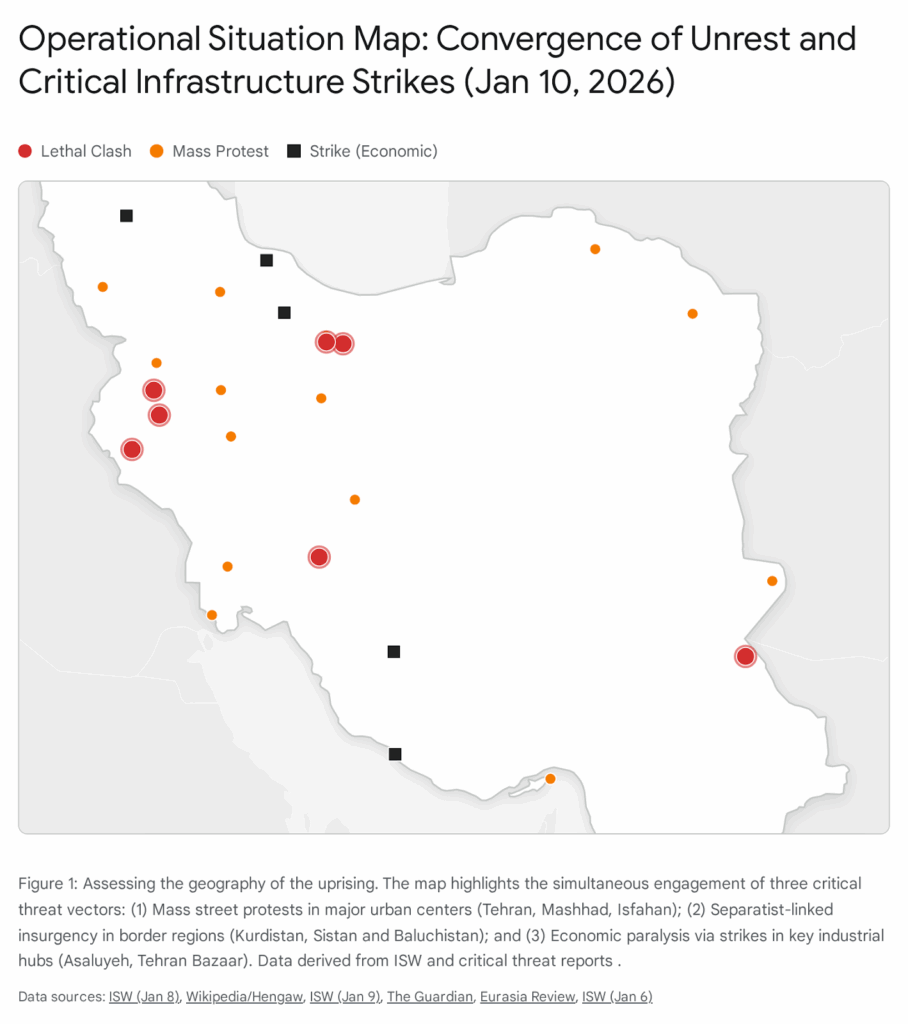

Date: January 10, 2026

Subject: Assessment of Nationwide Unrest, Regime Stability, and Strategic Outlook for the Islamic Republic of Iran

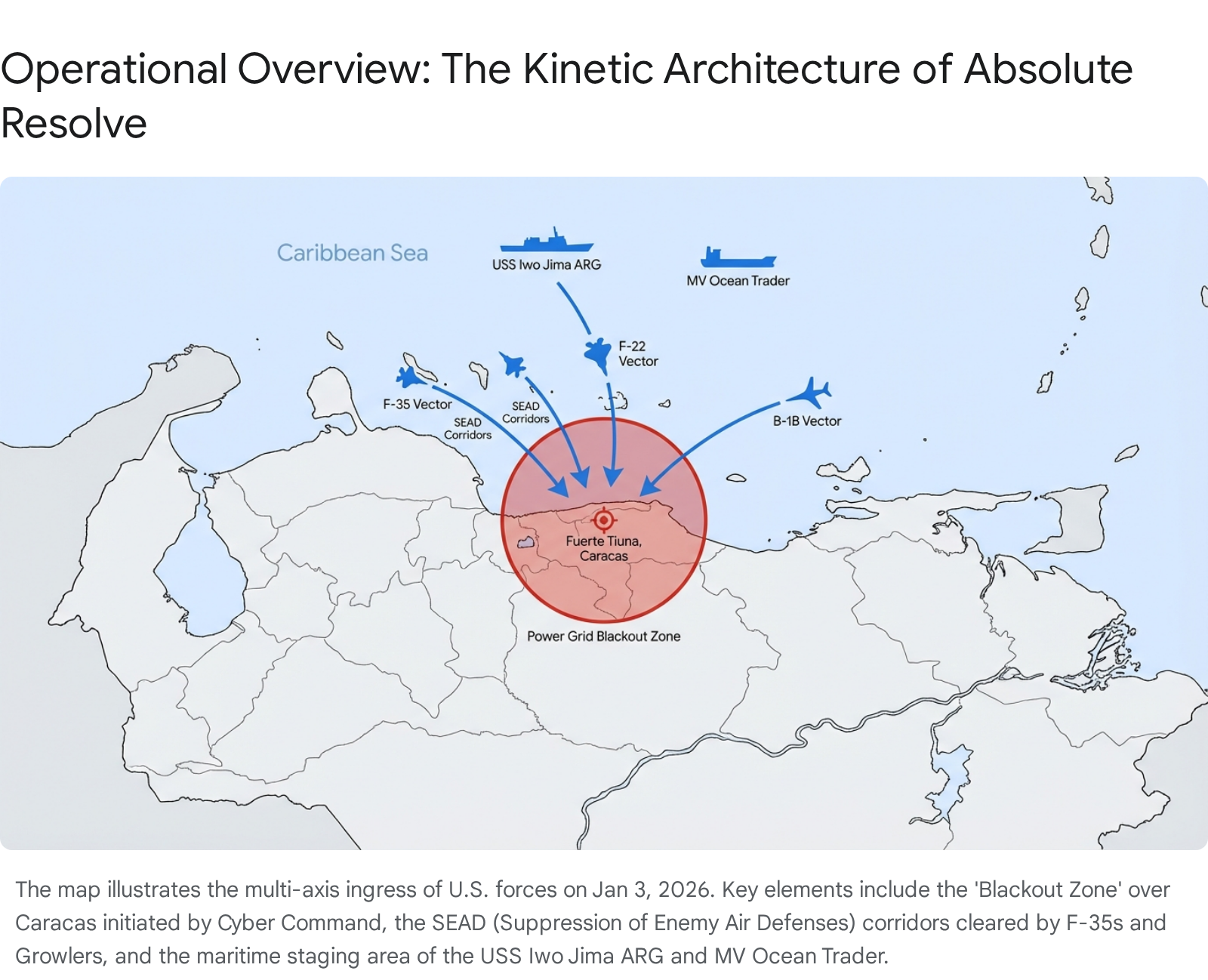

The Islamic Republic of Iran is currently navigating the most precarious existential crisis in its forty-seven-year history, a convergence of catastrophic economic failure, the geopolitical aftershocks of the “Twelve-Day War” of June 2025, and a nationwide uprising of unprecedented scope and intensity. As of January 10, 2026, the clerical regime faces a “dual-pressure” dynamic that it has successfully avoided in previous cycles of unrest: mass street mobilization coinciding with crippling labor strikes in critical economic sectors, specifically the bazaar and the hydrocarbon industry.

The unrest, triggered on December 28, 2025, by a sudden hyperinflationary spike and the collapse of the Rial, has rapidly metamorphosed from an economic grievance movement into a revolutionary demand for the end of the theocratic system. Unlike the protests of 2009, 2017, 2019, or 2022, the current uprising is characterized by a “swarm intelligence” tactical capability among protesters and a distinct erosion of the regime’s “fear barrier.”

Key Findings:

- Regime Survival is at Critical Risk: The probability of regime collapse or fundamental transformation within the next 6-12 months is assessed at High. The synergy between street mobilization and labor strikes—specifically in the South Pars energy sector and major bazaars—replicates the structural conditions that led to the 1979 revolution.

- Security Apparatus Strain and Fracture: While the core of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) remains cohesive, signs of exhaustion and localized insubordination have emerged within the Law Enforcement Command (LEC) and ground forces. The regime’s reliance on lethal force—resulting in at least 217 deaths in Tehran alone—has failed to quell the unrest, necessitating the deployment of military assets to manage civil disturbances, a clear indicator of police overstretch.

- Leadership Vacuum and Bunker Mentality: Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, aged 86, is operating from a secure bunker following Israeli strikes in 2025. His recent move to designate three potential successors—reportedly excluding his son Mojtaba—suggests acute anxiety regarding continuity and internal factionalism. The executive branch, led by President Masoud Pezeshkian, has been rendered effectively powerless, unable to bridge the gap between the street and the deep state.

- Economic Irreversibility: With the Rial trading at approximately 1.47 million to the US Dollar and inflation exceeding 50%, the government lacks the fiscal capacity to buy public quiescence. The destruction of sanctions-evasion networks during the 2025 conflict and the renewed “Maximum Pressure” campaign have severed the regime’s financial arteries.

This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the operational, economic, and political vectors driving this crisis, offering detailed prognoses for the immediate and short term.

1. Strategic Context: The “Perfect Storm” of 2025-2026

To fully comprehend the volatility of the operational environment in January 2026, one must analyze the antecedent events of 2025 that dismantled the regime’s traditional survival mechanisms. The current uprising is not an isolated stochastic event but the culmination of a systematic degradation of state power and legitimacy.

1.1 The Operational Legacy of “Rising Lion” (June 2025)

In June 2025, the long-simmering shadow war between Iran and Israel escalated into a direct, high-intensity conflict known as “Operation Rising Lion”.1 This 12-day war fundamentally altered the balance of power in the Middle East and stripped Tehran of its primary strategic deterrents.

Nuclear Degradation:

Intelligence assessments confirm that joint Israeli and US operations “effectively destroyed” Iran’s uranium enrichment capacity and targeted key nuclear scientists.2 The strikes on facilities such as Natanz and Fordow utilized advanced penetrator munitions, causing extensive structural damage to underground complexes.1 This decapitation of the nuclear program removed the regime’s ultimate bargaining chip with the West, leaving it strategically exposed without the leverage of a “breakout” threat.

Conventional Defeat and Air Defense Collapse:

The Israeli Air Force (IAF) established total air superiority during the campaign, destroying over 70% of Iran’s missile launchers and creating a critical bottleneck in missile production.4 The systematic dismantling of Iran’s integrated air defense system (IADS) has left the regime psychologically naked. The destruction of S-300 and other advanced surface-to-air missile batteries forced the senior leadership, including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, into deep bunkers, where they reportedly remain.5 This physical isolation has severed the visible link between the leadership and the populace, reinforcing the image of a regime under siege.

Proxy Network Disintegration:

The “Axis of Resistance”—Iran’s “forward defense” doctrine—has suffered catastrophic degradation. Hezbollah in Lebanon and various militia groups in Syria and Iraq were decimated during the regional conflicts of 2024-2025. By January 2026, these groups are fighting for their own survival and are operationally unable to deploy effectively to suppress Iranian domestic unrest, a tactic the regime had utilized in previous crackdowns.6 The absence of these foreign fighters removes a critical layer of the regime’s repressive redundancy.

1.2 The Economic Precipice and “Maximum Pressure 2.0”

The military defeat was immediately compounded by a renewed economic strangulation. Following the “snapback” of UN sanctions in September 2025, the second Trump administration initiated “Maximum Pressure 2.0” in January 2025.7

Hyperinflation and Currency Collapse:

By late 2025, the Iranian Rial (IRR) had collapsed to approximately 1.47 million against the US Dollar, a historic low.7 This devaluation obliterated the purchasing power of the middle class and the Mustazafin (oppressed)—the regime’s traditional base of support. Inflation rates for food and basic goods skyrocketed to over 70% year-on-year 10, creating a situation where millions of Iranians are facing genuine malnutrition and food insecurity.

Systemic Energy Crisis:

Despite being an energy superpower, Iran faces acute domestic shortages of natural gas and electricity. Strikes on infrastructure during the war, combined with decades of mismanagement and lack of investment, have crippled the energy sector. This has resulted in rolling blackouts and heating shortages during the winter of 2025-2026, further inflaming public anger and halting industrial production.7 The regime’s inability to provide basic utilities has shattered the “social contract” of subsidized stability.

2. Operational Analysis of the Uprising (January 2026)

The current wave of protests, which began on December 28, 2025, is distinct from previous rounds in its velocity, demographic breadth, and tactical sophistication. It represents a “total war” by the populace against the state apparatus.

2.1 Timeline of Escalation

The trajectory of the uprising indicates a rapid loss of state control over the street and a collapsing “escalation ladder” for the regime.

Phase 1: Economic Trigger (Dec 28 – Dec 30):

Protests began in the Grand Bazaar of Tehran—the historical heart of Iran’s conservative merchant class. Shopkeepers struck against the currency collapse and the soaring cost of imports. This was a critical signal; the Bazaaris have historically been a pillar of the clerical establishment. Their turn against the regime signifies that the clergy has lost its financial theology. Initially, the demands were economic, focused on the exchange rate and inflation.11

Phase 2: Radicalization and Expansion (Dec 31 – Jan 7):

The movement rapidly expanded beyond the merchant class. University students and youth in peripheral provinces joined the fray. Slogans shifted immediately from “Death to High Prices” to “Death to Dictator,” “Death to Khamenei,” and “Seyyed Ali [Khamenei] will be toppled this year”.11 By January 7, protests had spread to 31 provinces and over 156 locations, including religiously conservative strongholds like Qom and Mashhad.8

Phase 3: The General Strike and Blackout (Jan 8 – Present):

Following a call by exiled Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi and a coalition of Kurdish opposition parties, a general strike paralyzed the country on January 8. The regime responded with a total internet blackout, reducing connectivity to approximately 1%.13 This phase has seen the highest levels of violence, with security forces utilizing heavy machine guns and live ammunition in multiple cities.

2.2 Geography of Resistance

The Center (Tehran, Isfahan, Karaj):

Large-scale urban warfare is reported in the capital and its satellites. In Tehran, the sheer density of protests has overwhelmed the Law Enforcement Command (LEC), forcing the deployment of the IRGC Ground Forces.11 Protesters have burned government buildings, including an IRIB (state broadcaster) facility in Esfahan, demonstrating a willingness to target the regime’s propaganda organs.13

The Periphery (Kurdistan, Baluchistan):

In the west (Sanandaj, Kermanshah) and southeast (Zahedan), the uprising resembles an armed insurgency. Kurdish opposition groups (KDPI, Komala, PJAK) have mobilized, and the regime is treating these areas as combat zones, using heavy weaponry and deploying military units rather than riot police.12 In Zahedan, the weekly Friday protests have resumed with renewed intensity following sermons by Sunni cleric Moulana Abdol Hamid, who has declared the crackdown a “crime under international law”.13

The “Tank Man” Phenomenon:

Symbolic acts of defiance have shattered the aura of regime invincibility. Viral footage—circulated before the blackout—showed individuals blocking security vehicles in Tehran’s Jomhuri Eslami Street, reminiscent of Tiananmen Square.11 These images have galvanized the public, proving that the security forces can be defied.

2.3 Tactics and Organization

While the movement is often described as “leaderless,” it exhibits a sophisticated “swarm intelligence.” Protesters utilize small, mobile groups to exhaust security forces, retreating and regrouping rapidly in different neighborhoods to stretch police resources thin.

Self-Defense and Counter-Aggression:

Unlike the protests of 2009, protesters are actively fighting back. Reports indicate attacks on Basij bases, the burning of regime symbols (including statues of Qassem Soleimani), and the temporary seizure of government buildings in smaller towns like Abdanan.16 The barrier of fear has eroded; protesters are no longer fleeing from gunfire but are standing their ground or engaging in hit-and-run attacks on security personnel.

3. The Economic War: Strikes and Sanctions

The most dangerous development for the regime is the fusion of street protests with labor strikes. The 1979 revolution succeeded not because of street marches alone, but because the oil workers turned off the taps, bankrupting the Shah. A similar dynamic is unfolding in January 2026.

3.1 The Energy Sector Strike

Reports from January 7-9 confirm that strikes have spread to the strategic South Pars gas field and refineries in Abadan and Asaluyeh.17 This is a critical escalation.

Strategic Impact:

The oil and gas sector provides the vast majority of the government’s hard currency revenue. A sustained strike here serves a dual purpose: it bankrupts the state—already reeling from sanctions—and cuts off domestic fuel supplies, paralyzing logistics and transportation. The “Coordination Council for Protests of Contract Oil Workers” has been instrumental in organizing these actions, linking labor demands with the broader political uprising.11

The “Teapot” Dilemma:

China, the primary buyer of Iranian illicit oil, is facing supply disruptions. With Venezuelan supply also uncertain due to recent US interventions, Iran’s inability to export due to strikes would sever its last major diplomatic and economic lifeline.19 This loss of revenue renders the regime unable to pay the wages of the very security forces it relies on to crush the protests.

3.2 The Bazaar and Commercial Sector

The strikes in the Grand Bazaar of Tehran, Tabriz, Rasht, and Isfahan are symbolic and functional death knells for the regime’s domestic legitimacy.17 The closure of the bazaar is not merely an economic halt; it is a political withdrawal of support by the conservative middle class. The “Bazaari-Clergy Alliance,” a cornerstone of the 1979 revolution, has effectively dissolved. The bazaaris are now aligning with the “Generation Z” protesters, creating a cross-class coalition that the regime cannot easily divide.

3.3 Macroeconomic Collapse Indicators

The economic engine of the protests is the chaotic devaluation of the national currency. The correlation between the Rial’s value and protest intensity is direct and causal.

- Currency Devaluation: The Rial, which traded at ~500,000 to the USD in early 2024, has depreciated to ~1.47 million.7 This collapse was triggered by the “Maximum Pressure” signals and the regime’s loss of access to foreign reserves.

- Inflationary Spiral: Inflation has exceeded 50%, with food inflation significantly higher at over 70%.10 This has driven the “grey” population—those who previously stayed home due to apathy or fear—onto the streets out of sheer desperation.

- Unemployment: The unemployment rate stands at 9.2% officially, but youth unemployment is estimated to be significantly higher, fueling the recruitment of young men into the protest movement.20

Table 1: Key Economic Indicators (January 2026)

| Indicator | Value | Trend | Strategic Implication |

| USD/IRR Exchange Rate | ~1,470,000 | Collapsing | Erases savings; destroys middle-class wealth. |

| Annual Inflation | 52.6% | Accelerating | Makes basic staples unaffordable; fuels rage. |

| Food Inflation | >72% | Critical | Direct driver of participation by lower classes. |

| GDP Growth (Non-Oil) | -0.8% | Contracting | Indicates deep recession in the real economy. |

| Oil Production | Disrupted | Volatile | Strike action threatens state revenue solvency. |

| Unemployment | 9.2% (Official) | Rising | Provides manpower for street mobilization. |

Sources: IMF 20, Trading Economics 21, Central Bank of Iran 10

4. Regime Cohesion and Security Apparatus: The Breaking Point?

The ability of the Islamic Republic to survive depends entirely on the cohesion of its coercive apparatus: the IRGC, the Basij, and the Law Enforcement Command (LEC). Current intelligence suggests unprecedented strain and the beginning of fractures.

4.1 Force Exhaustion and Bandwidth Constraints

The regime is suffering from a “bandwidth” crisis. The simultaneous eruption of protests in 156+ locations prevents the concentration of forces—a tactic used successfully in 2019 and 2022 to crush unrest city by city.12

LEC Overstretch:

The regular police (LEC) have proven incapable of containing the crowds. In cities like Eslamabad-e Gharb and Bushehr, security forces reportedly retreated or fled due to being outnumbered.13 This loss of control forces the regime to deploy the IRGC Ground Forces, a move that signals the failure of the primary internal security layer.

IRGC Deployment and Attrition:

The deployment of the IRGC Ground Forces (e.g., the Nabi Akram Unit in Kermanshah) indicates that the situation is viewed as an insurgency rather than a riot. However, even elite units are taking casualties; the Nabi Akram unit reportedly lost at least 10 members in clashes.13 The death of IRGC soldiers implies that protesters are either armed or using lethal improvised tactics, forcing the IRGC into a kill-or-be-killed dynamic that degrades morale.

4.2 Signs of Fracture and Insubordination

For the first time in recent memory, credible reports of insubordination have emerged from within the security apparatus.

Refusals to Fire:

Human rights organizations have documented instances of security personnel refusing orders to fire on crowds. The regime has reportedly arrested several security force members for disobedience.14 This is the “nightmare scenario” for the leadership: a mutiny within the ranks. If the conscript-heavy army (Artesh) or even elements of the IRGC refuse to slaughter civilians, the regime’s coercive capacity evaporates.

Judicial Threats and Desperation:

The judiciary has resorted to extreme threats, announcing that protesters using weapons will be charged with moharebeh (“enmity against God”), a crime punishable by death.13 This legal escalation is intended to terrify the populace, but given the scale of the unrest, mass executions may only serve to further radicalize the opposition.

4.3 Structural Health of the Regime Pillars

The stability of the Islamic Republic has historically rested on five pillars. An assessment of their current status reveals a regime in structural collapse.

1. Ideological Legitimacy (Collapsed): The concept of Velayat-e Faqih (Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist) has lost all traction with the youth and the broader public. Slogans attacking the Supreme Leader directly indicate a total rejection of the theological basis of the state.

2. Economic Patronage (Collapsed): The regime can no longer afford to subsidize its supporters. The collapse of the Rial and the bankruptcy of the state mean that the patronage network—which kept the rural poor loyal—is broken.

3. The Bazaar/Merchant Class (Fractured/Opposed): As detailed in Section 3.2, the bazaar has turned against the state, severing a critical alliance.

4. External Proxies (Degraded): The “Axis of Resistance” is shattered. Hezbollah and Iraqi militias are fighting for their own survival and cannot provide reinforcements to Tehran.6

5. Coercive Apparatus (Strained but Holding): This is the only remaining pillar. The IRGC’s elite core remains loyal due to ideological indoctrination and financial interest, but the rank-and-file are wavering. If this pillar cracks, the regime falls.

5. Political Paralysis and the Succession Crisis

As the streets burn, the regime’s leadership is paralyzed by an internal crisis of succession and physical insecurity.

5.1 The “Bunker” Mentality and Leadership Isolation

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei is reportedly operating from a secure underground location (bunker) in Lavizan or near Tehran, a measure taken during the June 2025 war and maintained due to fears of Israeli assassination.5

- Operational Impact: This physical isolation limits his ability to project control and signals fear to the lower ranks of the bureaucracy. A leader in hiding cannot effectively rally his base.

- Communication Breakdown: Reports indicate that Khamenei has suspended the use of electronic devices and communicates only through trusted aides, slowing down the decision-making loop during a fast-moving crisis.5

5.2 The Succession Leak and Mojtaba’s Exclusion

In an unprecedented development, Khamenei has reportedly designated three potential successors to ensure continuity if he is killed. Crucially, reports indicate that his son, Mojtaba Khamenei, was excluded from this emergency list, or at least sidelined in the immediate “war planning” scenario.22

- The Candidates: The three named clerics are likely senior figures such as Alireza Arafi, Hashem Hosseini Bushehri, or Muhammad Mirbaqiri.23

- Analysis: The exclusion of Mojtaba, previously seen as the front-runner, suggests a concession to the IRGC top brass or internal clerical factions who view a hereditary succession as a liability that could spark immediate revolt. Alternatively, it may be a deception plan. Regardless, the leak of such sensitive information indicates deep fissures within the intelligence apparatus.

5.3 The Irrelevance of President Pezeshkian

President Masoud Pezeshkian, elected in 2024 on a reformist ticket, has been rendered totally ineffective. His campaign promises to lift internet censorship and improve the economy have evaporated.

- Rhetorical Weakness: His calls for “restraint” and “dialogue” 25 are ignored by both the protesters (who chant for the fall of the system) and the hardline security core (who are shooting to kill). He is effectively a spectator in his own government, blaming parliament for the crisis while the IRGC dictates policy.27

- Political Suicide: By failing to side with the protesters or effectively manage the economy, Pezeshkian has burned his bridges with the reformist electorate, leaving him with no constituency.

6. The Opposition and Alternative Futures

The opposition landscape has evolved from fragmented dissent to a more coalesced, albeit still loose, revolutionary front.

6.1 The “Leaderless” Myth and Coordination

While often described as leaderless, the movement has symbolic leadership and operational coordination.

- Reza Pahlavi: The exiled Crown Prince holds significant symbolic prominence. His call for a general strike on January 8 was widely heeded, demonstrating his ability to mobilize the street and the bazaar simultaneously.11 Slogans praising the Pahlavi dynasty are common, reflecting a nostalgia for a pre-theocratic era.

- The Transition Council: There are emerging reports and rumors of a “Transition Council” being formed, potentially involving opposition figures, labor leaders, and defecting officials. While not formally announced as a government-in-exile, the coordination between Kurdish groups, labor unions, and the diaspora suggests a nascent political structure.29

6.2 Ethnic Insurgencies

The peripheral provinces are acting as the vanguard of the revolution.

- Kurdish Unity: A coalition of seven Kurdish organizations (including KDPI and Komala) called for the general strike, showing a high degree of political maturity and unity.14 Their ability to sustain armed resistance in the Zagros mountains stretches the IRGC’s military capacity.

- Baloch Resistance: In the southeast, the “Mobarizoun Popular Front” (MPF) has escalated attacks on security forces, declaring a state of war in response to the crackdown.30 This opens a second front that the regime cannot ignore.

7. International Dimensions: External Pressure

The external environment is maximally hostile, denying the regime any diplomatic off-ramps or financial relief.

7.1 US Policy: “Maximum Pressure 2.0”

The Trump administration has adopted an aggressive posture, explicitly supporting the protesters and threatening kinetic consequences for a massacre.

- Direct Threats: President Trump has warned that the US will “hit them very hard” if protesters are killed, stating “we are locked and loaded”.31 This deters the regime from using air power or heavy artillery against urban centers.

- Sanctions Tightening: The US Treasury continues to designate individuals and entities involved in sanctions evasion, tightening the noose around the regime’s remaining revenue streams.33

7.2 The European and Global Stance

The European Union and Canada have strongly condemned the violence, calling for an end to the crackdown.35 More importantly, the lack of any European attempt to mediate or offer a financial lifeline (unlike in previous years) signals that the West views the regime as terminal.

8. Prognosis and Scenarios

Based on the convergence of operational, economic, and political factors, the following scenarios are assessed for the immediate (1-4 weeks) and short term (1-6 months).

8.1 Scenario A: The Crackdown Succeeds (Low Probability)

Mechanism: The regime unleashes maximum lethal force (Tiananmen style), killing thousands. The IRGC remains 100% cohesive. The internet blackout effectively breaks the coordination of the strikes.

Why Unlikely: The sheer geographic spread (156 cities) and the “dual pressure” of strikes make this difficult. Killing thousands would likely trigger the final rupture of the army/IRGC rank-and-file. The economy would continue to collapse, leading to a resurgence of unrest within months. The regime lacks the financial resources to sustain a massive deployment indefinitely.

8.2 Scenario B: Fractured Collapse / Military Coup (Medium Probability)

Mechanism: Facing the choice between firing on their own people or losing the country, elements of the IRGC and Army refuse orders or turn on the clerical leadership.

Outcome: The IRGC pushes the Clergy aside, establishing a secular military dictatorship to “save the nation” and negotiate with the West. This would likely involve the removal of Khamenei or his successors.

Indicators: Reports of IRGC infighting, high-level defections, or a sudden change in state media tone regarding the Supreme Leader.

8.3 Scenario C: Revolutionary Overthrow (Medium-High Probability)

Mechanism: The General Strike deepens. Oil production hits zero. The Rial becomes worthless. The security forces, unpaid and exhausted, melt away or defect. Protesters seize critical government buildings in Tehran.

Outcome: The collapse of the Islamic Republic. A chaotic transition period ensues, involving a provisional council including opposition figures (Pahlavi), labor leaders, and representatives from the security forces who defected.

Immediate Prognosis (Next 2 Weeks)

Expect violence to peak. The regime will utilize its remaining loyal units to conduct localized massacres in an attempt to break the momentum. The internet blackout will persist. The critical variable to watch is the oil sector. If the strikes in Asaluyeh and Abadan sustain for another week, the regime’s cash flow will effectively terminate, accelerating the collapse of the security forces’ loyalty. The regime is currently fighting a losing battle against time, economics, and its own people.

Conclusion:

The Islamic Republic is in the terminal phase of its current iteration. It can no longer govern through consent or economic distribution, and its capacity to govern through fear is eroding by the hour. Unless it can reverse the economic collapse—an impossibility under current sanctions—the regime will likely be forced out or fundamentally transformed within the year.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Main header image was computer generated based on reports.

Works cited

- Post-Attack Assessment of the First 12 Days of Israeli and U.S. Strikes on Iranian Nuclear Facilities | ISIS Reports | Institute For Science And International Security, accessed January 10, 2026, https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/post-attack-assessment-of-the-first-12-days-of-israeli-strikes-on-iranian-nuclear-facilities

- Iran Update Special Report, June 24, 2025, Evening Edition | ISW, accessed January 10, 2026, https://understandingwar.org/research/middle-east/iran-update-special-report-june-24-2025-evening-edition/

- № 4 (6), 2025. US Strikes on Iran: Timeline and OSINT Damage Assessment – PIR Center, accessed January 10, 2026, https://pircenter.org/en/editions/%E2%84%96-4-6-2025-us-strikes-on-iran-timeline-and-osint-damage-assessment/

- Operation Rising Lion: Achievements, Open Questions, and Future Scenarios – INSS, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.inss.org.il/publication/rising-lion-analysis/

- Iran’s Khamenei said to pick three potential successors as he hides in bunker, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.timesofisrael.com/khamenei-said-to-pick-three-potential-successors-as-he-hides-in-bunker/

- What to know about the intensifying protests shaking Iran and putting pressure on its theocracy, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/what-to-know-about-the-intensifying-protests-shaking-iran-and-putting-pressure-on-its-theocracy

- INSIGHT: Gas shortage forces Iran plant shutdowns amid economic protests – ICIS, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.icis.com/explore/resources/news/2026/01/08/11169675/insight-gas-shortage-forces-iran-plant-shutdowns-amid-economic-protests/

- Iran: What challenges face the country in 2026?, accessed January 10, 2026, https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-10456/

- Iranian economic crisis – Wikipedia, accessed January 10, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iranian_economic_crisis

- Iran economy contracts despite modest oil growth as inflation and rial slide, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.iranintl.com/en/202512280124

- 2025–2026 Iranian protests – Wikipedia, accessed January 10, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2025%E2%80%932026_Iranian_protests

- Iran Update, January 8, 2026, accessed January 10, 2026, https://understandingwar.org/research/middle-east/iran-update-january-8-2026/

- Iran Update, January 9, 2026 | ISW, accessed January 10, 2026, https://understandingwar.org/research/middle-east/iran-update-january-9-2026/

- Iran Update, January 8, 2026, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/iran-update-january-8-2026

- Iran Update, January 6, 2026 | ISW – Institute for the Study of War, accessed January 10, 2026, https://understandingwar.org/research/middle-east/iran-update-january-6-2026/

- Iran plunged into internet blackout as protests over economy spread nationwide, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/08/iran-plunged-into-internet-blackout-as-protests-over-economy-spread-nationwide

- Day 11 Of Iran Uprising: Strikes Paralyze Shiraz, Tehran, And Kermanshah Markets – OpEd, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.eurasiareview.com/08012026-day-11-of-iran-uprising-strikes-paralyze-shiraz-tehran-and-kermanshah-markets-oped/

- Workers join strike at South Pars refinery in southern Iran, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.iranintl.com/en/202601072515

- Iranian oil will make up for China’s loss of Venezuelan supply – Reuters | Iran International, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.iranintl.com/en/202601076231

- Iran – IMF DataMapper, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/profile/IRN

- Iran Indicators – Trading Economics, accessed January 10, 2026, https://tradingeconomics.com/iran/indicators

- Khamenei picks possible successors amid war, son Mojtaba not among them – NYT, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.iranintl.com/en/202506218672

- Who are Khamenei’s likely successors? | Iran International, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.iranintl.com/en/202411172359

- Next Supreme Leader of Iran election – Wikipedia, accessed January 10, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Next_Supreme_Leader_of_Iran_election

- Iran president calls for ‘utmost restraint’ in handling protests, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.timesofisrael.com/liveblog_entry/iran-president-calls-for-utmost-restraint-in-handling-protests/

- Iranian President calls for restraint in dealing with protesters, accessed January 10, 2026, https://thenewregion.com/posts/4213/iranian-president-calls-for-restraint-in-dealing-with-protesters

- UK lawmaker cites reports on Russian flights to Iran, gold airlift | Iran International, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.iranintl.com/en/202601088798

- Protests erupt in Iran’s capital after exiled prince’s call; internet cuts out soon after, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.mprnews.org/story/2026/01/08/iran-protests-tehran-exiled-prince-internet-shutdown

- What to watch as anti-regime protests engulf Iran – Atlantic Council, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/dispatches/what-to-watch-as-anti-regime-protests-engulf-iran/

- Iran Update, January 7, 2026 | ISW – Institute for the Study of War, accessed January 10, 2026, https://understandingwar.org/research/middle-east/iran-update-january-7-2026/

- Trump threatens Greenland and Iran at meeting with oil bosses on Venezuela – as it happened, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/live/2026/jan/09/trump-venezuela-oil-attacks-minnesota-portland-ice-supreme-court-tariffs-latest-news-updates

- A timeline of how the protests in Iran unfolded and grew, accessed January 10, 2026, https://apnews.com/article/iran-protests-us-israel-war-economy-d5da3b5f56449dd3871c9438c07f069f

- Iran-related Designations | Office of Foreign Assets Control, accessed January 10, 2026, https://ofac.treasury.gov/recent-actions/20250807

- Treasury Targets Iran-Venezuela Weapons Trade, accessed January 10, 2026, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sb0347

- Joint statement on the situation in Iran, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.canada.ca/en/global-affairs/news/2026/01/joint-statement-on-the-situation-in-iran.html

- New wave of protests (and repression) in Iran. The EU stands with the demonstrators, accessed January 10, 2026, https://www.eunews.it/en/2026/01/09/new-wave-of-protests-and-repression-in-iran-the-eu-stands-with-the-demonstrators/