Executive Summary

The transformation of near-Earth space from a global commons of scientific inquiry into a contested warfighting domain is now operationally complete. This report, synthesized by a team of national security analysts, intelligence specialists, and space warfare strategists, offers a comprehensive net assessment of the global distribution of space power as of early 2026. The analysis proceeds from the foundational premise that space superiority is no longer merely an enabler of terrestrial operations but a prerequisite for national survival in high-intensity conflict. The ability to access orbit, maneuver within it, and deny that access to adversaries has become the central nervous system of modern military power.

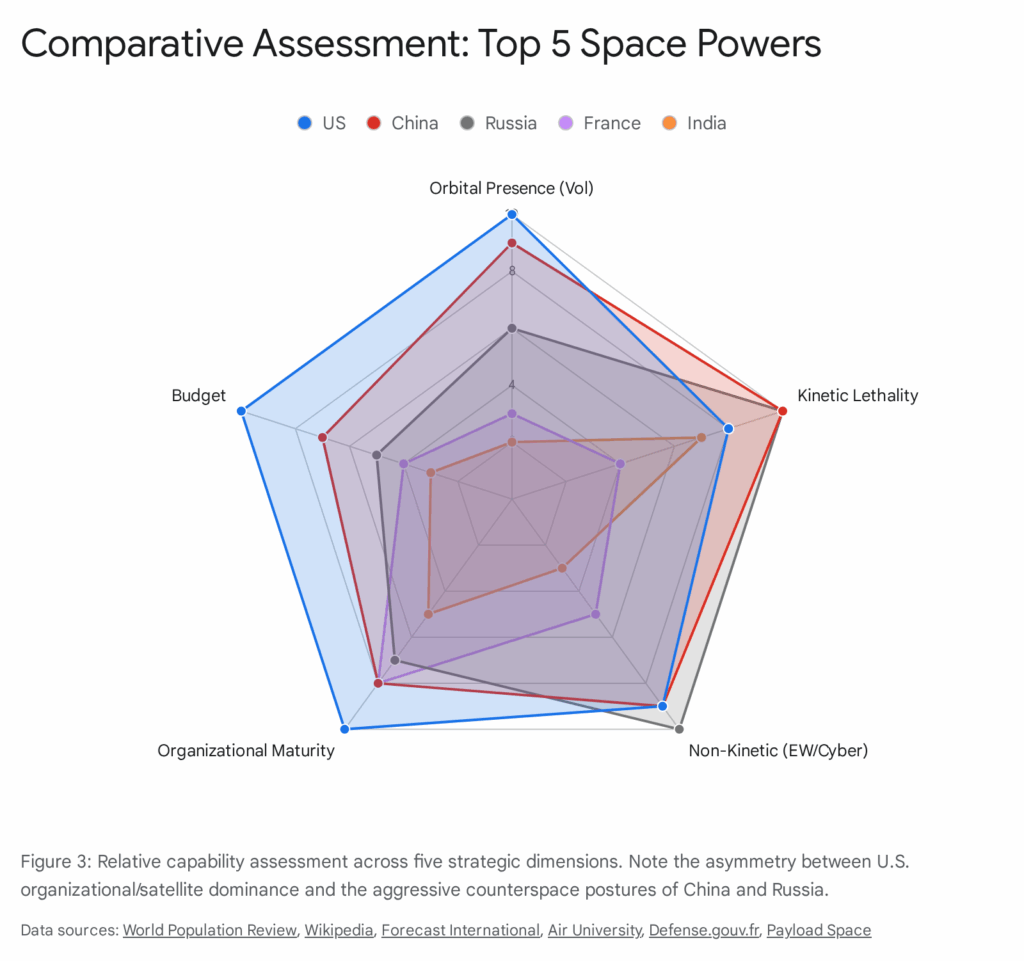

Our assessment indicates that the unipolar moment of United States space dominance has ended. A multipolar security environment has emerged, characterized by the aggressive development of counterspace capabilities by peer competitors and the rapid proliferation of dual-use technologies among middle powers. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has achieved near-parity in specific counterspace vectors, notably in co-orbital robotics and directed energy, while the Russian Federation retains a potent, battle-tested electronic warfare (EW) arsenal capable of holding critical orbital regimes at risk. Simultaneously, a “second tier” of space powers—led by France, India, and Japan—is operationalizing doctrines of “active defense,” fundamentally altering the strategic calculus by introducing independent deterrence mechanisms into the orbital domain.

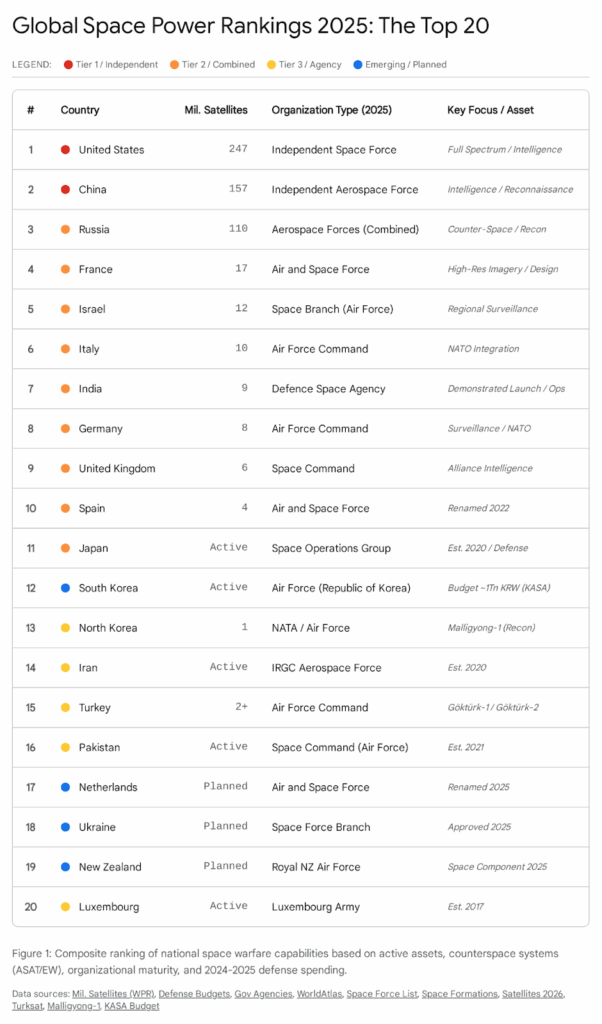

The following assessment identifies the top twenty nations possessing significant military space capabilities. This ranking is derived not merely from satellite quantity but from a weighted analysis of kinetic and non-kinetic lethality, organizational maturity, industrial resilience, and the integration of space assets into joint force operations.

Data Table: Global Space Power Rankings 2025

| Rank | Country | Est. Mil. Sats | Kinetic ASAT | Electronic Warfare | Dedicated Command | Strategic Focus |

| 1 | United States | ~247+ | Yes (DA-ASAT) | High (CCS 10.2) | USSF | Space Superiority / Resilience |

| 2 | China | ~157+ | Yes (DA-ASAT) | High (Jam/Cyber) | PLASSF | Counter-Intervention / Info Dominance |

| 3 | Russia | ~110+ | Yes (Nudol) | High (Tirada) | VKS | Threat Negation / EW Coercion |

| 4 | France | ~17 | No (Dev. Laser) | Med (Planned) | CDE | Active Defense / Strategic Autonomy |

| 5 | India | ~9 | Yes (Shakti) | Low (Dev.) | DSA | Regional Deterrence / ASAT |

| 6 | Japan | ~10-15 | No (Interceptor) | Med (Dev.) | SOG | SDA / Missile Defense Support |

| 7 | United Kingdom | ~6 | No | Med (SkyNet) | UKSC | Integration / Allied Support |

| 8 | Israel | ~12 | Yes (Arrow-3*) | Med (Jamming) | Sp. Branch | Missile Defense / Reconnaissance |

| 9 | Germany | ~8 | No | Med (Radar) | WRKdo | Space Situational Awareness / SAR |

| 10 | Italy | ~10 | No | Low (Comms) | COS | Dual-Use Comms / Observation |

| 11 | South Korea | ~5 | No | Low (Dev.) | Sp. Op. | Reconnaissance (425) / Kill Chain |

| 12 | Australia | ~4 | No | Low (Dev.) | DSC | SDA / Resilient Comms |

| 13 | Iran | ~2-3 | No | Med (Jamming) | IRGC | Asymmetric / Launch Vehicle Dev. |

| 14 | North Korea | ~1-2 | No | Low (Jamming) | NATA | Reconnaissance / ICBM Support |

| 15 | Spain | ~4 | No | Low | SASF | Secure Comms (SpainSat NG) |

| 16 | Turkey | ~6 | No | Low | TSA | Reconnaissance (Göktürk) |

| 17 | UAE | ~3 | No | Low | UAESA | Imagery Intelligence (Falcon Eye) |

| 18 | Canada | ~4 | No | Low | 3 CSD | Surveillance (Sapphire) / SAR |

| 19 | Brazil | ~1 | No | Low | COPE | Secure Comms (SGDC) |

| 20 | Saudi Arabia | ~2 | No | Low | SSA | Comms / Dual-Use Imagery |

Note: Israel’s Arrow-3 is primarily a missile defense interceptor but possesses inherent exo-atmospheric capabilities theoretically applicable to ASAT roles.

1. The Strategic Significance of Space Power

To comprehend the stakes of the current geopolitical competition, one must first dismantle the misconception that space is a peripheral domain. In 2025, space is not merely an adjunct to terrestrial warfare; it is the strategic center of gravity for global power projection. The significance of space capabilities stems from their role as the foundational infrastructure for C4ISR (Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance) and PNT (Positioning, Navigation, and Timing). Without these space-based enablers, modern militaries revert to the operational limitations of the mid-20th century.

1.1 The Central Nervous System of Modern Warfare

In the pre-space era, the “fog of war” was an accepted constant, limiting commanders to line-of-sight communications and delayed intelligence. Space power has thinned this fog, providing a “god’s eye view” that creates near-real-time transparency of the battlefield. The ability to see, hear, and direct forces globally is entirely dependent on orbital assets.

For instance, the command and control (C2) of a drone operating in the Middle East by a pilot in Nevada is physically impossible without satellite communications (SATCOM) to bridge the curvature of the Earth.1 Similarly, the projection of naval power relies on satellites to track adversary fleets and coordinate carrier strike groups across vast oceans. Capabilities such as the Chinese and Russian robust space-based ISR networks now allow them to monitor, track, and potentially target U.S. and allied forces worldwide, fundamentally challenging the assumption of unhindered American expeditionary warfare.2

1.2 The Precision and Lethality Revolution

The lethality of modern warfare is inextricably linked to PNT services provided by constellations like GPS (USA), Galileo (EU), BeiDou (China), and GLONASS (Russia). These systems provide the invisible timing signals necessary to synchronize encrypted communications and guide precision-guided munitions (PGMs).1 A Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM), for example, relies on GPS to achieve accuracy within meters. If this signal is jammed or spoofed, the munition becomes a “dumb bomb,” requiring more sorties and risking greater collateral damage to achieve the same effect.3

Consequently, the disruption of PNT services has become a primary objective for adversaries. Iranian and North Korean forces have already demonstrated jamming capabilities to disrupt civil and military operations, illustrating that the “barrier to entry” for space warfare is lower than often assumed.2

1.3 Missile Warning and Nuclear Stability

Perhaps the most critical function of military space power is its role in strategic stability. Satellites equipped with infrared sensors—such as the U.S. Space Based Infrared System (SBIRS) and its successor, the Next-Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared (Next-Gen OPIR)—provide the only reliable means of detecting the heat signatures of ballistic missile launches in their boost phase.4 This “strategic warning” is the trigger for nuclear decision-making.

The emergence of hypersonic glide vehicles (HGVs) has further elevated the importance of space-based sensing. Because HGVs fly lower and maneuver unpredictably compared to ballistic missiles, terrestrial radars have limited detection horizons due to the Earth’s curvature. Only a proliferated space sensor layer can track these threats continuously from launch to impact.5 Therefore, an attack on early-warning satellites is not merely a tactical move; it is a strategic signal that could be interpreted as a prelude to a nuclear first strike, creating a dangerous escalation dynamic known as the “Space-Nuclear Nexus”.6

2. Theoretical Frameworks: The “High Ground” and its Limits

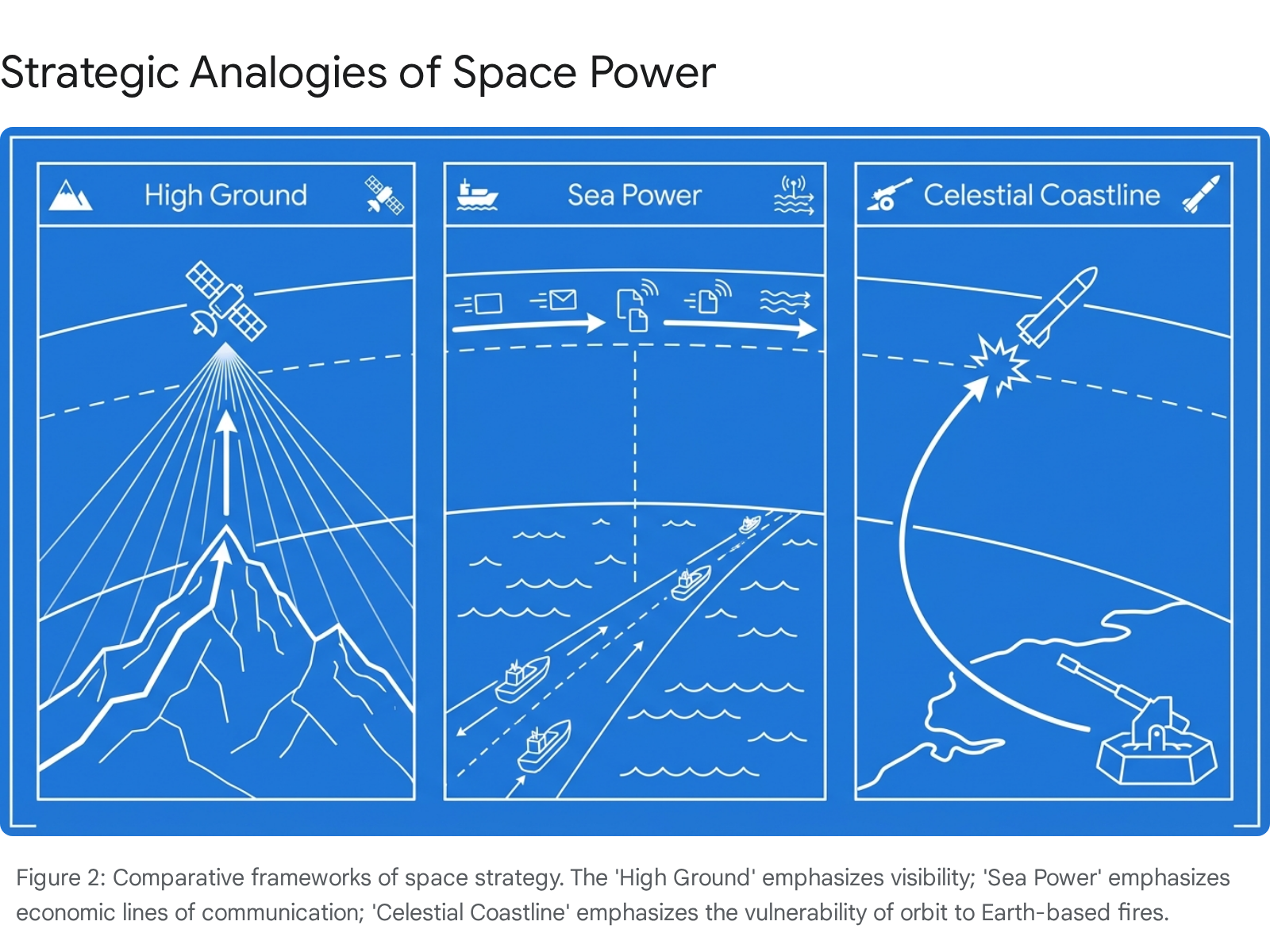

Strategic thought regarding space has historically relied on analogies to terrestrial domains—land, sea, and air—to explain the complex physics and geopolitics of orbit. While useful, these analogies often fail to capture the unique orbital mechanics that govern the domain.

2.1 The “Ultimate High Ground” Analogy

The most pervasive analogy describes space as the “ultimate high ground.” In land warfare, holding the high ground offers a decisive advantage in visibility and the range of fire—gravity aids the projectile moving downward.

- Parallels: This analogy holds true for surveillance and visibility. A satellite in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) or Geostationary Orbit (GEO) possesses an unobstructed line of sight over deep adversary territory, much like a scout on a mountain peak.3 This global visibility forces adversaries to invest heavily in concealment and mobility, imposing a constant cost on their operations.

- Divergence: The analogy fails in the context of maneuver. Unlike a soldier on a hill who can stop, turn, or dig in, a satellite is in a state of constant freefall, governed by Keplerian mechanics.7 It cannot “stop” without falling out of orbit. Its path is predictable days in advance, making it a sitting duck for ground-based interceptors unless it expends precious, finite fuel to maneuver. As strategic theorist Bleddyn Bowen argues, space is not a static hill to be conquered but a dynamic environment where “command” is fleeting.7

2.2 The “Command of the Sea” Analogy (Mahanian View)

Many modern strategists prefer the naval analogy, viewing space as a “cosmic blue water.” This framework draws on Alfred Thayer Mahan’s theories of sea power.

- Lines of Communication: Just as Mahan argued that sea power exists to protect Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs) for trade, space power exists to protect “Celestial Lines of Communication” (CLOCs) for data.8 The global economy depends on the free flow of information through space just as it depends on the flow of goods across the oceans.1

- Chokepoints: The sea has straits (Malacca, Hormuz); space has orbital slots and launch windows. The Geostationary belt is a limited natural resource, and access to specific orbits can be contested. “Commanding” space, in this view, means ensuring one’s own access while denying it to the enemy.8

- Fleet in Being: A space force acts as a “fleet in being.” Its mere existence restricts the enemy’s freedom of action. The knowledge that a reconnaissance satellite will pass overhead at a specific time forces an adversary to halt operations, suppressing their tempo without a single shot being fired.

2.3 The “Command of the Air” Analogy (Douhetian View)

Giulio Douhet’s air power theory emphasizes the offensive, arguing that “the bomber will always get through” and that air superiority is the prerequisite for all other operations.

- Parallels: This is the most alarming analogy. If space is like the air, then Space Superiority is the prerequisite for victory on Earth.3 If an adversary can “blind” the U.S. (deny space superiority), the U.S. cannot effectively conduct air or naval operations. This creates a “first-mover advantage,” incentivizing preemptive strikes against satellites to blind the enemy before they can strike back.

- Active Defense: Just as air power evolved from passive reconnaissance planes to fighters capable of shooting down other planes, space is evolving from passive observation to “active defense.” Concepts like France’s “Yoda” bodyguard satellites mirror the development of fighter escorts—assets designed specifically to protect high-value platforms from enemy interceptors.9

2.4 The “Celestial Coastline” (A Nuanced View)

A more sophisticated analogy is the “Coastal” or “Littoral” analogy.8 Space is not a distant ocean but a coastline immediately adjacent to Earth. Events in space have immediate, tactical effects on the ground. Just as coastal artillery can deny the use of the sea to a navy, Earth-based ASATs (missiles, lasers) can deny the use of space to satellites. This implies that space warfare will not just be “satellite vs. satellite” (dogfights) but “Earth vs. space” (surface-to-air fires).

3. Global Space Warfare Capabilities: The Top Five

The landscape of space warfare is dominated by three established superpowers and two rapidly ascending challengers who have carved out unique strategic niches.

3.1 United States of America

Strategic Posture: Space Superiority and Resilience

The United States remains the undisputed hegemon in space, possessing the largest number of military satellites and the most integrated space architecture. However, this dominance is increasingly fragile due to the heavy reliance of the U.S. military on space for every aspect of its operations.

- Organizational Structure: The U.S. Space Force (USSF), established in 2019, is the world’s first and only independent military service branch dedicated solely to space. It organizes, trains, and equips forces for the U.S. Space Command (USSPACECOM), the unified combatant command responsible for warfighting operations.3

- Capabilities:

- Offensive Space Control: The USSF operates the Counter Communications System (CCS) Block 10.2.11 This is a transportable, ground-based electronic warfare system capable of reversibly denying adversary satellite communications (SATCOM). By jamming enemy links, the U.S. can disrupt command and control without creating permanent orbital debris.

- Space Situational Awareness (SSA): The U.S. maintains the world’s most comprehensive Space Surveillance Network (SSN), utilizing ground-based radars and the GSSAP (Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program) satellites. These assets drift near the GEO belt to inspect other objects, providing attribution and intelligence on potential threats.13

- Resilience: Recognizing the vulnerability of large, expensive satellites, the U.S. is shifting toward “Proliferated Warfighter Space Architectures” (PWSA). This strategy involves launching hundreds of smaller satellites into LEO, creating a mesh network that is resilient to attack—destroying one node has negligible impact on the whole system.14

- Budget: The U.S. military space budget is unrivaled, estimated at over $53 billion for 2024 alone.15

3.2 People’s Republic of China (PRC)

Strategic Posture: Counter-Intervention and Information Dominance

China views space as the “soft underbelly” of U.S. military power. Its strategy focuses on “assassin’s mace” weapons—asymmetric capabilities designed to negate the advantages of a technologically superior foe.

- Organizational Structure: Space operations are centralized under the PLA Strategic Support Force (PLASSF) (noting recent reorganizations that continue to emphasize integrated information warfare). This structure reflects a doctrine of “Informationized Warfare,” where space, cyber, and electronic warfare are fused into a single operational domain.16

- Capabilities:

- Kinetic ASAT: China demonstrated its kinetic capability in 2007 by destroying a weather satellite with a direct-ascent missile. It continues to field operational ground-based missiles (such as the SC-19) capable of destroying LEO satellites.15

- Co-Orbital Grapplers: The Shijian (SJ) series of satellites have demonstrated sophisticated dual-use capabilities. Shijian-17 and Shijian-21 are equipped with robotic arms, ostensibly for debris mitigation. However, in 2022, SJ-21 successfully towed a defunct Beidou satellite to a graveyard orbit.18 In a wartime scenario, this capability could be repurposed to physically capture or de-orbit adversary assets.19

- Directed Energy: China has developed ground-based laser systems capable of “dazzling” (blinding) or damaging the optical sensors of reconnaissance satellites.2

- Scale: China operates over 157 military satellites 21 and maintains a rapid launch cadence, launching 43 military satellites in 2024 alone.22

3.3 Russia

Strategic Posture: Threat Negation and Coercion

Russia, inheriting the vast Soviet space legacy, retains deep expertise but faces resource constraints. Its doctrine emphasizes the denial of space to adversaries to offset its conventional military inferiority.

- Organizational Structure: Space operations are managed by the Russian Aerospace Forces (VKS), which integrates air and space defenses.23

- Capabilities:

- Direct Ascent ASAT: In November 2021, Russia demonstrated the Nudol system (PL-19) by destroying a defunct Soviet satellite (Cosmos 1408), creating a massive debris field that threatened the International Space Station.24 This test confirmed Russia’s possession of a mobile, operational ASAT capability.

- Electronic Warfare (EW): Russia is a global leader in high-power jamming. Systems like Tirada-2 and Bylina-MM are designed to jam communications and reconnaissance satellites from the ground.2 The pervasive use of GPS spoofing in the Ukraine conflict demonstrates the operational maturity of these systems.26

- Co-Orbital “Inspectors”: Russian satellites, such as Cosmos 2542 and 2543, have been observed shadowing U.S. KH-11 spy satellites, behaving in ways that suggest an inspection or weaponization role. In one instance, a Russian satellite released a high-speed projectile into orbit, signaling a potential kinetic capability.13

- Scale: Russia operates approximately 110 military satellites 21, utilizing them for strategic warning and targeting support.

3.4 France

Strategic Posture: Active Defense and Strategic Autonomy

France has emerged as the leading European military space power, breaking from the continent’s traditionally passive stance to adopt a doctrine of “Active Defense.”

- Organizational Structure: In 2019, France established the Commandement de l’Espace (CDE) (Space Command) within the renamed Air and Space Force.28

- Capabilities:

- YODA Program: The Yeux en Orbite pour un Démonstrateur Agile (Eyes in Orbit for an Agile Demonstrator) program aims to develop patrol satellites capable of detecting and maneuvering around hostile satellites in GEO.9 These “bodyguard” satellites are designed to protect high-value French assets (like the Syracuse communications satellites) from inspection or attack.29

- Laser Weapons: France is developing the BLOOMLASE program, a ground-based laser system intended to dazzle spy satellites passing over French territory, denying them imagery of sensitive sites.30

- Surveillance: France operates the GRAVES radar system, a unique asset in Europe for tracking satellites in Low Earth Orbit.

- Philosophy: France explicitly reserves the right to use kinetic or non-kinetic means to defend its assets, a significant doctrinal shift for a medium power.31

3.5 India

Strategic Posture: Regional Deterrence and Sovereign Capability

India has entered the elite club of space powers with a demonstration of “hard power,” driven primarily by the need to deter China and Pakistan.

- Organizational Structure: The Defence Space Agency (DSA) was established to aggregate space assets from the Army, Navy, and Air Force, creating a joint command structure.32

- Capabilities:

- Kinetic ASAT (Mission Shakti): In 2019, India successfully conducted a kinetic ASAT test, destroying one of its own satellites (Microsat-R) with a PDV Mk-II interceptor missile.32 This test made India only the fourth nation to demonstrate such a capability, signaling to regional adversaries that it can hold their assets at risk.

- ISR & ELINT: India operates dedicated military satellites like GSAT-7 (Naval communications) and EMISAT (Electronic Intelligence).33 The RISAT series provides radar imaging capabilities crucial for all-weather monitoring of the Himalayan border regions.34

- Strategic Context: India’s space posture is defensive-deterrent. The development of ASAT capability is viewed as a necessary equalizer in a region where both primary adversaries (China and Pakistan) are advancing their own missile and space technologies.35

4. Extended Analysis: The “Top 20” Context

Beyond the superpowers and the rising giants, the global distribution of space power is widening. A diverse array of nations is investing in military space capabilities, ranging from committed U.S. allies integrating their architectures to asymmetric challengers seeking to disrupt the status quo.

4.1 The “Integrators”: NATO and Five Eyes Allies

These nations are characterized by their deep integration with U.S. space architectures. Their strategy is one of interoperability and niche specialization, contributing specific capabilities (like radar or secure communications) to the broader alliance network.

- Japan (Rank 6): Historically bound by pacifist constraints, Japan is rapidly pivoting its space posture in response to threats from North Korea and China. The Space Operations Group (SOG) was established within the Air Self-Defense Force to monitor the space domain.36 Japan operates the Quasi-Zenith Satellite System (QZSS), a regional PNT constellation that enhances GPS accuracy over Japan. Strategically, Japan is focusing heavily on Space Domain Awareness (SDA) and is developing a dedicated SDA satellite for launch in 2026 to track “killer satellites”.37 The 2025 defense budget, a record high, includes funding for these “interceptor” concepts and deeper integration with U.S. Space Command.38

- United Kingdom (Rank 7): The UK established its own Space Command in 2021, emphasizing its role as a key integrator within the Five Eyes intelligence alliance.10 While the UK currently lacks an indigenous launch capability or kinetic ASATs, it is a global heavyweight in satellite manufacturing (via Airbus UK) and secure military communications through the Skynet constellation.39 The UK’s strategy focuses on allied support, protecting the spectrum, and enhancing orbital tracking from sites like RAF Fylingdales.

- Germany (Rank 9): Germany inaugurated its Space Command (Weltraumkommando) in 2021.40 The Bundeswehr specializes in synthetic aperture radar (SAR) reconnaissance through the SAR-Lupe and SARah systems, which provide all-weather imaging capabilities.40 Germany is also investing in the GESTRA radar system to track space debris and potential hostile objects, contributing to the European SDA picture.41

- Italy (Rank 10): A robust industrial player, Italy operates the COSMO-SkyMed constellation, a dual-use radar system that provides high-resolution imagery for both civil and military users.42 Italy also operates the SICRAL series of military communications satellites 43, ensuring secure command links for its armed forces and NATO allies.

- Australia (Rank 12): Australia’s geography makes it indispensable for Southern Hemisphere space tracking. It hosts critical U.S. C-Band radars and is a core member of the “Combined Space Operations” (CSpO) initiative. While the government recently cancelled the JP9102 single-orbit satellite program in favor of a more resilient, multi-orbit approach 44, Australia remains focused on SDA and ensuring resilient communications for its dispersed forces.45

- Canada (Rank 18): Canada contributes niche expertise in space-based radar surveillance. The Sapphire satellite tracks objects in deep space, contributing to the U.S. Space Surveillance Network. Additionally, the Radarsat Constellation Mission provides maritime domain awareness, crucial for monitoring the Arctic approaches.46 Canada recently increased its investment in ESA programs to bolster its R&D base.47

- Spain (Rank 15): Spain is modernizing its secure communications with the SpainSat NG (Next Generation) program. SpainSat NG-I, launched in early 2025, provides secure X-band and Ka-band communications for the Spanish Armed Forces and NATO, featuring advanced anti-jamming and anti-spoofing technologies.48

4.2 The “Niche” Specialists

These nations have developed specialized capabilities tailored to their unique security environments, often punching above their weight in specific technologies.

- Israel (Rank 8): Israel occupies a unique position as a space power. It launches its Ofeq reconnaissance satellites westward—against the Earth’s rotation—to avoid flying over hostile Arab neighbors during launch. The Arrow-3 missile defense system, designed to intercept ballistic missiles outside the atmosphere, possesses an inherent, de facto kinetic ASAT capability.32 While primarily defensive, this capability serves as a potent deterrent.

- South Korea (Rank 11): Driven by the existential threat from the North, South Korea has aggressively pursued independent space capabilities. The 425 Project is deploying a constellation of five high-resolution spy satellites (4 SAR, 1 Optical) to monitor North Korean missile sites in near-real-time.51 South Korea established a Space Operations Command and is developing indigenous solid-fuel rockets to reduce reliance on foreign launch providers.52

- Turkey (Rank 16): Turkey has steadily built a sovereign space capability with the Göktürk series of Earth observation satellites. Göktürk-1 provides sub-meter resolution imagery for intelligence and counter-terrorism operations.53 Turkey’s space agency has ambitious goals, including a moon mission, and the military views space assets as critical for its regional power projection.54

- United Arab Emirates (Rank 17): The UAE has emerged as the most advanced Arab space power. The Falcon Eye satellites provide very high-resolution optical imagery for military use.55 The UAE views space not just as a military necessity but as a strategic pillar of its post-oil economy, heavily investing in human spaceflight and planetary exploration to build a knowledge-based sector.56

- Brazil (Rank 19): As the dominant power in South America, Brazil operates the SGDC (Geostationary Defense and Strategic Communications) satellite to secure government communications over its vast territory and the South Atlantic.57 This asset is critical for sovereignty and the integration of remote border regions.

- Saudi Arabia (Rank 20): Saudi Arabia is investing heavily in space through the Saudi Space Agency. The SaudiSat-5A and 5B satellites provide high-resolution imagery for development and security purposes.58 The Kingdom is leveraging partnerships to build a domestic space industry as part of its Vision 2030 modernization plan.59

4.3 The “Asymmetric” Challengers

These nations possess limited but dangerous capabilities. They often rely on “dual-use” technologies and view space as a domain for asymmetric warfare against superior adversaries.

- Iran (Rank 13): Iran’s military space program is run by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), separate from its civilian agency. The Noor series of small military satellites provides a rudimentary reconnaissance capability.60 Of greater concern is the Qased launch vehicle, which uses solid-fuel technology virtually identical to that required for Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs).61 Iran has also demonstrated GPS jamming capabilities.

- North Korea (Rank 14): North Korea successfully placed the Malligyong-1 reconnaissance satellite into orbit in November 2023.62 While its imaging resolution is likely low compared to modern standards, the ability to conduct independent Battle Damage Assessment (BDA) or target U.S. carrier groups fundamentally changes the tactical equation on the Korean peninsula. The regime has threatened to treat any interference with its satellites as a declaration of war.63

5. Future Outlook: The Trend Toward Proliferation

The trajectory of space warfare is defined by two converging trends: Proliferation and Counterspace Normalization.

We are witnessing the end of the “Battlestar Galactica” era—the dominance of massive, monolithic, billion-dollar satellites like the U.S. KH-11. The future belongs to “swarms” and proliferated architectures. The war in Ukraine demonstrated the resilience of Starlink, a commercial mega-constellation that Russian electronic warfare failed to permanently silence. This lesson has been absorbed by all major powers. The U.S., China, and Europe are all rushing to build proliferated LEO architectures that are “anti-fragile”—networks where the loss of any single node is operationally irrelevant.

Simultaneously, capabilities that were once theoretical “doomsday” weapons are becoming standardized parts of military doctrine. As evidenced by the French and Japanese pivots to “Active Defense” and the deployment of jammers by Iran and Russia, the taboo against weaponizing space is eroding. The future will likely see “grey zone” warfare in orbit—dazzling, reversible jamming, and cyber-intrusions—becoming a daily reality of geopolitical competition, blurring the lines between peace and war in the vacuum of space.

Appendix: Methodology

This report employed a multi-source analysis methodology to synthesize the “Top 20” ranking and strategic assessments.

- Snippet Analysis: Information was extracted and synthesized from 318 provided research snippets 1, comprising government policy documents, intelligence reports, industry news, and academic analyses.

- Composite Ranking Metric: The Top 20 ranking was derived not solely from raw satellite counts (which can skew towards commercial-heavy nations) but from a weighted “Space Warfare Capability” score. This score aggregated the following factors:

- Kinetic Potential (30%): Proven ability to destroy or physically disable on-orbit assets (e.g., ASAT tests).

- Electronic/Cyber Warfare (25%): Proven ability to jam, spoof, or hack space links (e.g., GPS jamming, uplink denial).

- Orbital Presence (20%): Number of active military-designated satellites (ISR, Comms, PNT).

- Organizational Maturity (15%): Presence of a dedicated Space Command/Force and articulated military doctrine.

- Budget/Industry (10%): Sustainable funding levels and the existence of an indigenous launch and manufacturing base.

- Data Harmonization: Where snippets provided conflicting data (e.g., specific satellite counts), priority was given to the most recent specialized reports (e.g., Union of Concerned Scientists 2024 database updates) over general news articles.

- Analogical Framework: Strategic analogies were derived directly from the works of space power theorists (Bowen, Mahan, Douhet) referenced in the provided research materials to ensure a grounded theoretical basis.

Data Tables for Visuals

Table 1: Data for Top 20 Matrix (Figure 1)

| Rank | Country | Satellite Count | Kinetic ASAT | EW Capability | Command Structure |

| 1 | USA | 247 | Yes | High | USSF |

| 2 | China | 157 | Yes | High | PLASSF |

| 3 | Russia | 110 | Yes | High | VKS |

| 4 | France | 17 | Dev | Med | CDE |

| 5 | India | 9 | Yes | Low | DSA |

| 6 | Japan | 15 | No | Med | SOG |

| 7 | UK | 6 | No | Med | UKSC |

| 8 | Israel | 12 | Yes* | Med | Sp. Branch |

| 9 | Germany | 8 | No | Med | WRKdo |

| 10 | Italy | 10 | No | Low | COS |

| 11 | S. Korea | 5 | No | Low | Sp. Op. |

| 12 | Australia | 4 | No | Low | DSC |

| 13 | Iran | 3 | No | Med | IRGC |

| 14 | N. Korea | 2 | No | Low | NATA |

| 15 | Spain | 4 | No | Low | SASF |

| 16 | Turkey | 6 | No | Low | TSA |

| 17 | UAE | 3 | No | Low | UAESA |

| 18 | Canada | 4 | No | Low | 3 CSD |

| 19 | Brazil | 1 | No | Low | COPE |

| 20 | Saudi Arabia | 2 | No | Low | SSA |

Table 2: Data for Radar Chart (Figure 3)

| Dimension | USA | China | Russia | France | India |

| Orbital Presence | 10 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| Kinetic Lethality | 8 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 7 |

| Non-Kinetic Cap (EW) | 9 | 9 | 10 | 5 | 3 |

| Org Maturity | 10 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 5 |

| Budget | 10 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- The Advancement of Space Warfare – RMC Global, accessed January 26, 2026, https://rmcglobal.com/the-advancement-of-space-warfare/

- Challenges to Security in Space, accessed January 26, 2026, https://aerospace.csis.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/20190101_ChallengestoSecurityinSpace_DIA.pdf

- Space is ultimate high ground > Air Force > Article Display, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.af.mil/news/article-display/article/139149/space-is-ultimate-high-ground/

- the 21st century revolution in military affairs: space primacy, accessed January 26, 2026, https://nssaspace.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/space-primacy-brown.pdf

- Chapter: 2 Strategic Framework: Future Operational Concepts and Space Needs – National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.nationalacademies.org/read/11299/chapter/4

- Escalation Risks at the Space–Nuclear Nexus – SIPRI, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2024-02/2402_rpp_space-nuclear_nexus.pdf

- War in Space: Strategy, Spacepower, Geopolitics > Air University …, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Aether-ASOR/Book-Reviews/Article/3649189/war-in-space-strategy-spacepower-geopolitics/

- 7 Principles of Space Warfare – Edinburgh University Press Blog, accessed January 26, 2026, https://euppublishingblog.com/2022/02/23/7-principles-of-space-warfare/

- Our Military Space Operations – Ministère des Armées, accessed January 26, 2026, http://www.defense.gouv.fr/en/cde/our-military-space-operations

- Joint Doctrine Publication 0-40 – GOV.UK, accessed January 26, 2026, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/653a5261e6c968000daa9b8a/JDP_0_40_UK_Space_Power_web.pdf

- Counter Communications System | L3Harris® Fast. Forward., accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.l3harris.com/all-capabilities/counter-communications-system

- Counter Communications System Block 10.2 achieves IOC, ready for the warfighter > United States Space Force > News, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.spaceforce.mil/News/article/2113447/counter-communications-system-block-102-achieves-ioc-ready-for-the-warfighter/

- 2025 Global Counterspace Capabilities Report – Secure World Foundation, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.swfound.org/publications-and-reports/2025-global-counterspace-capabilities-report

- Space Technology Trends 2025 | Lockheed Martin, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/news/features/2024/space-technology-trends-2025.html

- The New Era of Space Warfare – Defense Security Monitor, accessed January 26, 2026, https://dsm.forecastinternational.com/2025/09/23/the-new-era-of-space-warfare/

- Space Threat Fact Sheet, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.spaceforce.mil/About-Us/Fact-Sheets/Fact-Sheet-Display/Article/4297159/space-threat-fact-sheet/

- An Interactive Look at the U.S.-China Military Scorecard – RAND, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.rand.org/paf/projects/us-china-scorecard.html

- A review of Chinese counterspace activities – The Space Review, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.thespacereview.com/article/4431/1

- China’s SJ-21 Framed as Demonstrating Growing On-Orbit Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing (OSAM) Capabilities – Air University, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/documents/Research/Space/2021-12-09%20SJ-21%20and%20China’s%20OSAM%20Capabilities.pdf

- China says it has launched a space debris mitigation tech demo satellite – Spaceflight Now, accessed January 26, 2026, https://spaceflightnow.com/2021/10/25/china-says-it-has-launched-a-space-debris-mitigation-tech-demo-satellite/

- Countries By Number Of Military Satellites – World Atlas, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.worldatlas.com/space/countries-by-number-of-military-satellites.html

- Military satellites – TAdviser, accessed January 26, 2026, https://tadviser.com/index.php/Article:Military_satellites

- Space force – Wikipedia, accessed January 26, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Space_force

- ARMS CONTROL TODAY – Sma.nasa.gov., accessed January 26, 2026, https://sma.nasa.gov/SignificantIncidents/assets/armscontroltoday_russianasat.pdf

- Russia conducts direct-ascent anti-satellite test, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.iiss.org/online-analysis/online-analysis/2021/11/russia-conducts-direct-ascent-anti-satellite-test/

- CSIS 2025 Space Threat Assessment: Cyberattacks on space systems persist, tracking harder amid infrastructure threats – Industrial Cyber, accessed January 26, 2026, https://industrialcyber.co/reports/csis-2025-space-threat-assessment-cyberattacks-on-space-systems-persist-tracking-harder-amid-infrastructure-threats/

- Russia Working on New Space-Based Anti-Satellite Capabilities – PISM, accessed January 26, 2026, https://pism.pl/publications/russia-working-on-new-space-based-anti-satellite-capabilities

- France’s Space Command and the Strategic Stakes of Commercial Satellite Warfare, accessed January 26, 2026, https://bisi.org.uk/reports/frances-space-command-and-the-strategic-stakes-of-commercial-satellite-warfare

- Implementing the French Space Defence Strategy: Towards Space Control? :: Note de la FRS :: Foundation for Strategic Research, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.frstrategie.org/en/publications/notes/implementing-french-space-defence-strategy-towards-space-control-2023

- The Evolution of French Space Security, accessed January 26, 2026, http://aerospace.csis.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/240314_Young_French_Space.pdf

- National space strategy 2025 – 2040 – SGDSN, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.sgdsn.gouv.fr/files/files/Publications/National%20space%20strategy%202025%20-%202040.pdf

- New Report Catalogs Military Capabilities in Orbit – Payload Space, accessed January 26, 2026, https://payloadspace.com/secure-world-foundation-catalogs-global-space-military-capabilities/

- Military Satellites by Country 2026 – World Population Review, accessed January 26, 2026, https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/military-satellite-by-country

- Pakistan’s Need For Defensive Space Capabilities – The Defence Horizon Journal, accessed January 26, 2026, https://tdhj.org/blog/post/pakistan-space-capabilities/

- “Pakistan’s Space Program: From Sounding Rockets to Satellite Setbacks” by Sannia Abdullah – DigitalCommons@UNO, accessed January 26, 2026, https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/spaceanddefense/vol12/iss3/5/

- SPECIAL FEATURE | JDF – Japan Defense Focus (No.125), accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.mod.go.jp/en/jdf/no125/specialfeature.html

- Japan boosts defense satellite investments to strengthen space resilience, communications, accessed January 26, 2026, https://ipdefenseforum.com/2025/02/japan-boosts-defense-satellite-investments-to-strengthen-space-resilience-communications/

- Japan Ministry of Defense Unveils Record High FY 2025 Budget Request – USNI News, accessed January 26, 2026, https://news.usni.org/2024/09/04/japan-ministry-of-defense-unveils-record-high-fy-2025-budget-request

- The UK Defence Space Strategy | Royal United Services Institute – RUSI, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/uk-defence-space-strategy

- Space Component Command – Bundeswehr, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.bundeswehr.de/en/organization/german-air-force/organization/space-component-command-

- Germany’s first space security strategy aims at independent defensive, offensive capabilities, accessed January 26, 2026, https://breakingdefense.com/2025/11/germanys-first-space-security-strategy-aims-at-independent-defensive-offensive-capabilities/

- Reach for the Stars: Bridging Italy’s Potential in Space with Its Foreign and Security Policy, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.iai.it/en/publications/c05/reach-stars-bridging-italys-potential-space-its-foreign-and-security-policy

- MILITARY SATELLITE COMMUNICATIONS – Telespazio, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.telespazio.com/documents/559023/8275902/MILSATCOM_ENG_072016.pdf?t=1561108269814

- Australia kills $5.3B military space program with Lockheed – Breaking Defense, accessed January 26, 2026, https://breakingdefense.com/2024/11/australia-kills-5-3b-military-space-program-with-lockheed/

- Australian Space Command considers ‘space control’ options: Senior officer, accessed January 26, 2026, https://breakingdefense.com/2025/10/australian-space-command-considers-space-control-options-senior-officer/

- Chapter 4: Protecting Canada’s sovereignty and security | Budget 2025, accessed January 26, 2026, https://budget.canada.ca/2025/report-rapport/chap4-en.html

- Canada Deepens Space Ties with Europe Through Historic Investment, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.canada.ca/en/space-agency/news/2025/11/canada-deepens-space-ties-with-europe-through-historic-investment.html

- Airbus-built SpainSat NG-I satellite successfully launched, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.airbus.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2025-01-airbus-built-spainsat-ng-i-satellite-successfully-launched

- SPAINSAT NG Program – hisdesat.es, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.hisdesat.es/en/s-communications/spainsat-ng-program/

- Arrow (missile family) – Wikipedia, accessed January 26, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arrow_(missile_family)

- South Korea’s Fifth Satellite Enters Orbit, Boosting North Korea Surveillance, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.chosun.com/english/national-en/2025/11/02/DDVFGHWSJVELRC2PZHZE3LDJLA/

- Space Forces – Korea stands up first forward operating CJSpOC in support of FS25, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.safia.hq.af.mil/IA-News/Article/4132492/space-forces-korea-stands-up-first-forward-operating-cjspoc-in-support-of-fs25/

- Gokturk-1 Imaging Mission, Turkey – eoPortal, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.eoportal.org/satellite-missions/gokturk-1

- Turkey’s eyes in space – Türksat, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.turksat.com.tr/en/haberler/turkeys-eyes-space

- Launch success for UAE’s FalconEye satellite | Thales Group, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.thalesgroup.com/en/news-centre/press-releases/launch-success-uaes-falconeye-satellite

- UAE shaping future of Earth observation, satellites and space exploration, accessed January 26, 2026, https://space.gov.ae/en/media-center/blogs/2/3/2020/uae-shaping-future-of-earth-observation-satellites-and-space-exploration

- Geostationary Satellite for Defense and Strategic Communications – Wikipedia, accessed January 26, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geostationary_Satellite_for_Defense_and_Strategic_Communications

- SaudiSat 5A,5B – Wikipedia, accessed January 26, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SaudiSat_5A,5B

- Middle East Embraces Space Race, accessed January 26, 2026, https://spaceproject.govexec.com/defense/2024/10/middle-east-embraces-space-race/400189/

- Noor (satellite) – Wikipedia, accessed January 26, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Noor_(satellite)

- Iran Launches Satellite Using Ballistic Missile Technology – FDD, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.fdd.org/analysis/2023/09/29/iran-launches-satellite-using-ballistic-missile-technology/

- Malligyong-1 – Wikipedia, accessed January 26, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malligyong-1

- The Korean Space Race – Lieber Institute – West Point, accessed January 26, 2026, https://lieber.westpoint.edu/korean-space-race/

- Thales Alenia Space strengthens Spanish space industry leadership through its participation in SpainSat NG II satellite, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.thalesaleniaspace.com/en/press-releases/thales-alenia-space-strengthens-spanish-space-industry-leadership-through-its