Executive Summary

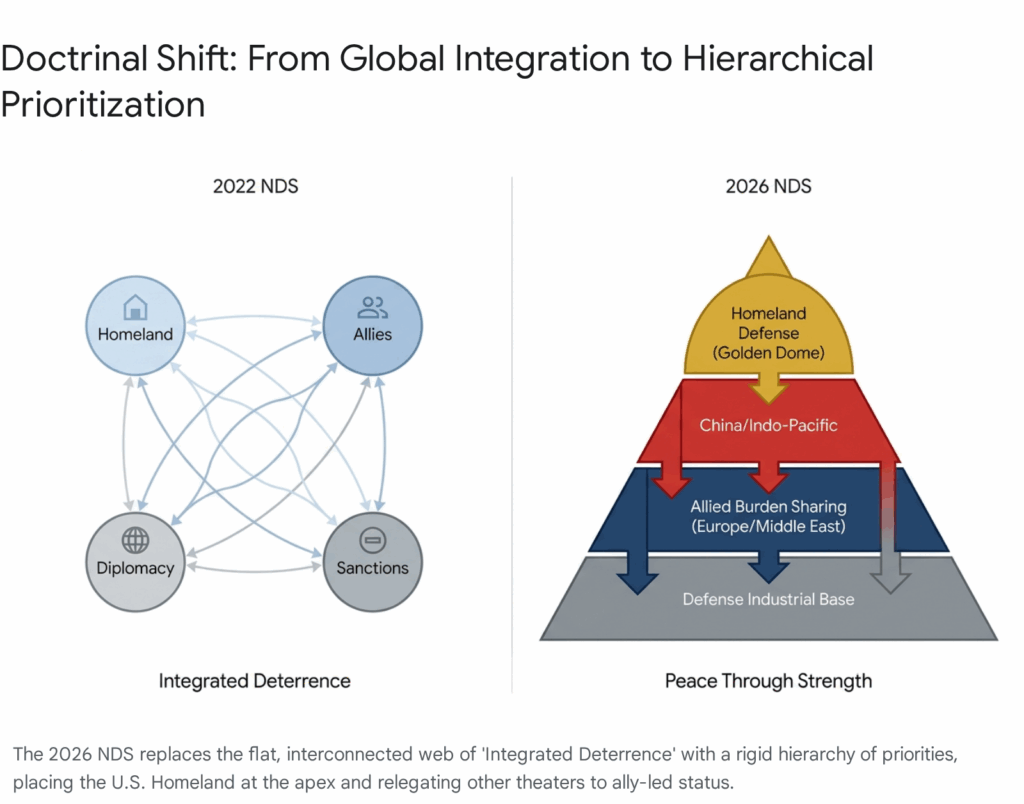

The 2026 National Defense Strategy (NDS), released by the Department of War (DoW) on January 23, 2026, marks a definitive pivot in the United States’ military posture, discarding the 2022 framework of “Integrated Deterrence” in favor of a new, assertive doctrine titled “Peace Through Strength.” This report, produced by a multidisciplinary team of national security, intelligence, warfare, and space specialists, provides an exhaustive analysis of the strategy, its origins, and its profound implications for the global order.

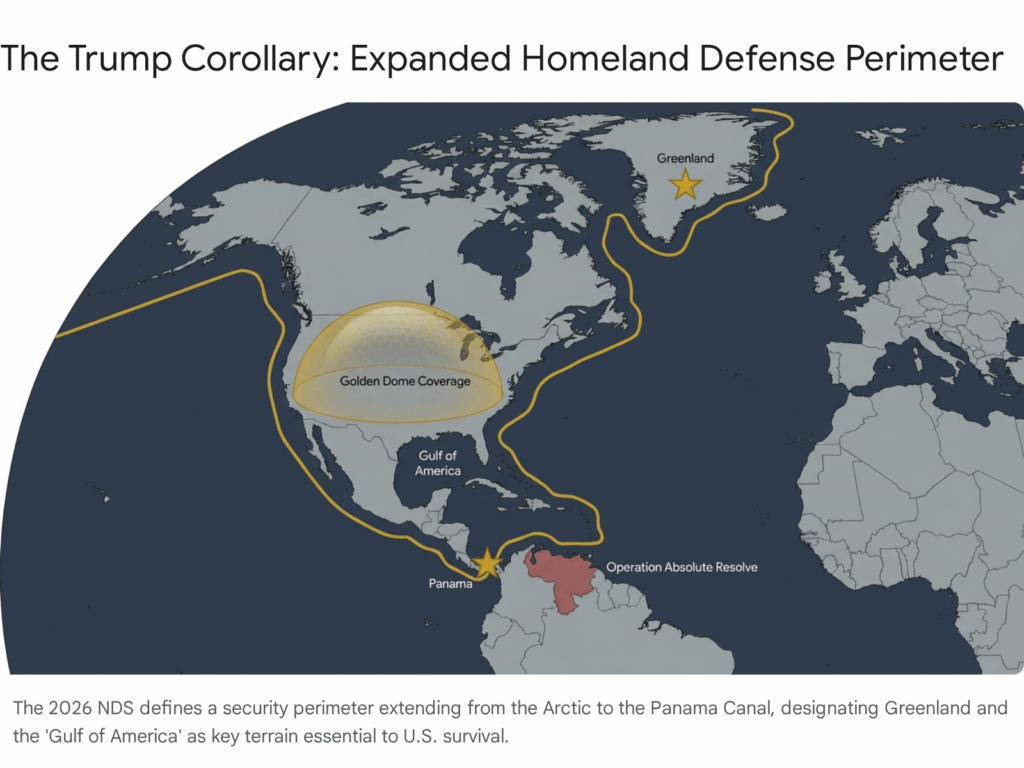

The 2026 NDS is predicated on a stark assessment of the “Simultaneity Problem”—the recognition that the United States can no longer effectively manage concurrent major theater wars against peer adversaries while maintaining global stability. To address this, the Department of War has instituted a rigorous hierarchy of priorities that places the physical defense of the American Homeland above all other commitments. This “Homeland Defense Primacy” is not merely a defensive crouch but an aggressive expansion of the security perimeter to include the entire Western Hemisphere, underpinned by the “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine.

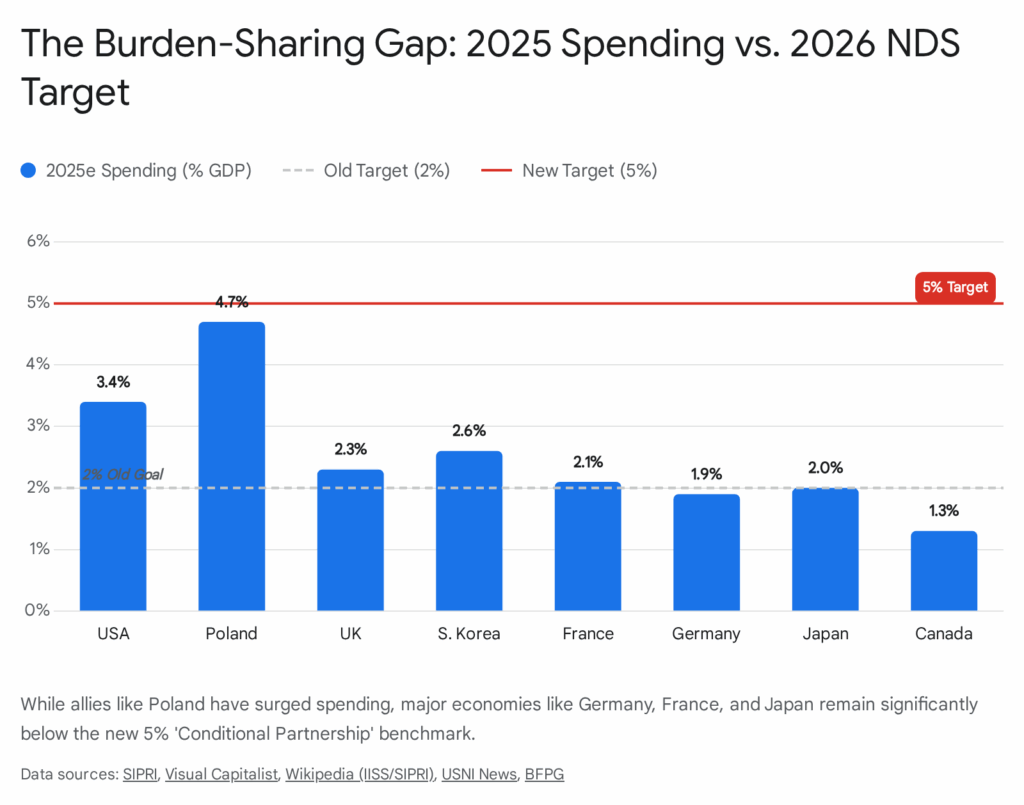

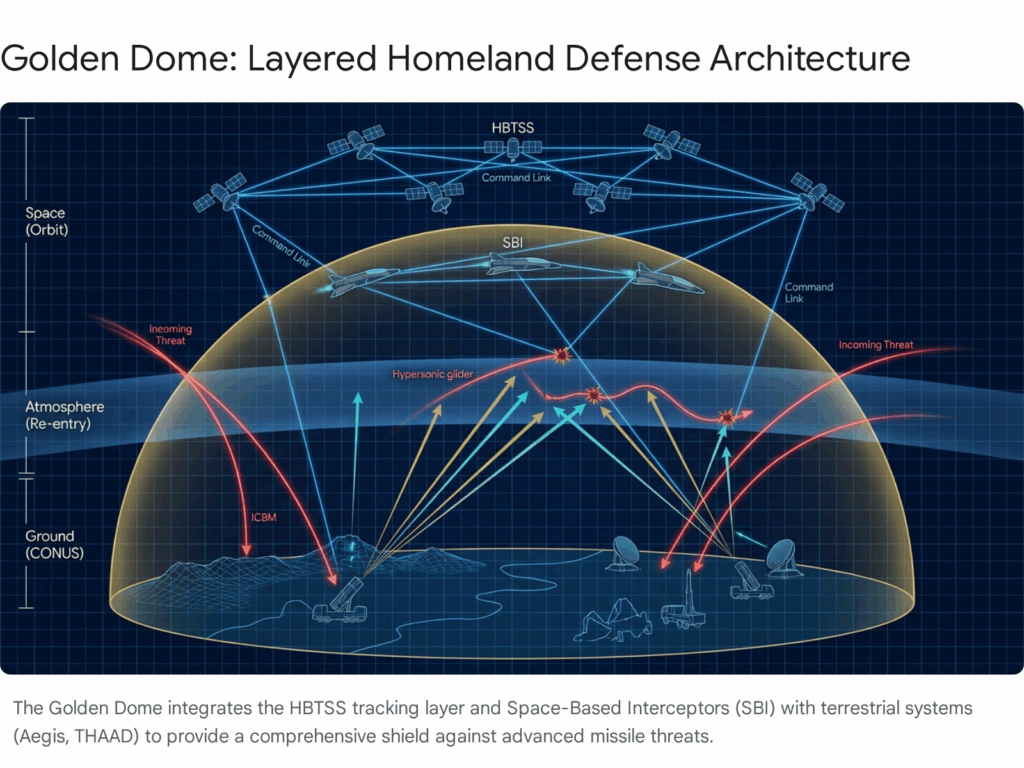

Key operational shifts include the introduction of the “Golden Dome” missile defense initiative, a massive multi-layer architecture integrating space-based interceptors to neutralize coercive threats from China and Russia. Internationally, the strategy replaces the post-Cold War norm of unconditional security guarantees with “Conditional Partnership.” This new social contract mandates a defense spending benchmark of 5% of GDP for allies—a standard formalized at the 2025 NATO Hague Summit—and explicitly ties U.S. support to allied burden-sharing. Regarding the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the strategy adopts a posture of “Deterrence by Denial” along the First Island Chain, prioritizing the prevention of regional hegemony over regime change, while notably omitting direct references to Taiwan to maintain strategic flexibility.

Official Document Access: The full text of the 2026 National Defense Strategy is available at the Department of Defense (now Department of War) official repository: (https://media.defense.gov/2026/Jan/23/2003864773/-1/-1/0/2026-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY.PDF) 1

Top 20 Key Elements of the 2026 NDS

The following table summarizes the twenty most critical components of the strategy, detailing their strategic rationale and the immediate operational ripple effects observed across the global security architecture.

| Rank | Key Element | Strategic Rationale | Operational/Strategic Implication |

| 1 | Homeland Defense Primacy | The U.S. cannot project power if the home front is vulnerable.3 | Shift of high-end assets (naval, air) to border and hemispheric defense roles; reduced forward presence. |

| 2 | “Golden Dome” Initiative | Neutralize missile coercion from peer adversaries (China/Russia).3 | Massive investment in Space-Based Interceptors (SBI) and HBTSS layers; breach of previous space weaponization norms. |

| 3 | Trump Corollary to Monroe Doctrine | Preclude external influence (China/Russia) in the Western Hemisphere.3 | Assertive control over Panama Canal, Greenland, and “Gulf of America”; potential for unilateral intervention. |

| 4 | 5% Allied GDP Target | Mitigate U.S. overstretch; force allies to lead regional defense.6 | Immense fiscal strain on EU/NATO allies; potential fracturing of the alliance due to inability to meet targets. |

| 5 | Department of War (DoW) | Cultural shift to “warfighting ethos” over bureaucratic management.3 | Symbolic and administrative restructuring emphasizing lethality and combat readiness over social programs. |

| 6 | Deterrence by Denial (China) | Prevent PLA success without guaranteeing regime change or invasion.3 | Focus on “First Island Chain” (FIC) hardening rather than deep mainland strikes; defensive posture. |

| 7 | Conditional Partnership | End “free-riding”; U.S. support is contingent on burden sharing.10 | Erosion of Article 5 automaticity; transactional alliance management based on fiscal contribution. |

| 8 | The Simultaneity Problem | Acknowledges inability to fight two major wars simultaneously.12 | Abandonment of “Two-War Construct”; rigid prioritization of China over Russia/Iran. |

| 9 | Taiwan Omission | “Strategic Silence” to avoid entrapment or immediate escalation.3 | Increases ambiguity; potentially destabilizing if interpreted as abandonment or tacit deal-making. |

| 10 | Re-Shoring the DIB | National autarky in defense production to ensure wartime resilience.1 | Protectionist trade policies; “Buy American” mandates; decoupling from Chinese supply chains. |

| 11 | “Peace Through Strength” | Deterrence relies on overwhelming capability, not treaties.2 | Increases in nuclear modernization, offensive space capabilities, and kinetic readiness. |

| 12 | SLCM-N Revival | Fill the “deterrence gap” in theater nuclear capabilities.14 | Deployment of nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missiles on naval vessels; escalation control tool. |

| 13 | Space Sanctuary End | Space is a warfighting domain requiring superiority.16 | Deployment of offensive counter-space capabilities and cislunar monitoring; “Space Superiority” doctrine. |

| 14 | Counter-Narco-Terrorism | Classifying cartels as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTO).4 | Military rules of engagement applied to cartels; unilateral strikes in hemisphere; integrated border ops. |

| 15 | Russia De-Prioritization | Russia viewed as “acute” but manageable by Europe.9 | Reduction of U.S. land forces in Europe; burden shifts to NATO’s eastern flank and EU militaries. |

| 16 | Operation MIDNIGHT HAMMER | Proof-of-concept for long-range, unilateral strikes.1 | Template for future punitive expeditions launched directly from CONUS without forward basing reliance. |

| 17 | Nuclear Modernization | Counter China’s growing arsenal (1,000+ warheads).1 | Acceleration of Sentinel ICBM and Columbia-class SSBN programs; focus on capacity and variety. |

| 18 | Strategic Assets Protection | Greenland and Panama identified as “Key Terrain”.1 | Potential increased U.S. military presence, basing, or assertive access demands in these locations. |

| 19 | Irregular Warfare Omission | Shift away from COIN/Nation-building.3 | Potential atrophy of Special Operations Forces (SOF) “gray zone” capabilities; focus on high-end conflict. |

| 20 | “Golden Dome” Czar | Centralized authority for homeland missile defense.21 | Streamlined acquisition bypasses traditional bureaucratic hurdles to accelerate deployment. |

1. Introduction: The Strategic Reset

The release of the 2026 National Defense Strategy signifies a watershed moment in American military history, representing a deliberate and stark departure from the post-Cold War consensus. While previous strategies—including the 2018 NDS and the 2022 NDS—sought to manage the rise of peer competitors through a complex web of alliances and “integrated deterrence,” the 2026 NDS diagnoses the current security environment as one of existential peril that requires a return to first principles: the uncompromised defense of the American homeland and the pursuit of peace through overwhelming military strength.

This strategic reset is driven by the conviction that the U.S. military has been weakened by decades of “rudderless” interventions, nation-building exercises, and a diffusion of focus that left the Joint Force ill-prepared for high-intensity conflict.1 The renaming of the Department of Defense to the “Department of War” is not merely cosmetic; it is a profound signal of intent, designed to strip away bureaucratic inertia and refocus the institution’s culture entirely on the “warrior ethos” and lethality.4

The document is framed by the recognition of a “Decisive Decade,” a period where the balance of power will be irrevocably settled. However, unlike the 2022 NDS which emphasized “campaigning” and “building enduring advantages” through soft power and diplomacy 18, the 2026 NDS adopts a “Jacksonian” realist perspective. It posits that the international order is fragmenting and that the United States must secure its own survival and prosperity first, engaging with the world only where “concrete interests” are at stake.1 This report analyzes the constituent elements of this new strategy, exploring how the shift from a global policeman to a “Fortress America” with global reach changes the calculus of deterrence for friends and foes alike.

2. The Strategic Environment: The Simultaneity Problem

A central analytical driver of the 2026 NDS is the formal acknowledgment of the “Simultaneity Problem”.12 For decades, U.S. defense planning was guided by the “Two-Major Theater War” (2-MTW) construct, which assumed the U.S. could fight and win two simultaneous conflicts (e.g., in the Middle East and Northeast Asia). The 2026 NDS discards this assumption as obsolete and dangerous.

2.1 The End of the Two-War Construct

The DoW assessment concludes that the proliferation of high-end military capabilities to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Russian Federation creates a risk where a conflict in one theater could encourage opportunistic aggression in another. The combined naval, nuclear, and cyber capabilities of these adversaries mean that the U.S. cannot “act everywhere on our own” without risking catastrophic failure.23

This recognition forces a ruthless prioritization. The strategy explicitly ranks threats, placing the PRC as the “pacing challenge” requiring the bulk of U.S. attention, while downgrading Russia to an “acute” but regional threat that must be managed primarily by European allies.9 This marks the end of the “blank check” era of American security guarantees.

2.2 The Threat from the People’s Republic of China (PRC)

The NDS is informed by the stark findings of the 2025 China Military Power Report (CMPR), which highlights a rapid acceleration in the PRC’s nuclear and conventional capabilities.

- Nuclear Breakout: The CMPR confirms that China is on track to field over 1,000 operational nuclear warheads by 2030, supported by the construction of three massive solid-propellant ICBM silo fields and the expansion of its liquid-fuel DF-5 force.19

- Long-Range Strike: The report identifies the fielding of the DF-27 ICBM, a hypersonic-glide vehicle equipped missile with a range of 5,000–8,000 km. This system serves as a long-range anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM) capable of threatening U.S. carrier strike groups and land targets as far away as Hawaii and potentially the continental U.S., fundamentally altering the risk calculus for U.S. intervention in the Pacific.25

- Naval Dominance: The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is confirmed to be the largest navy in the world, with a battle force of over 370 ships, expected to grow to 435 by 2030.27

2.3 The Evolution from “Integrated Deterrence”

The 2022 NDS relied on “Integrated Deterrence,” which sought to combine military power with economic sanctions, diplomatic pressure, and allied consensus to deter aggression.22 The 2026 NDS critiques this approach as insufficient for hard-power deterrence. It argues that reliance on “signaling” and non-military tools has failed to arrest the military buildups of adversaries. Instead, “Peace Through Strength” relies on the possession of undeniable, asymmetric military advantages—specifically in nuclear, space, and missile defense domains—to impose immediate and unacceptable costs on aggression.9

3. Core Pillar I: Homeland Defense (The “Trump Corollary”)

The defining feature of the 2026 NDS is the elevation of Homeland Defense from a supporting function to the absolute strategic imperative. Unlike previous strategies that viewed forward deployment as the primary means of defending the homeland (“fighting them over there so we don’t fight them here”), the 2026 NDS assumes that in a modern conflict with peer adversaries, the homeland will be a primary target of kinetic and non-kinetic attacks. Consequently, the strategy redefines the “Homeland” to encompass a strategic sphere of influence extending from the Arctic to the Panama Canal.

3.1 The “Golden Dome” Initiative

The technological centerpiece of the Homeland Defense pillar is the “Golden Dome” (formerly “Iron Dome for America”) missile defense initiative. Established by Executive Order 14186 in January 2025, this program represents the most ambitious missile defense architecture since the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI).5

Unlike the Israeli Iron Dome, which is designed for short-range rockets, the Golden Dome is a comprehensive, multi-layer shield designed to defeat the full spectrum of missile threats, including intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), hypersonic glide vehicles (HGVs), and advanced cruise missiles. The 2026 NDS prioritizes this system to negate the “coercive leverage” of China’s and Russia’s nuclear arsenals.3

3.1.1 Architectural Components

The system is described as a “system of systems” integrating three primary layers:

- Space-Based Sensing (HBTSS): The accelerated deployment of the Hypersonic and Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor (HBTSS) constellation. These satellites provide global, persistent tracking of dim, maneuvering targets (like hypersonic gliders) that terrestrial radars cannot track effectively due to the curvature of the Earth.5

- Space-Based Interceptors (SBI): In a controversial move that breaks with decades of policy regarding the weaponization of space, the Golden Dome calls for the deployment of proliferated space-based interceptors. These kinetic kill vehicles are designed to intercept missiles in the boost phase (shortly after launch), destroying them over the adversary’s territory before they can release multiple warheads or decoys.5

- Terrestrial & Terminal Defense: The integration of existing Aegis Ashore, THAAD, and Patriot batteries into a unified command and control network, augmented by new Glide Phase Interceptors (GPI) designed to engage hypersonic threats in the upper atmosphere.5

Strategic Implication: The pursuit of SBI and a comprehensive shield signals a shift away from Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) toward a posture of “damage limitation” or “denial.” By theoretically rendering the U.S. immune to limited nuclear strikes, the strategy aims to restore U.S. freedom of action in a crisis.

3.2 The “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine

The NDS explicitly references the Monroe Doctrine, updated as the “Trump Corollary.” This doctrine asserts exclusive U.S. primacy in the Western Hemisphere and declares that the U.S. will no longer tolerate “foreign adversaries” (implicitly China and Russia) establishing military, intelligence, or economic footholds in the region.3

- Key Terrain: The strategy identifies Greenland, the Panama Canal, and the “Gulf of America” (formerly Gulf of Mexico) as critical terrain essential to U.S. survival.10 This designation implies a potential revision of basing agreements or increased naval patrolling to secure these choke points. The explicit mention of Greenland reflects a strategic interest in Arctic dominance and resource control, viewing the island as a “stationary aircraft carrier” in the North Atlantic.

- Operationalizing the Corollary: The strategy warns that if regional neighbors fail to secure their territories against narco-terrorists or foreign influence, the U.S. will take “focused, decisive action” to protect its interests. Operation ABSOLUTE RESOLVE—a unilateral operation to capture Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro—is cited as a precedent for this new assertiveness.3

3.3 Border Security as National Defense

The DoW has formally integrated border security into the core NDS mission, dissolving the traditional separation between law enforcement and military operations. The classification of drug cartels as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTO) allows the employment of military assets—including cyber warfare, surveillance drones, and potentially kinetic strikes—against trafficking networks.3 This approach treats migration and drug trafficking not as civil enforcement issues but as “gray zone” invasions that threaten national sovereignty, justifying the diversion of high-end assets (such as naval vessels and P-8 Poseidon aircraft) to border protection roles.34

4. Core Pillar II: Deterrence in the Indo-Pacific

While Homeland Defense is the top priority, the Indo-Pacific remains the primary external theater. The 2026 NDS identifies the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as the “most consequential strategic competitor,” but the approach has shifted from “competition” and “management” to a harder-edged “Deterrence by Denial.” 3

4.1 Deterrence by Denial along the First Island Chain

The strategy focuses on establishing a “strong denial defense” along the First Island Chain (FIC)—the archipelago stretching from Japan through Taiwan and the Philippines to Borneo. The objective is not necessarily to defeat China in a mainland war or to pursue regime change, but to make any PLA aggression (specifically amphibious invasion or blockade) physically impossible or prohibitively costly.3

- Operational Concept: This involves transitioning from large, centralized bases (which are vulnerable to missile attack) to a dispersed posture. The strategy calls for creating a “porcupine” defense by pre-positioning resilient, precision-strike capabilities—such as anti-ship missiles, sea mines, and unmanned systems—across allied territories.

- Strategic Goal: The document explicitly states the goal is not to “strangle or humiliate” China but to negotiate from a position of strength. This nuance (“Strength, Not Confrontation”) suggests a willingness to reach a modus vivendi with Beijing if it respects the FIC boundaries.2

4.2 The Taiwan Omission

In a stunning departure from previous strategies, the unclassified 2026 NDS does not mention Taiwan by name.3 This omission has generated significant debate among analysts.

- Analysis: This is likely a calculated application of “Strategic Silence.” By focusing on the First Island Chain (of which Taiwan is the central node) rather than Taiwan specifically, the administration creates a red line based on geography rather than political status.

- Risk: This could be interpreted by Beijing as a weakening of resolve or a signal that Taiwan is a negotiable asset. Conversely, it may be intended to avoid immediate escalation while the U.S. quietly bolsters the “denial” capabilities of the island chain. However, the heavy emphasis on “Denial Defense” implies the U.S. will fight for the geography, if not the polity.9

4.3 Strength, Not Confrontation

The NDS endorses expanded military-to-military communications with the PLA to prevent accidental escalation.2 This reflects a pragmatic recognition that as China’s nuclear arsenal grows, crisis stability becomes paramount. The strategy seeks to “de-risk” the relationship while simultaneously arming the region to the teeth. The focus is on “strategic stability,” acknowledging that total victory or regime change is not a feasible or desirable military objective against a nuclear-armed peer.

5. Core Pillar III: Alliance Transformation & Burden Sharing

The 2026 NDS fundamentally rewrites the social contract of American alliances. The era of unconditional security guarantees is over; the era of “Conditional Partnership” has begun. The strategy posits that for too long, U.S. allies have “free-ridden” on American protection, allowing their own defenses to atrophy while the U.S. bore the cost.10

5.1 The 5% GDP Standard

The most significant policy shift is the formalization of the 5% GDP defense spending target for allies, agreed upon at the 2025 NATO Hague Summit.6

- Breakdown: The target is composed of 3.5% for “core military spending” (personnel, equipment, operations) and an additional 1.5% for “security-related spending” (cyber defense, critical infrastructure resilience, border security).

- Implication: This is more than double the previous 2% Wales Pledge. For major economies like Germany, France, and Japan, meeting this target requires hundreds of billions of dollars in new spending, effectively mandating a transition to a semi-war economy.

- Enforcement: The NDS implies that U.S. support will be “limited” for allies who fail to meet this benchmark. While Article 5 remains in the treaty, the level of U.S. response may be calibrated based on the ally’s contribution. The document states the U.S. will focus resources only where “concrete interests” align.23

5.2 Regional Impacts

- Europe (NATO): The strategy downgrades Russia from an “acute threat” requiring heavy U.S. presence to a “manageable” threat that European allies must handle primarily on their own.9 The U.S. role shifts to providing nuclear deterrence and high-end enablers (space, intel), while the conventional defense of NATO’s eastern flank becomes a European responsibility. This signals likely drawdowns of U.S. Army brigades in Germany and Poland.

- Indo-Pacific Allies: Japan and South Korea are pressured to assume “primary responsibility” for their immediate defense.35 For Japan, this aligns with Prime Minister Takaichi’s aggressive push for defense doubling, though the 5% target remains a steep political climb.38 For South Korea, the NDS implies a restructuring of USFK, moving away from a “tripwire” force to a support role, urging Seoul to handle the conventional DPRK threat independently.39

- Five Eyes (Intelligence): The shift to “Conditional Partnership” poses risks to the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing alliance. If trust becomes transactional, the seamless flow of intelligence that underpins the alliance could be threatened. However, the NDS views the alliance as a tool to enforce burden-sharing, potentially restricting high-level intelligence access for partners who do not “pay their dues”.40

6. Domain-Specific Strategy: Space & Cyber

The 2026 NDS treats Space and Cyber not merely as enablers of terrestrial operations but as decisive warfighting domains where the U.S. must maintain absolute “superiority”.16

6.1 Space Warfare and the “Golden Dome”

The Space Force is central to the Golden Dome architecture and the broader strategy of “Peace Through Strength.”

- Offensive Counter-Space: The strategy moves beyond resilience to “Space Superiority,” implying the development and deployment of offensive capabilities to deny adversaries the use of space in a conflict. This includes kinetic interceptors and directed energy weapons.16

- Cislunar Operations: Recognizing the strategic importance of the volume of space between the Earth and the Moon, the strategy acknowledges the need to operate in the cislunar domain to counter China’s long-term ambitions. However, current resources are prioritized for near-Earth defense.42

- Proliferated Architectures: The NDS advocates for moving away from “juicy targets”—large, expensive satellites that are easy to destroy—to proliferated constellations like the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture (PWSA). These networks of hundreds of small satellites are harder to degrade and provide redundant capability.5

6.2 Cyber Resilience

Cyber defense is framed primarily through the lens of Homeland Defense. The strategy prioritizes the protection of critical infrastructure (power, water, finance) from state-sponsored attacks (like China’s “Volt Typhoon” campaign). It advocates for a “Defend Forward” posture in cyberspace, authorizing Cyber Command to disrupt threats at their source before they can impact U.S. networks.10

7. Core Pillar IV: The Defense Industrial Base (DIB)

The NDS identifies the atrophy of the Defense Industrial Base (DIB) as a critical national security vulnerability. The strategy calls for “supercharging” the DIB, treating industrial capacity as a deterrent in itself. If the U.S. cannot produce munitions at scale, it cannot sustain a conflict.1

7.1 Re-Shoring and “Arsenal of Freedom”

The document promotes a strongly protectionist industrial policy. It seeks to eliminate dependence on foreign supply chains—particularly Chinese sources for rare earth minerals and microelectronics—for critical weapons systems.

- “Buy American” Mandates: The NDS signals stricter requirements for domestic content in defense acquisition, prioritizing U.S. manufacturers even if costs are higher.

- Multi-Year Procurement: To encourage industry investment, the DoW supports the use of multi-year procurement contracts for key munitions (missiles, artillery shells), giving the DIB the long-term certainty needed to expand production lines.43

7.2 Integrating Commercial Technology

Recognizing that innovation now moves faster in the commercial sector than in government laboratories, the NDS emphasizes the rapid integration of commercial AI, autonomous systems, and space launch capabilities. The success of “Operation Midnight Hammer” is cited as proof of the need for “agility” and “operational flexibility” derived from advanced technology. This operation serves as a case study for the DoW’s desire to launch decisive operations directly from the Homeland using advanced platforms.1

8. Domain-Specific Strategy: Nuclear Posture

The NDS is accompanied by a robust nuclear modernization agenda, driven by the assessment that the U.S. faces two nuclear peers (Russia and China) for the first time in its history. This “two-peer” reality necessitates a quantitative and qualitative expansion of the U.S. nuclear arsenal.1

8.1 Modernization of the Triad

The strategy commits to fully funding the modernization of the entire nuclear triad. This includes the Sentinel ICBM program (replacing the Minuteman III), the Columbia-class SSBN (replacing the Ohio-class), and the B-21 Raider bomber. The document explicitly rejects any delays or cuts to these programs, viewing them as the bedrock of “Peace Through Strength” and essential for deterring existential attacks.1

8.2 SLCM-N Revival

A key policy reversal in the 2026 NDS is the revival of the Nuclear-Armed Sea-Launched Cruise Missile (SLCM-N). Previously cancelled by the Biden administration, the 2026 NDS (and the FY26 NDAA) mandates its development and deployment.

- Rationale: The SLCM-N is viewed as a necessary tool to fill a perceived “deterrence gap” in theater nuclear capabilities. It provides the President with a low-yield, non-strategic nuclear option to counter Russia’s tactical nuclear advantage in Europe and China’s growing regional forces, without resorting to the use of strategic ICBMs.14

9. Critical Analysis: What is Overlooked?

Despite its comprehensive scope and clear prioritization, the 2026 NDS contains significant gaps and omissions that pose strategic risks.

9.1 The “Gray Zone” and Irregular Warfare

The strategy is heavily biased toward high-end conventional and nuclear conflict—”Peace Through Strength.” It largely overlooks Irregular Warfare (IW), unconventional warfare, and information warfare.3

- Risk: Adversaries like China and Russia thrive in the “gray zone”—the spectrum of competition below the threshold of armed conflict. By de-emphasizing IW and focusing solely on kinetic lethality, the U.S. may win the war of deterrence but lose the war of influence, narrative, and subversion. The strategy lacks a clear counter to China’s “United Front” political warfare or Russia’s disinformation campaigns.

9.2 Values-Based Diplomacy

The words “democracy” and “human rights” are conspicuously absent from the document.23 The strategy is purely transactional and realist.

- Risk: This exclusion alienates partners who align with the U.S. based on shared democratic values rather than just security interests. It may make building broad coalitions harder if the U.S. is viewed solely as a self-interested hegemon rather than a leader of the “Free World.” It undermines the “soft power” appeal that has historically been a force multiplier for the U.S.

9.3 Climate Change

In stark contrast to the 2022 NDS, which labeled climate change an “existential threat,” the 2026 NDS relegates it to a secondary “transboundary challenge” or ignores it entirely in favor of “hard” security threats.18

- Risk: This overlooks the operational impact of extreme weather on military readiness (e.g., storms damaging naval bases) and the geopolitical instability caused by resource scarcity and migration, which are drivers of conflict in the very regions the U.S. seeks to stabilize.

10. Pros and Cons of the Strategy

| Pros | Cons |

| Clear Prioritization: Solves the “Simultaneity Problem” by ruthlessly prioritizing the Homeland and Indo-Pacific, aligning ends with means and avoiding strategic overstretch. | Alliance Friction: The “Conditional Partnership” and the steep 5% GDP target may fracture NATO and alienate key allies who cannot meet the demands, leading to a weaker collective defense. |

| Deterrence Clarity: “Peace Through Strength” and the “Golden Dome” send unmistakable signals of resolve and capability to adversaries, potentially reducing the likelihood of miscalculation. | Escalation Risk: Offensive space capabilities and the forward deployment of nuclear assets (SLCM-N) may induce an arms race or crisis instability, as adversaries may feel compelled to strike first in a crisis. |

| Industrial Realism: Acknowledges the fragility of the DIB and takes concrete, albeit protectionist, steps (re-shoring) to fix the logistics of a long war, ensuring the U.S. can sustain high-intensity conflict. | Values Vacuum: Abandoning “democracy” as a strategic interest cedes the moral high ground and complicates soft power projection, potentially reducing U.S. influence in the Global South. |

| Homeland Security: Closes the vulnerability gap by treating the border and hemisphere as the primary defensive perimeter, addressing direct threats to the American populace. | Gray Zone Vulnerability: By focusing on high-end kinetic war, the strategy leaves the U.S. exposed to political warfare, subversion, and economic coercion, areas where adversaries are highly active. |

11. Conclusion

The 2026 National Defense Strategy is a bold, disruptive document that fundamentally reorients the American defense enterprise. It trades the broad, values-based inclusivity of the post-Cold War era for a sharp, geographically defined realism. By prioritizing the “Golden Dome” and the Western Hemisphere, it seeks to fortress America; by demanding 5% GDP spending, it seeks to force allies to assume the primary burden of their own defense.

The success of this strategy hinges on high-stakes assumptions: that allies will step up rather than fold under the pressure; that “Deterrence by Denial” can hold China at bay without the explicit political signaling of supporting Taiwan; and that the U.S. industrial base can be revitalized in time to meet the challenge. It is a strategy of high walls and heavy weapons—”Peace Through Strength” in its purest form.

Appendix: Methodology

This report was compiled by synthesizing 170 distinct research snippets derived from open-source intelligence (OSINT), official government documents, think tank analyses (CSIS, CNAS, RAND), and reputable defense journalism.

- Primary Sources: The unclassified text of the 2026 NDS, the 2025 National Security Strategy, Executive Order 14186 (“Golden Dome”), and the FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act.

- Analytical Framework: The “Team of Experts” persona applied domain-specific lenses:

- National Security Analyst: Focused on geopolitical realignment and alliance dynamics.

- Intelligence Analyst: Assessed threat perceptions of China (CMPR 2025) and Russia.

- Warfare Strategist: Evaluated operational concepts (Deterrence by Denial, Simultaneity Problem).

- Space Warfare Specialist: Analyzed technical feasibility and implications of the Golden Dome and space control.

- Data Validation: All quantitative data (e.g., 5% GDP target, missile ranges, budget figures) were cross-referenced against multiple sources to ensure accuracy. Discrepancies (e.g., exact costs of Golden Dome) were noted as “undetermined” based on available unclassified data.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- 2026 National Defense Strategy – Department of War, accessed January 26, 2026, https://media.defense.gov/2026/Jan/23/2003864773/-1/-1/0/2026-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY.PDF

- 2026 U.S. National Defense Strategy, accessed January 26, 2026, https://news.usni.org/2026/01/24/2026-u-s-national-defense-strategy

- 2026 National Defense Strategy, accessed January 26, 2026, https://smallwarsjournal.com/2026/01/24/2026-national-defense-strategy/

- US rolls out 2026 defense strategy with sharper focus on homeland …, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/americas/us-rolls-out-2026-defense-strategy-with-sharper-focus-on-homeland-deterring-china-greater-ally-burden-sharing/3809397

- Golden Dome (missile defense system) – Wikipedia, accessed January 26, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_Dome_(missile_defense_system)

- NATO’s new spending target: challenges and risks associated with a political signal | SIPRI, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.sipri.org/commentary/essay/2025/natos-new-spending-target-challenges-and-risks-associated-political-signal

- U.S. urges allies to increase defense spending to 5% of GDP, accessed January 26, 2026, https://english.kyodonews.net/articles/-/69162

- Publications | U.S. Department of War, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.war.gov/News/Publications/

- U.S. 2026 National Defense Strategy – New Geopolitics Research Network, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.newgeopolitics.org/2026/01/24/u-s-2026-national-defense-strategy/

- America’s new Defence Strategy and Europe’s moment of truth, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.epc.eu/publication/americas-new-defence-strategy-and-europes-moment-of-truth/

- The Transatlantic Bargain in Crisis: US-European Foreign Policy …, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.helsinki.org.rs/doc/The%20Transatlantic%20Bargain%20in%20Crisis_%20US-European%20Foreign%20Policy%20Anlysis%20in%202025.pdf

- Department of War Releases National Defense Strategy – Homeland at Forefront, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.military.com/feature/2026/01/23/department-of-war-releases-national-defense-strategy-homeland-forefront.html

- Trump Administration Releases 2026 National Defense Strategy, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/trump-administration-releases-2026-national-defense-strategy

- W76-2 – Every CRS Report, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/2026-01-08_IF12084_03ef999f9e94e8d14eb018c17c187dffbe009e02.html

- What’s New for Nukes in the New NDAA? – Federation of American Scientists, accessed January 26, 2026, https://fas.org/publication/whats-new-for-nukes-in-the-new-ndaa/

- Space warfare in 2026: A pivotal year for US readiness, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.defensenews.com/space/2026/01/05/space-warfare-in-2026-a-pivotal-year-for-us-readiness/

- How the Space Force is Preparing for War in Space | Inside The Pentagon – YouTube, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FVzQ8z15NEE

- 2022 National Defense Strategy, Nuclear Posture Review, and Missile Defense Review – DoD, accessed January 26, 2026, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.PDF

- The Pentagon’s (Slimmed Down) 2025 China Military Power Report …, accessed January 26, 2026, https://fas.org/publication/the-pentagons-slimmed-down-2025-china-military-power-report/

- Pentagon’s new defense strategy elevates Western Hemisphere, allies’ burden-sharing, accessed January 26, 2026, http://en.people.cn/n3/2026/0126/c90000-20418568.html

- Space Force Activates SOUTHCOM Component, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.airandspaceforces.com/space-force-activates-southcom-component/

- Fact Sheet: 2022 National Defense Strategy, accessed January 26, 2026, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Mar/28/2002964702/-1/-1/1/NDS-FACT-SHEET.PDF

- Pentagon’s new defense strategy pulls forces abroad to focus on homeland, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2026/01/24/pentagon-national-defense-strategy-russia-china-hegseth/

- The Next National Defense Strategy: Mission-Based Force Planning – USAWC Press, accessed January 26, 2026, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3342&context=parameters

- Department of War Just Released 2025 China Military Power Report–Full Text & Key Points Here! – Andrew Erickson, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.andrewerickson.com/2025/12/department-of-war-just-released-2025-china-military-power-report-full-text-key-points-here/

- Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2025 – DoD, accessed January 26, 2026, https://media.defense.gov/2025/Dec/23/2003849070/-1/-1/1/ANNUAL-REPORT-TO-CONGRESS-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA-2025.PDF

- Report to Congress on Chinese Naval Modernization – USNI News, accessed January 26, 2026, https://news.usni.org/2025/05/01/report-to-congress-on-chinese-naval-modernization-21

- Department of Defense Releases its 2022 Strategic Reviews – National Defense Strategy, Nuclear Posture Review, and Missile Defense Review – Department of War, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.war.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3201683/department-of-defense-releases-its-2022-strategic-reviews-national-defense-stra/

- National Security Strategy | The White House, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/2025-National-Security-Strategy.pdf

- Department of War Releases 2026 National Defense Strategy, Emphasizing Homeland Defense and ‘Peace Through Strength’, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.hstoday.us/dod-national-defense/department-of-war-releases-2026-national-defense-strategy-emphasizing-homeland-defense-and-peace-through-strength/

- Golden Dome Missile Defense System – Amentum, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.amentum.com/golden-dome/

- Press Briefing: Analyzing the 2022 National Defense Strategy – CSIS, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.csis.org/analysis/press-briefing-analyzing-2022-national-defense-strategy

- The Impact of the Second Trump Administration on Latin American Foreign Policy, accessed January 26, 2026, https://unu.edu/cris/journal-article/impact-second-trump-administration-latin-american-foreign-policy

- DoD’s Shifting Homeland Defense Mission Could Undermine the …, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.csis.org/analysis/dods-shifting-homeland-defense-mission-could-undermine-militarys-lethality

- U.S. defense strategy downplays China threat and says it will limit support for allies, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2026/01/25/asia-pacific/us-national-defense-strategy-2026/

- Agreement on 5% NATO defence spending by 2035 – Wikipedia, accessed January 26, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agreement_on_5%25_NATO_defence_spending_by_2035

- Pentagon releases National Defense Strategy, with homeland defense as top priority, accessed January 26, 2026, https://breakingdefense.com/2026/01/national-defense-strategy-hegseth-pentagon-western-hemisphere/

- No request from U.S. to boost defense spending to 5% of GDP: Japan PM, accessed January 26, 2026, https://japantoday.com/category/politics/no-request-from-u.s.-to-boost-defense-spending-to-5-of-gdp-japan-pm

- Shift in nature of USFK could accelerate return of OPCON to South Korea – Hankyoreh, accessed January 26, 2026, https://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_international/1241735.html

- The Five Eyes Alliance Can’t Afford to Stay Small | Lawfare, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/the-five-eyes-alliance-can-t-afford-to-stay-small

- Five Eyes Become Three Blind Mice | Washington Monthly, accessed January 26, 2026, https://washingtonmonthly.com/2025/11/20/five-eyes-three-blind-mice-trust-crisis/

- Space Force Vice Chief Says Service Should Be Thinking About Cislunar, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.airandspaceforces.com/vice-chief-space-force-cislunar/

- THE FY26 NDAA: IMPLEMENTING PRESIDENT TRUMP’S PEACE THROUGH STRENGTH AGENDA, accessed January 26, 2026, https://armedservices.house.gov/uploadedfiles/fy26_ndaa_conference_text_legislative_summary.pdf

- 2022 National Military Strategy – Joint Chiefs of Staff, accessed January 26, 2026, https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/NMS%202022%20_%20Signed.pdf

- 2022 National Defense Strategy, accessed January 26, 2026, https://comptroller.war.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2025/FY2025_Budget_Request.pdf