The Tourism and Antiquities Police (TAP) of the Arab Republic of Egypt represents a critical instrument of state power, serving a dual function essential to national stability and economic survival. Its primary mission is the physical protection of the multi-billion-dollar tourism industry, a foundational pillar of the Egyptian economy. Concurrently, it serves a vital political purpose: projecting an image of absolute state control and enduring stability, a narrative central to the legitimacy of the current government under President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. The TAP is not merely a specialized law enforcement branch; it is a key component of Egypt’s national security apparatus.

This report assesses that the TAP has evolved into a highly visible, para-militarized force whose doctrine and operational posture have been overwhelmingly shaped by two seminal events: the traumatic 1997 Luxor Massacre and the systemic collapse of state authority during the 2011 Revolution. The force’s effectiveness is consequently bifurcated. It demonstrates a high degree of success in deterring and preventing large-scale, coordinated terrorist attacks against high-profile tourist destinations in major urban centers like Cairo and Alexandria. This is achieved through a doctrine of overwhelming, visible security presence and hardened site defenses. However, this same model proves vulnerable to attacks by lone actors or small cells, as recent incidents in Alexandria have demonstrated. Furthermore, the force remains largely ineffective at stemming the systemic, low-level looting and illegal excavation of countless remote antiquities sites, a persistent drain on the nation’s cultural heritage.

A key judgment of this analysis is the existence of persistent friction and critical coordination failures between the Ministry of Interior (MOI), under which the TAP operates, and the Egyptian Armed Forces (EAF). This institutional seam creates significant operational risks, particularly in remote areas where jurisdictions overlap, as tragically demonstrated by the 2015 friendly fire incident in the Western Desert. The future challenges for the TAP will be defined by the need to adapt its security posture to counter evolving threats—shifting from large, organized groups to ideologically motivated lone actors—and to manage the inherent tension between providing robust security and avoiding the perception of an oppressive police state that could itself deter international visitors.

II. Historical Precedent: From the Medjay to the Modern Ministry

The existence of a specialized security force dedicated to protecting Egypt’s cultural and economic assets is not a modern phenomenon but a deeply rooted tradition of the Egyptian state. Understanding this historical context is crucial to appreciating the contemporary importance placed upon the Tourism and Antiquities Police. The concept of linking national security directly to the safeguarding of heritage is a foundational element of Egyptian statecraft.

The Pharaonic Legacy

The direct precursors to the modern TAP can be traced back thousands of years to the Pharaonic era, most notably to the elite units of the New Kingdom (c. 1570-1069 BCE) known as the Medjay.1 Originally a nomadic people from Nubia, the Medjay were first integrated into the Egyptian state as desert scouts and mercenaries during the Middle Kingdom (c. 2040–1782 BCE).2 Renowned for their loyalty, combat prowess, and knowledge of the desert, they evolved into an elite, multicultural paramilitary police force entrusted with the state’s most sensitive security tasks.1

The Medjay’s mandate was remarkably similar to that of the modern TAP. They were the primary guardians of high-value sites, including the royal necropolises in the Valley of the Kings, temples that served as religious and economic centers, and state treasuries.2 They also patrolled critical trade routes and protected caravans carrying gold and other precious goods.4 Beyond static guarding, the Medjay performed investigative duties. The detailed records of the Ramesside Tomb Robbery Trials (c. 1100 BCE) reveal their role in interrogating suspects, gathering evidence, and bringing criminals before the courts, where they also served as bailiffs.1 This ancient force operated within a clear command structure, with the Chief of the Medjay being appointed by and accountable to the Vizier, the pharaoh’s highest official, ensuring that law enforcement was aligned with state policy.1 This historical precedent establishes that the protection of heritage and its associated economic assets has been considered a core function of the central government in Egypt for millennia.

Formation of the Modern Police Apparatus

Following the Pharaonic period, law enforcement systems continued to evolve through the Greco-Roman, Islamic, and Ottoman eras, often with localized or military-led structures.5 The foundation of the modern Egyptian police, however, was laid in the 19th century. Mohamed Ali Pasha began to regulate and formalize a police system, creating specialized departments such as customs and secret police.6 The institutional structure we recognize today truly began to take shape under Khedive Ismail, who in 1863 brought in European officers to help organize the force and first officially introduced the word “police” into the Egyptian government lexicon.6

This period of formation is significant because it embedded within the Egyptian police an institutional culture derived from its colonial-era context. The police were established not just as a civil service to protect the public, but as a centralized, militarized tool for social control, intelligence gathering, and the protection of the ruling regime.8 This dual role—serving the public and serving the state’s political interests—has remained a defining characteristic of the Egyptian police apparatus to the present day.

Codification of the Modern Mandate

In the 20th century, as tourism became an increasingly vital component of the national economy, the need for a specialized security body became apparent. A key turning point was the government’s Five Year Plan of 1976, which formally recognized tourism as a central economic pillar and allocated significant state funds to its development.10 This economic prioritization directly led to the creation of the

General Administration of Tourism and Antiquities Police as a specialized directorate within the Ministry of Interior.10

The legal foundation for the “Antiquities” component of the TAP’s mission was solidified with the passage of Law No. 117 of 1983 on Antiquities Protection.11 This landmark legislation established all antiquities as the property of the state, completely abolished the licensed trade and export of artifacts, and instituted harsh penalties for theft and smuggling.11 The law provided the TAP with the unambiguous legal authority to pursue antiquities trafficking as a serious crime against the state. This law was subsequently strengthened by amendments in 2010 (Law No. 3 of 2010), which increased penalties and further criminalized the trade.12 The combination of the force’s creation and this robust legal framework cemented the state’s doctrine that protecting heritage is a matter of national security, directly linking the actions of the TAP to the economic health and international prestige of Egypt.

III. The Modern Force: Structure, Mandate, and Doctrine

The contemporary Tourism and Antiquities Police is a formidable and highly specialized component of Egypt’s internal security architecture. Its structure, mandate, and training reflect the state’s prioritization of the tourism sector and the high-threat environment in which it operates.

Organizational Placement

The TAP is a directorate operating under the authority of the Deputy Minister for Special Police, one of four such deputies within the powerful Ministry of Interior.7 This organizational placement is significant, situating the TAP alongside other key national security units like the Central Security Forces (CSF), the Traffic Police, and the Presidential Police. It is not a minor or ancillary unit but a core part of the “Special Police” apparatus. The force is deployed nationally, with its command structure mirroring the country’s administrative divisions into 27 governorates. Each governorate with a significant tourism or antiquities presence, such as Cairo, Giza, Alexandria, Luxor, and Aswan, maintains its own TAP directorate responsible for all related police operations within its jurisdiction.7

Official Mandate

The official mandate of the General Administration of Tourism and Antiquities Police is comprehensive, extending beyond simple guard duties to encompass a wide range of security, law enforcement, and regulatory functions.10 Its duties can be broken down into four primary areas:

- Physical Security: This is the most visible aspect of its mission. It includes the protection of tourists at hotels, on Nile cruises, and during transit between locations. It also involves securing the physical infrastructure of archaeological sites, museums, and other cultural facilities against threats of terrorism, vandalism, or public disorder.10

- Antiquities Protection: The TAP is the lead law enforcement agency for combating the illegal trade in antiquities. This involves preventing theft from museums and registered sites, investigating and disrupting smuggling networks, and interdicting stolen artifacts. To this end, the TAP works with the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities to staff specialized units at all of Egypt’s airports, seaports, and land border crossings to inspect suspicious items and prevent their illegal export.11

- Law Enforcement and Investigation: The force is responsible for investigating all crimes committed against tourists, ranging from petty theft and scams to more serious assaults. Officers are tasked with handling tourist complaints and providing assistance to foreign nationals who are victims of crime.10

- Regulatory Oversight: The TAP has a regulatory function, overseeing tourism companies, hotels, and tourist-oriented shops to ensure they are operating in compliance with government regulations and licensing requirements.10 This includes addressing cases of trespassing on archaeological lands.10

This broad mandate creates an inherent doctrinal tension. TAP officers are required to function simultaneously as a welcoming, helpful presence for tourists and as a hardened, intimidating security force to deter terrorists and criminals. They must project an image of safety and accessibility while maintaining a high level of operational readiness and suspicion. This balancing act between the roles of “host” and “guardian” is a constant challenge for the force’s leadership and training programs, as an overemphasis on one role can critically undermine the other. An overly aggressive security posture can damage the tourist experience and harm the economy, while a lax approach invites attack. This dilemma shapes every tactical decision made on the ground, from the intensity of a checkpoint search to the proximity of an armed escort.

Recruitment and Training

All commissioned officers in the Egyptian National Police, including those who will serve in the TAP, are graduates of the National Police Academy in Cairo.7 The academy is a modern, university-level institution that offers a four-year program for high school graduates, culminating in a bachelor’s degree in police studies.15 The curriculum is extensive and has a distinct para-militarized character from its inception.8 Cadets receive training in security administration, criminal investigation, military drills, marksmanship, and counter-terrorism tactics alongside academic subjects like forensic medicine, sociology, and foreign languages (primarily English and French).7

This foundational training instills a military-style discipline and command structure common to all branches of the Egyptian police. Upon graduation, officers selected for the TAP would receive further specialized training relevant to their unique mission. This would include courses on cultural property law, protocols for interacting with foreign nationals, dignitary protection techniques, and site-specific security procedures for major archaeological zones. Some officers, particularly those in special operations or counter-terrorism roles, may also receive advanced training from the Egyptian Armed Forces at facilities like the Al-Sa’ka Military School.7

IV. Trial by Fire: The Luxor Massacre and the Securitization of Tourism

While the TAP existed prior to 1997, its modern form, doctrine, and operational posture were forged in the crucible of one of the most brutal terrorist attacks in Egypt’s history. The Luxor Massacre was a strategic shock that fundamentally and permanently altered the state’s approach to tourism security, transforming the TAP from a specialized police unit into a heavily armed, front-line force in the war on terror.

The 1990s Islamist Insurgency as a Prelude

The 1997 attack did not occur in a vacuum. Throughout the early and mid-1990s, Egypt was embroiled in a low-level insurgency waged by Islamist militant groups, principally al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya (the Islamic Group).16 A key tactic of these groups was to target the tourism sector, correctly identifying it as a vital artery of the Egyptian economy and a symbol of the secular Mubarak government’s ties to the West.17 This period saw a string of attacks on tourist buses and Nile cruise ships, particularly in southern Egypt, which served as a grim prelude to the events at Luxor.16

Case Study: The 1997 Luxor Massacre

On the morning of November 17, 1997, six militants from al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya, disguised as members of the security forces, launched a coordinated assault on the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri, one of Luxor’s most iconic archaeological sites.16 The attack was executed with chilling precision and brutality. After killing the two armed security guards at the entrance, the attackers systematically moved through the temple’s terraces for 45 minutes, trapping tourists and shooting them with automatic firearms before mutilating many of the bodies with knives and machetes.16

In total, 62 people were killed: 58 foreign tourists (including Swiss, Japanese, German, and British nationals) and 4 Egyptians.16 Among the Egyptian dead were three police officers and a tour guide who were caught in the assault.21 The attackers left behind leaflets demanding the release of Sheikh Omar Abdel-Rahman, the group’s spiritual leader imprisoned in the United States.20 After the massacre, the terrorists hijacked a bus but were intercepted by a checkpoint of Egyptian police and military forces. Following a shootout, the attackers fled into the nearby hills, where their bodies were later found in a cave, having apparently committed suicide.20

The attack exposed catastrophic failures in the prevailing security posture. It demonstrated the ease with which terrorists could impersonate official personnel, the inadequacy of the on-site armed response, and a delayed reaction from reinforcement units.

Strategic Impact and the Post-Luxor Doctrine

The Luxor Massacre was a watershed moment. The sheer brutality of the attack, particularly the mutilation of victims, provoked a wave of revulsion across Egyptian society, effectively destroying public support for the Islamist insurgency.16 The economic impact was immediate and devastating, as tourist arrivals plummeted, crippling the economies of Luxor and other tourism-dependent regions.17

The state’s response was swift and decisive. President Hosni Mubarak replaced his long-serving Interior Minister, General Hassan Al Alfi, with General Habib el-Adly, signaling a major shift in security policy.20 A massive crackdown on Islamist militants was launched across the country.16 Most importantly for the TAP, the state abandoned its previous security model and adopted a new doctrine of

“security through overwhelming presence.” This doctrine, which remains in effect today, is characterized by a highly visible, heavily armed, and multi-layered security approach. Its key tactical and operational manifestations include:

- Hardened Perimeters: The installation of permanent, hardened security infrastructure at the entrances to all major tourist sites, museums, and hotels. This includes blast walls, vehicle barriers, walk-through metal detectors, X-ray baggage scanners, and heavily armed static guard posts.22

- Mandatory Armed Escorts: The implementation of a now-standard policy requiring armed TAP escorts for all tourist convoys traveling by road between major cities (e.g., Cairo to Alexandria, Luxor to Aswan). For many tour operators, especially those with American clients, an armed officer is required to accompany the group at all times, even within a single city.23

- Increased Manpower and Firepower: A dramatic increase in the sheer number of security personnel deployed in and around tourist areas. It became common to see TAP officers openly carrying assault rifles in addition to their sidearms, a clear visual signal of a heightened state of alert.24

The Luxor Massacre thus directly created the securitized environment that tourists in Egypt experience today. It transformed the TAP’s mission, shifting its focus from conventional policing to front-line counter-terrorism and force protection.

Table 1: Key Security Incidents Targeting Tourists/Sites (1992-Present)

| Date | Location (City) | Target | Attack Type | Perpetrator | Casualties (Killed/Wounded) |

| Oct 1992 | Dayrut | Tour Bus | Shooting | al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya | 1 British tourist killed 18 |

| Sep 1997 | Cairo | Tour Bus (Egyptian Museum) | Grenade/Shooting | al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya | 10 (9 German tourists, 1 Egyptian driver) killed, 8+ wounded 18 |

| Nov 17, 1997 | Luxor | Temple of Hatshepsut | Mass Shooting/Stabbing | al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya | 62 (58 tourists, 4 Egyptians) killed, 26 wounded 16 |

| Apr 2005 | Cairo | Khan el-Khalili Bazaar | Suicide Bombing | Abdullah Azzam Brigades | 3 (1 American, 1 French, 1 Egyptian) killed, 18 wounded 17 |

| Jul 2005 | Sharm El Sheikh | Hotels/Market | Coordinated Bombings | Abdullah Azzam Brigades | ~88 killed, 150+ wounded 20 |

| Jun 2015 | Luxor | Karnak Temple | Attempted Suicide Bombing | ISIS affiliate | 2 terrorists killed, 5 Egyptians wounded; attack thwarted by police 25 |

| Oct 2023 | Alexandria | Pompey’s Pillar | Shooting | Lone Actor (Police Officer) | 3 (2 Israeli tourists, 1 Egyptian guide) killed 26 |

| May 2024 | Alexandria | Tourist Site | Shooting | Unknown | 1 Israeli-Canadian national killed 26 |

V. The 2011 Revolution and its Aftermath: Collapse and Reassertion

If the Luxor Massacre defined the TAP’s counter-terrorism doctrine, the 2011 Revolution and its chaotic aftermath defined its role in state preservation and highlighted the catastrophic consequences of its absence. The period from 2011 to 2013 represented a near-total collapse of the security apparatus, followed by a forceful reassertion that has cemented the police’s central role in the post-revolutionary Egyptian state.

The Security Vacuum (2011-2013)

The 18 days of mass protests that began on January 25, 2011, were characterized by intense and violent confrontations between demonstrators and the police, who were widely seen as the primary instrument of the Mubarak regime’s repression.27 In the face of overwhelming popular anger, the police infrastructure disintegrated. Across the country, an estimated 99 police stations were burned down, and police officers, including the TAP, effectively abandoned their posts and withdrew from the streets.27

This withdrawal created an immediate and profound security vacuum, which had a devastating effect on Egypt’s cultural heritage.30 With no police presence to protect them, archaeological sites, storerooms, and even museums became vulnerable. The period immediately following the revolution saw a dramatic and unprecedented spike in the looting of antiquities. This was not merely opportunistic theft; it was a multi-faceted assault on the nation’s heritage. Organized criminal mafias, some with international connections, exploited the chaos to plunder sites for the global black market. Simultaneously, local villagers, no longer fearing police intervention, began appropriating land on archaeological sites for farming or construction, often conducting their own illegal excavations in the process.7

Sites from Alexandria to Aswan were targeted, with areas in Middle Egypt that had always been minimally policed suffering the most.30 Satellite imagery from this period reveals the shocking scale of the damage, with ancient cemeteries pockmarked by thousands of looters’ pits. The few civilian guards employed by the Ministry of Antiquities were left powerless; they were poorly paid, largely unarmed, and had no police backup to call upon, with several being killed in the line of duty.30 This period stands as a stark illustration of the consequences of a security collapse and serves as a powerful justification, in the eyes of the current regime, for maintaining a robust police presence.

The Post-2013 Reassertion

The military’s removal of President Mohamed Morsi in July 2013 marked another pivotal moment. The new government, led by then-General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, made the restoration of haybat al dawla—”the awe/prestige of the state”—its paramount objective.27 This involved a massive, state-wide effort to re-empower and redeploy the police and security forces as the guarantors of order and stability.8

The TAP was a direct beneficiary of this policy. As security forces re-engaged across the country, often in coordination with the military, the protection of tourist sites and antiquities was prioritized.30 The return of the TAP was framed not as a restoration of the old, repressive police state, but as a necessary action to protect Egypt’s national identity and economic future from the chaos that had engulfed it. This narrative proved politically potent. After years of instability and the visible plundering of their heritage, many Egyptians welcomed the return of a strong security presence.31

This dynamic created a symbiotic relationship between the security apparatus and the legitimacy of the post-2013 government. The visible presence of well-armed, disciplined TAP officers at the Pyramids or the temples of Luxor became a powerful propaganda tool. It signaled to both domestic and international audiences that the state was firmly back in control, capable of protecting its most valuable assets and ensuring the safety of foreign visitors. In this context, the TAP’s effectiveness is measured by the state not only in terms of thwarted attacks but also by its contribution to this broader political narrative of restoring order from chaos. This has made the force politically indispensable to the current regime and helps explain the significant resources allocated to it.

VI. Current Operational Posture in Cairo and Alexandria

The operational posture of the Tourism and Antiquities Police in Egypt’s two largest cities, Cairo and Alexandria, reflects the national doctrine of visible deterrence and layered security, but is tailored to the unique geography and threat profile of each metropolis.

Cairo

As the national capital, the primary port of entry for most tourists, and home to some of the world’s most iconic monuments, Cairo and the adjacent Giza governorate represent the area of highest concentration for TAP assets.32 The operational focus is on securing a handful of globally recognized, high-density sites that are considered prime targets for terrorism. These include the Giza Plateau (Pyramids and Sphinx), the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square and its eventual successor, the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM), the historic Khan el-Khalili bazaar, and the major international hotel chains along the Nile.7

The tactics employed in Cairo exemplify a layered defense-in-depth approach:

- Outer Cordon: Major tourist zones are often ringed by an outer layer of security, consisting of police checkpoints on approach roads that can stop and search suspicious vehicles.

- Perimeter Control: The immediate perimeter of each major site is hardened. This involves a single point of entry and exit for tourists, controlled by walk-through metal detectors, X-ray baggage scanners, and a heavy presence of uniformed, armed TAP officers.22

- Internal Security: Inside the perimeter, security continues with roving patrols of both uniformed and plainclothes officers. These officers are tasked with monitoring crowds for suspicious behavior and responding to any incidents.22

- Convoy Security: Cairo is the starting point for most overland tourist travel. The TAP manages the legally mandated system of armed escorts for tour buses traveling to other destinations like Alexandria or Luxor. This involves daily paperwork filings by tour companies and checks at multiple police checkpoints along the route.24

Alexandria

The security posture in Alexandria is similarly robust but adapted to a different set of sites and a distinct threat environment. The operational focus is on protecting key Greco-Roman and modern landmarks, such as the Qaitbay Citadel (built on the site of the ancient lighthouse), Pompey’s Pillar, the Catacombs of Kom El Shoqafa, and the modern Bibliotheca Alexandrina.7

Alexandria presents unique challenges. The city has a history of sectarian tensions and has recently become the location for a different kind of threat: the lone-actor insider attack.5 In October 2023, a police officer assigned to provide security services at a tourist site opened fire on a group of Israeli tourists, killing two of them and their Egyptian guide.26 In May 2024, another shooting attack in the city killed an Israeli-Canadian national.26 These incidents highlight a significant vulnerability in the Egyptian security model. While the layered defense is effective at stopping external assaults by organized groups, it is far less effective against a radicalized individual who is already part of the security apparatus or can operate without raising suspicion.

The tactical response in Alexandria to these attacks has likely involved an enhancement of counter-surveillance measures, including a greater deployment of plainclothes officers to monitor both crowds and other security personnel for signs of radicalization or suspicious behavior. There is also likely a heightened state of alert for officers guarding sites known to be frequented by specific nationalities that are high-profile targets for extremists.

VII. Armament, Equipment, and Training

The Tourism and Antiquities Police is an armed, para-militarized force whose equipment reflects the serious nature of the threats it is expected to counter. Its personnel are equipped with modern small arms and supported by a range of vehicles and communications systems consistent with a front-line security unit.

Small Arms

TAP officers carry the same standard-issue weapons as the broader Egyptian National Police, with armament varying based on role and assignment.7 The force’s arsenal is a mix of domestically produced and imported firearms.

- Standard Sidearms: The most common sidearm for officers on general patrol is the domestically manufactured Helwan 920, a licensed copy of the Italian Beretta 92FS pistol, chambered in 9x19mm.35 In recent years, the police have diversified their inventory, and it is also common to see officers carrying imported 9mm pistols such as the

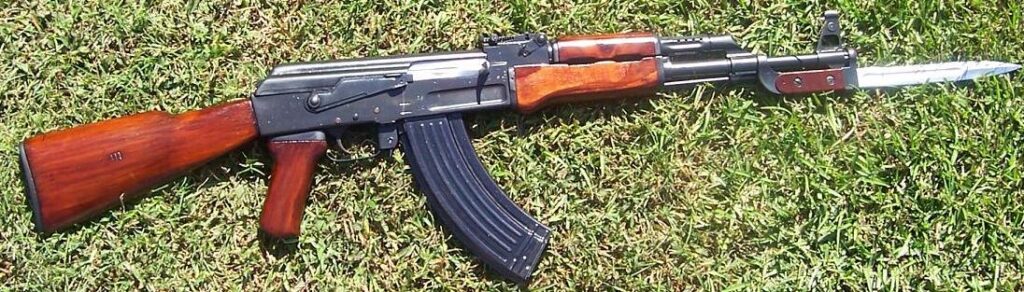

CZ 75B, Glock 17, and various SIG Sauer models.7 A major purchase of 100,000 new 9mm pistols was approved in 2013 to upgrade and standardize the force’s sidearms following the revolution.36 - Long Guns: Reflecting the post-Luxor doctrine of visible deterrence and increased firepower, it is standard practice for TAP officers at static guard posts and on escort details to be armed with long guns. The most prevalent of these is the AKM-pattern assault rifle, most likely the Egyptian-made Maadi ARM variant chambered in 7.62x39mm.35 For close-quarters situations or specialized units, the German-made

Heckler & Koch MP5 submachine gun in 9x19mm is also widely used.7

The use of military-caliber assault rifles as a standard tool for a police unit underscores the para-militarized nature of the TAP and the state’s perception of the threat level as being equivalent to a low-intensity conflict.

Table 2: Standard Issue & Available Small Arms of the Tourism & Antiquities Police

| Weapon Type | Model(s) | Caliber | Origin | Typical User/Role |

| Pistol | Helwan 920 (Beretta 92FS) | 9x19mm | Egypt/Italy | Standard Officer Sidearm 35 |

| Pistol | CZ 75B | 9x19mm | Czech Republic | Officer Sidearm 7 |

| Pistol | Glock 17 | 9x19mm | Austria | Officer Sidearm 7 |

| Pistol | SIG Sauer P226 | 9x19mm | Switzerland | Officer Sidearm 35 |

| Submachine Gun | Heckler & Koch MP5 / MP5K | 9x19mm | Germany | Static Guard, Escort Detail, Special Units, Close Protection 49 |

| Carbine / SMG | CZ Scorpion Evo 3 A1 | 9x19mm | Czech Republic | Law Enforcement Units, Special Units 50 |

| Assault Rifle | Maadi ARM (AKM variant) | 7.62x39mm | Egypt/Soviet Union | Static Guard, Escort Detail, Checkpoints 35 |

Vehicles and Communications

The TAP utilizes a fleet of vehicles appropriate for its diverse roles. Standard marked police sedans and SUVs are used for general patrols in urban areas like Cairo and Alexandria. For escorting tourist convoys, especially in more remote areas, pickup trucks with mounted machine guns or armored vehicles may be used. Open-source analysis has identified French-made Sherpa light armored vehicles bearing police license plates and markings in use by Egyptian security forces, including in counter-terrorism operations, suggesting their availability to high-risk police units.38

Communications are tightly controlled by the Egyptian state. The private use of satellite phones and certain types of radio communications equipment is illegal without a specific permit from the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology.39 This indicates that the police, military, and other state security bodies operate on their own secure, and likely encrypted, radio networks to prevent monitoring by hostile actors. The national emergency number for the Tourist Police is 126, a dedicated line for tourists to report crimes or request assistance.26

VIII. The Military-Police Nexus: Cooperation and Conflict

The relationship between the Ministry of Interior’s police forces and the Egyptian Armed Forces is a critical, and often fraught, element of the national security landscape. While the two entities cooperate against common threats, they are also vast, powerful, and historically rivalrous institutions. This dynamic of cooperation and conflict directly impacts the security of tourists, particularly in areas where their jurisdictions overlap.

Delineation of Responsibilities

In principle, the division of labor is clear: the MOI and its police forces, including the TAP, are responsible for internal security and law enforcement, while the EAF is tasked with defending the nation from external threats.8 However, since the 2011 Revolution and the subsequent escalation of the counter-terrorism campaign, particularly after 2013, these lines have become significantly blurred. The Egyptian military is now deeply involved in internal security operations, most notably in the North Sinai governorate and the vast Western Desert, which borders Libya.29 This creates a complex operational environment where police and military units must frequently interact and deconflict their activities.

Models of Cooperation

Formal mechanisms for cooperation do exist and are frequently utilized.

- Joint Operations: In active counter-insurgency zones like North Sinai, it is standard practice for the army and police to conduct joint patrols, raids, and checkpoint operations.42 The very language used by the government to describe security actions often refers to a “joint police and army force”.44

- Jurisdictional Handoffs: A clear example of formal coordination relates to travel in restricted areas. For tourists to access Egypt’s sensitive border zones (with Libya, Sudan, or Israel) or to travel off-road in parts of the Sinai Peninsula, their tour operator must obtain permits and a pre-approved travel route from both Military Intelligence and the Tourist Police Headquarters.45 This dual-approval process demonstrates a formal, high-level mechanism for deconfliction. On the ground, it is often military checkpoints that enforce these travel restrictions, turning back any tourist groups that lack the proper authorization.24

Case Study: The 2015 Western Desert Incident

Despite these formal mechanisms, the potential for catastrophic failure in coordination remains a significant risk. This was tragically demonstrated on September 13, 2015, when Egyptian security forces—reportedly including an army helicopter—attacked a convoy of four-wheel-drive vehicles in the Western Desert, killing 12 people and injuring 10. The victims were not terrorists, but a group of Mexican tourists and their Egyptian guides.44

The incident exposed a calamitous breakdown in command, control, and communications (C3) between the military and the police/tourism authorities. According to the chairman of the Tour Guides Syndicate, the tourist group had obtained all the necessary permits from the Interior Ministry for their trip, refuting initial government claims that they were in a restricted area.44 This strongly implies that the military unit that ordered and executed the strike was operating without full situational awareness provided by their MOI counterparts. The failure was not a lack of policy, but a failure of execution. The deconfliction process, designed to prevent exactly this type of tragedy, broke down.

This incident cannot be dismissed as a simple accident. It is symptomatic of a deeper, systemic challenge rooted in the institutional cultures of Egypt’s two main coercive bodies. The military, which views itself as the ultimate guardian of national sovereignty, and the Ministry of Interior, which fiercely protects its own authority over internal security, are natural rivals for resources, influence, and prestige. This can lead to information hoarding, a lack of seamless interoperability, and a mindset where one service may act unilaterally in its designated zone of operations without fully integrating intelligence from the other. This underlying institutional friction remains one of the most significant latent threats to tourist safety in Egypt’s remote regions, where a fully vetted and officially approved tour group can still be caught in the crossfire of a poorly coordinated military action.

IX. Assessment of Effectiveness and Enduring Challenges

The Tourism and Antiquities Police has evolved into a central pillar of Egypt’s national security strategy. An overall assessment of its effectiveness reveals a force with significant strengths in its core mission of protecting high-profile targets, but one that is also beset by systemic weaknesses and faces an evolving set of future challenges.

Strengths

- Deterrence of Mass-Casualty Attacks: The single greatest success of the TAP and the post-Luxor security doctrine has been the prevention of another large-scale, coordinated massacre at a major tourist hub. The combination of hardened perimeters, a heavy armed presence, and mandatory escorts has significantly raised the operational cost and complexity for any terrorist group attempting such an attack. This visible deterrence has been highly effective.31

- High State Priority: Because tourism is inextricably linked to economic stability and the political legitimacy of the regime, the TAP receives a high degree of political attention and a commensurate allocation of resources. This ensures the force is generally well-manned and equipped to handle its primary responsibilities.23

- Improved Public Perception of Safety: Despite international travel advisories and concerns over police methods, the robust security measures have contributed to a tangible sense of safety for many tourists and a renewed confidence among the Egyptian public. Gallup’s 2018 “Law and Order Index” gave Egypt a high score, reflecting citizens’ confidence in local police and a feeling of safety, a stark contrast to the chaos of the immediate post-revolutionary years.31

Weaknesses and Enduring Challenges

- Systemic Police Issues: The TAP is an integral part of the Egyptian National Police and is therefore not immune to the systemic problems that affect the entire institution. These include long-standing issues with corruption, accusations of brutality and human rights abuses in other contexts, and a general lack of independent accountability.9 Such issues can degrade professionalism, erode public trust, and create security vulnerabilities.

- Vulnerability to Lone-Actor and Insider Threats: As the 2023 Alexandria shooting demonstrated, the current security model is optimized to defeat an external, conventional assault. It is far more vulnerable to the threat of a self-radicalized lone actor, particularly an insider who is already part of the security system. This type of threat bypasses the hardened perimeters and visible deterrents that form the core of the TAP’s strategy.

- The Impossibility of Scale: While the state can effectively secure a few dozen high-profile sites in Cairo, Alexandria, and Luxor, it lacks the resources to provide the same level of protection to the thousands of archaeological sites scattered across the vastness of Egypt. These remote locations remain highly vulnerable to looting and illegal encroachment, a battle the TAP and the Ministry of Antiquities are consistently losing.30

- Military-Police Deconfliction: The 2015 friendly fire incident in the Western Desert remains the most potent example of a critical and potentially fatal weakness in the Egyptian security system. The risk of miscommunication and failed coordination between the MOI and the EAF in remote operational areas persists, posing a direct threat to any tourist activity in those regions.44

Outlook

The primary threat to tourist security in Egypt has evolved. The danger posed by large, hierarchical insurgent groups like al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya in the 1990s has been largely supplanted by the threat from smaller, decentralized cells affiliated with transnational ideologies like ISIS, and, perhaps most acutely, from self-radicalized lone actors. The future challenge for the Tourism and Antiquities Police will be to adapt its doctrine accordingly. A strategy based on overwhelming static defense and brute force must evolve to become more intelligence-led, agile, and capable of identifying and neutralizing these more subtle and unpredictable threats. The force must do this while continuing to navigate the fundamental paradox of its mission: to be an effective, intimidating security force without creating an environment so visibly oppressive that it frightens away the very international visitors it is sworn to protect.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

| The author would like to personally thank the TAP for their courtesy and professionalism during his visit to Alexandria and Cairo in October 2025. |

Sources Used

- Ancient Egyptian Police: Facts, Medjay, Duties, Innovations & Legacy – Egypt Tours Portal, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.egypttoursportal.com/en-gb/blog/ancient-egyptian-civilization/ancient-egypt-police/

- The Police in Ancient Egypt: Guardians of Order and Justice, accessed October 4, 2025, https://egypttourmagic.com/the-police-in-ancient-egypt/

- Police in Ancient Egypt: 10 Remarkable Facts Revealed, accessed October 4, 2025, https://egyptunitedtours.com/police-in-ancient-egypt/

- 96 – The police in ancient Egypt – Egypt Magic Tours, accessed October 4, 2025, https://egyptmagictours.com/egypt-magic-637-the-police-in-ancient-egypt/

- Police in Ancient Egypt – From Medjay to Centurion DOCUMENTARY – YouTube, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ASiDbLGezqg

- Discover the Police Museum – A Unique Cairo Attraction – Ask Aladdin, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.ask-aladdin.com/all-destinations/egypt/category/egypt-museums/page/the-police-museum

- Egyptian National Police – Wikipedia, accessed October 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_National_Police

- In Egypt, the Police are Soldiers for the Regime Building on traditions dating back to colonialism, Egyptian police today are more militarized, accessed October 4, 2025, https://rosaluxna.org/publications/in-egypt-the-police-are-soldiers-for-the-regime-building-on-traditions-dating-back-to-colonialism-egyptian-police-today-are-more-militarized/

- Egyptian’s Stereotype of the Police, accessed October 4, 2025, http://www.ug-law.com/downloads/Police%20Study-En.pdf

- Tourism in Egypt – Wikipedia, accessed October 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tourism_in_Egypt

- Submitted by The Egyptian Delegation to the Conference Meeting of Open Membership Team of Governmental Experts Concerning – Protection from Illicit Trading in Cultural Property – United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/organized_crime/Egypt.pdf

- Law No. 117 of 1983 as amended by Law No. 3 of 2010 promulgating the Antiquities Protection Law – UNESCO Database of National Cultural Heritage Laws, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.unesco.org/en/cultnatlaws/law-no-117-1983-amended-law-no-3-2010-promulgating-antiquities-protection-law

- LAW NO. 117 OF 1983 – African Archaeology, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.african-archaeology.net/heritage_laws/egypt_law3_2010_entof.pdf

- Establishing a Tourist Facilities in Egypt – Youssry Saleh Law Firm, accessed October 4, 2025, https://youssrysaleh.com/en/establishing-a-tourist-facilities-in-egypt/

- Police Academy, Cairo (Egypt) – Office of Justice Programs, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/police-academy-cairo-egypt

- Luxor massacre | Research Starters – EBSCO, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/politics-and-government/luxor-massacre

- Terrorism and tourism in Egypt – Wikipedia, accessed October 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terrorism_and_tourism_in_Egypt

- Islamic Terrorism in Egypt: Challenge and Response – INSS, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.inss.org.il/wp-content/uploads/systemfiles/Islamic%20Terroeism%20in%20Egypt%20Challenge%20and%20Response028403796.pdf

- 1997 Human Rights Report: Egypt – State Department, accessed October 4, 2025, https://1997-2001.state.gov/global/human_rights/1997_hrp_report/egypt.html

- Luxor massacre – Wikipedia, accessed October 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luxor_massacre

- 1997 Global Terrorism: Africa Overview – State Department, accessed October 4, 2025, https://1997-2001.state.gov/global/terrorism/1997Report/review.html

- Safety Guide For Travelers To Egypt (2025–2026) – Travel2Egypt, accessed October 4, 2025, https://travel2egypt.org/safety-guide-for-travelers-to-egypt/

- Egypt Safety for Tourists Travel Guide, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.inside-egypt.com/resources/travel-safety.html

- Is Egypt Safe for Tourists? – Inertia Network, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.inertianetwork.com/magazine/is-egypt-safe-for-tourists

- Comment by the Information and Press Department on the terrorist attack in Luxor, Egypt – The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/1510219/

- Safety and security – Egypt travel advice – GOV.UK, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.gov.uk/foreign-travel-advice/egypt/safety-and-security

- The resurgence of police government in Egypt – Project on Middle …, accessed October 4, 2025, https://pomeps.org/the-resurgence-of-police-government-in-egypt

- Egypt in the Aftermath of the Arab Spring – ACCORD, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.accord.org.za/conflict-trends/egypt-aftermath-arab-spring/

- Counter-Terrorism Policies in Egypt: Effectiveness and Challenges – IEMed, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.iemed.org/publication/counter-terrorism-policies-in-egypt-effectiveness-and-challenges/

- The Loss and Looting of Egyptian Antiquities – Middle East Institute, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.mei.edu/publications/loss-and-looting-egyptian-antiquities

- Egyptians feel safer but at high cost for security forces | | AW – The Arab Weekly, accessed October 4, 2025, https://thearabweekly.com/egyptians-feel-safer-high-cost-security-forces

- Is it safe to travel to Egypt? Safety & Security in Egypt, accessed October 4, 2025, https://egypttimetravel.com/safe-to-travel-to-egypt/

- Is it Safe to Travel to Egypt?, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.egyptadventurestravel.com/blog/is-it-safe-to-travel-to-egypt

- Is It Safe to Travel to Alexandria? Safe Cities in Egypt – EgyptaTours, accessed October 4, 2025, https://egyptatours.com/is-it-safe-to-travel-to-alexandria/

- List of equipment of the Egyptian Army – Wikipedia, accessed October 4, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_equipment_of_the_Egyptian_Army

- Egypt will give police new guns – The Spokesman-Review, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.spokesman.com/stories/2013/feb/17/egypt-will-give-police-new-guns/

- Egyptian Rifles: FN49, Hakim, Rasheed, & Maadi – YouTube, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XXv3K_Isl2A

- Egyptian police and the french-made armored vehicles – Disclose.ngo, accessed October 4, 2025, https://disclose.ngo/en/article/egyptian-police-and-the-french-made-armored-vehicles

- Egypt Travel Advice & Safety | Smartraveller, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.smartraveller.gov.au/destinations/africa/egypt

- useful information – Experience Egypt, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.experienceegypt.eg/en/usefulinfo

- Safety and Security in Egypt: A Complete Travel Guide – Memphis Tours, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.memphistours.com/egypt/egypt-wikis/egypt-information/wiki/safety-and-security

- If You Are Afraid for Your Lives, Leave Sinai! – Human Rights Watch, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/05/28/if-you-are-afraid-your-lives-leave-sinai/egyptian-security-forces-and-isis

- World Report 2023: Egypt | Human Rights Watch, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/egypt

- Egypt defends ‘mistake’ killing of 12 tourists – Dailynewsegypt, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.dailynewsegypt.com/2015/09/14/egypt-defends-mistake-killing-of-12-tourists/

- Egypt Travel Advisory | Travel.State.gov, accessed October 4, 2025, https://travel.state.gov/en/international-travel/travel-advisories/egypt.html

- Egypt Traveler Information – AARDY.com, accessed October 4, 2025, https://www.aardy.com/blog/egypt-traveler-information-travel-advice/

- Tragic Killing of Mexican Tourists in Egypt Sparks Criticism – Middle …, accessed October 4, 2025, https://mepc.org/commentaries/tragic-killing-mexican-tourists-egypt-sparks-criticism/

- Effectiveness and Legitimacy of State Institutions in Egypt – GOV.UK, accessed October 4, 2025, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5d5553b3ed915d08e047cb8a/621_Legitimacy_of_the_State_and_Institutions_in_Egypt.pdf

- MP5 – Heckler & Koch, accessed October 5, 2025, https://www.heckler-koch.com/en/Products/Military%20and%20Law%20Enforcement/Submachine%20guns/MP5

CZ Scorpion Evo 3 – Wikipedia, accessed October 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CZ_Scorpion_Evo_3