| This is a time-sensitive special report and is based on information available as of January 5, 2026. Due to the situation being very dynamic the following report should be used to obtain a perspective but not viewed as an absolute. |

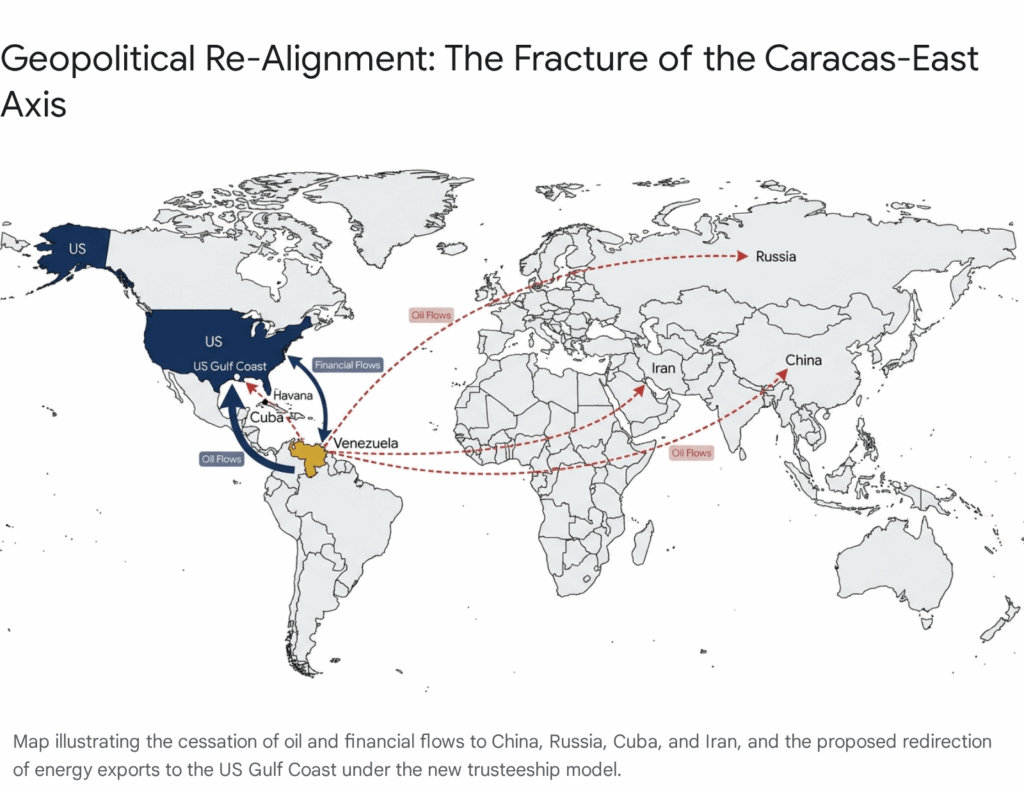

The military intervention in Venezuela, designated operationally as “Operation Absolute Resolve,” marks a definitive inflection point in the geopolitical history of the Western Hemisphere. The seizure of President Nicolás Maduro and the subsequent assertion of a United States-led “trusteeship” over the nation’s energy infrastructure represents more than a regime change operation; it is a fundamental restructuring of the global energy architecture. By placing the world’s largest proven oil reserves under direct US administration, Washington has effectively removed a critical node from the geopolitical “Axis of Resistance”—comprising China, Russia, and Iran—and reoriented Venezuela’s economic gravity back toward the North American energy orbit.

This report, authored by a collaborative team of national security, foreign affairs, and energy market analysts, provides an exhaustive assessment of the cascading impacts of this intervention. Our analysis suggests that the immediate objective extends beyond the removal of a hostile governing clique. The operation serves as a forceful implementation of “Resource Realism,” a doctrine that prioritizes the physical control of strategic assets over traditional diplomatic engagement. The administration’s explicit goal to “reimburse” US intervention costs through Venezuelan oil revenue 1 creates a legal and financial precedent that subordinates sovereign debt obligations to the operational imperatives of the occupying power.

The most acute and immediate impact will be the existential crisis facing Cuba. With Venezuela previously supplying between 40% and 60% of the island’s energy needs through favorable barter arrangements, the abrupt cessation of these flows threatens to precipitate a total collapse of the Cuban electric grid within the current calendar year. This development raises the specter of a humanitarian catastrophe and a mass migration event of a magnitude not seen since the Mariel boatlift. Simultaneously, China faces a “sunk cost” dilemma of historic proportions, with an estimated $10–20 billion in oil-backed loans at risk of nullification under the “Odious Debt” doctrine.

Contrary to the optimistic political rhetoric suggesting a rapid recovery, our forensic analysis of the Venezuelan oil sector indicates a profound “Reality Gap.” The infrastructure of Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) suffers from catastrophic degradation. While political leadership suggests a recovery timeline of 18 months, industry consensus points to a requirement of nearly $100 billion in capital investment over a decade to restore production to pre-Chávez levels. Consequently, the “Venezuela Premium” in global oil markets will shift from a risk of supply disruption to a “Reconstruction Lag,” where the anticipated flood of new supply is delayed by technical and legal realities.

This report maps the chain of impacts across the globe, analyzes the legal mechanisms of the takeover, and forecasts the reshaping of the Western Hemisphere’s energy markets, including the displacement of Canadian crude and the nullification of Russian strategic depth in the region.

1. The Strategic Calculus of Operation Absolute Resolve

The transition from a decade-long policy of sanctions and diplomatic isolation to direct kinetic intervention and asset seizure represents a paradigm shift in United States foreign policy. While the operation was framed publicly as a law enforcement action to apprehend indicted “narco-terrorists,” the strategic underpinnings reveal a calculated effort to dismantle the economic lifelines of US adversaries in the Western Hemisphere.

1.1 The Doctrine of “Reimbursement” and Trusteeship

Central to the post-intervention strategy is the concept of “reimbursement,” articulated by President Trump immediately following the operation. The declaration that the US will “run” Venezuela until stability is achieved, and that American oil companies will be “reimbursed” for their investments and the nation’s reconstruction costs through oil revenue 1, introduces a de facto trusteeship model. This approach is distinct from nation-building efforts in Iraq or Afghanistan; it is explicitly transactional, treating the Venezuelan state’s primary asset as collateral for the intervention itself.

The “reimbursement” mechanism implies a rigid hierarchy of revenue distribution that fundamentally alters the sovereign risk profile of the country. Revenue generated from the rehabilitation of fields in the Orinoco Belt or the Lake Maracaibo basin will likely be ring-fenced within US-controlled escrow accounts. The prioritization of claims is expected to follow a specific order:

- Operational Expenditures (OpEx): Immediate payments to US operators (e.g., Chevron, Halliburton) to maintain flow assurance.

- Capital Recovery (CapEx): Repayment of new infrastructure investments required to resuscitate the grid and pipelines.

- Intervention Costs: Direct reimbursement to the US Treasury for the logistical and military costs of Operation Absolute Resolve.

- Sovereign Debt and State Budget: Only after these primary tranches are satisfied would residual revenue flow to the Venezuelan central bank or legacy creditors.

This structure explicitly subordinates the claims of existing creditors—most notably China and Russia—and creates a legal and financial firewall around Venezuelan production. It effectively treats PDVSA not as a national oil company (NOC) in the traditional sense, but as a distressed asset under administration.3

1.2 Intent Analysis: Deliberate Choking vs. Secondary Effect

A critical question posed by observers is whether the choking of oil flows—and the consequent starvation of hard currency to the Maduro regime—was a deliberate goal of the US government or a secondary outcome of the “narco-terrorism” operation. Our analysis of the timeline and enforcement mechanisms confirms that the economic strangulation was a deliberate, primary strategic objective.

The evidence for this intent is found in the escalation sequence preceding the kinetic operation. The US administration systematically tightened the blockade on the “shadow fleet”—the network of ghost tankers used by PDVSA to evade sanctions.4 By targeting specific vessels like the Nord Star and Lunar Tide, and sanctioning their registered owners just days before the operation 6, the US effectively severed the financial capillaries that kept the regime solvent.

Furthermore, the immediate post-operation blockade of tankers bound for Cuba and China 7 indicates a pre-planned effort to weaponize energy dominance. The goal was twofold: to degrade the regime’s ability to pay its security services in the final hours, and to deny US adversaries (China and Iran) a secure source of energy and revenue. The operation fulfills the administration’s stated geopolitical ambition that “American dominance in the western hemisphere will never be questioned again”.8 The dismantling of the oil-for-loans infrastructure was not collateral damage; it was the target.

1.3 The “Putinization” of US Foreign Policy?

International observers have noted a convergence in style between the US action and the spheres-of-influence strategies typically associated with Russia. Commentators have termed this the “Putinization of US foreign policy,” characterized by the use of overwhelming force to determine political outcomes in the “near abroad”.9 However, unlike the Russian approach in Ukraine, the US strategy in Venezuela relies heavily on the subsequent mobilization of private capital (US oil majors) to consolidate the gain, blending state military power with corporate industrial capacity.

2. The Asset: Forensic Audit of the Venezuelan Oil Industry

The “prize” secured by US forces—the world’s largest proven oil reserves, estimated at over 300 billion barrels—is, in immediate practical terms, a deeply distressed asset. There is a profound disconnect between the political rhetoric of immediate wealth generation and the industrial reality on the ground.

2.1 The Infrastructure Deficit

Decades of mismanagement, the “brain drain” following the 2002–2003 PDVSA strikes, and stringent sanctions have left the industry in a state of collapse. Production has fallen from a peak of approximately 3.5 million barrels per day (bpd) in the late 1990s to roughly 1 million bpd at the time of the intervention.10

Upstream Decay: The unique geology of Venezuela’s Orinoco Belt requires constant diligence. The extra-heavy crude produced there must be diluted or upgraded immediately to be transportable. Due to the lack of diluents (previously imported from Iran or the US) and the failure of upgraders, thousands of wells have been shut in. Once shut, these wells often suffer from reservoir damage that makes reactivation economically unviable; they do not simply turn back on.12

Downstream Paralysis: The refining sector is in equally dire straits. The Paraguaná Refining Center, once one of the largest in the world with a capacity of 940,000 bpd, is operating at roughly 10% capacity.13 Critical units for producing gasoline and diesel are offline due to a lack of spare parts and catalytic agents. Pipelines crossing Lake Maracaibo are riddled with leaks, creating an ecological disaster that complicates immediate reactivation.14

2.2 The Recovery Timeline and Cost: The Reality Gap

President Trump’s suggestion that oil production could ramp up significantly within “18 months” 15 stands in stark contrast to industry consensus.

- Political Forecast: The administration envisions a rapid turnaround where US efficiency quickly restores output, funding the intervention and stabilizing the global market.

- Industry Reality: Experts and analysts, including those from Rice University and Rystad Energy, estimate that restoring production to the 3–4 million bpd level will require between $80 billion and $100 billion in capital investment over a period of 7 to 10 years.11

This “Reality Gap” is substantial. Even under the most optimistic scenarios, where US firms assume immediate operational control, output is unlikely to exceed 1.5 million bpd within the first 2–3 years.17 The initial phase of “recovery” will likely consist of stabilizing current decline rates and repairing critical safety infrastructure rather than a boom in new exports.

2.3 The Role of US Majors

While the US President claims American oil companies are “prepared” to enter, the corporate reality is one of extreme caution.

- Chevron: As the only US major currently operating in Venezuela (under previous OFAC waivers), Chevron is the linchpin of the immediate stabilization plan. They currently ship approximately 150,000 bpd to the US 18 and have the most up-to-date knowledge of the reservoir conditions.

- ExxonMobil & ConocoPhillips: These firms were expropriated by Hugo Chávez and hold outstanding arbitration awards worth billions ($1.6 billion and $12 billion+, respectively).19 Their return is contingent not just on security, but on the settlement of these past debts. It is highly unlikely they will commit new shareholder capital without a “sovereign guarantee” or a mechanism that prioritizes their debt recovery from new production revenues.20

3. The Primary Casualty: Cuba’s Existential Crisis

The most immediate, severe, and potentially destabilizing impact of the US takeover of Venezuelan oil will be felt not in Caracas, but in Havana. For two decades, Venezuela has been the economic guarantor of the Cuban Revolution, a relationship that is now effectively terminated.

3.1 Energy Dependence and the mechanism of Collapse

Cuba relies on Venezuela for between 40% and 60% of its total oil consumption. This oil was not purchased on the open market but provided through favorable cooperation agreements, often involving the exchange of Cuban medical personnel, intelligence agents, and security advisors for crude oil and refined products.21

The mechanics of this trade have already been disrupted. In the months leading up to the intervention, Venezuelan exports to Cuba plummeted from ~80,000 bpd to near zero due to the US blockade and the seizure of tankers like the Liza and Sandino.22 With the US military now controlling the export terminals at Jose and Puerto Miranda, the possibility of resuming these “solidarity shipments” is non-existent.

Grid Failure: The Cuban electric grid is antiquated, fragile, and almost entirely dependent on floating Turkish power ships and obsolete Soviet-era thermoelectric plants that burn Venezuelan heavy fuel oil. The loss of this specific grade of fuel is catastrophic. Without it, the grid cannot function. Reports indicate that blackouts are already extending to 12–18 hours a day.23 A total collapse of the National Electric System (SEN) is projected within months.

3.2 Regime Stability and Mass Migration

The US administration explicitly views the collapse of the Cuban regime as a likely corollary to the Venezuelan operation. President Trump has stated, “I think it’s just going to fall”.24 The logic is cold but sound: without Venezuelan oil, Havana lacks the hard currency to purchase fuel on the open market, especially given its own economic crisis and US sanctions.

Migration Crisis: The inevitable result of a permanent blackout and economic paralysis is a mass migration event. We forecast a surge in maritime migration toward Florida in mid-to-late 2026 that could dwarf the 1980 Mariel boatlift and the 1994 rafter crisis. This poses a significant domestic political challenge for the US administration, which must balance its pressure campaign with the optics of a humanitarian disaster on its shores.

Regional Isolation: Mexico, which briefly provided emergency fuel shipments in late 2025, has signaled it cannot sustain Cuba. Faced with its own production constraints and the risk of antagonizing a belligerent US administration, Mexico has reduced its aid, leaving Cuba with no alternative lifeline.22

4. The Great Power Pivot: China and the Sunk Cost Fallacy

For the People’s Republic of China, the US intervention represents a massive financial loss and a significant strategic setback. Venezuela was one of the largest recipients of Chinese development finance in the world, a relationship built on the “loans-for-oil” model.

4.1 The Financial Blow: $20 Billion at Risk

China is Venezuela’s largest creditor, with outstanding loans estimated between $10 billion and $20 billion.25 These loans were structured to be repaid in oil shipments, a mechanism that functioned reasonably well until the intensification of sanctions.

Under the new US trusteeship, these debts are in jeopardy. The US strategy likely involves classifying these loans not as sovereign obligations of the Venezuelan state, but as distinct liabilities incurred by the Maduro regime to sustain its grip on power. This classification paves the way for the invocation of the “Odious Debt” doctrine (discussed further in Section 9), which would legally subordinate or nullify China’s claims in favor of US reconstruction costs and pre-Chávez creditors.26

4.2 Asset Vulnerability and Supply Chains

Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs), specifically China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and Sinopec, hold significant minority stakes in joint ventures such as Petrosinovensa.27

- Operational Loss: While CNPC technically owns shares in these fields, their ability to lift oil or influence operations is now zero. The US occupation forces control the physical infrastructure. It is expected that these JVs will be placed under “administrative review,” effectively freezing Chinese equity.

- Supply Diversion: Approximately 470,000 bpd of Venezuelan crude flowed to China in 2025, largely to independent “teapot” refiners in Shandong province who thrived on the discounted heavy crude.27 This flow has been severed. China must now replace this volume, likely by increasing imports from Iran or Russia. This tightens the “shadow market” and potentially raises costs for Chinese independent refiners, though the global impact is mitigated by weak demand growth in China.

4.3 Diplomatic Stance

Beijing has publicly condemned the US action, emphasizing the inviolability of sovereignty. However, China’s response is constrained by its own economic slowdown and the desire to avoid a direct military confrontation in the Western Hemisphere. China’s strategy will likely focus on “damage control”—using international courts and diplomatic leverage to try and salvage some financial value from its investments, though expectations of a total write-down are high.26

5. The Russian Retreat and Iranian Disconnect

The operation effectively dismantles the “Axis of Resistance” presence in Latin America, dealing a blow to Russian prestige and Iranian logistical networks.

5.1 Russia: Geopolitical Eviction

For Moscow, Venezuela was a strategic beachhead—a way to project power into the US “near abroad” in reciprocity for US presence in Eastern Europe.

- Roszarubezhneft: This state entity was created specifically to take over Rosneft’s Venezuelan assets in 2020 to shield the parent company from sanctions.30 These assets, including stakes in the Petromonagas upgrader, are now under US control. The physical loss of these fields represents a write-off of billions of dollars in investment.12

- Strategic Defeat: The intervention serves as a demonstration of Russia’s inability to protect its distant allies. The “Putinization” of US policy essentially beats Russia at its own game, using overwhelming force to secure a sphere of influence and evicting a rival power.9

- Market Upside? Ironically, Russia may benefit marginally in the short term. The removal of Venezuelan oil from the “shadow market” reduces competition for Russian Urals crude in India and China, potentially allowing Russia to command a higher price from these buyers.31

5.2 Iran: Loss of a Strategic Node

The relationship between Caracas and Tehran was symbiotic, driven by mutual isolation.

- Condensate Swaps: The trade mechanism involved Iran sending condensate (a light oil needed to dilute Venezuela’s sludge-like crude) in exchange for Venezuelan heavy oil.32 This allowed both nations to sustain production. With US control of the import terminals, this swap is impossible, furthering the degradation of whatever Venezuelan production capacity remains in the short term.

- Sanctions Evasion Hub: Venezuela served as a “laundromat” for Iranian oil—a place to re-flag vessels, transfer cargoes, and obscure the origin of crude destined for global markets. The loss of PDVSA infrastructure removes a critical node in this network, forcing Iran to restructure its evasion logistics at significant cost.33

- Financial Loss: Iran’s documented $2 billion in loans/projects (housing, car manufacturing) and undocumented military cooperation debts are likely unrecoverable.34

6. North American Energy Architecture

The re-integration of Venezuela into the US energy orbit is the most significant structural shift in the North American energy market since the Shale Revolution.

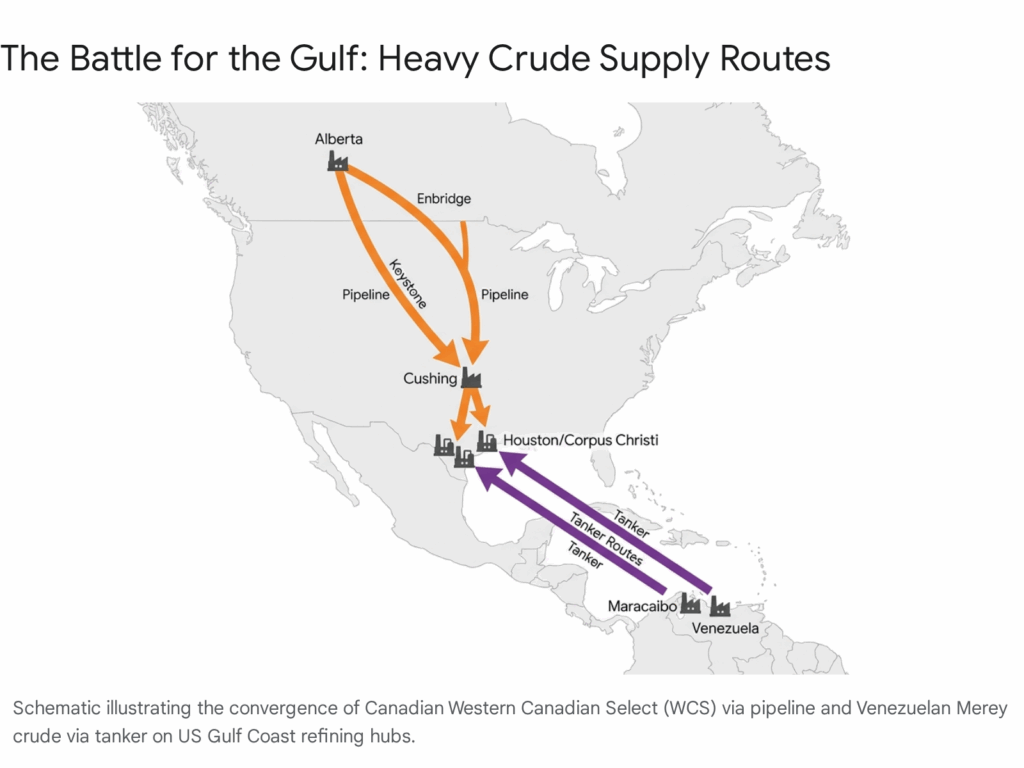

6.1 The US Gulf Coast: The Natural Home for Heavy Crude

The US Gulf Coast (USGC) refining complex is the world’s largest consumer of heavy, sour crude. These refineries (owned by Valero, Marathon, and Citgo) invested billions in “coking” capacity specifically to process Venezuelan oil. Since the sanctions in 2019, they have had to source suboptimal replacements from Russia (before 2022) or compete for limited Canadian barrels.

- Refinery Optimization: The return of Venezuelan Merey crude is a massive boon for US refiners. It allows them to optimize their slates, producing higher margins of diesel and jet fuel. Citgo, a US-based subsidiary of PDVSA, is particularly well-positioned to reintegrate this supply chain.35

- Citgo’s Fate: The ownership of Citgo is currently entangled in court battles over Venezuela’s defaulted bonds. A US-led “trusteeship” might pause the breakup of Citgo, preserving it as the downstream arm of the reconstructed Venezuelan oil industry to ensure refining capacity for the new production.

6.2 The “Loser”: Canadian Oil Sands

The primary economic casualty of Venezuela’s return, outside of the Axis of Resistance, is Canada.

- Competition: Canadian Western Canadian Select (WCS) is a direct competitor to Venezuelan Merey. Both are heavy, sour crudes. Currently, Canada enjoys a near-monopoly on heavy crude imports to the US Midwest and Gulf Coast due to the absence of Venezuelan barrels.

- Price Impact: As Venezuelan volumes ramp up (in the medium term), they will displace heavy crude currently imported from Canada via pipeline and rail. This increased supply competition at the Gulf Coast will likely widen the WCS-WTI differential, effectively lowering the price Canadian producers receive for their oil.36

- Strategic Imperative: This development makes the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion (shipping Canadian oil to Asia) existentially important for the Canadian energy sector, as the US market becomes saturated with “reimbursed” Venezuelan oil.

7. European Ambivalence and the Atlantic Rift

The reaction from Europe highlights a growing rift in the transatlantic alliance, torn between adherence to international law and energy pragmatism.

7.1 Diplomatic Fracture

European leaders have been visibly uncomfortable with the unilateral nature of the US operation.

- Spain: As the former colonial power and a major investor, Spain has led the condemnation. Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, along with leaders from Mexico and Colombia, issued a joint statement rejecting the military operation as a violation of international law.37 This reflects domestic political pressure from left-wing coalition partners but also genuine concern over the precedent of “gunboat diplomacy.”

- United Kingdom: The UK response has been notably cautious. Prime Minister Keir Starmer has distanced London from the operation (“we were not involved”) but stopped short of condemnation, prioritizing the “special relationship” and potential energy security benefits.39

- Italy: The Italian government, led by Giorgia Meloni, offered a more supportive stance, framing the action as “legitimate self-defense” against narco-trafficking, likely reflecting Italy’s own hardline stance on organized crime and desire for close ties with the US administration.37

7.2 The Energy Compromise: Repsol and Eni

The key variable for Europe is the fate of its energy majors, Repsol (Spain) and Eni (Italy). Unlike US firms, these companies maintained operations in Venezuela through “oil-for-debt” swaps authorized by the US State Department.

- Debt Holdings: Eni is owed approximately $2.3 billion, and Repsol is owed roughly €586 million.40

- Future Status: The US administration faces a choice. It can subordinate these claims (lumping them with China/Russia) or offer a “transatlantic compromise” where Repsol and Eni are allowed to remain as junior partners to US operators. Given the need for technical expertise and political cover, it is likely that the US will allow these firms to continue lifting oil, provided they adhere to the strict “trusteeship” revenue rules. This creates a wedge: Spain may condemn the invasion politically, but its flagship company will likely participate in the economic aftermath.

8. Regional Ripple Effects: Latin America

The intervention has shattered the unspoken norms of Latin American sovereignty, forcing regional powers to realign.

8.1 Colombia: The Border Crisis

Colombia faces the most complex fallout.

- Short-term Crisis: The immediate aftermath involves a security crisis on the border. Remnants of the Maduro regime, armed “Colectivos,” and ELN guerrillas may flee into the porous border regions, destabilizing Colombian security.41

- Long-term Gain: However, if the US-led stabilization succeeds, Colombia stands to gain the most. A recovering Venezuelan economy would reverse the migration flow, alleviating the burden of the 2.8 million Venezuelan refugees currently straining Colombia’s social services. The reopening of trade would also revitalize the Colombian border economy.42

8.2 Guyana: The End of the Essequibo Threat

For Guyana, the US intervention is an unmitigated security guarantee. The Maduro regime had increasingly threatened to annex the oil-rich Essequibo region. With the US military effectively guaranteeing the new Venezuelan government, this territorial threat vanishes. The US will likely broker a diplomatic freeze on the dispute to ensure stability for ExxonMobil, which operates massive offshore fields in both Guyana and Venezuela.

8.3 India: The Forgotten Stakeholder

India remains a silent but significant loser. Indian state companies ONGC Videsh and Indian Oil Corp have entitlements to Venezuelan oil.43 Like China, India invested in Venezuela to diversify its energy security. These assets are now in limbo. However, unlike China, India is a strategic partner of the US. We anticipate a diplomatic workaround where Indian firms may be compensated or allowed to retain passive stakes, provided the oil flows are transparent and do not support “Axis” interests.

9. The Financial Warfare Precedent: Mechanism of Control

The US strategy relies on a novel combination of domestic legal frameworks and raw power to reshape the Venezuelan economy.

9.1 The “Odious Debt” Weapon

To make the economics of rebuilding work, the US cannot service Venezuela’s existing ~$150 billion debt mountain. We anticipate the US will encourage the new transitional government to declare debts incurred by the Maduro regime (especially to China and Russia) as “Odious Debt”.

- Legal Theory: The doctrine of Odious Debt holds that debt incurred by a despotic regime for purposes that do not serve the best interests of the nation should not be enforceable against the people of that nation after the regime falls.44

- Application: Legal opinions will likely argue that loans from China and Russia sustained an illegitimate “narco-terrorist” regime and are therefore personal liabilities of the Maduro clique.

- Impact: This would theoretically clear the balance sheet for US investors. However, it is a “nuclear option” in sovereign finance that would trigger years of litigation in New York and London courts and potentially chill Chinese lending to other developing nations.

Table 1: The Creditor Hierarchy Under US Trusteeship

| Creditor Category | Estimated Debt | Likely Status Under Trusteeship | Strategic Rationale |

| US Majors (Exxon/Conoco) | ~$15 Billion | Priority Recovery | “Reimbursement” for expropriation; crucial for technical reentry. |

| Bondholders (Wall St) | ~$60 Billion | Restructured | Likely hair-cut but recognized to maintain access to capital markets. |

| China (Loans-for-Oil) | ~$12-20 Billion | At Risk / “Odious” | Viewed as sustaining the adversary; likely subordinated or voided. |

| Russia (Rosneft/State) | ~$3-5 Billion | Voided | Treated as hostile state financing; total write-down expected. |

| Commercial Suppliers | ~$15 Billion | Case-by-Case | Essential suppliers paid; others written off. |

9.2 The Role of OFAC

The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) will pivot from sanctions enforcement to being the gatekeeper of the Venezuelan economy.

- Licensing: Instead of general licenses, OFAC will issue specific licenses to US-aligned firms to enter and operate.

- Revenue Escrow: Oil revenues will likely be deposited into US-controlled escrow accounts (similar to the Iraq “Oil-for-Food” mechanism but more restrictive) to ensure funds are used strictly for approved “reimbursement” and humanitarian aid, bypassing any remaining Chavista bureaucracy.45

10. Conclusion and Future Outlook

The US operation in Venezuela signifies the end of the post-Cold War era of “soft power” in the Western Hemisphere and the beginning of an era of Resource Realism.

For the Venezuelan People: This intervention promises a potential end to the humanitarian disaster of the last decade, but at the cost of national sovereignty. The country faces a long, painful economic trusteeship where its primary resource is mortgaged to pay for its own “liberation.”

For Global Energy Markets: The “Venezuela Premium” (risk of supply disruption) is replaced by the “Reconstruction Lag.” The world will not be flooded with Venezuelan oil tomorrow. The technical reality of the degraded fields means supply will return slowly, over a decade. However, by 2030, a US-aligned Venezuela could act as a significant counterweight to OPEC+ discipline, cementing North American energy dominance for the mid-21st century.

For Geopolitics: The message to US adversaries is stark: economic investments in the US “near-abroad” are insecure and subject to forcible liquidation. China and Russia have learned that without the ability to project military force to protect them, their financial assets in the Western Hemisphere are vulnerable to the stroke of a pen—or the arrival of a carrier strike group.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- Trump suggests US taxpayers could reimburse oil firms for Venezuela investment, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2026/jan/06/trump-us-taxpayers-oil-firms-venezuela-investment

- Machado welcomes ‘huge step for humanity’ – as it happened, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/world/live/2026/jan/05/venezuela-live-updates-trump-us-interim-president-collaborate

- US: Oil and energy companies’ shares rise after intervention in Venezuela, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/us-oil-and-energy-companies-shares-rise-after-intervention-in-venezuela/

- Chevron Resumes Exports of Venezuelan Oil to US fter Four-Day Pause – Marine Link, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.marinelink.com/news/chevron-resumes-exports-venezuelan-oil-us-534027

- US announces additional sanctions on four oil companies amid Venezuela tensions, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.jurist.org/news/2026/01/us-announces-additional-sanctions-on-4-venezuela-oil-companies-amid-maduro-crackdown/

- Treasury Targets Oil Traders Engaged in Sanctions Evasion for Maduro Regime, accessed January 6, 2026, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sb0348

- Venezuela crude flows slow, Cuba feels sting | Latest Market News, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.argusmedia.com/en/news-and-insights/latest-market-news/2766638-venezuela-crude-flows-slow-cuba-feels-sting

- How Trump’s Venezuela Takeover Could Change the World, accessed January 6, 2026, https://time.com/7343019/venezuela-trump-oil-china/

- The ‘Putinization’ of US foreign policy has arrived in Venezuela, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/03/putin-russia-us-foreign-policy-venezuela

- Venezuela: The Post-Maduro Oil, Gas and Mining Outlook, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/venezuela-the-post-maduro-oil-gas-and-mining-outlook/

- Venezuela oil plan: Donald Trump’s takeover idea unlikely to shift global prices soon; analysts flag hurdles, accessed January 6, 2026, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/international-business/venezuela-oil-plan-donald-trumps-takeover-idea-unlikely-to-shift-global-prices-soon-analysts-flag-hurdles/articleshow/126337786.cms

- Venezuela moves to cut oil output due to US export embargo, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/companies-markets/energy-commodities/venezuela-moves-cut-oil-output-due-us-export-embargo

- Why Venezuela Struggles to Produce Oil Despite Having the World’s Largest Reserves, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.investopedia.com/why-does-venezuela-struggle-with-oil-production-despite-having-the-worlds-largest-reserves-11879080

- Oil spills in Venezuela – pdvsa ad hoc, accessed January 6, 2026, https://pdvsa-adhoc.com/en/2025/06/oil-spills-in-venezuela/

- After U.S. military action in Venezuela, Trump talks about his future plans, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.local10.com/news/world/2026/01/05/after-us-military-action-in-venezuela-trump-talks-about-his-future-plans/

- U.S. seeks to tap Venezuela’s vast oil reserves after military strikes. Here’s what to know., accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/venezuela-oil-reserves-us-strike-trump-what-to-know/

- Why oil-rich Venezuela pumps under 1% of global crude and can Trump push it?, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.indiatoday.in/world/story/venezuela-oil-production-collapse-reasons-oil-rich-reserves-trump-us-companies-feasibility-investment-2846742-2026-01-05

- Explainer: Status of Foreign Oil Companies in Venezuela After Maduro’s Arrest, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.oedigital.com/news/534029-explainer-status-of-foreign-oil-companies-in-venezuela-after-maduro-s-arrest

- US Sets Terms for Oil Giants in Venezuela: Invest First, Get Paid Later – Gotrade, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.heygotrade.com/en/news/us-sets-terms-for-oil-giants-in-venezuela-invest-first-get-paid-later/

- Former Chevron executive seeks $2 billion for oil projects in Venezuela, accessed January 6, 2026, https://americanbazaaronline.com/2026/01/06/former-chevron-executive-seeks-2-billion-venezuela-oil-472665/

- Cuba is said to face potential breakdown as U.S. squeezes Venezuelan oil (CO1:COM:Commodity), accessed January 6, 2026, https://seekingalpha.com/news/4533853-cuba-is-said-to-face-potential-breakdown-as-u-s-squeezes-venezuelan-oil

- Is Cuba next after Maduro’s capture?, accessed January 6, 2026, https://asiatimes.com/2026/01/is-cuba-next-after-maduros-capture/

- Cuba hit with fifth blackout in less than a year with 10m people in the dark – The Guardian, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/sep/10/cuba-electricity-power-blackout

- Maduro’s capture puts Cuba’s Venezuelan oil-dependent economy at risk, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.foxbusiness.com/economy/maduros-capture-puts-cubas-venezuelan-oil-dependent-economy-risk

- For a long time, China has been Venezuela’s largest creditor | 破产哥励志重来 on Binance Square, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.binance.com/en-AE/square/post/34612653999042

- Markets Pivot as Venezuela Geopolitical Shock Triggers Massive Rotation into Defense and Energy, accessed January 6, 2026, https://markets.financialcontent.com/wral/article/marketminute-2026-1-5-markets-pivot-as-venezuela-geopolitical-shock-triggers-massive-rotation-into-defense-and-energy

- China’s oil investments in Venezuela | BOE Report, accessed January 6, 2026, https://boereport.com/2026/01/05/chinas-oil-investments-in-venezuela/

- Concerns over damage to investment in Venezuela are being cited as the background of China’s increas.. – MK, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.mk.co.kr/en/world/11924858

- China decries U.S. action in Venezuela – even as it guards billions at stake – CNBC Africa, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.cnbcafrica.com/2026/china-decries-u-s-action-in-venezuela-even-as-it-guards-billions-at-stake

- US Intervention in Venezuelan Oil Drives Global Energy Disruption, accessed January 6, 2026, https://discoveryalert.com.au/strategic-petroleum-2026-us-venezuela-oil-disruption/

- Trump’s plan to seize and revitalize Venezuela’s oil industry faces major hurdles, accessed January 6, 2026, https://apnews.com/article/venezuela-oil-prices-trump-0c2c6ede79d550af53e6d3ddb51bfa04

- Venezuelan supply and export scenarios under a US military intervention – Kpler, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.kpler.com/blog/venezuelan-supply-and-export-scenarios-under-a-us-military-intervention

- The US Venezuela operation could have major implications for the Middle East, accessed January 6, 2026, https://thejewishindependent.com.au/us-operation-venezuela-iran-implications

- What the fall of Maduro means for Venezuela’s vast debt to Iran, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.iranintl.com/en/202601055479

- Dense, sticky and heavy: why Venezuelan crude oil appeals to US refineries, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2026/jan/05/venezuelan-crude-oil-appeals-to-us-refineries

- U.S. designs for Venezuelan oil industry put pressure on Canadian oil stocks, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.nsnews.com/the-mix/us-designs-for-venezuelan-oil-industry-put-pressure-on-canadian-oil-stocks-11696839

- Europe’s failure to condemn Trump’s illegal aggression in Venezuela isn’t just wrong – it’s stupid | Nathalie Tocci, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2026/jan/06/europe-venezuela-donald-trump-vladimir-putin

- Spain ‘strongly condemns’ violation of international law in Venezuela, PM says By Reuters, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.investing.com/news/world-news/spain-strongly-condemns-violation-of-international-law-in-venezuela-pm-says-4428569

- The Guardian view on Europe’s response to ‘America first’ imperialism: too weak, too timid | Editorial, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2026/jan/05/the-guardian-view-on-europes-response-to-america-first-imperialism-too-weak-too-timid

- FACTBOX | Where global oil firms stand in Venezuela following Maduro’s capture, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.bairdmaritime.com/offshore/drilling-production/factbox-where-global-oil-firms-stand-in-venezuela-following-maduros-capture

- Regime Change, Minimum Wage Hikes and AI Among the Forces Reshaping Investment in Latin America in 2026 – Ag Plus, Inc. -, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.agplusinc.com/news/story/36873102/regime-change-minimum-wage-hikes-and-ai-among-the-forces-reshaping-investment-in-latin-america-in-2026

- Venezuela: Focus on stability rather than regime change for now – Janus Henderson, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.janushenderson.com/en-us/advisor/article/venezuela-focus-on-stability-rather-than-regime-change-for-now/

- Foreign Claims to Venezuelan Oil in Doubt after US Intervention, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.rigzone.com/news/wire/foreign_claims_to_venezuelan_oil_in_doubt_after_us_intervention-05-jan-2026-182679-article/

- An Economic Framework for Venezuela’s Debt Restructuring – Harvard Kennedy School, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/degree%20programs/MPAID/files/Moatti%2C%20Thomas%20and%20Muci%2C%20Frank%20SYPA.pdf

- Experts react: The US just captured Maduro. What’s next for Venezuela and the region?, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/dispatches/us-just-captured-maduro-whats-next-for-venezuela-and-the-region/