| This is a time-sensitive special report and is based on information available as of January 5, 2026. Due to the situation being very dynamic the following report should be used to obtain a perspective but not viewed as an absolute. |

The decisive execution of Operation Absolute Resolve in January 2026, culminating in the capture of Nicolás Maduro and the assertion of United States administrative control over Venezuela’s energy sector, constitutes a catastrophic strategic reversal for the Russian Federation.1 This event is not merely the displacement of a localized ally; it represents the systematic dismantling of Moscow’s primary forward operating base in the Western Hemisphere and the foreclosure of a multi-decade geopolitical project intended to challenge US hegemony in its “near abroad”.3

The ramifications for Russia are multidimensional and severe. Operationally, the failure of Russian intelligence and military advisors to secure the Maduro regime exposes a critical weakness in the Kremlin’s security guarantees, damaging its reputation among client states globally.3 Financially, the imposition of a US-backed interim administration places billions of dollars in Russian state-backed loans and energy assets—transferred to the state-owned entity Roszarubezhneft to avoid sanctions—at imminent risk of expropriation or devaluation.6

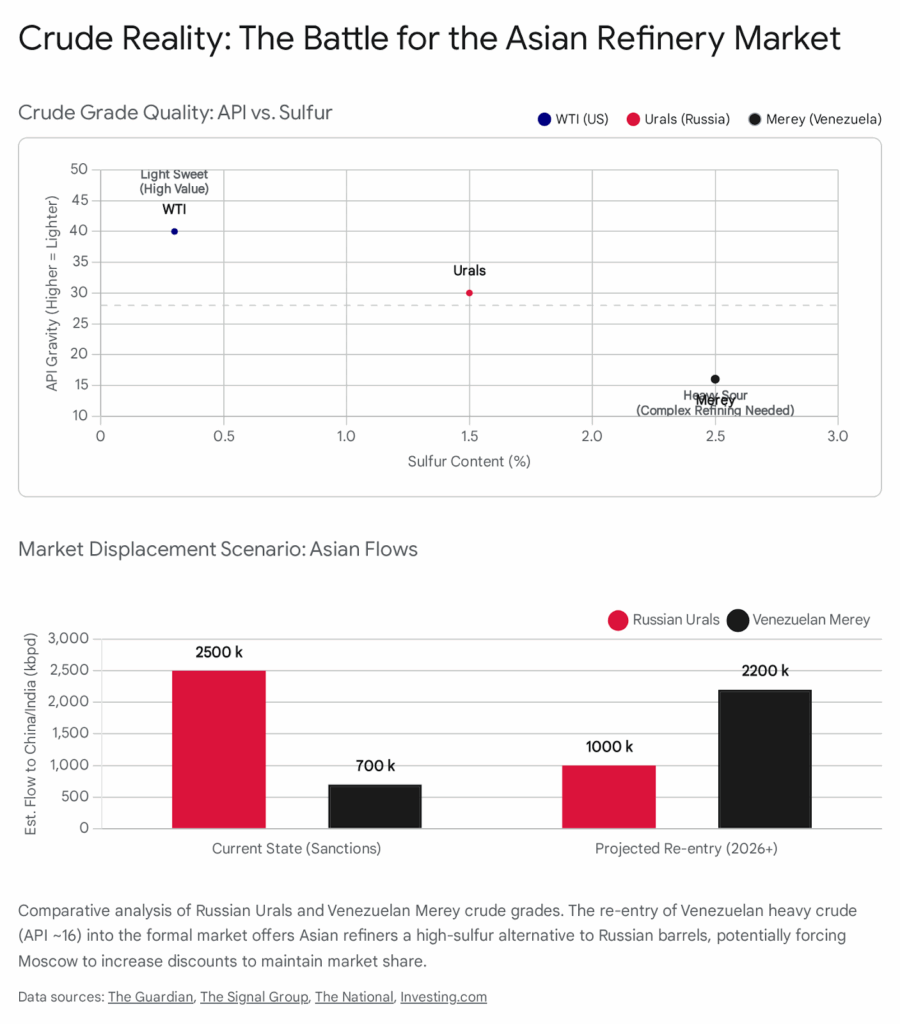

However, the most profound threat lies in the global energy markets. The US seizure of Venezuela’s oil infrastructure threatens to fundamentally reorder the heavy crude supply chain. As US majors move to rehabilitate the dilapidated Venezuelan sector, the reentry of “legitimate” heavy crude—specifically targeting refineries in the US Gulf Coast and eventually Asia—poses a direct competitive threat to Russia’s Urals export blend. The Urals blend, currently Russia’s economic lifeline amidst the war in Ukraine, faces displacement in key markets like India and China, forcing Moscow to deepen discounts and further erode its war chest.8

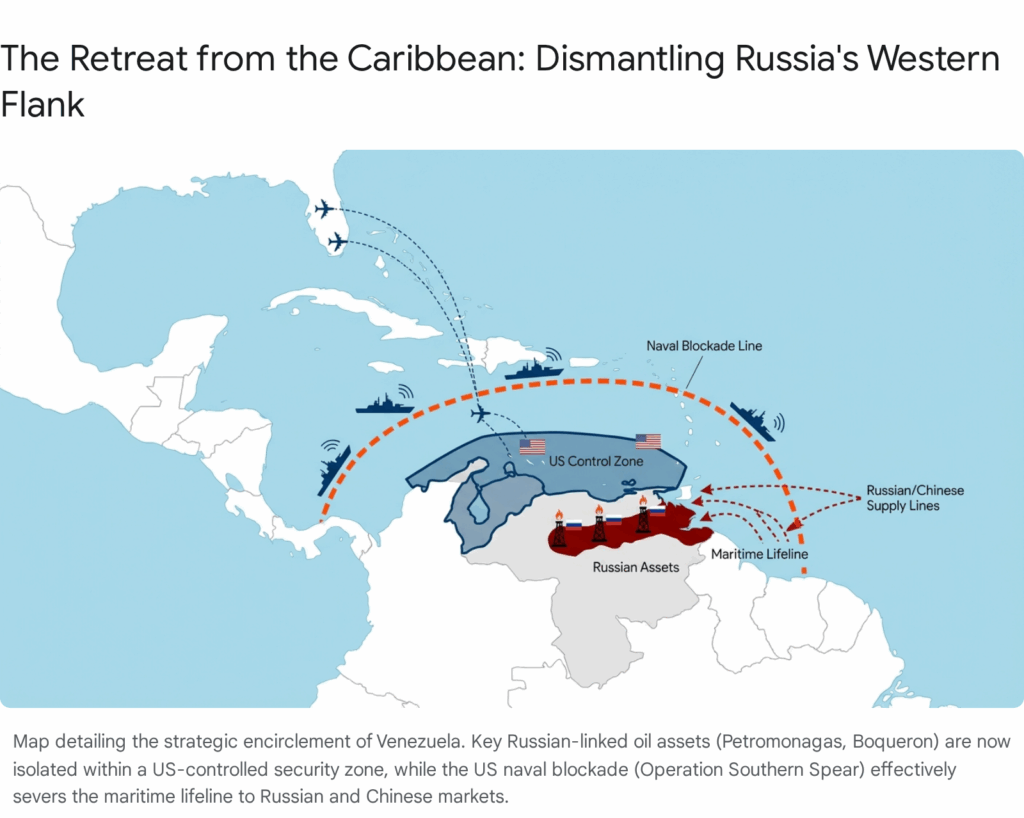

Furthermore, the operational precedent set by the US naval blockade and the pursuit of the Russian-reflagged tanker Marinera signals a new, aggressive interpretation of maritime law that endangers Russia’s “shadow fleet” globally.11 This report provides an exhaustive analysis of these impacts, mapping the chain of consequences from the loss of the Caribbean bridgehead to the fiscal shocks in Moscow and the likely asymmetric responses available to the Kremlin.

I. The Geopolitical Shockwave: The Revival of the “Don-roe” Doctrine

The extraction of Nicolás Maduro by US forces marks the most significant reassertion of American hard power in the Western Hemisphere since the Cold War era. For Moscow, this intervention is not a peripheral loss but a direct assault on its strategy of “reciprocal pressure.” Since the early 2000s, and accelerating under Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro, Russia has utilized Venezuela as a symmetric counter-weight to US influence in Ukraine and Eastern Europe. The logic was explicit: if Washington could expand NATO into Russia’s “near abroad,” Moscow would cultivate a military and economic foothold in Washington’s “backyard”.4 The sudden and total removal of this lever forces a recalibration of Kremlin foreign policy.

The Collapse of the Forward Operating Base

The speed of Operation Absolute Resolve has inflicted severe reputational and operational damage on the Russian Federation. Moscow had invested heavily in the survival of the Chavista regime, deploying military advisors, S-300 air defense systems, and reportedly Wagner Group personnel to Venezuela to provide regime security.3 These assets were intended to serve as a tripwire against US intervention. Their failure to detect, deter, or repel the US operation exposes a critical weakness in Russian power projection capabilities.

The operational reality revealed by the January 2026 intervention is that Russia lacks the logistical capacity to sustain a high-intensity defense of its allies across the Atlantic while fully committed to the war in Ukraine. Russian military analysts have noted with alarm that the US operation was executed with a speed and decisiveness that contrasts sharply with the protracted nature of Russia’s own “Special Military Operation”.14 This failure resonates beyond Caracas. Client states relying on Russian security guarantees—from Syria to the Sahel—are witnessing a stark demonstration of Moscow’s limitations when confronted by direct US military resolve. The “invincibility” of Russian-backed authoritarian survival strategies has been pierced, potentially encouraging opposition movements in other Russian client states to test the Kremlin’s resolve.

The “Wild West” Precedent and Spheres of Influence

While the loss is acute, Russian strategists are attempting to salvage a diplomatic narrative from the wreckage. By framing the US intervention as a return to 19th-century imperialism—dubbed the “Don-roe Doctrine” by some analysts, a play on the Monroe Doctrine 15—Moscow aims to solidify its own claims to a sphere of influence in Eastern Europe. The Kremlin’s diplomatic messaging has focused on the “illegality” of the US action, arguing that if Washington can claim exclusive rights to manage political outcomes in the Americas, Russia has an identical right to dictate the political future of Ukraine and Belarus.4

However, this rhetorical pivot conceals a grim reality: the global order is shifting toward a raw transactionalist model where “might makes right.” While Russia has long championed this shift away from a rules-based order, it is now on the losing end of the equation in the Caribbean. The Kremlin’s silence and lack of substantive military counter-moves suggest a tacit acknowledgement that it cannot contest the US in the Western Hemisphere.16 The “strategic partnership” signed between Putin and Maduro in May 2025 has been rendered null and void, proving that diplomatic paper is worthless without the force projection to back it.5

II. The Energy War: Displacement of the Urals Blend

The most tangible and damaging impact on Russia will manifest in the global oil markets. The Russian war economy is predicated on the export of medium-sour Urals crude, primarily to India and China, often at a discount to Brent but above the Western price cap. The reentry of Venezuelan heavy crude into the open market, under US administration, poses a direct threat to this market share.

Crude Quality Competition: Heavy vs. Medium Sour

Venezuela possesses the world’s largest proven oil reserves, primarily heavy and extra-heavy crude in the Orinoco Belt.18 Historically, this oil was the ideal feedstock for complex refineries in the US Gulf Coast (USGC), which were specifically engaged to process heavy, high-sulfur barrels.8 Following the imposition of sanctions, this oil was diverted to China, where it competed directly with Russian Urals and Iranian heavy grades for market share among independent “teapot” refiners.9

With the US now controlling the flow, two scenarios emerge, both detrimental to Russia:

- The Repatriation of Barrels: The US administration has signaled an intent to direct Venezuelan output back to Gulf Coast refineries to lower domestic gasoline prices and fuel “reindustrialization”.8 This repatriation of barrels accomplishes a strategic dual purpose for the US: it lowers domestic energy costs and, critically, it removes Venezuelan supply from the “dark market.” Every barrel of Venezuelan crude that returns to the USGC is a barrel that is no longer available to Chinese independent refiners at a deep discount. This forces Chinese buyers to look elsewhere, potentially to Russia, but without the leverage of a cheap Venezuelan alternative, or conversely, it forces Russia to compete more aggressively against Iranian barrels for the remaining “dark” market share.

- The Asian Displacement: If production is ramped up significantly—Goldman Sachs estimates a potential, though slow, recovery 10—and sanctions are lifted for compliant buyers, Venezuelan oil becomes a legitimate alternative for India and China. Indian refiners, such as Reliance Industries, have historically been significant buyers of Venezuelan crude. They have struggled with payment mechanisms for Russian oil due to sanctions and currency risks.9 If US-controlled Venezuela offers a stable, legal supply of heavy crude, Indian refiners may prefer it over sanctioned Russian barrels, which carry the constant risk of secondary sanctions and logistical disruption.

The “Price Cap” Evasion Squeeze and Revenue Erosion

Russia’s ability to fund its war in Ukraine relies on the “shadow fleet” and the willingness of Asian buyers to skirt Western sanctions to buy oil. If Venezuela returns to the fold of the global energy market, it introduces a massive volume of “legitimate” heavy crude. This increases the supply elasticity for buyers like China and India.

According to market analysis, even a modest increase in Venezuelan output to 2 million barrels per day (bpd) could depress long-term oil prices by approximately $4 per barrel.10 For Russia, which operates on thin margins due to the high cost of transport, insurance, and the “war risk” premiums attached to its sanctioned oil, a $4 drop is magnified. Furthermore, to compete with legitimate Venezuelan barrels that carry no sanctions risk, Russia would be forced to offer even steeper discounts to Chinese and Indian buyers. This dynamic erodes the net revenue entering the Kremlin’s coffers, directly impacting the fiscal stability of the Russian state.9 The discount on Urals crude, which Russia has fought to narrow, would likely widen again as buyers gain leverage.

III. Next Steps for the Venezuelan Oil Industry: A Challenge to Russian Interests

The immediate post-intervention phase for the Venezuelan oil industry will be defined by a US-led reconstruction effort that systematically excludes Russian participation. The path to recovery for PDVSA (Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A.) is fraught with technical and financial challenges, but the direction of travel—toward Western integration—is unambiguous.

Assessment of Infrastructure Decay

The Venezuelan oil sector has suffered from a decade of catastrophic underinvestment, brain drain, and looting. Production capacity has collapsed from over 3 million bpd in the late 1990s to approximately 800,000–900,000 bpd at the time of the intervention.18 The physical infrastructure—pipelines, pumping stations, and the critical “upgraders” in the Orinoco Belt that convert extra-heavy crude into exportable blends—is in a state of advanced disrepair.20

Reports indicate that looting of equipment has been widespread, and the “asset specificity” of the heavy oil infrastructure means that simply throwing money at the problem will not yield immediate results. Restoring production to 2 million bpd is estimated to require tens of billions of dollars and several years of sustained effort.2 However, unlike the Maduro regime, the US administration can leverage the technical expertise and capital of US supermajors.

The Return of the US Majors

The US strategy is explicitly reliant on private enterprise to fund the reconstruction. President Trump has stated that US oil companies will “go in, spend billions of dollars, fix the badly broken infrastructure… and start making money for the country”.20 This points to a rapid return of companies like Chevron, ConocoPhillips, and ExxonMobil, many of whom have outstanding arbitration claims against Venezuela for past expropriations.

- Chevron: Already operating under a special license, Chevron is best positioned to lead the immediate stabilization of output.26

- ConocoPhillips and Exxon: These companies, which left Venezuela under Chávez, may return under a new legal framework that swaps their debt claims for equity in new Joint Ventures.2

This “debt-for-equity” model is particularly dangerous for Russia. As US companies swap their arbitration awards for control of oil fields, they will likely displace existing operators—including Russian entities—whose contracts may be deemed illegitimate by the new administration.

Production Ramp-Up Scenarios

Analysts are divided on the speed of the recovery, but even a slow ramp-up impacts Russia.

- Short Term (0-12 months): Production is likely to remain flat or dip slightly as the chaos of the transition settles and the US assesses the state of the facilities. The immediate focus will be on stabilizing the power grid and stopping the decline.29

- Medium Term (1-3 years): With US capital and security, production could rise by 500,000 to 1 million bpd. JPMorgan analysts see a potential rise to 1.3–1.4 million bpd in two years.21

- Long Term (3+ years): A return to 2.5–3 million bpd is possible but would require sustained political stability and investment exceeding $80 billion.2

OPEC+ Implications

Venezuela is a founding member of OPEC. Under US control, its relationship with the cartel—and specifically with the OPEC+ format led jointly by Saudi Arabia and Russia—becomes highly uncertain.

- Quota Non-Compliance: A US-administered Venezuela is unlikely to adhere to OPEC+ production quotas designed to prop up oil prices. The US priority will be volume maximization to repay debts and lower global prices, directly undermining Russia’s efforts to restrict supply.2

- Fracture of the Alliance: If Venezuela exits OPEC or simply ignores its mandates, it weakens the cartel’s cohesion. Russia relies on OPEC+ coordination to maintain the price floor for oil; a rogue producer with massive reserves under US tutelage disrupts this mechanism.

IV. Financial Exposure: The Roszarubezhneft Debacle

The financial linkage between Moscow and Caracas is deep, structural, and now largely toxic. Following the imposition of US sanctions on Rosneft in 2020, the Russian state created Roszarubezhneft, a 100% state-owned entity, to absorb Rosneft’s Venezuelan assets.6 This transfer was designed to protect the publicly traded Rosneft from sanctions, but it effectively concentrated the risk directly onto the Russian state balance sheet.

Asset Expropriation and “Odious Debt”

With the US vowing to “run” Venezuela and rebuild its infrastructure using US oil majors 20, the legal status of Roszarubezhneft’s Joint Ventures (JVs) is in extreme jeopardy. The new US-backed administration is likely to declare contracts signed under the Maduro regime as invalid or subject to renegotiation under terms unfavorable to Moscow.

- The Debt Stack: Venezuela owes billions to Russia, consisting of sovereign debt and pre-payments for oil that was never delivered.31 Russian state media has estimated the value of stakes in ventures like Petromonagas, Petroperija, and Boqueron at around $5 billion.31

- The Collateral Trap: Rosneft (now Roszarubezhneft) historically held liens on Venezuelan oil cargos and assets (such as the 49.9% stake in CITGO, though this has been the subject of complex litigation).33 With the US blockading exports and controlling the fields, there is no physical way for Russia to collect on these debts via oil shipments.24

- Legal Warfare: The US administration has signaled that US oil companies must invest to rebuild the sector before they can recoup their own lost assets.28 In this queue of creditors, Russian state entities will undoubtedly be placed last. Legal scholars anticipate the US may designate Russian loans as “odious debt”—debt incurred by a despotic regime for purposes that did not serve the population—thereby nullifying Russia’s claims entirely.32

The loss of these assets is not just a paper loss; it is a destruction of capital that was intended to serve as a long-term strategic reserve and revenue stream for the Russian state.

V. The “Shadow Fleet” Crisis and Maritime Precedents

Perhaps the most dangerous development for Russia is not taking place on Venezuelan soil, but in the international waters surrounding it. The US pursuit and potential seizure of the tanker Marinera (formerly Bella 1) sets a legal and operational precedent that strikes at the heart of Russia’s ability to export oil globally.11

The Flag-State Immunity Challenge

The Bella 1, a known dark fleet tanker, attempted to evade US interdiction by re-flagging to Russia and renaming itself Marinera mid-voyage.36 Typically, a vessel flying a national flag is considered sovereign territory, and boarding it without the flag state’s consent is a violation of international law. However, the US has proceeded with the pursuit, treating the re-flagging as a fraudulent attempt to evade law enforcement rather than a legitimate sovereign act. US officials have argued that because the vessel was “stateless” or flying a false flag at the time the pursuit began, it does not enjoy retroactive protection from the Russian flag.37

If the US successfully seizes a vessel flying the Russian flag—arguing it is “stateless” due to fraudulent registration or engaged in “criminal” activity (narco-terrorism support via Maduro)—it creates a devastating precedent for Moscow.

- Implication: The US could theoretically apply this legal logic to any vessel in Russia’s shadow fleet carrying oil above the price cap. If a vessel is deemed to be using deceptive practices (AIS spoofing, false documents), the US could argue it forfeits sovereign immunity.

- Russian Reaction: Moscow has already filed diplomatic protests, viewing this as a test case.38 If they fail to protect the Marinera, the perceived security of the entire Russian shadow fleet will collapse. Insurance premiums for these vessels will skyrocket, and shipowners may refuse to carry Russian cargo if they believe US naval interdiction is a genuine risk.36

The Naval Blockade (Operation Southern Spear)

The implementation of a naval blockade (“quarantine”) on Venezuelan oil 39 demonstrates a US willingness to physically interdict energy flows. For Russia, which relies on narrow maritime chokepoints like the Danish Straits and the Bosporus for its oil exports, the normalization of naval blockades against major oil producers is an existential threat. It signals that the “freedom of navigation” for energy carriers is no longer guaranteed for US adversaries. The “quarantine” concept, famously used during the Cuban Missile Crisis, allows the US to filter traffic based on cargo content, effectively strangling a regime’s economic lifeline without declaring a formal war on the shipping nations.

VI. Second-Order Effects: The China Pivot and Eurasian Unity

The US control of Venezuela forces a difficult choice upon the People’s Republic of China, driving a potential wedge in the Sino-Russian “No Limits” partnership.

China’s Energy Pragmatism

China is the world’s largest importer of oil and has been the primary buyer of sanctioned Venezuelan crude, importing roughly 430,000 bpd in 2025.41 With the US now controlling the spigot, Beijing faces a stark dilemma:

- Confrontation: Continue buying “black market” Venezuelan oil (if any can slip the blockade) and risk secondary sanctions, naval interdiction, and a trade war with the US.

- Compliance: Accept US control, negotiate with the new administration for legitimate access to Venezuelan oil, and diversify away from “risky” suppliers.9

Evidence suggests China is pragmatic. Chinese refiners have already paused purchases of Venezuelan crude to assess the new reality, fearing US seizures.42 If the US successfully rehabilitates the Venezuelan oil sector and allows exports to China (to stabilize global prices and ensure Chinese neutrality), Beijing may reduce its reliance on Russian Urals. This would reduce Russia’s leverage over its most important economic partner. Russia needs China more than China needs Russia; if Venezuela offers a stable, high-quality heavy crude alternative, the “discount” Russia must offer to Beijing will deepen to maintain market share.18

The Fracture of the “Revisionist Bloc”

Venezuela was a key node in the “Axis of Resistance” (Russia, Iran, Venezuela, Cuba). The fall of Maduro isolates Cuba, which relied on Venezuelan oil subsidies for its economic survival.32 The likely economic collapse of Cuba would force Russia to either subsidize the island nation at a massive cost—something the strained Russian budget can ill afford—or watch another ally fall to US pressure. Furthermore, the perception that Russia could not save Maduro may lead other partners (Iran, North Korea) to question the value of Russian security assurances. They may prioritize their own nuclear deterrence over reliance on Russian diplomatic or conventional military support, leading to a more volatile and less coordinated anti-Western bloc.

VII. Russia’s Asymmetric Response Options

Cornered in the Caribbean and squeezed in the energy markets, Russia lacks the conventional projection capacity to reverse the situation in Venezuela. Direct military intervention is logistically impossible given the distance and the ongoing commitment in Ukraine.43 Therefore, Moscow’s response will be asymmetric, designed to inflict pain on US interests elsewhere and re-establish deterrence.

1. Escalation in Ukraine

The most likely venue for retaliation is Ukraine. Viewing the loss of Venezuela as a US escalation of the global conflict, the Kremlin may justify “total war” tactics in Ukraine. This could involve targeting energy infrastructure, leadership nodes, or logistics hubs with renewed intensity, mirroring the US “decapitation” of the Maduro regime.3 The logic of “reciprocal damage” suggests that if the US can topple a Russian ally, Russia must destroy a US ally.

2. The “Grey Zone” Maritime Campaign

Russia may intensify “grey zone” warfare at sea to challenge the US naval dominance asserted in the Caribbean. This could include:

- Cable Cutting: Sabotage of undersea data cables in the Atlantic, claiming “unknown actors” are responsible, as a warning shot regarding US naval dominance and economic stability.

- Shadow Fleet Harassment: Retaliatory harassment of Western commercial shipping in the Black Sea or Red Sea (via Houthi proxies), citing the Marinera precedent to justify boarding operations. If the US can board Russian-flagged ships, Russia may argue it can board Western-flagged ships suspected of carrying “contraband” for Ukraine.45

3. Cyber and Hybrid Warfare

The US plan to “run” Venezuela relies on the stability of the interim government and the physical security of the oil infrastructure. Russia retains significant cyber capabilities and human intelligence networks within Venezuela.13 We can expect a sustained campaign of sabotage, disinformation, and cyber-attacks aimed at the new Venezuelan administration and the US oil companies attempting to operate there. The goal will be to make Venezuela ungovernable and the oil unrecoverable, thereby denying the US the fruits of its victory and keeping global oil prices high.

Conclusion

The US assumption of control over Venezuelan oil is a watershed moment that significantly degrades the Russian Federation’s global standing. It strips Moscow of its most important asset in the Western Hemisphere, threatens the financial solvency of its state-owned energy vehicles, and introduces a potent competitor to its oil exports in critical Asian markets.

While the Kremlin projects an image of defiant silence, the strategic reality is one of containment. The “Don-roe Doctrine” has effectively closed the Caribbean to Russian power projection. Russia’s response will likely be defined by increased brutality in its near abroad (Ukraine) and disruptive hybrid warfare globally, but the loss of the Venezuelan bridgehead is irreversible. The era of Russia acting as a global spoiler in the Americas has, for the immediate future, been brought to a close by the realities of energy economics and American naval power.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- 2026 United States strikes in Venezuela – Wikipedia, accessed January 6, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2026_United_States_strikes_in_Venezuela

- Q&A on US Actions in Venezuela – Center on Global Energy Policy, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/qa-on-us-actions-in-venezuela/

- The Fall of Maduro: How Russia Lost an Ally but Gained a Like-Minded Thinker, accessed January 6, 2026, https://ridl.io/russia-has-no-allies/

- Analysis: Russia Loses Ally in Venezuela, Sees Opportunity in Trump’s ‘Wild West’ Realpolitik, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.kyivpost.com/analysis/67523

- Russia loses ally in Venezuela but hopes to gain from Trump’s ‘Wild West’ realpolitik, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.cnbcafrica.com/2026/russia-loses-ally-in-venezuela-but-hopes-to-gain-from-trumps-wild-west-realpolitik

- Venezuela Approves 15-Year Extension of Russia-Linked Oil Joint Ventures, accessed January 6, 2026, https://energynow.com/2025/11/venezuela-approves-15-year-extension-of-russia-linked-oil-joint-ventures/

- Rosneft’s Withdrawal amid U.S. Sanctions Contributes to Venezuela’s Isolation – CSIS, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.csis.org/analysis/rosnefts-withdrawal-amid-us-sanctions-contributes-venezuelas-isolation

- Dense, sticky and heavy: why Venezuelan crude oil appeals to US refineries, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2026/jan/05/venezuelan-crude-oil-appeals-to-us-refineries

- TSG MARKET INSIGHTS | Venezuela, Russia, and the Oil Balance – The Signal Group, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.thesignalgroup.com/newsroom/market-insights-venezuela-russia-and-the-oil-balance

- Goldman Sachs sees bearish long-term oil risk after Venezuela | Seeking Alpha, accessed January 6, 2026, https://seekingalpha.com/news/4536508-goldman-sachs-sees-bearish-long-term-oil-risk-after-venezuela

- Tanker Evading Venezuela Blockade Paints Russian Flag as U.S. Pursuit Continues, accessed January 6, 2026, https://windward.ai/blog/tanker-evading-venezuela-blockade-paints-russian-flag-as-u-s-pursuit-continues/

- Report: U.S. Still Plans to Seize Fleeing Russian-Flagged Tanker – The Maritime Executive, accessed January 6, 2026, https://maritime-executive.com/article/report-u-s-still-plans-to-seize-fleeing-russian-flagged-tanker

- With Maduro Gone, Putin Risks Being Pushed Out of the Western Hemisphere, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2026/01/05/with-maduro-gone-putin-risks-being-pushed-out-of-the-western-hemisphere-a91608

- From grudging respect to unease: Russia weighs up fall of Maduro, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/05/russia-weighs-up-fall-of-nicolas-maduro-venezuela

- Making sense of the US military operation in Venezuela, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/making-sense-of-the-us-military-operation-in-venezuela/

- Decapitation Strategy in Caracas: The Logic, Timing, and Consequences of the U.S. Operation in Venezuela, accessed January 6, 2026, https://lansinginstitute.org/2026/01/03/decapitation-strategy-in-caracas-the-logic-timing-and-consequences-of-the-u-s-operation-in-venezuela/

- The ‘Putinization’ of US foreign policy has arrived in Venezuela – The Guardian, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/03/putin-russia-us-foreign-policy-venezuela

- Venezuelan Political Transition Reshapes Global Oil Market Dynamics – Discovery Alert, accessed January 6, 2026, https://discoveryalert.com.au/venezuelan-political-transition-oil-dynamics-2026/

- Trump move to cap oil, Venezuela output in focus, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.nationthailand.com/news/world/40060760

- Trump suggests US taxpayers could reimburse oil firms for Venezuela investment, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2026/jan/06/trump-us-taxpayers-oil-firms-venezuela-investment

- Analysts predict that Venezuelan oil production will increase in the future and lower prices., accessed January 6, 2026, https://energynews.oedigital.com/oil-gas/2026/01/05/analysts-predict-that-venezuelan-oil-production-will-increase-in-the-future-and-lower-prices

- How Venezuelan oil factored into the US capture of Maduro, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.straitstimes.com/business/companies-markets/how-venezuelan-oil-factored-into-the-us-seizure-of-maduro

- Venezuela’s oil supply to rise in years ahead and depress prices, say analysts, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.cnbcafrica.com/2026/venezuelas-oil-supply-to-rise-in-years-ahead-and-depress-prices-say-analysts

- U.S. Oil Companies Face Significant Costs and Risks When Reentering Venezuela, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.asisonline.org/security-management-magazine/latest-news/today-in-security/2026/january/oil-companies-venezuela/

- Reviving Venezuela’s oil industry no easy feat: Update | Latest Market News – Argus Media, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.argusmedia.com/en/news-and-insights/latest-market-news/2772065-reviving-venezuela-s-oil-industry-no-easy-feat-update

- The Commodities Feed: Venezuelan and Russian oil supply risks …, accessed January 6, 2026, https://think.ing.com/articles/the-commodities-feed-venezuelan-and-russian-oil-supply-risks-push-the-market-higher181225/

- Houston oil companies react as Venezuela turmoil raises questions about energy markets, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.click2houston.com/news/local/2026/01/05/houston-oil-companies-react-as-venezuela-turmoil-raises-questions-about-energy-markets/

- U.S. pushes oil majors to invest big in Venezuela – Denver Gazette, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.denvergazette.com/2026/01/05/u-s-pushes-oil-majors-to-invest-big-in-venezuela/

- Goldman Sachs sees limited Venezuela oil recovery after U.S. action | Seeking Alpha, accessed January 6, 2026, https://seekingalpha.com/news/4536507-goldman-sachs-sees-limited-venezuela-oil-recovery-after-u-s-action

- Opec+ opts for caution as US takeover of Venezuela oil adds supply risks – The National News, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.thenationalnews.com/business/energy/2026/01/04/opec-opts-for-caution-as-us-takeover-of-venezuela-oil-adds-supply-risks/

- Factbox-What’s the status of international oil companies in Venezuela after Maduro’s capture? By Reuters – Investing.com, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.investing.com/news/commodities-news/factboxwhats-the-status-of-international-oil-companies-in-venezuela-after-maduros-capture-4430480

- Venezuela’s billions in distressed debt: Who is in line to collect?, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.foxbusiness.com/economy/venezuelas-billions-distressed-debt-who-line-collect

- 22 USC 9752: Concerns over PDVSA transactions with Rosneft – OLRC Home, accessed January 6, 2026, https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml;jsessionid=220ADD9E32B4922036C309D0C259AEDD?path=&req=granuleid%3AUSC-prelim-title22-section9752&f=&fq=&num=0&hl=false&edition=prelim

- Trump’s attack leaves China worried about its interests in Venezuela, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/05/venezuela-trump-attack-china-interests-analysis

- Treasury Targets Oil Traders Engaged in Sanctions Evasion for Maduro Regime, accessed January 6, 2026, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sb0348

- Sanctioned Oil Tanker – Bella 1 – SOF News, accessed January 6, 2026, https://sof.news/news/bella-1-oil-tanker/

- Tanker chased by US Coast Guard gains Russian flag and new name – NYT, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.pravda.com.ua/eng/news/2026/01/01/8014213/

- Russia files diplomatic request asking U.S. to stop pursuing oil tanker originally bound for Venezuela, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.ctvnews.ca/world/article/russia-files-diplomatic-request-asking-us-to-stop-pursuing-oil-tanker-originally-bound-for-venezuela/

- United States oil blockade during Operation Southern Spear – Wikipedia, accessed January 6, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_oil_blockade_during_Operation_Southern_Spear

- Venezuela on Notice: What Comes Next for Dark Fleet Enforcement, accessed January 6, 2026, https://windward.ai/blog/venezuela-on-notice-what-comes-next-for-dark-fleet-enforcement/

- China demands ‘immediate release’ of Venezuela’s Maduro | Latest Market News, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.argusmedia.com/en/news-and-insights/latest-market-news/2771768-china-demands-immediate-release-of-venezuela-s-maduro

- Chinese refiners seek alternatives to Venezuelan crude, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.argusmedia.com/en/news-and-insights/latest-market-news/2771875-chinese-refiners-seek-alternatives-to-venezuelan-crude

- Why Russia Intervening in a U.S.-Venezuela War Is Plausible, But It’s a Bad Idea – YouTube, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s0lPlgjfOP8

- Russia Demands Release of Maduro After U.S. Military Strikes Venezuela, accessed January 6, 2026, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2026/01/03/russia-demands-release-of-maduro-after-us-military-strikes-venezuela-a91602

- US plans to intercept Venezuela-linked oil tanker claimed by Russia – Al Mayadeen English, accessed January 6, 2026, https://english.almayadeen.net/news/politics/us-plans-to-intercept-venezuela-linked-oil-tanker-claimed-by