So far, we have covered the history of Yugoslavian and Soviet relations and then the two Albanian defectors and early Yugo AK development leading to the M64 but we glossed over an enduring mystery that deserves its own post. In this artice, we dive into the riddle of what third world nation Yugoslavia purchased 2,000 Soviet AK-47 rifles from to reverse engineer and why it had to be covert.

A. The Core Question and Its Significance

This report addresses the question of the identity of the “Third World nation” from which the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia secretly procured approximately 2,000 Soviet-designed AK-47 assault rifles in 1959. This transaction, a relatively obscure event in the annals of Cold War arms proliferation, was nonetheless of considerable importance for Yugoslavia’s military development. The acquisition of these rifles proved pivotal for Zastava Arms, Yugoslavia’s premier weapons manufacturer, in its ambitious endeavor to independently develop and produce a domestic version of the Kalashnikov rifle. This effort culminated in the Zastava M70, a weapon that would become a mainstay of the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) and a significant export item.1

The clandestine nature of this purchase and the persistent anonymity of the supplier nation underscore the intricate geopolitical landscape of the late 1950s. Yugoslavia, under Marshal Josip Broz Tito, navigated a complex path of non-alignment, maintaining independence from both the NATO and Warsaw Pact blocs. This unique position influenced its foreign policy and its methods of military procurement, often necessitating unconventional approaches to acquire advanced weaponry.

B. Methodology and Scope

The analysis herein is based on an examination of available research materials, encompassing English, Russian, Serbian, and Arabic language sources. A central piece of evidence for this specific arms deal is C.J. Chivers’ comprehensive work, The Gun: The AK-47 and the Evolution of War.1 This report will critically assess the claim made by Chivers, situating it within the broader context of Soviet arms export policies of the era and Yugoslavia’s diplomatic and military relations. The objective is to evaluate the plausibility of potential candidate nations and, if the evidence permits, to identify the most likely intermediary.

C. Unraveling the Layers of Secrecy

The clandestine nature of the 1959 rifle purchase points towards a multi-faceted diplomatic maneuver. Yugoslavia, due to its political estrangement from the Soviet Union following the 1948 Tito-Stalin split, could not openly or directly procure sensitive military technology like the AK-47 from Moscow.1 The term “secret purchase” strongly implies a deliberate effort to bypass official channels and to shield the transaction from public scrutiny, particularly from Soviet intelligence. A “Third World nation” already receiving Soviet military aid would have had legitimate access to such weapons. This intermediary role could have offered benefits to all parties: the supplier nation might have gained financially or strengthened its diplomatic ties with Yugoslavia; Yugoslavia would secure the much-needed rifles for its reverse-engineering program. The Soviet Union itself might have tacitly approved such a transfer if it served a broader, albeit unstated, strategic objective, such as subtly bolstering a non-aligned nation’s defense capabilities against Western influence without direct Soviet commitment. Alternatively, the Soviets might have been unaware of, or unable to prevent, a relatively small diversion of arms.

The specified quantity of “approximately 2,000” rifles is a critical detail. This number is substantial enough to provide a sufficient sample base for detailed reverse engineering, including disassembly, metallurgical analysis, live-fire testing, and comparison of components – a significant step up from the mere two rifles acquired earlier from Albanian defectors which proved insufficient.1 Simultaneously, a batch of 2,000 units is arguably small enough to have been diverted from a larger consignment of Soviet military aid, or siphoned from existing stockpiles within the recipient nation, without triggering immediate alarm or major geopolitical fallout. Soviet aid packages to favored client states, such as Egypt or Iraq, were often extensive.2 Diverting such a quantity, especially if oversight and record-keeping for every individual small arm were not meticulously stringent, would be more feasible and less likely to provoke a severe diplomatic crisis than, for example, the unauthorized transfer of tanks or combat aircraft.

II. Yugoslavia’s Pursuit of the Kalashnikov: A Non-Aligned Nation’s Arms Dilemma

A. The Political Context: Independence and Necessity

Yugoslavia’s foreign policy under President Tito was characterized by a resolute commitment to independence and non-alignment. This stance meant a refusal to join the Warsaw Pact, leading to periods of significant political tension with the Soviet Union, particularly in the aftermath of the 1948 Informbiro period.1 While relations with Moscow experienced thaws and freezes, Yugoslavia could not depend on the Soviet Union for direct, licensed production of critical military hardware such as the AK-47 assault rifle.1 Consequently, the nation adopted a pragmatic approach to arms procurement, seeking weaponry and military technology from both Eastern and Western sources as opportunities arose.6 The inability to secure technical specifications for the AK-47 directly from the USSR compelled Zastava Arms, the national arsenal, to embark on the challenging path of reverse engineering.1

B. Early Steps: The Albanian Defectors’ Rifles

A significant, albeit insufficient, breakthrough occurred in 1959 when two Albanian soldiers defected to Yugoslavia, bringing with them their Soviet-manufactured AK-47s.1 These weapons were promptly handed over to Zastava engineers for detailed examination. While the engineers were able to create metal castings from these two samples, they quickly realized that this limited number of rifles did not provide enough technical data to fully understand the design intricacies, material specifications, or manufacturing processes required to reproduce the weapon or its components accurately.1 This initial encounter with the Kalashnikov highlighted the pressing need for a larger quantity of rifles to complete the reverse-engineering process successfully.

C. The Imperative for More Samples: The Road to the Zastava M70

The development of what would become the Zastava M70 assault rifle took place between 1962 and 1968, with the rifle officially entering service with the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) in 1970.1 The acquisition of a more substantial batch of AK-47s in late 1959 would have been a critical enabler for this development timeline, providing Zastava’s engineers with the necessary physical examples for comprehensive study and analysis. The Zastava M70 was ultimately an unlicensed derivative, closely based on the Soviet AK-47 Type 3 variant.1 The AK-47 Type 3, which featured a milled receiver, was produced by the Soviet Union from 1955 until 1959, when it began to be phased out in favor of the modernized, stamped-receiver AKM.8 This transition in Soviet production could have made surplus Type 3 models more readily available through third-party channels.

Yugoslavia’s unique non-aligned status presented both challenges and opportunities. It constrained direct access to Soviet military technology but simultaneously allowed Belgrade to cultivate a wide network of relationships with numerous “Third World” nations, many of which were emerging from colonial rule or navigating their own paths between the Cold War blocs. Several of these nations became recipients of Soviet military assistance as Moscow sought to expand its global influence.2 Yugoslavia’s prominent role within the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), of which it was a founding member 4, provided a diplomatic framework that could facilitate discreet arms deals and technology transfers that would have been impossible through conventional East-West channels. This network of non-aligned partners became an invaluable asset for Yugoslavia’s unconventional procurement strategies.

The sequence of events in 1959 – the arrival of the Albanian defectors’ rifles early in the year, the rapid assessment by Zastava that these were insufficient, and the subsequent “secret purchase” of approximately 2,000 additional AKs “by the end of the year” 1 – suggests a swift and opportunistic response by Yugoslav intelligence and arms procurement agencies. Once the limitations of the initial two samples became clear, an active search for more examples was likely initiated, leveraging existing diplomatic or intelligence contacts, or rapidly activating networks to locate and secure a larger quantity of the desired rifles. This was not a passive waiting game but a proactive effort to seize any available opportunity.

III. The 1959 Transaction: Corroborating the “Secret Purchase”

A. C.J. Chivers’ “The Gun” as the Primary Source

The specific assertion that “by the end of the year , however, the Yugoslav government had obtained more early pattern AKs from an unidentified Third World nation that was receiving Soviet military aid” is directly attributed to C.J. Chivers’ book, The Gun, published in 2011, on pages 250-251.1 Chivers, a former Marine officer and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, produced a work generally acclaimed for its meticulous research into the history of automatic weapons, with a particular focus on the Kalashnikov.12 His book meticulously documents the origins, global proliferation, and multifaceted impact of the AK-47 and its variants. The information provided indicates that this 1959 purchase was crucial, furnishing Zastava Arms with a sufficient number of AK-47s to “study and effectively reverse engineer the weapon type”.1

B. Contextualizing the Purchase in Zastava’s M70 Development

The timeline and technical details surrounding the development of the Zastava M70 lend credence to Chivers’ account. The Zastava M64, an early prototype that directly led to the M70, incorporated design features heavily based on the Soviet AK-47 Type 3, which utilized a milled receiver.1 Soviet production of the Type 3 AK-47 spanned from 1955 to 1959.8 This aligns perfectly with the claim that Yugoslavia acquired “early pattern AKs” in 1959, as these would likely have been Type 3 models. The successful reverse-engineering effort, facilitated by this larger batch of rifles, enabled Zastava to commence unlicensed production of its AK-47 derivative in 1964.1 This production start date is consistent with a 1959 acquisition followed by several years of intensive research, development, and tooling.

The fact that the Soviet Union began to replace the AK-47 with the modernized AKM (Avtomat Kalashnikova Modernizirovanniy) in 1959 is also significant.8 The AKM featured a stamped sheet-metal receiver, making it lighter and cheaper to mass-produce than the milled-receiver AK-47 Type 3. This transition in Soviet small arms production could have rendered existing stocks of AK-47 Type 3s obsolescent in Soviet eyes, or at least less critical. Consequently, Soviet client states that had received Type 3s might have found it easier to re-transfer a portion of their inventory, perhaps in anticipation of receiving newer AKM models. Such a re-transfer, especially of older models, might have been viewed as less diplomatically sensitive by the Soviets or easier for the intermediary nation to justify. Thus, the “early pattern AKs” mentioned by Chivers were likely Type 3s, a plausible type of weapon to be involved in a clandestine deal of this nature at that specific time.

The absence of other readily available public sources explicitly naming the “Third World nation” involved in this specific 1959 transaction is noteworthy. This suggests that C.J. Chivers may have had access to unique primary sources, such as declassified intelligence reports, internal Zastava documents, or interviews with individuals directly or indirectly involved, which are not yet in the public domain or widely known to other researchers. Alternatively, the details of this transaction may remain obscure precisely because of the success of the secrecy that originally enveloped it. The conclusions drawn in this report must, therefore, rely on interpreting Chivers’ historically credible claim within the broader framework of circumstantial evidence regarding Soviet arms recipients and Yugoslav foreign relations during this period.

IV. Identifying Potential Supplier Nations: Soviet Arms in the “Third World”

A. Overview of Soviet Military Aid and AK-47 Proliferation (Late 1950s)

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union strategically employed military aid as a key instrument of its foreign policy, aiming to expand its influence, support ideologically aligned regimes, and counter Western power.10 The AK-47 assault rifle, renowned for its simplicity, reliability, and ruggedness, became a ubiquitous symbol of this policy. It was widely supplied to “developing countries,” nations espousing communist ideals, and various national liberation movements that Moscow sought to cultivate as allies or proxies.11 By the late 1950s, a significant number of “Third World” nations across the Middle East, Asia, and Africa had become recipients of Soviet military assistance, which often included consignments of AK-47s.2 The AK-47 (Type 3) was the standard Soviet rifle until the introduction of the AKM in 1959, meaning that AK-47s were already in circulation through Soviet supply lines to these recipient states prior to or during that year.8

B. Egypt: A Prime Candidate

- Soviet-Egyptian Arms Deals: Egypt, under Gamal Abdel Nasser, emerged as a major recipient of Soviet bloc weaponry following the landmark Egyptian-Czechoslovak arms deal announced in September 1955.25 This agreement, valued at over $83 million, effectively ended the Western monopoly on arms supplies to the Middle East and signaled a significant geopolitical shift.2 The 1955 deal explicitly included small arms and munitions.25 While the initial manifests detailed in the provided material do not itemize AK-47s specifically, subsequent Soviet military aid to Egypt was extensive and continuous. By 1966, the total value of Soviet military equipment extended to the United Arab Republic (UAR), of which Egypt was the dominant part, reached $1.16 billion, with approximately 90% of this aid reportedly delivered by that time.2 This substantial aid program commenced in 1955.2 Given the AK-47’s status as the standard Soviet infantry rifle during this period, it is highly probable that significant quantities were supplied to the Egyptian armed forces well before 1959. Russian sources confirm deliveries of various Soviet armaments to Egypt between 1955-1957, including tanks, artillery, and aircraft, though specific numbers for AK-47s are not provided in these particular texts.26 The AK-47 was indeed being developed into the AKM by 1959, implying its prior establishment.27

- Yugoslav-Egyptian Relations: Relations between Yugoslavia and Egypt were exceptionally close during this period. Both countries were founding and influential members of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), sharing a common vision of independence from superpower blocs.4 Diplomatic ties strengthened considerably following the 1948 Soviet-Yugoslav split and the 1952 Egyptian Revolution.4 The year 1959, the precise timeframe of the AK-47 purchase, was marked by high-level diplomatic exchanges: President Tito visited Egypt in February 1959, and President Nasser visited Yugoslavia in November 1959.29 Such frequent top-level interactions indicate a robust and trusting political relationship, conducive to arranging sensitive, clandestine transactions. Furthermore, there is a documented instance from 1954 where Egypt is believed to have supported Yugoslav efforts to arm Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) rebels by nominally purchasing Yugoslav-made weapons, which were then discreetly transferred to Algeria.4 This historical precedent suggests a pattern of cooperation in complex, covert arms movements involving both Egypt and Yugoslavia, making Egypt a very strong candidate.

C. Iraq: A Plausible Alternative

- Soviet-Iraqi Arms Deals: Iraq emerged as another significant recipient of Soviet military assistance following the 14 July Revolution in 1958, which overthrew the Hashemite monarchy and established a republic under Abd al-Karim Qasim.30 The new Iraqi regime quickly pivoted away from Western alliances and sought closer ties with the Soviet bloc and non-aligned nations. In February 1959, the Soviet Union extended a substantial loan of $137.5 million to Iraq for economic and technical development, which likely included provisions for military hardware.32 The USSR became a major arms supplier to Iraq commencing in 1958.3 While specific quantities of AK-47s delivered to Iraq between 1958 and 1959 are not detailed in the available materials, it is highly probable that these rifles formed part of the initial arms packages supplied to the new revolutionary government. Later Iraqi consideration of replacing Kalashnikovs with M16s implies prior widespread adoption of the Soviet rifle.33

- Yugoslav-Iraqi Relations: Diplomatic relations between Yugoslavia and Iraq were formally established in 1958, in the immediate aftermath of the Iraqi revolution.30 Crucially, a Trade and Cooperation Agreement between Yugoslavia and Iraq was signed and came into force on February 19, 1959.30 This development aligns perfectly with the timeframe of the secret AK-47 purchase later that year. Yugoslavia would go on to become a major arms exporter to Iraq, particularly during the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s 30, indicating the foundation of a long-standing military-technical relationship that may have had its early, discreet origins in transactions like the one in question. The new Iraqi regime, eager to assert its independence and forge new international partnerships, might have been willing to facilitate such a transfer to Yugoslavia to build goodwill, for financial considerations, or as part of its broader realignment.

D. Other “Third World” Recipients (Brief Assessment)

- Syria: Syria had been a recipient of Soviet military aid since the early 1950s.34 However, early arms supplies from other Eastern Bloc countries like East Germany sometimes consisted of WWII surplus before transitioning to more modern Soviet-pattern weapons like the AK-47, typically in later periods (e.g., post-1967 for significant AK-47s from GDR).34 While direct Soviet supply lines to Syria for AK-47s would have existed by 1959, the available information does not highlight the same degree of intimate political alignment or specific diplomatic activity with Yugoslavia in 1959 that is evident with Egypt or the nascent relationship with Iraq.

- Indonesia: Indonesia began receiving Soviet arms, with initial deliveries noted in 1958 (such as GAZ-69 military vehicles).35 The extent to which AK-47s were delivered and available in sufficient quantity for a 2,000-unit re-transfer by late 1959 is not clearly established by the provided sources.

- India: India started to receive Soviet military technology and arms, including licenses for local manufacture, primarily in the 1960s, although some foundational agreements may have been laid earlier.22 The timeline for substantial AK-47 deliveries to India that could have been re-transferred by 1959 appears less probable compared to Middle Eastern recipients.

- Cuba: The Cuban Revolution, led by Fidel Castro, triumphed in January 1959. Significant Soviet military assistance to Cuba commenced in the early 1960s, notably escalating around the time of the Bay of Pigs invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis.36 It is therefore highly unlikely that Cuba would have been in a position to act as a supplier of Soviet-made AK-47s to Yugoslavia in 1959.

- African Nations (e.g., Angola, Ethiopia, Mozambique): While the Soviet Union did provide arms to various African states and liberation movements 37, the large-scale proliferation of AK-47s to these specific sub-Saharan African nations is generally associated with independence struggles and post-colonial conflicts of the 1960s and 1970s, rather than a 1959 timeframe for re-export.

The political ideologies and strategic alignments of these potential Third World suppliers are crucial factors. A nation deeply enmeshed within the Soviet ideological sphere might have been less inclined to engage in an unauthorized or clandestine re-transfer of Soviet-supplied arms. However, many “Third World” recipients of Soviet aid, while benefiting from Moscow’s support, pursued their own distinct national interests. Egypt under Nasser, for instance, adeptly navigated the Cold War currents, leveraging relations with both East and West to its advantage.25 Such a nation, particularly one like Egypt that shared leadership with Yugoslavia in the Non-Aligned Movement, might have viewed a discreet arms deal as a means of strengthening its own non-aligned credentials, assisting a fellow NAM state, or gaining diplomatic or economic leverage, even if it involved Soviet-origin weaponry. Iraq, with its new revolutionary government, was in a phase of actively seeking new international partnerships and asserting its autonomy, which could have provided a motive for such a transaction.

Furthermore, a secret arms purchase of this nature would necessitate a degree of trust and established communication channels. Yugoslavia, as a key architect and proponent of the Non-Aligned Movement, actively cultivated diplomatic, economic, and intelligence relationships with a wide array of nations within this group.4 This favors nations with which Yugoslavia had demonstrably active and positive diplomatic interactions in or before 1959, such as Egypt, and the rapidly developing ties with post-revolution Iraq.

Table 1: Assessment of Potential “Third World” Nations for the 1959 AK-47 Transfer to Yugoslavia

| Candidate Nation | Recipient of Soviet Military Aid (incl. AK-47s) by 1959? (Evidence & Likelihood) | Nature & Strength of Yugoslav Relations by 1959 (Political, Diplomatic, Military) | Specific Chronological Markers Supporting/Contradicting 1959 Transfer | Plausibility as the “Unnamed Nation” | Key Supporting Snippets |

| Egypt | Yes. Major recipient since 1955. Highly likely to possess AK-47s in quantity. | Very Strong. Founding NAM members, frequent high-level visits (Tito Feb ’59, Nasser Nov ’59). Precedent of arms facilitation. | Supports: Close ties in 1959. Soviet arms flow well established. | High & Most Likely | 2 |

| Iraq | Yes. Recipient since 1958 revolution. Likely included AK-47s in early packages. | Developing. Diplomatic relations established 1958. Trade/Cooperation agreement effective Feb 1959. | Supports: New regime seeking partners. Trade agreement in place. | High, but second to Egypt | 3 |

| Syria | Yes. Recipient since early 1950s. | Moderate. Established relations, but less intimacy highlighted for 1959 specifically compared to Egypt/Iraq. | Possible, but less direct evidence of specific 1959 impetus. | Medium | 34 |

| Indonesia | Yes. Initial Soviet arms deliveries in 1958. | Moderate. | Less clear if AK-47s available in sufficient quantity for re-transfer by late 1959. | Low-Medium | 35 |

V. The “Unnamed Nation”: Deciphering the Secrecy

A. Motivations for Anonymity

The enduring anonymity of the supplier nation in most historical accounts points to a convergence of interests in maintaining secrecy:

- Yugoslavia’s Perspective: For Yugoslavia, discretion was paramount. The country meticulously maintained a delicate geopolitical equilibrium between the Eastern and Western blocs. Openly acknowledging a clandestine arms deal involving Soviet-origin weapons, even if acquired through a third party, could have unnecessarily strained its already complex relationship with the USSR. It might also have compromised its carefully cultivated image as a genuinely non-aligned nation, potentially inviting suspicion or pressure from either superpower.

- The Supplier Nation’s Perspective: The intermediary country would have had strong reasons to ensure the transaction remained covert. Re-transferring military aid, particularly weapons as significant as assault rifles, without the explicit consent or knowledge of the original supplier (the Soviet Union) could have invited serious repercussions. These could range from a curtailment of future Soviet aid to diplomatic censure or other punitive measures. Protecting its own ongoing diplomatic and trade relationships with both the USSR and Yugoslavia, as well as other international actors, would have been a key concern.

- Soviet Perspective (if aware or subsequently discovered): Even if Soviet intelligence became aware of the transfer, Moscow might have preferred the matter to remain quiet. If the USSR tacitly approved the deal for its own strategic reasons – for instance, to subtly aid Yugoslavia’s independent defense posture without direct involvement, thereby keeping it from leaning too heavily towards the West – publicity would be counterproductive. Conversely, if the transfer occurred without Soviet knowledge or approval, publicizing it would reveal a potentially embarrassing lack of control over its arms exports and the actions of its client states.

B. Weighing the Evidence: Egypt vs. Iraq

When comparing the two strongest candidates, Egypt and Iraq, both present compelling arguments:

- Arguments for Egypt:

- By 1959, Egypt had a well-established, deep, and multifaceted relationship with Yugoslavia. This included close personal ties between President Nasser and President Tito, shared leadership in the Non-Aligned Movement, and frequent high-level diplomatic consultations, including visits by both leaders to each other’s countries in 1959.4 Such a strong foundation of trust and mutual understanding would be highly conducive to arranging a secret arms transfer.

- Egypt was a very significant recipient of Soviet arms from 1955 onwards and would have possessed substantial stocks of AK-47s by 1959.2

- The precedent of Egypt reportedly facilitating the transfer of Yugoslav arms to Algerian rebels in 1954 demonstrates a historical willingness and capability to engage in complex, discreet arms movements in cooperation with Yugoslavia.4

- Arguments for Iraq:

- Iraq’s relationship with Yugoslavia was newer but developing rapidly in the crucial 1958-1959 period. The establishment of diplomatic relations in 1958 was quickly followed by a Trade and Cooperation Agreement that came into force in February 1959.30 This formal framework for interaction was in place at the time of the AK-47 deal.

- Following its 1958 revolution, Iraq became a recipient of Soviet arms and was actively seeking to diversify its international partnerships beyond its former Western patrons.3 A deal with a prominent non-aligned country like Yugoslavia would fit this new foreign policy orientation.

- The new revolutionary government in Baghdad might have been motivated by political solidarity, financial gain, or a desire to quickly establish Iraq as an independent actor on the regional stage.

While both nations are strong candidates, Egypt appears to hold a slight edge. The depth and maturity of its political relationship with Yugoslavia by 1959, coupled with the precedent for cooperation in sensitive arms transfers, make it a particularly compelling possibility. However, the confluence of Iraq’s recent political transformation, its immediate embrace of Soviet military aid, and the formalization of ties with Yugoslavia in early 1959 make it an almost equally plausible source. The critical factors are the combination of access to Soviet-supplied AK-47s and a motive or willingness to transfer approximately 2,000 of them to Yugoslavia under conditions of secrecy.

Logistical considerations, though not detailed in the available materials, would also have played a role. The transfer of 2,000 rifles and their ammunition is not a trivial undertaking. Both Egypt and Iraq, being Middle Eastern nations, share maritime proximity with Yugoslavia via the Mediterranean Sea. Existing trade routes (e.g., Yugoslav timber for Egyptian cotton mentioned in 4, or the general trade agreement with Iraq 30) could have provided cover for such shipments, perhaps disguised as other goods or moved through less scrutinized channels.

C. Limitations of the Provided Material

It is crucial to acknowledge that the available research documentation, while extensive, does not contain a definitive, explicit statement from an undeniable primary source (such as a declassified Yugoslav, Soviet, Egyptian, or Iraqi government document or a direct admission from a key participant) that unequivocally names the country involved in this specific 1959 AK-47 transfer to Yugoslavia. The identification process relies heavily on interpreting C.J. Chivers’ well-regarded but singular claim regarding this transaction, and then constructing a circumstantial case based on the known patterns of Soviet arms supplies and Yugoslav foreign relations during the specified period.

The successful execution of this secret purchase likely had a reinforcing effect on Yugoslavia’s broader strategy of acquiring foreign military technology through various means, including reverse engineering. It would have demonstrated the feasibility of such clandestine operations and underscored the value of cultivating diverse international relationships to achieve strategic defense objectives, ultimately contributing to the growth and capabilities of its significant domestic arms industry.6

VI. Conclusion: Assessing the Probabilities and the Lingering Mystery

A. Summary of Findings

The evidence strongly supports the claim, primarily advanced by C.J. Chivers, that in late 1959, Yugoslavia secretly purchased approximately 2,000 “early pattern” Soviet AK-47 assault rifles from an unnamed “Third World nation” that was itself a recipient of Soviet military aid.1 This acquisition was a critical step for Zastava Arms, providing the necessary physical examples to successfully reverse-engineer the Kalashnikov design, leading directly to the development and subsequent mass production of the Zastava M70 assault rifle, a cornerstone of Yugoslav military armament.

B. The Most Plausible Candidate(s)

Based on a comprehensive analysis of Soviet arms distribution patterns in the late 1950s, Yugoslav foreign relations, and specific chronological markers, Egypt emerges as the most plausible candidate for the role of the unnamed intermediary.

Key factors supporting this assessment include:

- Its status as a major recipient of Soviet weaponry, including AK-47s, by 1959.2

- The exceptionally close political and diplomatic ties between Yugoslavia and Egypt, exemplified by their joint leadership in the Non-Aligned Movement and reciprocal presidential visits in 1959.4

- A documented precedent of Egypt facilitating complex arms transfers involving Yugoslavia.4

Iraq stands as another strong contender. The 1958 revolution brought a new regime to power that rapidly sought Soviet military assistance and established diplomatic and trade relations with Yugoslavia in early 1959, making the timeline and political context feasible for such a transaction.3 The new Iraqi government may have seen this as an opportunity to solidify new alliances or gain other advantages.

Without more explicit, declassified documentary evidence directly naming the nation in the context of this specific 1959 AK-47 transaction, a definitive identification remains an educated deduction based on the available circumstantial evidence rather than an absolute certainty.

C. The Enduring Nature of the “Unnamed” Nation

The continued anonymity of the supplier nation in most historical accounts, with Chivers’ work being a notable exception in detailing the event itself, underscores the initial success of the secrecy surrounding the deal. This secrecy was vital for all parties involved: Yugoslavia needed to protect its non-aligned stance and its complex relationship with the USSR; the supplier nation needed to avoid Soviet repercussions for re-transferring arms; and the USSR itself may have preferred the transaction to remain unpublicized. This episode highlights the intricate and often opaque nature of Cold War diplomacy, where non-aligned nations frequently resorted to clandestine means to achieve their strategic security objectives while navigating the treacherous currents between the superpowers.

D. Implications for Yugoslav Arms Self-Sufficiency

This successful, albeit covert, acquisition of a significant quantity of AK-47s was a landmark achievement for Yugoslavia’s burgeoning defense industry. It directly enabled Zastava Arms to overcome the hurdles of reverse engineering and eventually mass-produce the Zastava M70. This rifle not only equipped the Yugoslav People’s Army but also became a notable export product, reflecting Yugoslavia’s determined pursuit of military self-reliance and its capacity for indigenous arms development.1

The very fact that this inquiry is prompted by a specific passage in a relatively recent historical work (Chivers’ The Gun, published in 2011) suggests that this particular detail of Cold War arms proliferation may still be emerging from historical obscurity. The Cold War was characterized by extensive secrecy, and archives from that period are continually being declassified and re-examined by historians. It is plausible that the “unnamed” status of the intermediary nation persists simply because the specific documents, testimonies, or archival records that could provide definitive confirmation have not yet entered the public domain or been widely analyzed. Future archival research in Yugoslav (now Serbian and other successor states’), Russian, Egyptian, Iraqi, or other relevant national archives could one day yield a conclusive answer.

Ultimately, the story of Yugoslavia’s 1959 secret AK-47 purchase serves as a compelling microcosm of the broader phenomenon of Kalashnikov proliferation. It illustrates that the global spread of this iconic weapon was not solely due to direct state-to-state transfers from the Soviet Union or licensed production by its allies. Secondary and tertiary movements of these arms, through various overt and covert channels and involving a diverse range of state and non-state actors, played a crucial role in the AK-47 achieving its unparalleled global ubiquity.10 This particular transaction demonstrates the resourcefulness of a non-aligned state in securing vital defense technology and the complex, often hidden, networks that facilitated the movement of arms during the Cold War.

Author’s Comment

This question intrigued me because Yugoslavia needed more AK-47 Type III samples to reverse engineer their milled M70s. To investigate this question, I ran a number of searches and scenarios and it is my opinion based on what I found that the most likely country was Egypt with Iraq being a less likely second. To be clear, I can’t guarantee it, but the odds favor Egypt given the factors indentified. I was once told that “It’s surprising how little history we really know” and this is an example of an event in recent history where we may never know the details.

Image Sources

The map of the Middle East in 1959 was generated by the author using Sora. The intent was to mainly show Egypt, Saudia Arabia, Iraq and Iran to give some geographical context.

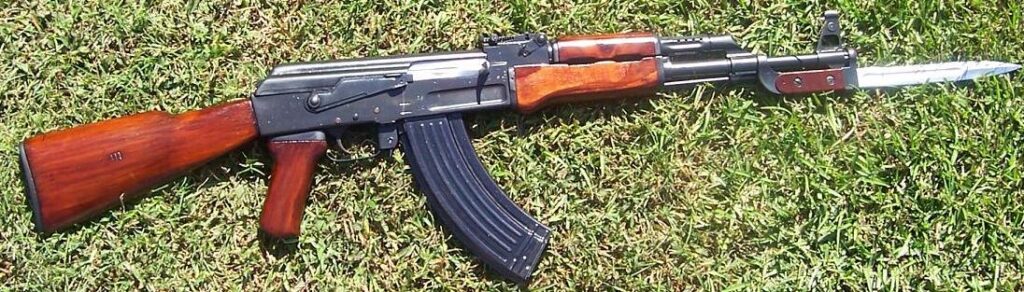

Russian AK-47 Type III (Photo by Gunrunner123 shared on Wikimedia)

The first ever meeting between Josip Broz Tito and Gamal Abdel Nasser – onboard the Yugoslav ship Galeb in the Suez Canal (1955). (Photo from the Online Museum of Syrian History, Shared on Wikimedia.

President Gamal Abdul Nasser and Yugoslavian President Josip Tito in Aleppo in 1959 / From left to right: United Arab Republic Vice President Akram al-Hawrani, the Aleppo industrialist Sami Saem al-Daher, director of Egyptian Intelligence Salah Nasr, President Josip Tito, his wife Jovanka Broz, President Gamal Abdul Nasser. The photo was taken in the home of Sami Saeb al-Daher, who was nationalized by President Nasser and left in bankrupcy in 1960 (Photo from the Online Museum of Syrian History, Shared on Wikimedia.

Works cited

- Zastava M70 assault rifle – Wikipedia, accessed May 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zastava_M70_assault_rifle

- SOVIET MILITARY AID TO THE UNITED ARAB REPUBLIC, 1955-66 (RR IR 67-9) – CIA, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/DOC_0000496350.pdf

- Russia Reemerging as Weapons Supplier to Iraq – The Jamestown Foundation, accessed May 11, 2025, https://jamestown.org/program/russia-reemerging-weapons-supplier-iraq/

- Egypt–Yugoslavia relations – Wikipedia, accessed May 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egypt%E2%80%93Yugoslavia_relations

- Yugoslavia and the Non-Aligned Movement – Wikipedia, accessed May 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yugoslavia_and_the_Non-Aligned_Movement

- 60. Interdepartment Policy Paper Prepared by the Departments of State and Defense, Washington, undated. (7/5/73), accessed May 11, 2025, https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/frus/nixon/e15/107794.htm

- YUGOSLAV MILITARY EQUIPMENT AND ITS SOURCES – CIA, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP79T00429A001100010022-0.pdf

- Guns in Movies, TV and Video Games – AK-47 – Internet Movie Firearms Database, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.imfdb.org/wiki/AK-47

- AK-47 | Definition, History, Operation, & Facts – Britannica, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/technology/AK-47

- www.macalester.edu, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.macalester.edu/russian-studies/about/resources/miscellany/ak47/#:~:text=Recognizing%20its%20demand%20in%20developing,being%20sold%20exclusively%20to%20governments.

- AK 47 – Russian Studies – Macalester College, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.macalester.edu/russian-studies/about/resources/miscellany/ak47/

- The Gun (Chivers book) – Wikipedia, accessed May 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Gun_(Chivers_book)

- The Gun by C.J. Chivers | Goodreads, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/7775851-the-gun

- The Gun – CJ Chivers – Amazon.com, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.amazon.com/Gun-C-J-Chivers/dp/0743270762

- The Gun By C.j. Chivers Summary PDF – Bookey, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.bookey.app/book/the-gun-by-c-j-chivers

- The Gun | Book by C. J. Chivers | Official Publisher Page – Simon & Schuster, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-Gun/C-J-Chivers/9780743271738

- THE GUN – Kirkus Reviews, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/cj-chivers/the-gun/

- AK-47 History – C.J. Chivers The Gun Excerpt – Esquire, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.esquire.com/news-politics/a25677/ak-47-history-1110/

- ОРУЖИЕ ДЛЯ ПРОФИ – Українська Спілка ветеранів Афганістану (воїнів-інтернаціоналістів), accessed May 11, 2025, http://www.usva.org.ua/mambo3/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=337

- AKM – Wikipedia, accessed May 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AKM

- How did the Middle East get a hold of Russian firearms like the AK-47 and RPG-7? – Quora, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.quora.com/How-did-the-Middle-East-get-a-hold-of-Russian-firearms-like-the-AK-47-and-RPG-7

- The Avtomat Kalashnikov Model of Year 1947 – Sites at Penn State, accessed May 11, 2025, https://sites.psu.edu/jlia/the-avtomat-kalashnikov-model-of-year-1947/

- Methodology: Kalashnikov & Variant Factory Dataset (1947-present) – Audrey Kurth Cronin, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.audreykurthcronin.com/p2p-pvid/p2p-pvid-kalashnikov/kalashnikov-variant-factory-dataset-1947-present/methodology-kalashnikov-variant-factory-dataset-1947-present/

- األسلحة الصغيرة – Small Arms Survey, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/sites/default/files/2021-09/SAS-HB-06-Weapons-ID-ch3-ARA.pdf

- Egyptian–Czechoslovak arms deal – Wikipedia, accessed May 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian%E2%80%93Czechoslovak_arms_deal

- Группа советских военных специалистов в Египте – Википедия, accessed May 11, 2025, https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%93%D1%80%D1%83%D0%BF%D0%BF%D0%B0_%D1%81%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B5%D1%82%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D1%85_%D0%B2%D0%BE%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%BD%D1%8B%D1%85_%D1%81%D0%BF%D0%B5%D1%86%D0%B8%D0%B0%D0%BB%D0%B8%D1%81%D1%82%D0%BE%D0%B2_%D0%B2_%D0%95%D0%B3%D0%B8%D0%BF%D1%82%D0%B5

- شاهد بالصور والفيديو: بعد وفاة مصممه “اليوم” ما هو سلاح الكلاشنكوف ومن هو ميخائيل كلاشنكوف القائل: “أنا لا اقتل ولكن يقتل من يضغط زنادي” – دنيا الوطن, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.alwatanvoice.com/arabic/news/2013/12/23/476461.html

- Odnosi Jugoslavije i Egipta — Википедија, accessed May 11, 2025, https://sr.wikipedia.org/sr-el/%D0%9E%D0%B4%D0%BD%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%B8_%D0%88%D1%83%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%B8%D1%98%D0%B5_%D0%B8_%D0%95%D0%B3%D0%B8%D0%BF%D1%82%D0%B0

- العلاقات المصرية اليوغوسلافية – ويكيبيديا, accessed May 11, 2025, https://ar.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%82%D8%A7%D8%AA_%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%B5%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A9_%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%8A%D9%88%D8%BA%D9%88%D8%B3%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%81%D9%8A%D8%A9

- Iraq–Yugoslavia relations – Wikipedia, accessed May 11, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iraq%E2%80%93Yugoslavia_relations

- العلاقات العراقية اليوغوسلافية – ويكيبيديا, accessed May 11, 2025, https://ar.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%82%D8%A7%D8%AA_%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%82%D9%8A%D8%A9_%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%8A%D9%88%D8%BA%D9%88%D8%B3%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%81%D9%8A%D8%A9

- Революция в Ираке 1958 г. И изменение ситуации на Ближнем Востоке – КиберЛенинка, accessed May 11, 2025, https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/revolyutsiya-v-irake-1958-g-i-izmenenie-situatsii-na-blizhnem-vostoke

- القوة البرية العراقية – ويكيبيديا, accessed May 11, 2025, https://ar.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%82%D9%88%D8%A9_%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A8%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A9_%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%82%D9%8A%D8%A9

- Syrian Civil War: WWII weapons used – wwiiafterwwii – WordPress.com, accessed May 11, 2025, https://wwiiafterwwii.wordpress.com/2017/06/27/syrian-civil-war-wwii-weapons-used/

- Russia’s arms exports to Indonesia top USD 2.5 billion over 25 years – Army Recognition, accessed May 11, 2025, https://armyrecognition.com/news/army-news/army-news-2018/russia-s-arms-exports-to-indonesia-top-usd-2-5-billion-over-25-years

- THE SOVIET-CUBAN CONNECTION IN CENTRAL AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN – CIA, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP88B00745R000100140026-6.pdf

- Soviet Arms Transfers to Sub-Saharan Africa: What are they Worth in the United Nations? – DTIC, accessed May 11, 2025, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA212065.pdf

- YUGOSLAVIA, MIDDLE EAST AND CREATION OF THE NON-ALIGNED MOVEMENT Текст научной статьи по специальности – КиберЛенинка, accessed May 11, 2025, https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/yugoslavia-middle-east-and-creation-of-the-non-aligned-movement

- The World’s Most Popular Gun – The New Atlantis, accessed May 11, 2025, https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/the-worlds-most-popular-gun