without crossing the red line of providing lethal aid directly from state stocks, maintaining a veil of plausible deniability.

Section IV: Economic and Technological Asymmetry

The economic dimension of the relationship is characterized by the rapid “Yuanization” of the Russian economy and the encroachment of Chinese digital infrastructure. This is not a merger of equals; it is the absorption of a resource colony by an industrial superpower. The data presents a picture of Russia moving from a diversified trading partner of Europe to a captive market for China.

4.1 Trade and Energy: The Buyer’s Market

Since the invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent Western sanctions, Russia’s trade has pivoted violently toward China.

- Trade Volume: Bilateral trade reached $240 billion in 2023, with China replacing the EU as Russia’s primary partner. China now accounts for roughly 30-38% of Russia’s exports and 35-40% of its imports. This is a staggering shift from the pre-war era, where the EU accounted for nearly half of Russia’s exports.23

- The Power of Siberia 2 Standoff: The negotiations over the Power of Siberia 2 gas pipeline exemplify the power imbalance. Despite Russia’s desperation to replace the lost European market, Beijing has stalled the deal.

- Price Dispute: China is demanding domestic Russian gas prices, effectively seeking subsidized energy. Beijing knows Russia has few other options and is leveraging this monopsony power.

- Strategic Hesitation: Beijing is wary of over-dependence on a single supplier. The pipeline delay is a calculated message: Russia needs China more than China needs Russia. Negotiations are bogged down in discussions over price and flexibility, with Beijing showing no urgency to conclude the deal.25

4.2 Yuanization of the Russian Financial System

The sanctions on Russia’s central bank and exclusion from SWIFT have forced the Kremlin to adopt the Chinese Yuan (RMB) as its primary reserve and settlement currency. This phenomenon, termed “Yuanization,” represents a significant loss of monetary sovereignty for Moscow.

Table 1: The Yuanization of Russian Trade Settlements

| Metric | Pre-War (Jan 2022) | Mid-War (2024-2025) | Implication |

| Export Settlement Share (CNY) | 0.4% | >34% | High dependency on Beijing’s monetary policy. |

| MOEX Trading Volume (RUB/CNY) | ~1% | ~50% (Peak) | The Yuan replaced the Dollar as the benchmark. |

| “Unfriendly” Currency Share | >85% | <20% | Successful decoupling from the West, but at the cost of diversification. |

| Financial Liquidity | High (Global Access) | Constrained (Yuan Shortages) | Periodic liquidity crunches when Chinese banks restrict flow. |

Data synthesized from Central Bank of Russia and USCC reports.28

- Currency Composition: As shown in Table 1, the share of export settlements in Yuan exploded from virtually zero to over a third of all trade. Trading of the Ruble-Yuan pair on the Moscow Exchange (MOEX) dominated the market before sanctions forced trading over-the-counter.28

- Risks: This “Yuanization” subordinates Russia’s monetary policy to Beijing. During liquidity stress events, the cost of borrowing Yuan in Russia spikes, and the Russian Central Bank cannot print Yuan to alleviate the crunch. Russia has effectively outsourced its financial stability to the People’s Bank of China.28

4.3 The Digital Panopticon: Tech Stack Integration

A less visible but highly strategic trend is the integration of Russian and Chinese surveillance states. This “technological authoritarianism” creates a shared digital ecosystem that is difficult to disentangle.

- SORM vs. Digital Silk Road: Russia’s SORM (System for Operative Investigative Activities) relies on deep packet inspection (DPI) hardware to monitor communications. Historically, this was supported by domestic or Western tech. Now, Chinese firms like Huawei are building the data centers and cloud infrastructure in Russia and its sphere of influence (Central Asia).

- Surveillance Exports: In Central Asia, a hybrid model is emerging where Russian legal frameworks (SORM requirements) are implemented using Chinese hardware (Safe City cameras, facial recognition). This creates a “tech stack” that binds the region to both Moscow and Beijing, though the hardware dependence favors China in the long run. The integration of Chinese “Golden Shield” style censorship tools with Russian SORM protocols creates a robust authoritarian control grid.29

- Tech Transfer: China is Russia’s only source for high-tech semiconductors and 5G equipment, giving Beijing a potential “kill switch” over Russia’s future modernization. Russia is struggling to produce its own microchips and is increasingly reliant on smuggled or gray-market Chinese imports.23

Section V: Geopolitical Friction: Central Asia and the Arctic

While the leaders project unity, their geopolitical interests collide in the “seams” of their empires. Central Asia and the Arctic are the primary theaters where the “No Limits” partnership meets the hard reality of competing national interests.

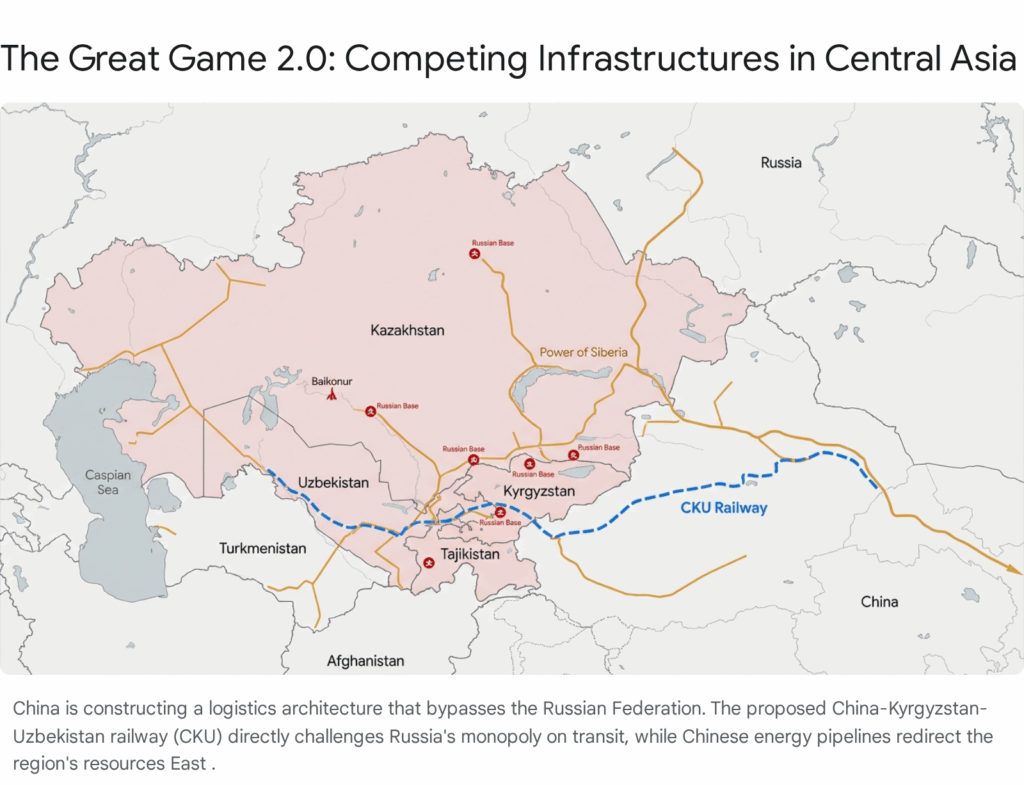

5.1 Central Asia: The Silent Struggle

Central Asia is the traditional sphere of Russian influence, often referred to as Russia’s “soft underbelly.” However, China is rapidly usurping this role through economic gravity, challenging the tacit agreement where Russia provided security and China provided economic investment.

- Infrastructure Bypass: China is pushing the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan (CKU) railway, a project that bypasses Russian territory entirely. This undermines Russia’s control over transit routes between Asia and Europe and reduces the leverage Moscow holds over the Central Asian republics.30

- Security Encroachment: Historically, the division of labor was “Russian guns, Chinese money.” This is eroding. China is increasing its security footprint through the sale of surveillance tech and bilateral military drills with Central Asian states, subtly challenging Russia’s role as the region’s sole security guarantor.30

- Diplomatic Erosion: Russia’s inability to project soft power—due to its war and diminished resources—has forced Central Asian leaders to pursue “multi-vector” foreign policies. They are increasingly looking to Beijing, and even the West, to balance against a revanchist Moscow. The EU’s Global Gateway program is also finding receptive partners in the region, further diluting Russia’s monopoly.30

5.2 The Arctic: A Wary Welcome

Russia has historically been protective of the Arctic, viewing the Northern Sea Route (NSR) as an internal waterway and a strategic bastion for its nuclear deterrent. However, isolation and financial necessity have forced a pragmatic, albeit reluctant, opening to China.

- The Polar Silk Road: China views itself as a “near-Arctic state” and seeks access to the NSR for shipping to reduce travel time to Europe. Russia, starved of capital for icebreakers and port infrastructure, has reluctantly accepted Chinese investment. This acceptance is driven by necessity, not strategic alignment.32

- Sovereignty Friction: Tensions remain palpable. Russia has previously blocked Chinese research vessels and remains suspicious of China’s long-term intentions in the region. Cooperation is transactional: Russia allows access because it has no choice, but it continues to view China’s presence as a potential encroachment on its sovereignty. The Kremlin is careful to maintain legal control over the route, even as it invites Chinese capital.33

Section VI: Durability Assessment and Future Scenarios

Will the alliance last? The consensus among intelligence and foreign affairs analysts is that the partnership is durable in the medium term (5-10 years) but structurally unsound in the long term. It is an axis of convenience that will likely persist as long as the current leaderships remain in place and the external threat environment remains constant.

6.1 The Glue: Shared Adversaries

The single strongest bonding agent is the United States. As long as both regimes view Washington as an existential threat actively seeking their overthrow (via “color revolutions” or “peaceful evolution”), they will suppress their bilateral frictions.

- Mutual Buffer: China needs a friendly Russia to secure its northern border and energy supply in the event of a naval blockade in the Taiwan Strait. Russia needs China as an economic lifeline and diplomatic shield against Western isolation. This mutual vulnerability creates a powerful incentive to maintain the partnership despite internal disagreements.35

- Triangle Diplomacy: Chinese strategic thought still relies on the “strategic triangle” concept (US-China-Russia). Beijing believes that maintaining good relations with Moscow is essential to prevent the US from focusing all its resources on containment of China. As long as the US is seen as the primary antagonist, the Sino-Russian bond will hold.37

6.2 The Fracture Points

However, several stressors could fracture the axis over the longer term:

- Post-Putin Succession: The alliance is heavily personalized around the Putin-Xi connection. If Putin were to die or be incapacitated, the succession crisis could lead to instability. A nationalist successor might resent Chinese dominance, or a pragmatist might seek rapprochement with the West to rebuild the economy. China fears a chaotic Russia or a pro-Western Russia more than anything, and may intervene in a succession crisis to ensure a favorable outcome.38

- Economic Cannibalization: As Chinese companies aggressively capture Russian market share (autos, electronics), Russian domestic industry may eventually push back against “colonization.” The resentment of the Russian elite, who are watching their country’s sovereignty erode, could eventually boil over into political opposition to the China tilt.12

- Military Escalation: If China were to invade Taiwan, it would expect Russian support. Russia’s ability or willingness to open a second front or provide material aid while bogged down in Ukraine is questionable. Conversely, if Russia uses a tactical nuclear weapon in Ukraine, China would likely distance itself immediately to preserve its global standing and avoid total economic warfare with the West. China has consistently signaled its opposition to nuclear escalation.40

6.3 Endgame Scenarios (2025-2030)

| Scenario | Probability | Description | Implications for the West |

| The Vasal State | High | The status quo continues. Russia becomes an economic resource appendage of China. Putin accepts junior status in exchange for regime survival and protection from Western pressure. | Russia remains a rogue actor fueled by Chinese money. The West faces a two-front challenge where Moscow acts as a spoiler for Beijing. |

| The Silent Divorce | Medium | China pivots to repair relations with the EU/US to salvage its own slowing economy. Support for Russia becomes purely symbolic. Friction in Central Asia intensifies. | Russia is isolated and may become more desperate/volatile. Opportunities for the West to peel Beijing away from Moscow through diplomatic incentives. |

| The Military Pact | Low | Formal mutual defense treaty signed. Full integration of command structures. Likely only triggered by a direct US war with one party. | Global bifurcation into two rigid blocs. High risk of World War III. This is unlikely due to China’s desire to avoid “entangling alliances.” |

Conclusion

The Putin-Xi relationship is not a marriage of love, nor merely one of convenience—it is a “marriage of necessity.” They are two authoritarian survivors huddled back-to-back against a perceived Western siege.

Vladimir Putin, the reactive tactician, has mortgaged Russia’s future to Beijing to secure his present survival. He has traded strategic autonomy for tactical endurance. Xi Jinping, the strategic planner, has accepted the burden of a declining, volatile Russia because it serves as a necessary geopolitical distraction for his primary rival, the United States. He views Russia as a flawed but essential instrument in his grand strategy of national rejuvenation.

While they view each other with a mix of camaraderie and deep, historical suspicion, their fates are now inextricably linked. The alliance will likely endure as long as Putin remains in power and the United States remains the hegemon. However, the seeds of its dissolution—arrogance, asymmetry, and historical grievance—are already sown in the soil of their cooperation. For Western policymakers, the strategy should not be to wait for a breakup, but to exploit the friction points in Central Asia and the Arctic, and to prepare for the inevitable instability that will arise when the junior partner in this axis eventually chafes against its chains.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- Comparative Analysis of Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping: Pathways to …, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.faf.ae/home/2025/3/1/comparative-analysis-of-vladimir-putin-and-xi-jinping-pathways-to-power-and-leadership-dynamics

- Vladimir Putin’s Leadership Trait Analysis in Russia’s Responses towards China’s One Belt One Road (OBOR) Initiative – SciTePress, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.scitepress.org/Papers/2018/102744/102744.pdf

- Putin presents China’s Xi with giant box of birthday ice creams – The Times of Israel, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.timesofisrael.com/putin-presents-chinas-xi-with-giant-box-of-birthday-ice-creams/

- (PDF) STRATEGIC DISCOURSES: A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF XI JINPING’S AND VLADIMIR PUTIN’S SPEECHES ON CENTRAL ASIA – ResearchGate, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/393428908_STRATEGIC_DISCOURSES_A_CONTENT_ANALYSIS_OF_XI_JINPING’S_AND_VLADIMIR_PUTIN’S_SPEECHES_ON_CENTRAL_ASIA

- Why do Chinese people sympathise with Russia? – ThinkChina.sg, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.thinkchina.sg/politics/why-do-chinese-people-sympathise-russia

- China and Russia: Exploring Ties Between Two Authoritarian Powers | Council on Foreign Relations, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounders/china-russia-relationship-xi-putin-taiwan-ukraine

- Putin and Xi: Ice Cream Buddies and Tandem Strongmen – PONARS Eurasia, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.ponarseurasia.org/putin-and-xi-ice-cream-buddies-and-tandem-strongmen/

- Vladimir Putin wished Xi Jinping a happy birthday – President of Russia, accessed January 30, 2026, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/60757

- The Xi-Putin dynamic: Belief differences and the future of Sino …, accessed January 30, 2026, https://blogs.griffith.edu.au/asiainsights/the-xi-putin-dynamic-belief-differences-and-the-future-of-sino-russian-relations/

- Explainer: Where Moscow and Beijing do not see eye-to-eye – BBC Monitoring, accessed January 30, 2026, https://monitoring.bbc.co.uk/product/c204o35y

- Anti-Chinese sentiment – Wikipedia, accessed January 30, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-Chinese_sentiment

- Racism Against Chinese in Russia | PDF | Xenophobia … – Scribd, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.scribd.com/document/875574004/Racism-Against-Chinese-in-Russia

- China-Russia alignment and military cooperation is bad news, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/china-russia-alignment-cooperation-ukraine-war-military-supplies-putin-xi-jinpin/

- Turning point? Putin, Xi, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine – Lowy Institute, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/turning-point-putin-xi-russian-invasion-ukraine

- Putin’s arrogance hurting Russia’s interests, growing China ties a strategic risk: Polish Deputy PM at JLF – The Hans India, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.thehansindia.com/news/international/putins-arrogance-hurting-russias-interests-growing-china-ties-a-strategic-risk-polish-deputy-pm-at-jlf-1040263

- Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2025 – DoD, accessed January 30, 2026, https://media.defense.gov/2025/Dec/23/2003849070/-1/-1/1/ANNUAL-REPORT-TO-CONGRESS-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA-2025.PDF

- China and Russia challenge the Arctic order | DIIS, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.diis.dk/en/research/china-and-russia-challenge-the-arctic-order

- China-Russia Military-to-Military Relations: Moving Toward a Higher Level of Cooperation – U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/China-Russia%20Mil-Mil%20Relations%20Moving%20Toward%20Higher%20Level%20of%20Cooperation.pdf

- An Emerging Strategic Partnership: Trends in Russia-China Military Cooperation, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.marshallcenter.org/en/publications/security-insights/emerging-strategic-partnership-trends-russia-china-military-cooperation-0

- Russia and China Military Cooperation: Just Short of an Alliance …, accessed January 30, 2026, https://cepa.org/comprehensive-reports/partnership-short-of-alliance-military-cooperation-between-russia-and-china/

- The US Must Beware the Deepening China-Russia Axis – CEPA, accessed January 30, 2026, https://cepa.org/article/the-us-must-beware-the-deepening-china-russia-axis/

- The Limits of the China–Russia Strategic Partnership in Military Space Cooperation, accessed January 30, 2026, https://smallwarsjournal.com/2026/01/30/the-limits-of-space-cooperation/

- Russia is shifting its foreign trade massively towards China (news article), accessed January 30, 2026, https://wiiw.ac.at/russia-is-shifting-its-foreign-trade-massively-towards-china-n-695.html

- China-Russia Dashboard: Facts and figures on a special relationship | Merics, accessed January 30, 2026, https://merics.org/en/china-russia-dashboard-facts-and-figures-special-relationship

- Why Can’t Russia and China Agree on the Power of Siberia 2 Gas Pipeline?, accessed January 30, 2026, https://carnegieendowment.org/russia-eurasia/politika/2025/09/russia-china-gas-deals

- Russia, China Slow to Progress Power of Siberia 2 Natural Gas Negotiations, accessed January 30, 2026, https://naturalgasintel.com/news/russia-china-slow-to-progress-power-of-siberia-2-natural-gas-negotiations/

- Why China and Russia are unlikely to move the Power of Siberia-2 pipeline forward, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/why-china-and-russia-are-unlikely-to-move-the-power-of-siberia-2-pipeline-forward/

- Elina Ribakova | US-China Economic and Security Review Commission | February 20, 2025 Export Controls and Technology Transfer: Lessons from Russia, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2025-02/Elina_Ribakova_Testimony.pdf

- Russia and China in Central Asia’s Technology Stack – German …, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.gmfus.org/sites/default/files/2025-06/Russia%20and%20China%20in%20Central%20Asia%E2%80%99s%20Technology%20Stack.pdf

- Russia, China, and the Race to Rebuild the Silk Road, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.youngausint.org.au/post/russia-china-and-the-race-to-rebuild-the-silk-road

- Sino-Russian Relations in Central Asia – CEPA, accessed January 30, 2026, https://cepa.org/commentary/sino-russian-relations-in-central-asia/

- A Pragmatic Approach to Conceptual Divergences in Russia-China Relations: the Case of the Northern Sea Route | The Arctic Institute – Center for Circumpolar Security Studies, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/pragmatic-approach-conceptual-divergences-russia-china-relations-case-northern-sea-route/

- Friction Points in the Sino-Russian Arctic Partnership – NDU Press, accessed January 30, 2026, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Joint-Force-Quarterly/Joint-Force-Quarterly-111/Article/Article/3571034/friction-points-in-the-sino-russian-arctic-partnership/

- Sino-Russian Cooperation in the Arctic – CEPA, accessed January 30, 2026, https://cepa.org/comprehensive-reports/sino-russian-cooperation-in-the-arctic/

- The limits of authoritarian compatibility: Xi’s China and Putin’s Russia – Brookings Institution, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/FP_20200615_the_limits_of_authoritarian_compatibility_xis_china_and_putins_russia.pdf

- Three years of war in Ukraine: the Chinese-Russian alliance passes the test – OSW, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-commentary/2025-01-20/three-years-war-ukraine-chinese-russian-alliance-passes-test

- Country Report: China (June 2025) – The Asan Forum, accessed January 30, 2026, https://theasanforum.org/country-report-china-june-2025/

- Future Scenarios of Russia-China Relations: Not Great, Not Terrible? – SCEEUS, accessed January 30, 2026, https://sceeus.se/en/publications/future-scenarios-of-russia-china-relations-not-great-not-terrible/

- Scenarios | After Putin, the deluge? – Clingendael, accessed January 30, 2026, https://www.clingendael.org/pub/2023/after-putin-the-deluge/scenarios/

- China-Russia alignment: a threat to Europe’s security | Merics, accessed January 30, 2026, https://merics.org/en/report/china-russia-alignment-threat-europes-security