The modernization of the United States Army’s infantry forces has largely been defined by the transition from analog, voice-centric command structures to digital, network-centric operations. This paradigm shift, often categorized under the umbrella of “Soldier Lethality,” posits that the individual rifleman is no longer merely a combatant but a highly integrated sensor and shooter node within a broader battle network. Central to this transformation is the requirement for seamless data exchange between the soldier’s equipment—weapon sights, night vision goggles, tactical radios, and end-user computing devices. Historically, this connectivity was achieved through physical cabling, a solution that introduced significant snag hazards, durability issues, and logistical burdens during the Land Warrior and early Nett Warrior experiments.1

To resolve the “tyranny of wires,” the US Army Program Executive Office (PEO) Soldier developed the Intra-Soldier Wireless (ISW) architecture. ISW is designed to be the invisible digital backbone of the modern soldier, a secure, high-bandwidth Body Area Network (BAN) capable of streaming high-definition video and command data between devices without the physical tether. It represents a critical subsystem in flagship modernization programs, including the Integrated Visual Augmentation System (IVAS) and the Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW) Fire Control (XM157).2

However, the transition to wireless connectivity in the tactical edge environment introduces new and profound vulnerabilities. This report provides an exhaustive technical and operational analysis of the ISW protocol. It examines the architectural decisions—specifically the reliance on the ECMA-368 Ultra-Wideband (UWB) standard—and evaluates the system’s performance against the rigors of combat and the growing threat of sophisticated electronic warfare (EW) capabilities fielded by near-peer adversaries, notably the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of China.

2. Technical Architecture and Engineering Specifications

The ISW is not a single radio but a complex ecosystem comprising a physical radio frequency (RF) layer, a proprietary network protocol stack known as SolNet, and a series of hardware embedment standards. This architecture was selected after a rigorous Analysis of Alternatives (AoA) that weighed the competing demands of data throughput, power consumption, and Low Probability of Detection (LPD).4

2.1 The Physical Layer: Ultra-Wideband (UWB) and ECMA-368

The foundation of the ISW architecture is Ultra-Wideband (UWB) technology. Unlike conventional narrowband tactical radios (e.g., SINCGARS or Soldier Radio Waveform) that transmit high power over a narrow frequency slice, UWB transmits extremely low-power pulses over a massive bandwidth. The Army specifically selected the ECMA-368 standard (also known as WiMedia) for the ISW physical layer.2

2.1.1 Spectral Characteristics and Waveform

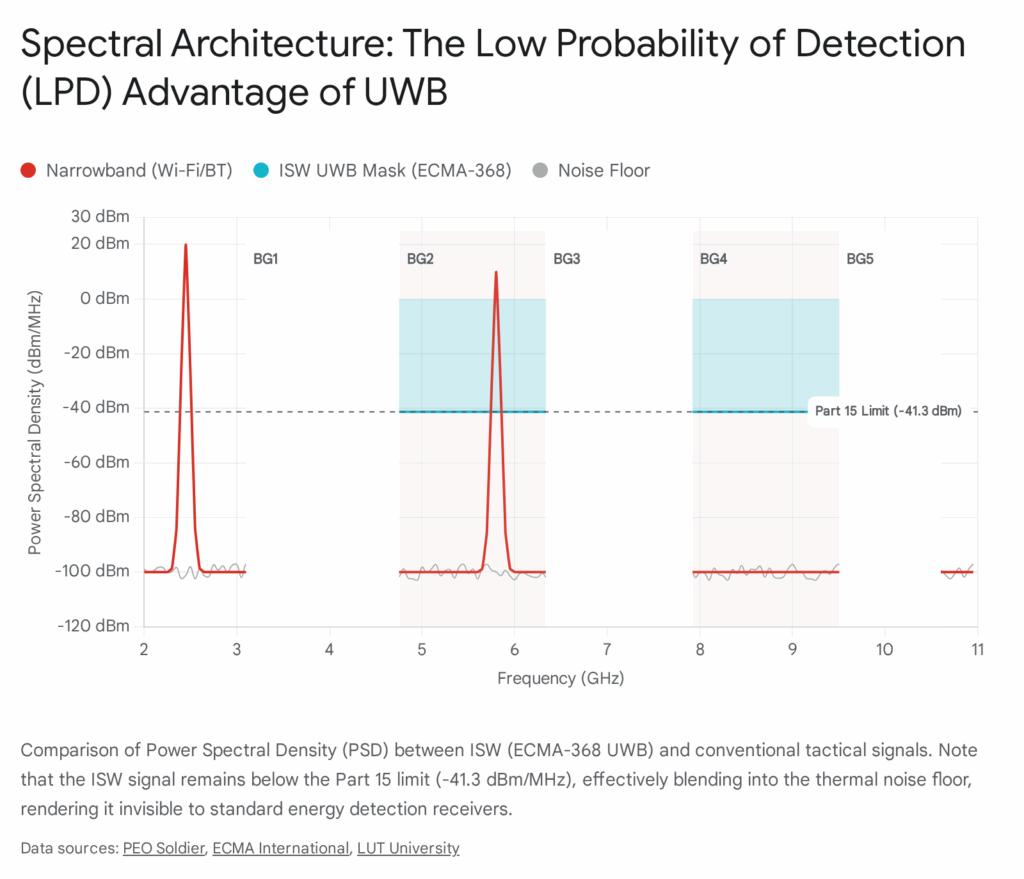

The ECMA-368 standard operates in the unlicensed spectrum between 3.1 GHz and 10.6 GHz. This vast 7.5 GHz of spectrum is divided into 14 bands, each with a bandwidth of 528 MHz.6 The operational logic behind this selection is threefold:

- Low Probability of Detection (LPD): The defining characteristic of UWB is its strict power spectral density (PSD) limit. ISW transmissions are regulated to remain below -41.3 dBm/MHz, effectively burying the signal beneath the thermal noise floor of conventional narrowband receivers. To a standard enemy listening station, an ISW transmission appears indistinguishable from background static, theoretically allowing a squad to operate electronically “silent” even while exchanging data.2

- High Throughput: The wide channel bandwidth enables extremely high data rates, essential for the system’s primary use case of streaming real-time thermal video from a weapon sight to a goggle. ECMA-368 supports data rates up to 480 Mbps at short ranges (less than 3 meters), significantly outperforming Bluetooth Low Energy (2 Mbps) or Zigbee, which lack the bandwidth for low-latency video.8

- Multipath Resilience: The waveform utilizes Multiband Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing (MB-OFDM). This modulation scheme allows the system to “hop” between frequency bands (Time-Frequency Interleaving), providing resilience against frequency-selective fading and narrowband interference. If a specific 528 MHz band is jammed or crowded, the system can theoretically maintain connectivity by utilizing the remaining bands.6

2.1.2 The 60GHz Alternative vs. UWB

During the development phase, the Army Analysis of Alternatives considered 60 GHz (mmWave) technologies, such as IEEE 802.11ad. While 60 GHz offers even higher data rates and excellent LPD due to atmospheric oxygen absorption, it was ultimately rejected in favor of UWB. The primary driver for this decision was body shadowing. Millimeter waves at 60 GHz are easily blocked by the human body; a soldier turning their back to a device would sever the connection. The lower microwave frequencies of UWB (3.1 GHz) offer superior diffraction characteristics, allowing signals to “bend” slightly around the soldier’s torso and armor plates, maintaining the link between a chest-mounted computer and a back-mounted radio.4

2.2 The SolNet Protocol Stack

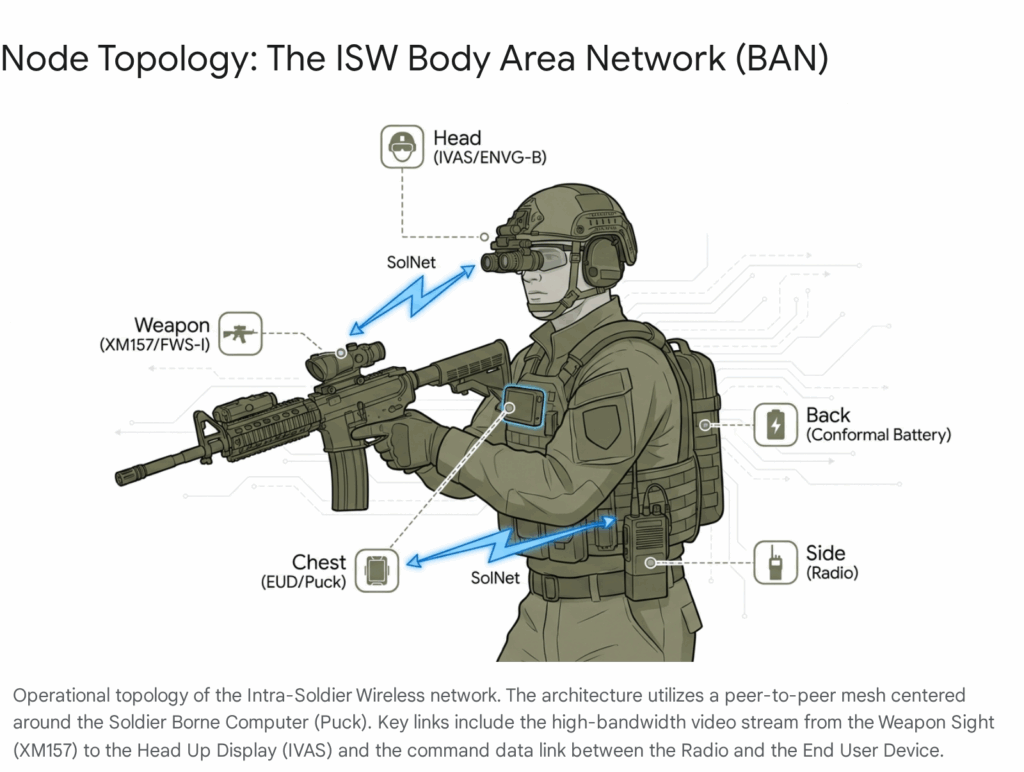

While ECMA-368 defines how the radio pulses travel, the intelligence of the system resides in SolNet (Soldier Network). This is the Army-owned, proprietary networking protocol stack that manages the Body Area Network (BAN). Defined in documents such as the ISW SolNet Protocol Specification (A3309776) 2, SolNet replaces the plug-and-play functionality of USB cables with a wireless equivalent.

2.2.1 Network Topology and Discovery

SolNet creates a localized “piconet” centered on the individual soldier. The protocol supports a network size of 2 to 14 devices per soldier, sufficient to connect the standard suite of infantry electronics.2 Unlike standard Wi-Fi, which relies on a central access point, SolNet operates on a distributed peer-to-peer basis, though the End User Device (EUD) or Soldier Borne Computer (“Puck”) typically acts as the coordinator.

The protocol handles the dynamic entry and exit of devices. For example, if a soldier drops their weapon (severing the link to the weapon sight) and then retrieves it, SolNet automatically handles the re-discovery and authentication of the sight without user intervention. The system scans for device descriptors to determine capabilities; if a peer device advertises a specific descriptor (ID 0x010D), the node recognizes it as capable of responding to Keep-Alive requests, maintaining network health.11

2.2.2 Quality of Service (QoS) for Lethality

In a combat environment, not all data is equal. A “fire” command from a digital trigger or a target handoff from a thermal sight is mission-critical, whereas a battery status report is not. SolNet implements strict Quality of Service (QoS) mechanisms to prioritize lethal data. Implementers must encode the QoS needs of each endpoint using advertised Endpoint Descriptors.11 This ensures that high-bandwidth, low-latency video streams (Required Throughput: 64–384 kbps for video, significantly higher for raw thermal feeds) are given priority over latency-tolerant traffic like short text messages (1.2–9.6 kbps) or email.12

2.3 Security and Encryption Standards

Given that ISW broadcasts tactical data, security is paramount to prevent interception or spoofing. The security architecture has evolved through two distinct generations, driven by requirements from the National Security Agency (NSA) to protect Secure but Unclassified (SBU) data at the tactical edge.

- Gen I ISW (2019): These modules utilized AES 128-bit encryption and achieved NIST FIPS 140-2 certification in 2019.

- Gen II ISW (2022): The current standard utilizes AES 256-bit encryption, achieving NIST certification in 2022.

- Secret Classification: The Army is actively working with the NSA (Memorandum CATS 2016-9843) to certify the Gen II modules for Secret and Below (SAB) data. This would allow classified intelligence (e.g., satellite imagery or specific threat warnings) to be transmitted wirelessly from the secure radio to the soldier’s display, a capability currently restricted by policy to wired connections only.2

3. Operational Integration and Use Cases

The operational value of ISW is derived from its integration into the “Soldier as a System” concept. It is the enabler for the Army’s most advanced night vision and fire control programs.

3.1 The “Connected Soldier” Ecosystem

The ISW module is an embedded subsystem, meaning it is physically integrated into the circuit boards of host devices rather than existing as a standalone dongle. The primary nodes in this ecosystem include:

- The Eyes (IVAS / ENVG-B): The Integrated Visual Augmentation System (IVAS) and the Enhanced Night Vision Goggle-Binocular (ENVG-B) serve as the primary display. They receive data streams via ISW to display augmented reality overlays, navigation waypoints, and video feeds.13

- The Weapon (NGSW-FC / FWS-I): The XM157 Fire Control (mounted on the Next Generation Squad Weapon) and the Family of Weapon Sights – Individual (FWS-I) (mounted on M4s) are the primary sensors. They generate the thermal imagery and ballistic data that must be transmitted to the eye.3

- The Brain (EUD / Puck): The Samsung Galaxy smartphone (EUD) running the Android Tactical Assault Kit (ATAK), often connected to a “Puck” or Mission Planning Computer, serves as the central processor. It fuses GPS data, map overlays, and Blue Force Tracking (BFT) icons.1

The Voice (Radio): Tactical radios like the AN/PRC-163 or AN/PRC-148C provide the long-haul link to the squad leader and platoon. ISW connects the radio to the EUD, allowing the soldier to send text messages and coordinates over the radio network using the phone interface.16

3.2 Rapid Target Acquisition (RTA): The Killer App

The primary lethal application of ISW is Rapid Target Acquisition (RTA). This capability creates a wireless bridge between the weapon sight and the goggle.

- Mechanism: The thermal image from the weapon sight is encoded and streamed via SolNet to the soldier’s HUD. The system superimposes the weapon’s reticle onto the soldier’s field of view.

- Tactical Advantage: This allows a soldier to engage targets without achieving a traditional cheek weld. More importantly, it enables “shooting around corners”—a soldier can expose only their hands and rifle from behind cover, view the target through the goggle via the wireless feed, and engage accurately while their head and body remain fully protected. This capability was deemed “transformational” in early assessments, but relies entirely on the stability of the ISW link.15

4. Operational Performance and Reliability Analysis

Despite the theoretical capabilities of the ISW architecture, operational testing has revealed significant reliability challenges. The transition from controlled laboratory environments to the chaotic reality of field maneuvers has exposed the fragility of the UWB link.

4.1 The Reliability Crisis in Operational Testing

Recent reports from the Director, Operational Test and Evaluation (DOT&E) paint a concerning picture of the system’s reliability in combat-realistic scenarios.

4.1.1 XM157 and NGSW Critical Failures

The integration of ISW into the XM157 Fire Control for the Next Generation Squad Weapon has been problematic. In operational demonstrations conducted in 2023 and 2024, the system demonstrated a “low probability of completing one 72-hour wartime mission without a critical failure”.18 Soldiers involved in the testing rated the usability of the XM157 as “below average/failing.”

While the unclassified reports do not isolate the specific failure mode, the “critical failures” in a networked optic strongly implicate the wireless subsystem. The XM157 relies on ISW to receive environmental data (wind speed from a separate sensor or EUD) and to communicate with the ballistic solver. A disconnection or high-latency spike disrupts the fire control solution, effectively turning a sophisticated “smart” optic into a heavy conventional scope.

4.1.2 IVAS 1.0 Performance Shortfalls

The IVAS 1.0 operational test in June 2022 further highlighted the limitations of the wireless architecture. Soldiers reported that the system was unreliable, with frequent connectivity drops that led to a loss of situational awareness. The system failed to demonstrate improvements over existing equipment, with soldiers hitting fewer targets and engaging more slowly when using IVAS compared to standard optics.20

The reliability issues were compounded by physical symptoms; soldiers reported disorientation, dizziness, and nausea.13 While some of this is attributable to the heads-up display optics, latency in the ISW video stream (lag between weapon movement and reticle movement on the display) is a known cause of “simulator sickness” in augmented reality systems.

4.2 The Physics of Failure: Body Shadowing and Multipath

The root cause of these reliability issues is often the physics of the chosen frequency band. While UWB at 3.1-10.6 GHz penetrates clothing, it is heavily attenuated by the human body—a mass of water and tissue that absorbs microwave energy.

- Body Shadowing: When a soldier holds their rifle across their chest (the “high ready” or “patrol” position), their own torso acts as a barrier between the weapon-mounted ISW node and the back-mounted radio or battery. This “self-shadowing” can cause signal attenuation of 20-30 dB, frequently severing the link.4

- Multipath Interference: In complex environments like the interior of a Stryker infantry carrier or inside a concrete building, the UWB pulses bounce off metal surfaces, creating severe multipath environments. While SolNet’s RAKE receivers are designed to harvest this energy, extreme multipath can cause destructive interference and packet loss.

- Spectrum Congestion: The ISW is designed to support 14 devices per soldier, and has been tested with 15 soldiers in a 25-square-foot area.2 However, scaling this to a platoon (30+ soldiers) or a company operation creates a “near-far” problem where the aggregate noise floor of hundreds of UWB transmitters degrades the effective range and throughput of the network.

4.3 The Power Penalty

The reliance on wireless connectivity has also exacerbated the soldier’s power burden. Continuous transmission of high-bandwidth video via UWB is energy-intensive.

- Battery Logistics: A Nett Warrior-configured squad requires approximately 19 Conformal Wearable Batteries (CWBs) (totaling 50 pounds) to sustain operations for 72 hours. In contrast, a fully connected squad utilizing earlier, less efficient configurations would require up to 60 CWBs (156 pounds) for the same duration.22

- Thermal Load: The power consumption of the ISW module also generates heat. In thermal sights like the XM157 or FWS-I, this heat generation can degrade sensor performance or contribute to thermal shutdown in hot environments.

5. Adversarial Disruption: The Strategic Threat from China

The most critical question regarding ISW is its survivability against a peer adversary. While the system’s Low Probability of Detection (LPD) is effective against insurgents, it faces a profound threat from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), which views the electromagnetic spectrum as a primary domain of warfare.

5.1 PLA Electronic Warfare Doctrine

The PLA operates under the doctrine of “Integrated Network Electronic Warfare” (INEW), which fuses cyber warfare and electronic jamming into a unified offensive capability.23 The PLA has established specialized research institutes dedicated to countering US tactical datalinks.

- 29th Research Institute (SWIEE): Located in Chengdu, this institute is the primary developer of electronic intelligence (ELINT) and radar jamming systems.

- 36th Research Institute: Located in Hefei, this institute specializes in communications jamming.24

These institutes have moved beyond general jamming and are actively researching specific countermeasures against UWB and LPD waveforms.

5.2 Specific Vulnerabilities to Jamming

Technical analysis of Chinese defense research publications indicates a matured capability to detect and disrupt ECMA-368 UWB signals.

5.2.1 Wideband Noise Jamming

UWB receivers have, by definition, a very wide “front end” to capture the 528 MHz bandwidth pulses. This makes them susceptible to high-power wideband noise jamming. A PLA jammer does not need to decrypt the SolNet signal; it simply needs to broadcast high-power noise across the 3-5 GHz band. This raises the noise floor at the ISW receiver, blinding it to the low-power pulses of the soldier’s network and causing the protocol to time out.25

5.2.2 UWB Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) Attacks

A 2023 study by Chinese researchers 26 specifically investigated “Jamming technology of distributed ultra-wideband electromagnetic pulse to ground receivers.” The study utilized low-orbit satellites and drones to generate repetitive UWB electromagnetic pulses (0.7 ns width).

- Mechanism: The high-peak-power pulses drive the Low Noise Amplifier (LNA) of the target receiver into saturation (gain compression).

- Effect: Once saturated, the LNA cannot amplify the weak incoming signals from the friendly network. The receiver effectively goes deaf. The study concluded that this technique causes “temporary gain compression” sufficient to disrupt communications without permanently damaging the hardware, making it a highly effective “soft kill” tactic.26

5.2.3 6G and Terahertz EW

Recent developments in Chinese 6G technology include EW applications. Researchers claim to have developed 6G-based weapons capable of generating “3,600 false targets” and processing signals at speeds far exceeding current US capabilities. These systems, utilizing terahertz frequencies and advanced AI signal processing, pose a threat to the LPD characteristics of ISW by using deep learning to identify and isolate the statistical anomalies of UWB transmissions that would otherwise look like noise.27

5.3 The Timeline of Vulnerability

There is a disturbing correlation between the US Army’s fielding timeline for ISW and the publication of specific counter-measures by Chinese research institutes.

- 2019: US Army certifies Gen I ISW modules.

- 2022: PLA publishes research on “UWB Electromagnetic Pulse Jamming” specifically targeting receiver LNAs.26

- 2023: US Army fields Gen II ISW modules in NGSW prototypes.

- 2023: PLA announces 6G EW systems with advanced signal processing.27

This timeline suggests a reactive and adaptive adversarial posture, where specific US tactical waveforms are identified and targeted for negation before they reach Full Operational Capability (FOC).

6. Future Evolution and Mitigation Strategies

Recognizing the limitations of the current ECMA-368 architecture, the Army is pursuing an evolutionary path to harden the ISW ecosystem.

6.1 Hardware Hardening: Antenna Diversity

Immediate efforts focus on mitigating the physics of body blocking. The Army has released Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) topics for “Intra-Soldier Wireless Antenna Improvement”.29 The goal is to develop diversity antenna systems—integrating antennas into the front and back of the soldier’s vest and helmet.

- Dynamic Switching: The system would dynamically sense the link quality and switch to the antenna with the best Line of Sight to the target device, ensuring that the soldier’s body never completely blocks the signal path.

- SWaP Reduction: These initiatives also aim to reduce the Size, Weight, and Power (SWaP) of the antenna modules to facilitate integration into the conformal battery and vest structures.

6.2 Next Generation Waveforms: Cognitive Radio

Looking beyond ECMA-368, the Army is exploring Next Generation Narrowband Soldier Radio Waveforms and cognitive radio technologies.31

- Interference Avoidance: Unlike the static hopping of SolNet, future cognitive waveforms will use AI to sense the electromagnetic spectrum in real-time. If jamming is detected in the 3.5 GHz band, the system will automatically notch out that frequency and shift traffic to a clear band, potentially moving out of the microwave band entirely if necessary.

- MIMO Technology: Companies like Silvus Technologies are developing MIMO (Multiple Input Multiple Output) waveforms for the Army.32 MIMO uses multiple antennas to transmit multiple data streams simultaneously. Crucially, it turns the multipath problem (signals bouncing off walls) into an advantage, using the reflected signals to increase data throughput and link reliability in urban environments.

6.3 IVAS 1.2 and Software Refinement

The transition to IVAS 1.2 represents a software-centric evolution. The Army has acknowledged the reliability failures of IVAS 1.0 and is “restructuring” the program.34 This includes refining the SolNet protocol to be more tolerant of latency and implementing “graceful degradation” modes. Instead of a hard crash when the link quality drops, the system may degrade the video resolution or frame rate to maintain a heartbeat connection, preserving situational awareness even in a jammed environment.

7. Conclusion

The Intra-Soldier Wireless (ISW) protocol represents a bold engineering attempt to solve a persistent logistical problem—the cabling burden of the modern infantryman. By leveraging commercial UWB standards, the Army successfully demonstrated the capability to create a high-bandwidth, wireless body area network that can stream lethal fire control data.

However, the current iteration of ISW, built upon the ECMA-368 standard, faces a “validity gap” between its theoretical performance and its operational reality. The system is plagued by reliability issues driven by the fundamental physics of body shadowing and spectrum congestion, as evidenced by the critical failures in the XM157 and IVAS operational tests. More alarmingly, the system’s spectral sanctuary is eroding. The proliferation of advanced electronic warfare capabilities within the PLA—specifically the development of UWB pulse jamming and AI-driven signal detection—threatens to render the “stealthy” ISW network visible and vulnerable in a near-peer conflict.

While ISW fulfills the requirement of eliminating cables, it currently fails the paramount requirement of combat reliability. The path forward necessitates a rapid evolution away from static commercial standards toward dynamic, cognitive waveforms and hardware diversity that can survive the contested electromagnetic spectrum of the future battlefield.

Data Summary Tables

Table 1: ISW Technical Specifications

| Feature | Specification | Source |

| Protocol Name | SolNet (Soldier Network) | 2 |

| Physical Layer | ECMA-368 (WiMedia UWB) | 2 |

| Frequency Range | 3.1 GHz – 10.6 GHz | 5 |

| Bandwidth | 528 MHz per band (14 bands) | 6 |

| Throughput | Up to 480 Mbps (Range dependent) | 8 |

| Encryption | AES 256-bit (Gen II, NIST Certified) | 2 |

| Network Density | 2 to 14 devices per soldier | 2 |

| Power Density | -41.3 dBm/MHz (Part 15 Limit) | 2 |

Table 2: Key Integration Programs and Status

| Program | Role of ISW | Current Status | Reliability Issues | Source |

| IVAS | Streams video from weapon to HUD; AR data | IVAS 1.2 Prototyping | High; Motion sickness, connectivity drops | 13 |

| NGSW-FC (XM157) | Ballistic data, Wind sensor link | Field Testing | Critical Failures (Low prob. of 72h mission success) | 18 |

| Nett Warrior | Connects EUD (Phone) to Radio | Deployed / Sustaining | Power burden (Requires 19-60 CWBs) | 22 |

| FWS-I | Wireless Thermal Sight | Fielded | Susceptible to body blocking | 13 |

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- Nett Warrior Interconnect Architecture White Paper – DTIC, accessed December 27, 2025, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/AD1011122.pdf

- 202040130 Unclas PEO Soldier Reference Architecture v1.0, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.peosoldier.army.mil/Portals/53/Documents/soldier_systems/UNCLAS_PEO_Soldier_Reference_Architecture_v1_0.pdf

- PEO SOLDIER TECHNOLOGY COMPENDIUM, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.peosoldier.army.mil/Portals/53/Documents/soldier_systems/2025_PEO_Soldier_Technology_Compendium_Print.pdf

- Intra soldier wireless (ISW) – IEEE Xplore, accessed December 27, 2025, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/iel7/7460734/7465297/07465463.pdf

- ECMA-368, accessed December 27, 2025, https://ecma-international.org/publications-and-standards/standards/ecma-368/

- Diplomityö – LUTPub, accessed December 27, 2025, https://lutpub.lut.fi/bitstream/10024/30420/1/TMP.objres.522.pdf

- WIRELESS SECURITY STANDARDS – CWNP, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.cwnp.com/wp-content/uploads/pdf/BBP_Wireless_Security_Standards_VER_3_0.pdf

- History and Applications of UWB – IEEE Xplore, accessed December 27, 2025, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/iel5/5/4802183/04796278.pdf

- UWB or Bluetooth CS for positioning solutions – Electronic Specifier, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.electronicspecifier.com/products/communications/uwb-or-bluetooth-cs-for-positioning-solutions/

- Report: Ultrawideband dies by 2013 – EE Times, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.eetimes.com/report-ultrawideband-dies-by-2013/

- ISW Protocol Specification – AWS, accessed December 27, 2025, https://imlive.s3.amazonaws.com/Federal%20Government/ID432307301742870717393058329383741040/Attachment%2009%20ISW_SolNet_Protocol_FinalDraft.pdf

- Chapter: 6 Networks, Protocols, and Operations – National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.nationalacademies.org/read/5905/chapter/8

- Integrated Visual Augmentation System (IVAS) – Director Operational Test and Evaluation, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.dote.osd.mil/Portals/97/pub/reports/FY2022/army/2022ivas.pdf?ver=Vm9qh265-p4H71-SpIhrnA%3D%3D

- Vortex Gets $20 Million Contract for XM157 NGSW-FC Optic – Accurate Shooter Bulletin, accessed December 27, 2025, https://bulletin.accurateshooter.com/2022/02/vortex-gets-20-million-contract-for-xm157-ngsw-fc-optic/

- Nett Warrior gets new end-user device | Article – Army.mil, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.army.mil/article/107811/nett_warrior_gets_new_end_user_device

- Capability Program Executive Command, Control, Communications, and Network (CPE C3N) > Organizations > PM Tactical Network > Network Modernization > Secure Wireless – PEO C3N, accessed December 27, 2025, https://peoc3n.army.mil/Organizations/PM-Tactical-Network/Network-Modernization/Secure-Wireless/

- The 24 Programs the Army Promised to Expedite: Part Five — Training and Simulation, Night Vision – National Defense Magazine, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2023/10/6/the-24-programs-the-army-promised-to-expedite-part-five-training-and-simulation-night-vision

- Soldiers Give the Army’s New Rifle Optic Low Ratings – Military.com, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.military.com/daily-news/2025/02/04/armys-new-rifles-have-optic-problem.html

- US next-gen rifle shows reliability issues in combat simulation – Defence Blog, accessed December 27, 2025, https://defence-blog.com/us-next-gen-rifle-shows-reliability-issues-in-combat-simulation/

- Army Hopeful Troubled Headset Program Is Finally Looking Up, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.ntsa.org/news-and-archives/2024/4/2/army-hopeful-troubled-headset-program-is-finally-looking-up

- Budget Activity 3 – Justification Book – U.S. Army, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.asafm.army.mil/Portals/72/Documents/BudgetMaterial/2018/Base%20Budget/rdte/Budget%20Activity%203.pdf

- Soldier Tactical Power: – Fort Benning, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.benning.army.mil/Infantry/Magazine/issues/2020/Summer/pdf/3_Irwin-battery.pdf

- Killing Me Softly: Competition in Artificial Intelligence and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, accessed December 27, 2025, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/2053617/killing-me-softly-competition-in-artificial-intelligence-and-unmanned-aerial-ve/

- China’s Strategic Modernization: Implications for the United States – USAWC Press, accessed December 27, 2025, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1148&context=monographs

- Survey on Intentional Interference Techniques of GNSS Signals and Radio Links between Unmanned Aerial Vehicle and Ground Control Station – ResearchGate, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/397185883_Survey_on_Intentional_Interference_Techniques_of_GNSS_Signals_and_Radio_Links_between_Unmanned_Aerial_Vehicle_and_Ground_Control_Station

- Jamming technology of distributed ultra-wideband electromagnetic pulse to ground receivers based on low-orbit satellites – 强激光与粒子束, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.hplpb.com.cn/en/article/doi/10.11884/HPLPB202335.220225

- Chinese scientists develop the first 6G electronic warfare system – Matthew Griffin, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.fanaticalfuturist.com/2025/07/chinese-scientists-develop-the-first-6g-electronic-warfare-system/

- China tests AI radar to defeat electronic warfare jamming – Aerospace Global News, accessed December 27, 2025, https://aerospaceglobalnews.com/news/china-ai-radar-electronic-warfare/

- Department of Defense Fiscal Year (FY) 2025 Budget Estimates – Justification Book, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.asafm.army.mil/Portals/72/Documents/BudgetMaterial/2025/Base%20Budget/Research,%20Development,%20Test%20and%20Evaluation/RDTE%20-%20Vol%202%20-%20Budget%20Activity%204B.pdf

- Department of Defense Fiscal Year (FY) 2026 Budget Estimates – Justification Book – U.S. Army, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.asafm.army.mil/Portals/72/Documents/BudgetMaterial/2026/Discretionary%20Budget/rdte/RDTE%20-%20Vol%202%20-%20Budget%20Activity%204B.pdf

- TrellisWare Selected to Develop U.S. Army’s Next Generation Narrowband Soldier Radio Waveform, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.trellisware.com/trellisware-selected-to-develop-u-s-armys-next-generation-narrowband-soldier-radio-waveform/

- Next-Generation MIMO Research & Development | Wireless R&D – Silvus Technologies, accessed December 27, 2025, https://silvustechnologies.com/why-silvus/research-development/

- The Impact of LPI/LPD Waveforms and Anti-Jam Capabilities on Military Communications, accessed December 27, 2025, https://modernbattlespace.com/2020/09/24/impact-lpi-lpd-waveforms-anti-jam-capabilities-military-communications/

- Army accepts prototypes of the most advanced version of IVAS, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.army.mil/article/268702/army_accepts_prototypes_of_the_most_advanced_version_of_ivas

Nett Warrior – Executive Services Directorate, accessed December 27, 2025, https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/FOID/Reading%20Room/Science_and_Technology/16-F-0250_(REPORT)_Nett_Warrior_IOT&E_Report.pdf