| This is a time-sensitive special report and is based on information available as of January 5, 2026. Due to the situation being very dynamic the following report should be used to obtain a perspective but not viewed as an absolute. |

The January 2026 execution of “Operation Absolute Resolve,” which culminated in the extraction of Nicolás Maduro by United States military forces and the subsequent imposition of a US-administered transitional authority in Caracas, constitutes a geopolitical event of the highest magnitude. While the operation was tactically confined to the Caribbean basin, its strategic shockwaves have registered with immediate and destabilizing force in Beijing. For the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the sudden removal of the Bolivarian government represents a dismantling of a critical node in its Western Hemisphere strategy, a direct threat to tens of billions of dollars in state-backed financial assets, and a forced, costly recalibration of its national energy security architecture.

This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the multi-dimensional impacts radiating from the US takeover of Venezuela. The analysis is anchored in the premise that the “loss” of Venezuela is not merely a diplomatic setback for China, but a systemic shock that challenges the viability of its “resources-for-loans” model, exposes the fragility of its “all-weather” partnerships in the face of American hard power, and creates acute energy supply vulnerabilities for its independent refining sector.

The most immediate operational consequence is the severance of the “shadow fleet” trade that has sustained China’s independent refiners—colloquially known as “teapots”—with deeply discounted heavy crude oil. The imposition of a US-enforced “oil quarantine” has effectively interdicted the flow of Venezuelan Merey 16 crude to Shandong province. This disruption forces Chinese buyers into the open market to compete for increasingly scarce heavy sour grades, such as Western Canadian Select (WCS) and Basra Heavy, thereby eroding the refining margins that underpin the global competitiveness of China’s petrochemical exports. The arbitrage window, closed by the sudden escalation of maritime insurance premiums and the physical diversion of tankers, has precipitated a feedstock crisis that will likely lead to run cuts and consolidation within China’s refining sector.

Financially, Beijing faces the precarious prospect of asset nullification. The China Development Bank (CDB) and other state entities hold an estimated $12 billion to $19 billion in outstanding sovereign debt, historically serviced through direct oil shipments. The US administration’s rhetoric regarding the “rebuilding” of Venezuela implies a legal strategy that may classify these Chinese loans as “odious debt”—liabilities incurred by a despotic regime for purposes contrary to the national interest. Such a classification would legally subordinate Chinese claims to new US capital injections and humanitarian obligations, setting a dangerous precedent for the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). If the “Venezuela Precedent” establishes that regime change can serve as a mechanism for debt erasure, the risk premium on China’s global lending portfolio will face upward revision.

Geopolitically, the operation serves as a forceful modernization of the Monroe Doctrine. The neutralization of the Maduro regime isolates Cuba, Venezuela’s primary regional client, placing Beijing in a strategic bind: it must either finance a massive emergency energy bailout for Havana at a time of domestic economic constraint or witness the destabilization of another socialist ally. Furthermore, while US and international analysts caution against drawing direct parallels to the Taiwan Strait, Chinese strategists will inevitably interpret the “decapitation” strike as a validation of unilateral force to resolve sovereignty disputes, a perception that may accelerate the hardening of China’s anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities.

Ultimately, while the US administration promises a swift revitalization of Venezuela’s oil sector, technical realities suggest a protracted recovery requiring over a decade and upwards of $185 billion in capital. This reconstruction phase offers China a narrow window for asymmetric response, likely leveraging its dominance in critical mineral supply chains to negotiate favorable terms for its stranded assets. However, the strategic reality remains that the US has successfully reclaimed the energy advantage in the Western Hemisphere, forcing China into a defensive posture.

1. Contextualizing Operation Absolute Resolve: The Collapse of a Strategic Anchor

To understand the magnitude of the shock to China, one must first appreciate the depth of the Sino-Venezuelan relationship prior to January 2026. Under the presidencies of Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela served as China’s primary bridgehead in Latin America—a region traditionally viewed as Washington’s sphere of influence. This relationship was formalized in 2023 with the elevation of bilateral ties to an “All-Weather Strategic Partnership,” a diplomatic designation Beijing reserves for its most trusted allies.1

The partnership was underpinned by a strategic exchange: China provided diplomatic cover and liquidity (over $60 billion in loans since 2007) in exchange for secured access to the world’s largest proven oil reserves.2 This arrangement was designed to be sanction-proof, utilizing oil shipments to repay debts, thereby bypassing the US dollar system. The US military intervention has violently dismantled this architecture.

The operation itself, characterized by airstrikes on command-and-control nodes and the targeted extraction of the executive leadership, was executed with a speed that precluded any intervention by external powers.3 For Beijing, the surprise nature of the raid and the subsequent rapid installation of a US-backed transitional authority highlight a critical intelligence and capability gap in protecting its overseas interests. The immediate reaction from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs—expressing “grave concern” and calling for Maduro’s release—reflects a diplomatic posture struggling to catch up with a new reality on the ground.5 The strategic anchor has been weighed, and China has been cut loose.

2. The Energy Dimension: Supply Shock and Market Realignment

The primary transmission mechanism of this geopolitical shock to the Chinese economy is the disruption of the physical oil trade. While Venezuela’s production had fallen significantly from its peak, it remained a vital, albeit opaque, source of heavy crude for China’s industrial engine. The cessation of these flows triggers a cascade of impacts across the global heavy oil market, with the pain concentrated in Shandong province.

2.1 The “Merey” Dependency and the Teapot Crisis

Venezuela’s flagship export grade, Merey 16, is a unique crude: extra-heavy, high in sulfur, and rich in metals. While these characteristics make it unattractive to many simple refineries, it is the ideal feedstock for complex refineries equipped with deep conversion capacity, such as cokers and asphalt plants. China’s independent refiners, the “teapots,” spent the last decade optimizing their kits to process exactly this type of discounted, “distressed” barrel.

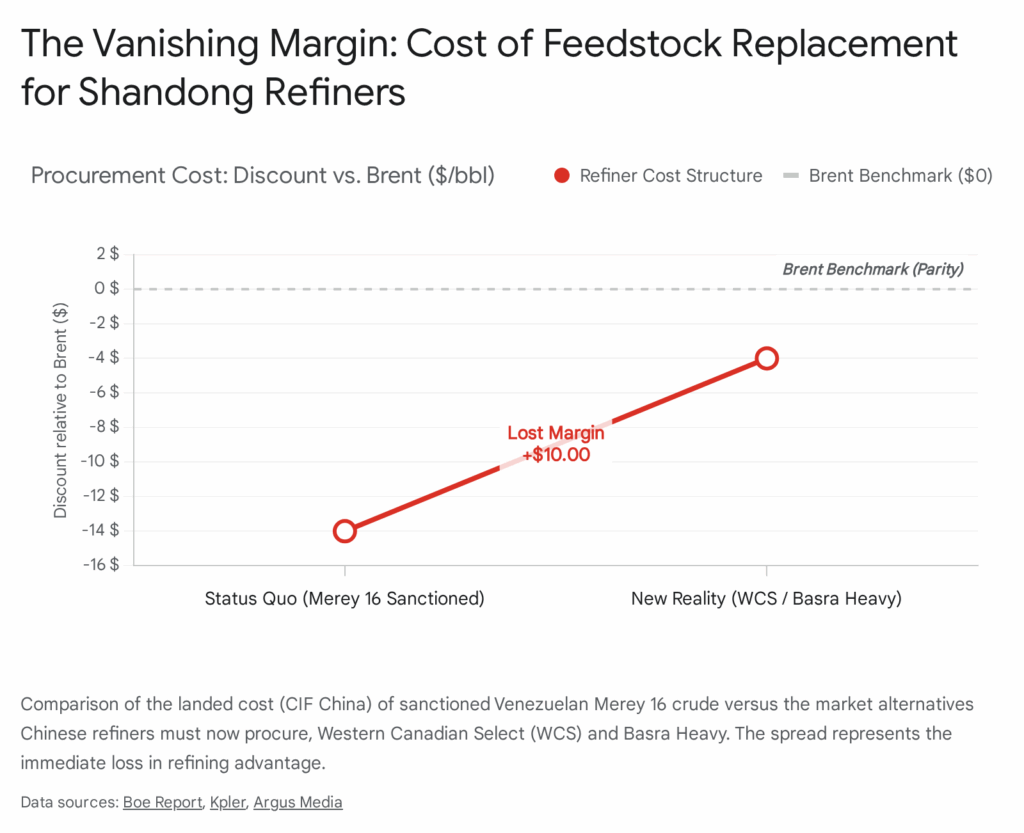

Prior to the intervention, China was importing approximately 470,000 barrels per day (bpd) of Venezuelan crude, which constituted roughly 4.5% of its total seaborne crude imports.2 While this percentage might appear manageable in aggregate, the specific economic reliance was profound. Due to US sanctions, Merey 16 traded at a massive discount—often $10 to $15 per barrel below the Brent benchmark.8 This “sanctions discount” effectively subsidized the margins of independent Chinese refiners, allowing them to remain competitive against state-owned giants like Sinopec and PetroChina, and to export refined products like bitumen and diesel at aggressive prices.

The US takeover has effectively zeroed out this supply. The Trump administration has declared an “oil quarantine,” and the US Treasury has signaled that Venezuelan oil will henceforth be redirected to the US Gulf Coast.4 The Gulf Coast refining complex, comprising majors like Citgo, Valero, and Chevron, was historically designed to process Venezuelan heavy crude and has faced a structural shortage of heavy barrels since the imposition of sanctions in 2019. The redirection of Venezuelan flows to the US is therefore a strategic priority for Washington to suppress domestic gasoline prices, directly at the expense of Chinese buyers.10

The loss of Merey 16 forces Chinese teapots to scramble for substitutes. The only globally traded grades with similar yield profiles are Western Canadian Select (WCS), Mexican Maya, and Iraq’s Basra Heavy. However, these grades trade at market rates, without the deep discounts associated with sanctioned regimes.

As illustrated, the shift from a sanctioned discount to a market premium represents a catastrophic margin compression for the teapot sector. This “sovereignty premium” will likely force a wave of consolidation in Shandong, as smaller, less capitalized refineries fail to absorb the input cost shock.11

2.2 The Liquidation of the Shadow Fleet

The operational backbone of the China-Venezuela oil trade was a clandestine logistics network known as the “shadow fleet”—a flotilla of aging tankers with obscured ownership structures, registered in permissive jurisdictions, and operating often with disabled Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) to evade detection. This fleet facilitated the transfer of crude from Venezuelan ports to transshipment hubs off the coast of Malaysia, where the oil was blended and rebranded as “Malaysian Bitumen Blend” or “Singma Crude” to mask its origin before entering Chinese ports.7

The US “oil quarantine” has rendered this infrastructure toxic. The US Navy, operating under new, robust rules of engagement in the Caribbean, has begun interdicting vessels suspected of carrying “illicit” cargo. The boarding of the tanker “Skipper” and the designation of vessels like the “Nord Star” and “Lunar Tide” as blocked property have sent a shockwave through the maritime insurance market.4

The impact is binary: the trade has stopped. Mainstream protection and indemnity (P&I) clubs had already abandoned the trade, but now even second-tier insurers and “shadow” insurers are retreating due to the existential risk of vessel seizure. Insurance premiums for any vessel entering Venezuelan waters have spiked by 300-400%.14 For Chinese buyers, the logistical arbitrage—the ability to move sanctioned oil cheaply—has collapsed. The shadow fleet vessels, now marked liabilities, are effectively stranded assets, unable to trade in legitimate markets and too risky to deploy in the Caribbean.

2.3 Global Arbitrage and the Canadian Complication

The US seizure of Venezuelan reserves has a secondary, ironic effect on China’s energy security via the Canadian market. With the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion (TMX) coming online, China had begun aggressive purchasing of Canadian heavy crude as a diversification play. However, the redirection of Venezuelan crude to the US Gulf Coast alters the North American balance.

Historically, US Gulf Coast refiners relied on heavy crude from Venezuela, Mexico, and Canada. With Venezuelan volumes offline for years, they became increasingly dependent on Canadian imports. Now, if the US successfully restores Venezuelan production for domestic use, it might theoretically displace Canadian barrels in the Gulf, freeing them up for export to Asia.15

However, in the short-to-medium term (1-3 years), the opposite dynamic is more likely. The reconstruction of Venezuela’s oil sector will be slow (see Section 7), meaning the US Gulf Coast will continue to demand Canadian barrels. Simultaneously, Chinese refiners, starved of Merey 16, will bid aggressively for the same Canadian WCS barrels. This puts Chinese buyers in direct competition with US refiners for Canadian supply, driving up the price of WCS relative to WTI. The widening discount that Chinese buyers enjoyed on Venezuelan oil is replaced by a narrowing discount on Canadian oil due to heightened competition.16 The result is a structurally higher energy import bill for the PRC.

3. The Financial Black Hole: Sovereign Debt and Asset Forfeiture

Beyond the immediate flow of commodities, the US intervention poses a grave threat to China’s financial balance sheet. The “resources-for-loans” model, pioneered by the China Development Bank (CDB) in the mid-2000s, was predicated on the assumption that sovereign control of oil reserves provided the ultimate collateral. The US takeover challenges the validity of this collateral and places billions of dollars in outstanding debt at risk of erasure.

3.1 The “Odious Debt” Weapon

Estimates of Venezuela’s outstanding debt to Chinese entities range from $12 billion to $19 billion.17 This debt was being serviced, albeit inconsistently, through oil shipments that have now been halted by the US blockade. The critical question facing Beijing is not just when payment will resume, but if the legal obligation to pay will survive the transition.

The US administration, in its role as the architect of the post-Maduro order, has indicated a willingness to use “economic leverage” to reshape Venezuela.4 A potent tool in this arsenal is the legal doctrine of “odious debt.” This principle of international law posits that sovereign debt incurred by a despotic regime for purposes that do not benefit the population, and with the creditor’s full knowledge of these facts, is personal to the regime and not enforceable against the state after the regime falls.19

There is a high probability that the US-backed transitional government will argue that Chinese loans extended to the Maduro administration—particularly those post-2017, after the National Assembly was sidelined—constitute odious debt. They may argue these funds sustained an illegitimate “narco-terrorist” regime rather than funding national development.9 If successful, this classification would subordinate Chinese claims in any restructuring process.

Legal precedents from Iraq (post-2003) and Ecuador suggest that while wholesale repudiation is rare, the threat of odious debt classification is often used to force creditors to accept massive haircuts (reductions in principal). For the China Development Bank, this implies a potential write-down of nearly its entire Venezuelan portfolio—a loss that would eclipse any previous BRI failure.21

3.2 Stranded Equity: The Joint Venture Trap

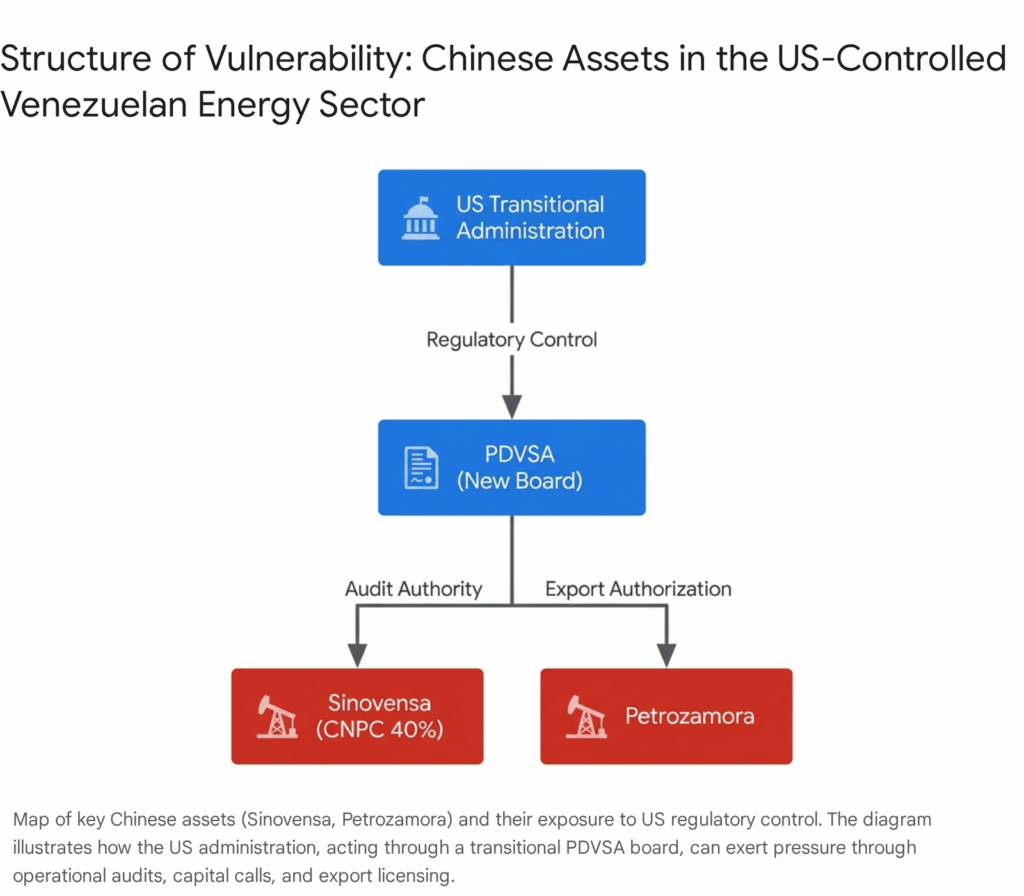

In addition to debt, Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) hold significant equity positions in Venezuelan upstream projects. CNPC and Sinopec are minority partners in joint ventures (JVs) such as Sinovensa, Petrozamora, and Petrourica. Sinovensa alone, a partnership with PDVSA, sits atop 1.6 billion barrels of reserves.22

These assets are now in a precarious position. The US administration has declared that “American companies” will be tasked with revitalizing the industry.3 While formal expropriation of Chinese assets might violate bilateral investment treaties and invite retaliation against US firms in China, the US can achieve a de facto expulsion through regulatory strangulation.

The mechanisms for this “soft expropriation” are manifold:

- Operational Paralysis: The US-controlled PDVSA board can suspend the operational licenses of Chinese JVs pending “corruption audits” or “environmental reviews,” effectively freezing the assets.

- Sanctions Compliance: The US Treasury can maintain sanctions on specific JVs involving Chinese entities, preventing them from accessing the US financial system or importing essential diluents, while granting waivers to US-partnered JVs.

- Capital Call Dilution: The reconstruction of these fields requires massive capital injection. The new PDVSA board could issue capital calls for repairs. If Chinese partners cannot transfer funds due to US financial sanctions or internal risk aversion, their equity stakes would be diluted, eventually rendering them negligible.23

This strategy forces China into a “wait and see” posture. Chinese firms are unlikely to abandon their stakes voluntarily, but they may be forced into a dormant status, holding paper titles to assets they cannot operate or monetize, while US firms like Chevron and potential returnees like ExxonMobil assume operational dominance.

4. Geopolitical Repercussions: The Monroe Doctrine Revived

The US operation represents a definitive reassertion of the Monroe Doctrine—the 19th-century policy opposing external intervention in the Americas—modernized for the era of great power competition. For two decades, China has cultivated Venezuela as a strategic partner to counterbalance US influence in the Asia-Pacific. The “loss” of Venezuela effectively pushes China back across the Pacific, dismantling its most significant foothold in the Western Hemisphere.

4.1 The Collapse of the “All-Weather” Partnership

In September 2023, President Maduro visited Beijing, where he and President Xi Jinping signed a joint statement elevating relations to an “All-Weather Strategic Partnership”.1 This diplomatic tier implies a relationship that remains stable regardless of the international landscape. The capture of Maduro fundamentally invalidates this status. It demonstrates to the world, and particularly to other “Global South” nations, that Beijing cannot guarantee the security or political survival of its partners in the US “near abroad.”

This creates a crisis of confidence for other nations in the region that have courted Chinese investment, such as Bolivia, Nicaragua, and even Brazil under leftist leadership. The message from Washington is unequivocal: economic alignment with Beijing offers no shield against US security interests. This chilling effect may stall the expansion of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) across Latin America, as governments reassess the political risk of antagonizing Washington. The “Venezuela Model”—high-risk lending for resource access—is now visibly broken.2

4.2 The Cuban Dilemma: A Crisis on the Doorstep

The impact on Cuba is collateral but catastrophic, presenting Beijing with an acute strategic dilemma. Venezuela has been Havana’s economic lifeline for two decades, providing roughly 50,000 to 60,000 barrels of oil per day at subsidized rates or in exchange for services (doctors, intelligence). This oil kept Cuba’s fragile power grid functioning and its economy afloat. The cessation of these shipments precipitates an existential energy crisis for the Cuban government, with experts predicting “total national blackouts” within weeks.25

China is the only power capable of filling this void, but the costs are prohibitive. To replace Venezuelan supply, China would need to ship oil halfway around the world, incurring massive logistical costs. Furthermore, any direct “bailout” of Cuba would almost certainly trigger US secondary sanctions on the Chinese entities involved, given the US administration’s aggressive posture.

Beijing faces a binary choice:

- Intervene: Provide emergency oil and credit to stabilize the Cuban regime. This preserves a strategic ally and signals reliability to partners, but risks a direct escalation with the US during a delicate transition period and strains China’s own slowing economy.

- Abstain: Allow the Cuban crisis to unfold. This avoids US retaliation but risks the collapse of another socialist ally and confirms the “paper tiger” narrative regarding China’s ability to project power in the Americas.

Analysts suggest China will likely pursue a middle path: providing limited humanitarian aid and symbolic support while avoiding a full-scale energy bailout, effectively ceding the strategic initiative to the US.26

4.3 Strategic Signaling and the Taiwan Question

While US officials and international scholars caution against drawing direct parallels between Venezuela and Taiwan due to vastly different historical, legal, and military contexts, the psychological impact on Beijing is profound.2 The operation demonstrates the US willingness to execute a “decapitation” strategy—removing a leadership circle to effect regime change—and to use military force against a sovereign state to secure resource interests.

In Beijing, this reinforces the “Fortress China” mentality. It validates the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) focus on anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities to prevent a similar projection of US power near its shores. It may also accelerate China’s efforts to sanction-proof its own economy and leadership, knowing now that the US toolkit includes direct physical abduction of heads of state.

However, contrary to fears of immediate escalation, China’s response regarding Taiwan is likely to be cautious. The speed and efficacy of the US operation in Venezuela highlight the risks of a conflict with the US military. This may lead Beijing to double down on “gray zone” tactics—coercion below the threshold of war—rather than risking a military adventure that could invite a decisive US counter-response. The “Venezuela shock” is likely to induce a period of strategic reassessment in Beijing rather than immediate aggression.28

5. Diplomatic and Legal Warfare: The Battle for Narrative

Lacking the military capacity to challenge the US in the Caribbean, China represents its interests through diplomatic and legal channels. The battle for the narrative—defining the legitimacy of the US intervention and the status of Venezuela’s obligations—is now the primary front of resistance for Beijing.

5.1 The UN Security Council and the “Global South”

China has strongly condemned the US operation as a “blatant violation of international law” and the UN Charter.5 At the UN Security Council, China, likely in coordination with Russia, will block any resolution that attempts to legitimize the US-installed transitional government. While the US does not need a UN resolution to maintain control on the ground, the lack of international legal recognition complicates the new government’s ability to access Venezuelan assets frozen abroad (e.g., gold in London) or to participate in formal multilateral institutions.29

China will use this platform to rally the “Global South,” framing the US action as a return to imperialist gunboat diplomacy. This narrative is designed to damage US soft power and consolidate China’s standing as the defender of national sovereignty and non-interference—core tenets of its foreign policy. This diplomatic obstructionism serves to delegitimize the US presence and raise the reputational cost of the occupation.30

5.2 Asymmetric Response: The Rare Earths Option

If the US moves to fully nullify Chinese assets in Venezuela, Beijing retains asymmetric economic options. The most potent of these is its dominance in the critical minerals supply chain. China controls approximately 90% of global rare earth refining capacity, materials essential for US defense technologies (including the very precision-guided munitions used in Venezuela) and, ironically, for the catalysts used in oil refining.2

China could implement stricter export controls on processed heavy rare earths, citing “national security” or “environmental compliance.” This would be a direct tit-for-tat response: “You squeeze our energy access; we squeeze your technology supply chain.” This lever is one of the few direct economic tools China has that can inflict pain on the US industrial base without triggering a full-scale kinetic conflict.

6. Future of Venezuelan Oil: The US Quagmire and the Long Road to Recovery

The US administration’s narrative suggests a rapid revitalization of the Venezuelan oil sector, with US majors “fixing” the broken infrastructure and flooding the market with crude.3 However, technical and economic realities suggest a much slower, more difficult path—a reality that China is undoubtedly calculating.

6.1 The Technical Reality: Decay and Capital Intensity

Venezuela’s oil infrastructure is in a state of advanced decay. Production has collapsed from 3.5 million bpd in 1997 to roughly 900,000 bpd today.32 Pipelines are rusted, reservoirs have been damaged by poor management (e.g., shutting in wells without proper procedure), and the sector has suffered a massive brain drain of technical talent.

Restoring this capacity is a monumental engineering task. Analysis by Rystad Energy estimates that returning production to 3 million bpd would require 16 years of sustained effort and $185 billion in capital investment.33 In the short term—the next 12 to 24 months—production is actually likely to fall or stagnate. The new US administration will need to purge the sector of Maduro loyalists, audit operations, and secure facilities against sabotage. The “immediate windfall” is a political fiction; the reality is a decade-long slog.

Table 1: The Reality Gap in Venezuelan Oil Reconstruction

| Metric | US Political Narrative | Technical/Industry Forecast |

| Recovery Timeline | Immediate (“months”) | 10-16 Years to reach 3M bpd |

| Capital Requirement | “Self-funding” via oil sales | $180B – $200B external injection needed |

| Production Trajectory | Rapid V-shaped recovery | L-shaped or slow incremental growth |

| Key Constraints | Political will (“regime change”) | Infrastructure rot, labor shortage, reservoir damage |

| Investor Appetite | “Billions” from US majors | Cautious; demand for legal certainty & debt settlement |

Data derived from Rystad Energy 33, Wood Mackenzie 4, and industry analyst consensus.31

6.2 The Reluctance of US Majors

While President Trump has called for US companies to “go in,” the majors themselves—ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, and Chevron—are cautious. Exxon and Conoco have outstanding arbitration claims against Venezuela totaling billions of dollars from the Chavez-era expropriations.35 They will likely demand that these “legacy claims” be settled—perhaps through “sweat equity” or favorable royalty terms—before committing fresh capital.

This creates a closed loop where early oil revenues are diverted to pay off old US debts rather than funding reconstruction or state services. For China, this delay is strategically relevant. It means the “flood” of Venezuelan oil to the US Gulf Coast will not happen overnight. The global oil market will remain tight, and prices—including the Canadian WCS prices China must now pay—will remain elevated. This buys China time to secure alternative supplies, but it confirms that Venezuelan oil will be locked into the US sphere of influence for the foreseeable future.

7. Strategic Conclusions and Future Scenarios

The US seizure of Venezuela is a watershed moment that forces a fundamental restructuring of China’s approach to the Western Hemisphere. The era of the “All-Weather Partnership” fueled by loans-for-oil is effectively over.

7.1 Scenario A: The “Odious Debt” Precedent

If the US successfully guides the new Venezuelan administration to repudiate Chinese loans using the “odious debt” doctrine, the ripple effects will be global.

- Mechanism: Legal classification of 2017-2025 loans as illegitimate and non-beneficial to the state.

- Impact: A $19 billion write-down for Chinese state banks. More critically, it forces China to tighten lending terms for all BRI projects globally, demanding sovereign immunity waivers and tangible collateral outside the borrower country (e.g., ports), potentially sparking political backlash in Africa and Asia.

- China’s Move: Beijing blocks Venezuela from accessing assets in jurisdictions where it has sway and utilizes the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) to creating alternative norms that reject this classification.

7.2 Scenario B: The Asymmetric Standoff

China links energy access to technology access.

- Mechanism: Beijing restricts exports of heavy rare earths or battery precursors to the US, citing the Venezuela intervention as a destabilizing act that requires “defensive” supply chain measures.

- Impact: A potential “Grand Bargain” where China accepts a haircut on Venezuelan debt in exchange for continued access to certain mineral markets or US restraint in other theaters (e.g., tech sanctions).

7.3 Conclusion: The Defensive Pivot

Ultimately, China’s response will be defined by pragmatism. Unable to contest the US military fait accompli in the Caribbean, Beijing will pivot to damage control: securing what financial assets it can through international courts, diversifying its heavy oil sources to mitigate the price shock, and reinforcing its remaining partnerships in the Global South against similar “interventionist” risks. The “Caracas Pivot” marks the end of China’s offensive expansion in Latin America’s energy sector and the beginning of a defensive consolidation of its global supply lines.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- Maduro’s downfall puts China’s relationship with Venezuela to the test, accessed January 6, 2026, https://english.elpais.com/international/2026-01-04/maduros-downfall-puts-chinas-relationship-with-venezuela-to-the-test.html

- What the US capture of Maduro means for China’s interests in Venezuela and beyond – CNA, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/east-asia/us-venezuela-capture-maduro-china-latin-america-taiwan-implications-5817086

- Trump’s plan to seize and revitalize Venezuela’s oil industry faces major hurdles – AP News, accessed January 6, 2026, https://apnews.com/article/venezuela-oil-prices-trump-0c2c6ede79d550af53e6d3ddb51bfa04

- Venezuela regime change: what it means for oil production, crude and product markets, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.woodmac.com/news/opinion/venezuela-regime-change-what-it-means-for-oil-production-crude-and-product-markets/

- Foreign Ministry Spokesperson’s Remarks on the U.S. Seizing Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and His Wife, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/xw/fyrbt/202601/t20260104_11797389.html

- U.S.-Venezuela tensions: China says U.S. should immediately release Venezuela’s Maduro, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/china-says-us-should-immediately-release-venezuelas-maduro/article70470228.ece

- China’s oil investments in Venezuela – The Economic Times, accessed January 6, 2026, https://m.economictimes.com/news/international/world-news/chinas-oil-investments-in-venezuela/articleshow/126354640.cms

- Venezuela forced to double discount on oil to Asia due to flood of sanctioned crude, accessed January 6, 2026, https://boereport.com/2025/12/10/venezuela-forced-to-double-discount-on-oil-to-asia-due-to-flood-of-sanctioned-crude/

- US imposes sanctions on 4 Venezuelan oil firms and 4 more tankers in Maduro crackdown, accessed January 6, 2026, https://apnews.com/article/sanctions-oil-tankers-venezuela-trump-maduro-9ffee61472d248aafdc9d9bef6195c2e

- US Refiners Win, China Loses in Trump’s Venezuela Oil Play – Offshore Engineer Magazine, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.oedigital.com/amp/news/534004-us-refiners-win-china-loses-in-trump-s-venezuela-oil-play

- Sanctions shake up $20B Chinese refinery, western partners pull out – The Economic Times, accessed January 6, 2026, https://m.economictimes.com/news/international/world-news/sanctions-shake-up-20b-chinese-refinery-western-partners-pull-out/articleshow/125588331.cms

- Why Did the United States Seize a Venezuelan Oil Shipment? – CSIS, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.csis.org/analysis/why-did-united-states-seize-venezuelan-oil-shipment

- Treasury Targets Oil Traders Engaged in Sanctions Evasion for Maduro Regime, accessed January 6, 2026, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sb0348

- US Intervention in Venezuelan Oil Drives Global Energy Disruption – Discovery Alert, accessed January 6, 2026, https://discoveryalert.com.au/strategic-petroleum-2026-us-venezuela-oil-disruption/

- Western Canada Select widens; Venezuela a longer-term risk, analysts say – BOE Report, accessed January 6, 2026, https://boereport.com/2026/01/05/western-canada-select-widens-venezuela-a-longer-term-risk-analysts-say/

- Heavy sour Canadian grades feel pressure in N America | Latest Market News, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.argusmedia.com/en/news-and-insights/latest-market-news/2771891-heavy-sour-canadian-grades-feel-pressure-in-n-america

- Maduro capture: What’s at stake for China’s economic interests in Venezuela, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/international/maduro-capture-whats-stake-chinas-economic-interests-venezuela

- Maduro, Venezuela, the U.S.—and the oil shock China can’t price in | Probe International, accessed January 6, 2026, https://journal.probeinternational.org/2026/01/05/maduro-venezuela-the-u-s-and-the-oil-shock-china-cant-price-in/

- Systemic Illegitimacy, Problems, and Opportunities in Traditional Odious Debt Conceptions in Global, accessed January 6, 2026, https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1439&context=lcp

- Venezuela’s Economic Crisis: Issues for Congress – EveryCRSReport.com, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R45072.html

- An Economic Framework for Venezuela’s Debt Restructuring – Harvard Kennedy School, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/degree%20programs/MPAID/files/Moatti%2C%20Thomas%20and%20Muci%2C%20Frank%20SYPA.pdf

- China’s Oil Investments in Venezuela – Energy News, Top Headlines, Commentaries, Features & Events – EnergyNow.com, accessed January 6, 2026, https://energynow.com/2026/01/chinas-oil-investments-in-venezuela/

- Concerns over damage to investment in Venezuela are being cited as the background of China’s increas.., accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.mk.co.kr/en/world/11924858

- US actions signal a return to imperialism, colonialism – Opinion – Chinadaily.com.cn, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202601/04/WS695a2881a310d6866eb31d6c.html

- ‘Got free oil from Venezuela’: Why Cuba’s collapse looks inevitable after capture of Nicholas Maduro – WION, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.wionews.com/photos/-got-free-oil-from-venezuela-why-cuba-s-collapse-looks-inevitable-after-capture-of-nicholas-maduro-1767531151243

- China decries U.S. action in Venezuela – even as it guards billions at stake – CNBC Africa, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.cnbcafrica.com/2026/china-decries-u-s-action-in-venezuela-even-as-it-guards-billions-at-stake/

- U.S. strike in Venezuela unlikely to alter China’s Taiwan strategy: Scholars, accessed January 6, 2026, https://focustaiwan.tw/politics/202601040007

- ‘Dangerous Precedent’: Southeast Asia’s Response to US Venezuela Intervention, accessed January 6, 2026, https://thediplomat.com/2026/01/dangerous-precedent-southeast-asias-response-to-us-venezuela-intervention/

- Venezuela: Emergency Meeting : What’s In Blue, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/whatsinblue/2026/01/venezuela-emergency-meeting.php

- U.S. Seizure of Maduro Challenges China’s Non-Intervention Diplomacy, accessed January 6, 2026, https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2026/01/06/u-s-seizure-of-maduro-challenges-chinas-non-intervention-diplomacy/

- What role could the US play in Venezuela’s ‘bust’ oil industry?, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2026/jan/04/venezuela-oil-industry-bust-what-role-could-the-us-play

- President Trump Wants Investments in Venezuelan Oil: What Are the Challenges? – AAF, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/president-trump-wants-investments-in-venezuelan-oil-what-are-the-challenges/

- Dense, sticky and heavy: why Venezuelan crude oil appeals to US refineries – The Guardian, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2026/jan/05/venezuelan-crude-oil-appeals-to-us-refineries

- Venezuela needs $183bn to revive oil output, Rystad says – Energy Voice, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.energyvoice.com/oilandgas/americas/589136/venezuela-needs-183bn-to-revive-oil-output-rystad-says/

- U.S. oil companies won’t rush to re-enter shaky Venezuela, experts say, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/venezuela-oil-maduro-chevron-exxon-mobil-conocophiillips/

- ConocoPhillips loses Venezuela compensation case | Latest Market News – Argus Media, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.argusmedia.com/es/news-and-insights/latest-market-news/1952532-conocophillips-loses-venezuela-compensation-case