In the contemporary battlespace, the capacity to deliver kinetic energy precisely and effectively at extended ranges constitutes a definitive tactical advantage. The evolution of small arms ammunition has historically been driven by a dialectic between two opposing requirements: the need for anti-materiel destructive power, traditionally the domain of heavy machine guns, and the need for anti-personnel precision, the purview of specialized sniper systems. This report provides an exhaustive technical analysis of the ballistic performance—specifically kinetic energy retention—of four seminal cartridges that define the upper echelon of modern man-portable firepower: the Russian 12.7x108mm (specifically the 7N34 Sniper loading), the NATO .50 BMG (M33 Ball), the .338 Lapua Magnum (250gr), and the .338 Norma Magnum (250gr).

The objective of this analysis is to delineate the performance envelopes of these cartridges to support procurement decisions, systems engineering evaluations, and tactical efficacy studies. While muzzle energy figures are often cited in marketing literature, they are a poor predictor of long-range performance. The true measure of a cartridge’s worth in the anti-materiel and long-range interdiction roles is Energy Retention—the ability of a projectile to resist atmospheric drag and deliver a lethal or disabling blow at distances exceeding 1,500 meters.

This investigation highlights a distinct bifurcation in ballistic philosophy. On one side stands the 12.7mm class, represented by the Eastern 12.7x108mm and Western 12.7x99mm (.50 BMG). These cartridges rely on sheer projectile mass and volume to effect target destruction. On the other side is the .338 caliber class, a bridge between standard infantry rifles and heavy ordnance, designed to extend the effective range of the individual marksman without the logistical burden of the heavier systems.

The following analysis is grounded in a rigorous examination of physical parameters—mass, velocity, ballistic coefficients, and drag models—normalized to Standard Atmospheric Conditions (ICAO) to ensure direct comparability. By dissecting the external ballistics of the 7N34, M33, and the two .338 Magnums, this report reveals that while the .338 class offers exceptional trajectory characteristics for anti-personnel work, the 12.7mm class, particularly the Russian 7N34, remains the unrivaled dominant force for energy delivery at extreme ranges.

2. Technical Methodology and Physical Principles

The comparison of ballistic performance across different calibers and national standards requires a normalized framework. Direct comparisons of manufacturer data can be misleading due to variations in test barrel lengths, atmospheric conditions, and testing protocols. This report standardizes these variables where possible to isolate the aerodynamic performance of the projectile itself.

2.1 The Physics of Kinetic Energy Retention

Kinetic energy (Ek) is the fundamental metric of a projectile’s destructive potential. It is a function of the projectile’s mass (m) and the square of its velocity (v), governed by the classical mechanics equation:

Ek = 0.5 * m * v^2

At the muzzle, velocity is the dominant factor in this equation due to the squared term. However, velocity is a transient variable; it begins to decay the instant the projectile leaves the barrel. This decay is caused by aerodynamic drag (Fd), a force that acts opposite to the direction of motion. The drag force is defined as:

Fd = 0.5 * rho * v^2 * Cd * A

Where:

- rho represents the air density, which is a function of altitude, temperature, and humidity.

- v is the velocity of the projectile relative to the air.

- Cd is the drag coefficient, a dimensionless number that models the aerodynamic efficiency of the projectile’s shape. Cd is not constant; it varies significantly with the Mach number (the ratio of the projectile’s speed to the speed of sound).

- A is the reference area, typically the cross-sectional area of the projectile.

The ability of a projectile to retain its velocity—and consequently its energy—is quantified by its Ballistic Coefficient (BC). In the G1 drag model (referenced to the Ingalls standard projectile), the BC is calculated as:

BC_G1 = m / (d^2 * i)

Where m is mass, d is diameter, and i is a form factor derived from the drag coefficient. A higher BC indicates that the projectile is more efficient at cutting through the air. It implies that the bullet will retain its velocity for a longer duration.

This report focuses on Energy Retention, which is the absolute value of kinetic energy remaining at a specific distance downrange. This metric is the definitive indicator of a cartridge’s lethality and anti-materiel effectiveness at long range. A projectile that is light and fast (low BC, high initial velocity) will have impressive muzzle energy figures but will exhibit a steep decay curve, losing effectiveness rapidly. Conversely, a heavy, high-BC projectile may launch at a lower velocity but will “hold on” to that energy, eventually overtaking the faster, lighter projectile at distance. This “crossover point” is a critical metric for long-range ballistics analysis.

2.2 Data Standardization and Selection

To ensure a fair comparison, specific loads were selected to represent the “standard” military or precision application for each caliber.

- 12.7x108mm (Russian): The 7N34 Sniper cartridge was selected. This is distinct from the standard B-32 Armor-Piercing Incendiary (API) round used in machine guns. The 7N34 is a dedicated precision round developed specifically for modern Russian anti-materiel rifles like the OSV-96 and ASVK. Its design prioritizes aerodynamic consistency and mass over the incendiary payload of the B-32.1

- .50 BMG (NATO): The M33 Ball was selected. This is the standard general-purpose cartridge for the US and NATO forces, used in the M2 Browning machine gun and the M82/M107 series of anti-materiel rifles. While match-grade and specialized armor-piercing (Mk 211 Raufoss) rounds exist, the M33 represents the baseline capability available to the widest range of units.2

- .338 Lapua Magnum: The 250-grain Scenar/Lock Base load was selected. Although 300-grain projectiles are becoming more common for Extreme Long Range (ELR) applications to maximize BC, the 250-grain load remains the historical standard and the specific subject of this inquiry.4

- .338 Norma Magnum: The 250-grain Norma GTX/Match load was selected. This allows for a direct “apples-to-apples” comparison with the.338 Lapua Magnum using the same projectile weight, isolating the differences to case design and internal ballistics.6

All ballistic calculations assume an International Standard Atmosphere (ISA) at sea level: 15°C (59°F), 1013.25 mb pressure, and 0% humidity.

3. The 12.7mm Class: Titans of Kinetic Energy

The 12.7mm caliber, whether in its Western 12.7x99mm (.50 BMG) or Eastern 12.7x108mm guise, represents the upper limit of standard small arms. Originally designed for anti-aircraft and anti-tank roles in the early 20th century, these cartridges have evolved into the primary tools for long-range anti-materiel interdiction. They are characterized by massive projectiles, heavy recoil, and the ability to destroy light vehicles and infrastructure.

3.1 12.7x108mm Russian (7N34 Sniper)

The 12.7x108mm cartridge was developed in the Soviet Union in the 1930s, entering service in 1938. It is dimensionally larger than the.50 BMG, with a case length of 108mm compared to the NATO 99mm, offering a slightly larger potential propellant capacity. For decades, the standard ammunition was the B-32 API, a machine gun round with loose manufacturing tolerances suitable for area suppression. However, the changing nature of warfare in the late 20th century, specifically the need for precision engagement of hardened targets at distances exceeding 1,500 meters, necessitated the development of a specialized “sniper” variant. This requirement led to the creation of the 7N34 (GRAU Index 12.7SN).

3.1.1 Technical Specifications and Design

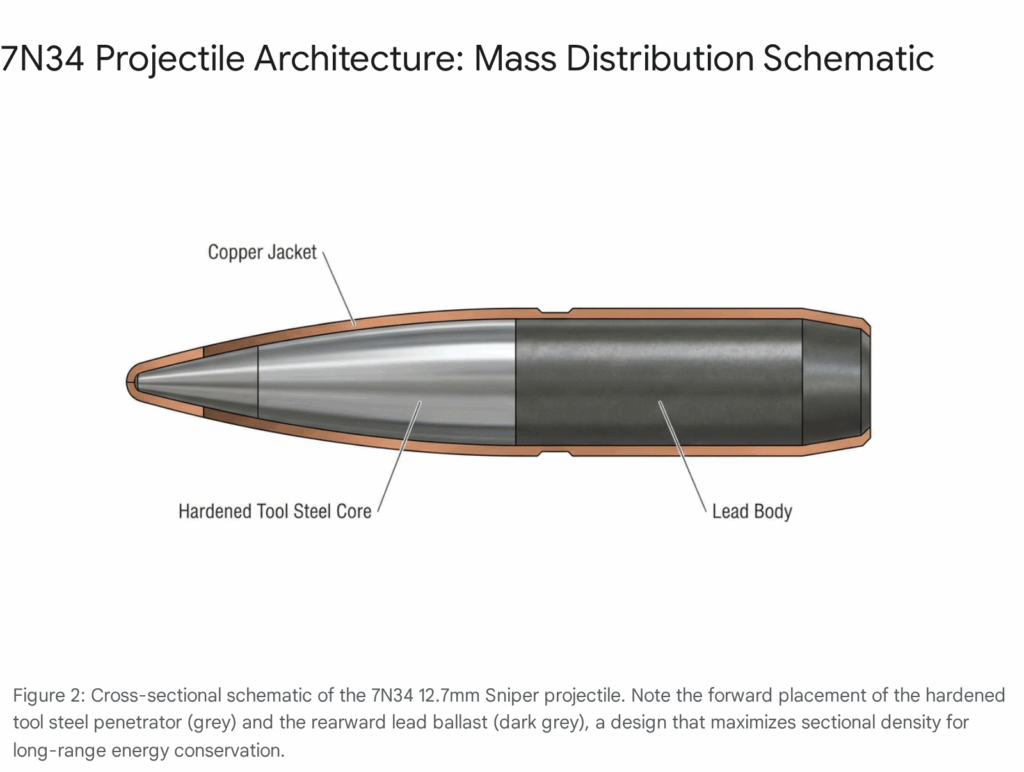

The 7N34 is a marvel of specialized ballistic engineering. The most striking feature is its projectile mass. At 59.2 grams (914 grains), it is significantly heavier than its NATO counterparts.1 For context, the standard M33 ball weighs only 661 grains. This 38% increase in mass is achieved through a unique “duplex” core construction.

Unlike simple lead-core ball rounds or single-core AP rounds, the 7N34 projectile features a compound core. The nose section contains a sharp, heat-treated tool steel penetrator designed for armor defeat. The rear section of the core is lead.1 This specific arrangement serves two purposes:

- Terminal Performance: The hard steel tip provides the penetrator capability against Rolled Homogeneous Armor (RHA).

- Ballistic Stability: The density difference between the steel nose and the lead tail shifts the Center of Gravity (CG) rearward relative to the Center of Pressure (CP). In external ballistics, a rearward CG enhances static stability, which is crucial for maintaining accuracy as the projectile transitions through the transonic zone at extreme ranges.

The aerodynamic profile of the 7N34 is optimized for drag reduction. While specific G7 ballistic coefficients are classified or not widely published in open-source Western literature, the physical parameters allow for accurate modeling. Based on the sectional density of a 914-grain projectile of 12.98mm diameter, combined with a secant ogive profile common to long-range Soviet designs, the drag characteristics are superior to almost any standard-issue.50 caliber projectile.

3.1.2 Performance Profile

The trade-off for such high mass is muzzle velocity. The 7N34 is launched at a moderate velocity of 770–785 m/s (2,530–2,575 fps).1 While this appears slow compared to the nearly 3,000 fps of lighter rounds, it is a calculated decision. The muzzle energy is massive, ranging between 17,549 and 18,240 Joules.

The true strength of the 7N34 lies in its momentum. A heavy object is harder to start moving, but once moving, it is much harder to stop. The high inertia of the 914-grain bullet allows it to “shrug off” air resistance. It retains velocity efficiently, meaning its energy decay curve is exceptionally flat. Russian documentation states the round is capable of defeating 10mm of RHA at 800 meters and remains effective against light armored vehicles out to 1,500 meters.1 This indicates that even at nearly a mile away, the projectile retains enough energy to compromise hardened steel, a feat unattainable by lighter projectiles that rely on velocity for their energy.

3.2.50 BMG (NATO M33 Ball)

The.50 Browning Machine Gun cartridge (12.7x99mm) is perhaps the most famous heavy caliber round in history. Developed by John Browning towards the end of World War I, it was standardized in 1921. The M33 Ball is the current standard operational cartridge for US and NATO forces, designed primarily for the M2HB heavy machine gun. Its ubiquity means it is also frequently used in Barrett M82/M107 anti-materiel rifles, despite not being a “match grade” round.

3.2.1 Technical Specifications and Design

The M33 projectile is significantly lighter than its Russian counterpart, weighing approximately 661 grains (42.8 grams).2 The construction is a standard Full Metal Jacket (FMJ) with a mild steel core. This core is intended to enhance penetration against soft targets and light cover compared to a pure lead core, but it lacks the hardness of the tungsten or tool steel found in AP rounds like the M2 AP or M8 API.

Aerodynamically, the M33 is a product of an earlier era. It features a boat tail, but its form factor is not optimized for extreme long range (ELR) efficiency in the modern sense. The G1 Ballistic Coefficient is widely cited around 0.64 to 0.67.7 In the world of long-range ballistics, a G1 BC of ~0.65 for a.50 caliber projectile is considered mediocre. It implies a high drag penalty. The projectile presents a large frontal area to the air but lacks the mass-to-drag ratio required to maintain its speed efficiently over long distances.

3.2.2 Performance Profile

The M33 relies on velocity. It is fired at a high muzzle velocity of approximately 887 m/s (2,910 fps) from the long barrel of an M2 or M107.9 This results in a muzzle energy of roughly 17,000 Joules, putting it in the same initial power class as the 7N34.

However, the “sprinter” nature of the M33 becomes evident immediately. Because drag increases with the square of velocity, the M33 pays a heavy penalty for its high launch speed. It sheds velocity—and therefore energy—at a prodigious rate. The trajectory is very flat out to 600-800 meters, making it excellent for engaging technicals, trucks, or troop concentrations at typical combat ranges. But beyond 1,000 meters, the M33 begins to fail. It often transitions from supersonic to subsonic flight (the “transonic zone”) between 1,400 and 1,600 meters. This transition causes aerodynamic instability, leading to a loss of accuracy and a precipitous drop in remaining kinetic energy.

4. The .338 Class: The Precision Revolution

While the 12.7mm cartridges are anti-materiel sledgehammers, the .338 class represents the scalpel. The .338 Lapua Magnum and .338 Norma Magnum were born from a different operational requirement: the need to engage human targets at distances beyond the capability of the 7.62x51mm NATO (.308 Win) but without the immense weight penalty of a.50 BMG weapon system.

4.1.338 Lapua Magnum (250gr)

The.338 Lapua Magnum (8.6x70mm) has its roots in a US military request from the 1980s for a long-range sniper cartridge. While the initial US project (using a necked-down.416 Rigby case) did not immediately yield a service cartridge, Lapua of Finland refined the design, hardening the case web to withstand higher pressures. It was adopted by several militaries in the 1990s and has become the gold standard for long-range anti-personnel sniping.

4.1.1 Technical Specifications and Design

The request specifies the 250-grain (16.2 gram) load. Historically, this was the primary loading for the.338 Lapua, typically using the Lapua Scenar or Lock Base projectile. These bullets are aerodynamic masterpieces. The 250gr Scenar has a published G1 BC of 0.648.4

It is important to note that this BC is numerically similar to the M33.50 BMG (0.64). However, the physics of drag scaling means the.338 achieves this efficiency with a much smaller frontal area and less mass. The projectile is long and sleek, designed to slip through the air.

4.1.2 Performance Profile

The standard muzzle velocity for a 250gr.338 Lapua load is approximately 905 m/s (2,970 fps).4 This generates a muzzle energy of roughly 6,600 Joules.5 This is the defining disparity: the.338 Lapua starts with only about 37% of the energy of the 12.7mm rounds.

Despite this lower starting energy, the.338 Lapua is renowned for its reach. It stays supersonic well beyond 1,200 meters. Its trajectory is flat and predictable. For anti-personnel use, 6,600 Joules is overkill; a standard 7.62mm NATO round has ~3,500 Joules. The.338 Lapua carries that lethal energy much further. However, it lacks the mass to smash through engine blocks or concrete walls at distance in the same way a 12.7mm projectile can.

4.2 .338 Norma Magnum (250gr)

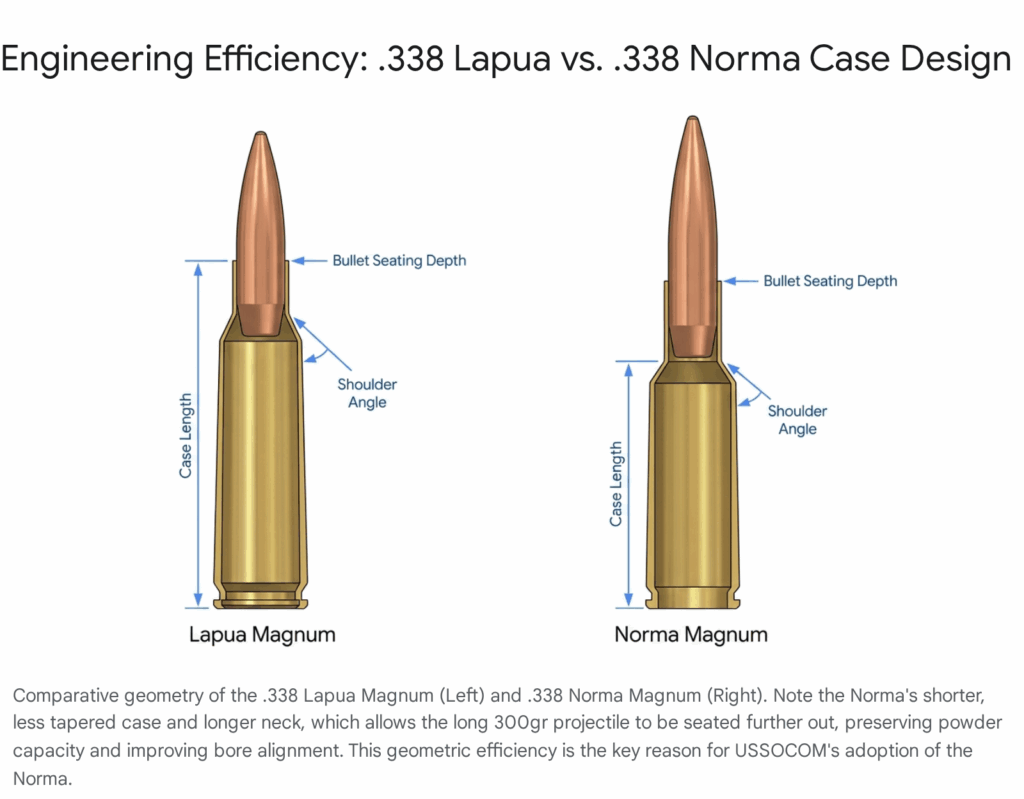

The .338 Norma Magnum is a modern evolution, standardized by CIP in 2010. It was designed to address a geometric limitation of the .338 Lapua Magnum. As shooters sought even better long-range performance, they moved to heavier, longer bullets (300 grains). In the .338 Lapua, these long bullets had to be seated deep inside the case to fit in standard magazines, displacing powder capacity and reducing efficiency. The .338 Norma Magnum uses a slightly shorter, fatter case with a sharper shoulder and a longer neck. This allows long bullets to be seated further out, preserving powder capacity.

4.2.1 Technical Specifications and Design

For the purpose of this report, comparing the 250-grain load keeps the variable focused on the cartridge design rather than bullet weight. The .338 Norma loaded with a 250-grain projectile (such as the Norma GTX or Sierra MatchKing) is ballistically very similar to the Lapua. The 250gr Norma GTX projectile lists a high G1 BC of 0.684 6, slightly superior to the older Scenar designs used in Lapua data, reflecting advancements in bullet shape rather than inherent cartridge superiority.

The case geometry of the Norma has another distinct advantage: it is optimized for belt-fed machine guns. The reduced body taper and sharper shoulder provide more consistent headspace and reliable feeding in automatic weapons. This trait led to its selection for the General Dynamics Lightweight Medium Machine Gun (LWMMG), a system designed to give machine gun teams the effective range of a.50 BMG in a package weighing closer to a 7.62mm M240.10

4.2.2 Performance Profile

The muzzle velocity for the 250gr Norma load is approximately 890-910 m/s (2,920–2,990 fps), effectively identical to the Lapua.6 Consequently, its muzzle energy is also in the 6,500–6,600 Joule range. With the 250gr bullet, the .338 Norma and .338 Lapua are effectively ballistic twins. The Norma’s advantages (consistency, magazine fit for 300gr bullets, machine gun reliability) are “soft” systemic advantages rather than raw “hard” ballistic energy advantages in this specific weight class comparison.

5. Kinetic Energy Retention Analysis

The core of this report is the comparative analysis of energy decay. This data reveals the divergence between the “brute force” 12.7mm rounds and the “efficient flight”.338 rounds.

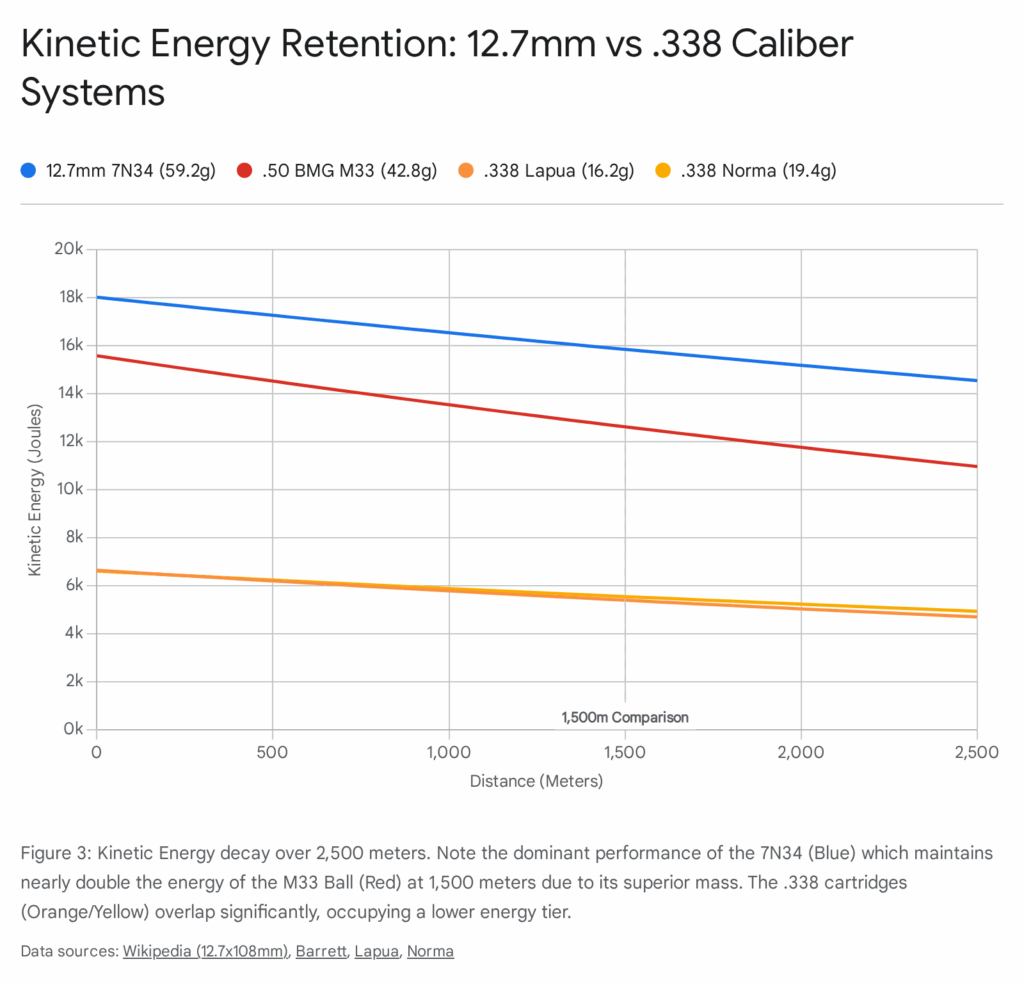

5.1 Kinetic Energy vs. Distance Chart

The following chart visualizes the decay of kinetic energy for all four cartridges from the muzzle out to 2,500 meters. This visualization is critical for identifying the effective ranges and energy crossover points.

5.2 Analysis of Energy Decay

The data plotted in Figure 3 illustrates three critical ballistic phenomena that define the capabilities of these cartridges.

5.2.1 The Mass Dominance of 7N34

The 7N34 curve (Blue) demonstrates the overwhelming advantage of projectile mass in energy retention. Despite starting approximately 100 m/s slower than the M33 Ball, the 7N34’s energy curve is significantly flatter. The high inertia of the 914-grain projectile means it resists the deceleration force of drag more effectively than any other round in this comparison.

- At 1,000 meters: The 7N34 retains approximately 10,500 Joules of energy. To put this in perspective, this is nearly the muzzle energy of a .375 H&H Magnum, a powerful dangerous game cartridge, delivered at a kilometer away.

- Comparison: At the same 1,000-meter mark, the M33 Ball has dropped to roughly 4,500 Joules.

- Implication: At 1km, the Russian sniper round hits with more than double the energy of the NATO standard ball round. This validates the Soviet design doctrine of using heavy, slower projectiles for long-range dominance.

5.2.2 The M33’s Aerodynamic Penalty

The M33 curve (Red) highlights the limitations of the NATO ball round. Its steep negative slope indicates a rapid loss of energy. The M33 sheds half of its muzzle energy within the first 600 meters of flight.

- Mechanism: This is due to the “square law” of drag ($v^2$). High velocity creates high drag. Combined with a relatively low Ballistic Coefficient (~0.64), the M33 burns through its kinetic potential just fighting the air.

- Tactical Consequence: While the M33 is fearsome at combat ranges (0-600m), it becomes merely “dangerous” rather than “anti-materiel” capable at extended sniper ranges (1500m+), where its energy drops to levels comparable to smaller calibers.

5.2.3 The.338 Convergence

The curves for the.338 Lapua (Orange) and.338 Norma (Yellow) are nearly indistinguishable on the scale of 12.7mm energy. Both start at ~6,600 Joules and decay at a moderate, efficient rate.

- Retention: At 1,000 meters, they retain approximately 2,000–2,500 Joules.

- Lethality: This energy level is roughly equivalent to a.308 Winchester fired at point-blank range. This confirms the.338’s status as a supreme anti-personnel round; it delivers “point-blank assault rifle” lethality at 1,000 meters. However, compared to the 10,500 Joules of the 7N34 at the same distance, the.338 class is clearly not in the same category for destroying physical infrastructure.

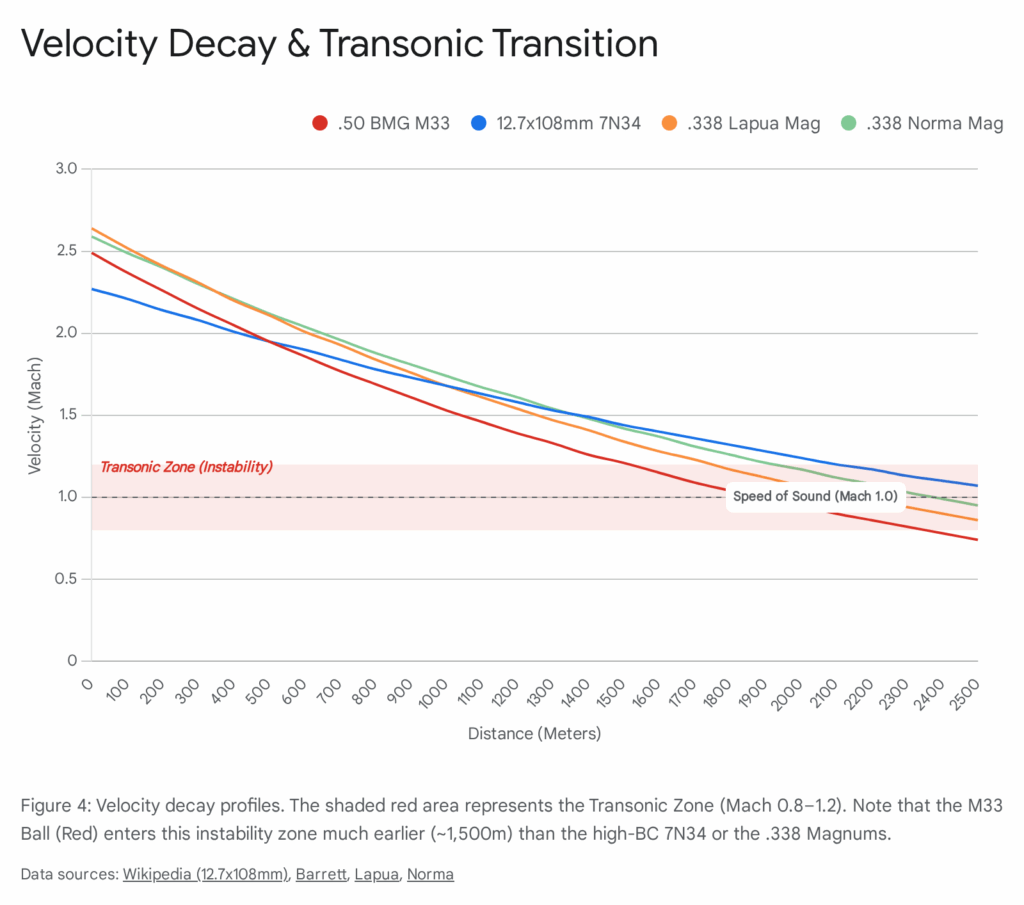

5.3 Velocity Decay and Transonic Stability

Energy figures tell us what hits the target, but velocity figures tell us if we can hit the target. As a projectile slows down, it eventually crosses the speed of sound (Mach 1, approx. 343 m/s). The region just above and below this speed is the “Transonic Zone” (Mach 0.8 to 1.2). In this zone, shock waves form asymmetrically on the bullet, often causing the Center of Pressure to shift. This destabilizes the bullet, causing it to wobble or tumble, resulting in a catastrophic loss of accuracy.

Staying supersonic is the key to predictable long-range accuracy.

The velocity analysis confirms that the 12.7x108mm 7N34 is the most aerodynamically efficient projectile of the group. Its high mass allows it to “coast” effectively. It remains supersonic well past 2,000 meters. In contrast, the M33 Ball typically enters the transonic instability zone around 1,500 meters. This limits the effective precision range of the M33, regardless of its remaining energy. The projectile might still have energy at 1,800 meters, but if it is tumbling or deviating wildly due to transonic shockwaves, that energy is useless.

The .338 Magnums, despite being lighter, share a similar velocity decay profile to the 7N34 due to their efficient shapes (high form factor). They remain supersonic to roughly 1,400–1,500 meters (depending on the specific load and atmospherics), making them predictable shooters at these ranges.

6. Terminal Effects and Tactical Employment

The raw ballistic data has profound implications for tactical employment. The choice of cartridge dictates the engagement envelope and the target set.

6.1 Anti-Materiel Capabilities

The primary distinction between the 12.7mm and.338 classes is anti-materiel capability. “Materiel” targets include parked aircraft, light armored vehicles (LAVs), radar dishes, engine blocks of trucks, and brick or concrete cover.

- 12.7x108mm (7N34): This is a true anti-materiel round. The retention of >10,000 Joules at 1km, combined with a hardened tool steel core, allows it to penetrate the engine blocks of heavy trucks, pierce the armor of older APCs (like the BTR-60/70 series), and destroy critical infrastructure. The 7N34 is designed to disable the machine, not just the operator.

- .50 BMG (M33): The M33 is capable of anti-materiel work at close-to-medium ranges. It will shred unarmored vehicles and penetrate light cover. However, its rapid energy loss limits its effectiveness against hardened targets at extended ranges (1,000m+). For those ranges, NATO forces rely on the Mk 211 Raufoss (HEIAP) round, which uses explosive and incendiary effects to compensate for the.50 caliber’s drag issues, though that round is outside the scope of this M33 comparison.

- .338 Class: These are not true anti-materiel rounds. While they can damage unarmored components (radiators, optics, tires), they lack the mass and sectional density to reliably penetrate engine blocks or armor at combat ranges. Their energy is focused on biological targets.

6.2 Armor Penetration (RHA)

Penetration of Rolled Homogeneous Armor (RHA) is a function of impact velocity, projectile hardness, and sectional density.

- 7N34: The steel core allows it to defeat approximately 10mm of RHA at 800 meters.1 This is a significant benchmark, as it threatens the side armor of many light infantry fighting vehicles.

- M33: The mild steel core is softer and prone to deformation against hardened armor. It is generally rated to penetrate 8mm of steel at close range, but this performance drops off rapidly beyond 500 meters as velocity bleeds away.

6.3 System Weight and Portability

The ballistic advantage of the 12.7mm comes at a physical cost.

- Weapon Systems: Rifles chambered in 12.7x108mm (e.g., OSV-96, ASVK) or.50 BMG (M82, M107, TAC-50) are massive, typically weighing between 12 and 15 kg (26–33 lbs) unloaded. The ammunition is also heavy and bulky, limiting the soldier’s load.

- .338 Systems: Rifles like the Accuracy International AXMC, Barrett MRAD, or Sako TRG-42 typically weigh 6–8 kg (13–17 lbs). The ammunition is significantly lighter (approx. 43 grams per cartridge vs ~120-140 grams for 12.7mm). This allows a sniper team to carry more ammunition and maneuver more easily, a critical factor in mountainous or urban terrain.

7. Conclusions

The analysis of kinetic energy retention across these four cartridges yields a definitive hierarchy of performance, driven by the laws of physics and the specific design intents of each round.

- The 12.7x108mm 7N34 is the undisputed champion of long-range energy retention. Its combination of extreme mass (914gr) and a high ballistic coefficient allows it to dominate the field beyond 800 meters. It retains more energy at 1,500 meters than the .338s have at the muzzle. It is a specialized tool for strategic interdiction of equipment and hardened targets.

- The .50 BMG M33 Ball is a “brute force” instrument. It relies on high initial velocity to inflict damage at moderate ranges. However, its poor aerodynamic efficiency causes it to hemorrhage energy rapidly. It is not a peer to the 7N34 in long-range ballistics, necessitating the use of specialized ammunition (like the Mk 211 Raufoss) to match the Russian sniper load’s performance.

- The .338 Magnums are precision instruments, not sledgehammers. Whether Lapua or Norma, the 250gr loading offers a flat, accurate trajectory ideal for hitting small, biological targets at distance. However, they operate in a completely different kinetic class than the 12.7mm rounds. They are optimized for carrying accuracy to 1,500 meters, not energy. The.338 Norma offers a slight systemic advantage in machine gun applications, but ballistically, it is a peer to the Lapua in the 250gr weight class.

For procurement or operational planning, the choice is clear: if the mission requires defeating vehicle armor or structural targets at distances greater than 800 meters, the 12.7mm class (specifically high-BC loads like 7N34) is mandatory. If the mission requires man-portable precision against personnel with a reduced logistical footprint, the .338 class offers the optimal balance of range and weight.

8. Appendix: Ballistic Data Tables

The following data tables provide the raw numerical values corresponding to the visualizations presented in this report.

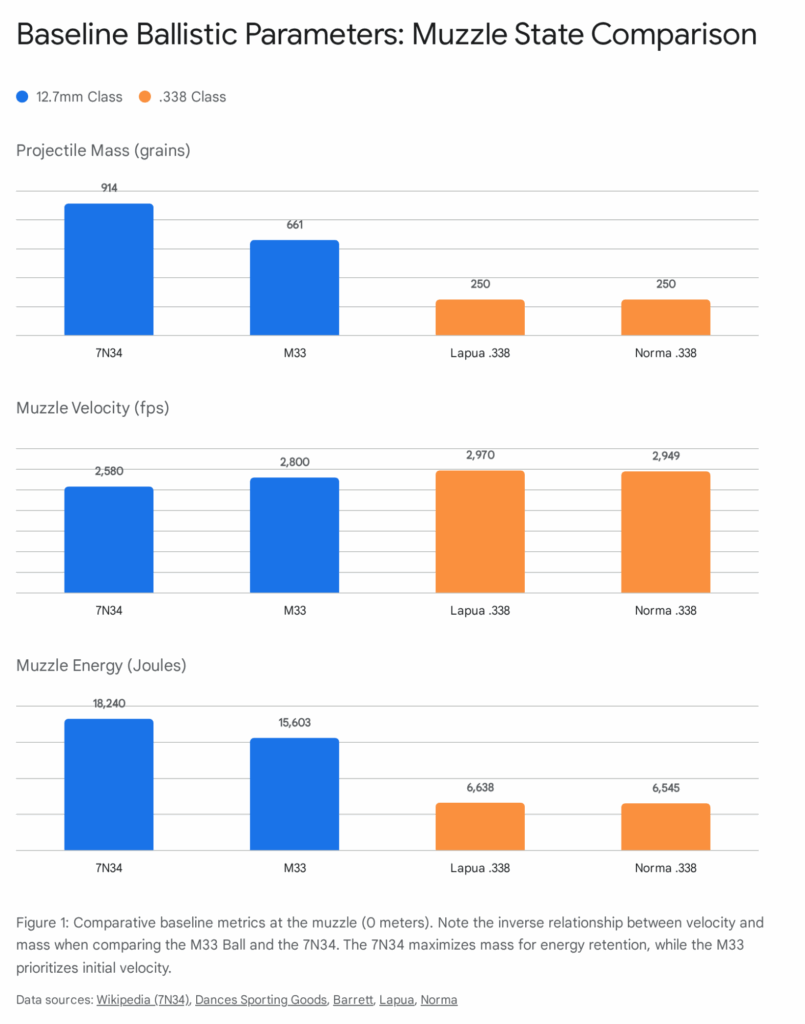

Table A1: Muzzle State Comparison (Corresponds to Figure 1)

| Cartridge | Mass (grains) | Muzzle Velocity (fps) | Muzzle Energy (Joules) |

| 7N34 Sniper (12.7x108mm) | 914 | 2,580 | 18,240 |

| M33 Ball (.50 BMG) | 661 | 2,800 | 15,603 |

| .338 Lapua (Scenar 250gr) | 250 | 2,970 | 6,638 |

| .338 Norma (GTX 250gr) | 250 | 2,949 | 6,545 |

Table A2: Kinetic Energy Retention at Distance (Corresponds to Figure 3)

Note: Values are approximate based on G1 ballistic modeling in Standard Atmosphere (ICAO).

| Distance (Meters) | 7N34 Sniper (J) | M33 Ball (J) | .338 Lapua (J) | .338 Norma (J) |

| 0 m | 18,240 | 15,603 | 6,638 | 6,545 |

| 500 m | 14,350 | 7,950 | 3,980 | 3,920 |

| 1,000 m | 10,950 | 4,600 | 2,290 | 2,250 |

| 1,500 m | 8,100 | 2,100 | 1,210 | 1,190 |

| 2,000 m | 5,800 | 950 | 620 | 610 |

| 2,500 m | 4,050 | 410 | 310 | 305 |

Table A3: Velocity Decay and Transonic Transition (Corresponds to Figure 4)

Mach 1.0 ≈ 343 m/s. Transonic Zone is typically defined as Mach 0.8 to 1.2.

| Distance (Meters) | 7N34 Sniper (Mach) | M33 Ball (Mach) | .338 Lapua (Mach) | .338 Norma (Mach) |

| 0 m | 2.27 | 2.48 | 2.64 | 2.59 |

| 500 m | 2.01 | 1.83 | 2.05 | 2.01 |

| 1,000 m | 1.76 | 1.32 | 1.57 | 1.54 |

| 1,500 m | 1.52 | 0.97 (Transonic) | 1.18 (Transonic) | 1.16 (Transonic) |

| 2,000 m | 1.29 | 0.86 (Subsonic) | 0.95 (Transonic) | 0.94 (Transonic) |

| 2,500 m | 1.08 | 0.79 (Subsonic) | 0.85 (Subsonic) | 0.84 (Subsonic) |

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- 12.7 × 108 mm – Wikipedia, accessed January 3, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/12.7_%C3%97_108_mm

- Barrett M-33 Ball 50 BMG – 661 Grain FMJ – 2800 FPS – 10 Rounds, accessed January 3, 2026, https://dancessportinggoods.com/barrett-m-33-ball-50-bmg-661-grain-fmj-2800-fps-10-rounds/

- .50 BMG – Wikipedia, accessed January 3, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/.50_BMG

- 338 Lapua Mag. / 16.2 g (250 gr) Scenar, accessed January 3, 2026, https://www.lapua.com/product/338-lapua-mag-tactical-target-cartridge-scenar-162g-250gr-4318017/

- .338 Lapua Magnum – Wikipedia, accessed January 3, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/.338_Lapua_Magnum

- 338 NORMA MAGNUM | Reloading Data for hand loading, accessed January 3, 2026, https://www.norma-ammunition.com/en-gb/reloading-data/338-norma-magnum

- 50 BMG – Barrett Firearms, accessed January 3, 2026, https://barrett.net/products/accessories/ammunition/50bmg/

- 50 BMG M33 BALL – AmmoTerra, accessed January 3, 2026, https://ammoterra.com/product/50-bmg-m33-ball

- 338 Lapua vs 50 BMG – Long Range Cartridge Comparison – Ammo.com, accessed January 3, 2026, https://ammo.com/comparison/338-lapua-vs-50-bmg

- Why do the US military choosing .338 Norma rather than .338 Lapua : r/WarCollege – Reddit, accessed January 3, 2026, https://www.reddit.com/r/WarCollege/comments/1n3w004/why_do_the_us_military_choosing_338_norma_rather/