Really, my experience with Yugo rifles began with the stamped M70 series. We’ve spent these last few posts providing the backstory, but how did Zastava move from the M64 to the M70 series? Let’s find out.

1. Introduction: Yugoslavia’s Independent Path to the Kalashnikov

In the complex geopolitical landscape following World War II, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, under the leadership of Marshal Josip Broz Tito, charted a course distinct from both the Western NATO alliance and the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact.1 This policy of non-alignment fostered a unique national identity but also necessitated a high degree of self-sufficiency, particularly in defense production.1 Central to this effort was the state-owned Zastava Arms (Zastava oružje) factory located in Kragujevac, Serbia. With roots tracing back to a cannon foundry established in the 1850s 2, Zastava oružje possessed a long and storied history of arms manufacturing for Serbia and later Yugoslavia.2

As the nature of warfare evolved in the mid-20th century, the limitations of traditional bolt-action rifles, like the Mauser patterns previously produced by Zastava 1, became apparent. Yugoslav military planners and engineers recognized the need for a modern assault rifle chambered for an intermediate cartridge. Early research in the 1950s involved studying captured German StG 44 rifles 1, but the future clearly lay with the design rapidly proliferating across the Eastern Bloc: the Kalashnikov AK-47.

However, due to the political rift between Belgrade and Moscow, Yugoslavia could not simply acquire a license to produce the AK-47, as many other nations did.1 Instead, Zastava embarked on an ambitious path of independent development through reverse engineering. The process began in earnest after 1959, when two Albanian border guards defected to Yugoslavia carrying Soviet-made AK-47s.1 These initial samples, while valuable, provided insufficient data for full reproduction. The effort received a significant boost when Yugoslavia covertly purchased a batch of 2,000 AK rifles from an unnamed African nation, which had originally received them as Soviet military aid.1 This allowed Zastava’s engineers – a team including Božidar Blagojević, Major Miloš Ostojić, Miodrag Lukovac, Milutin Milivojević, Milan Ćirić, Stevan Tomašević, Predrag Mirčić, and Mika Mudrić – to meticulously study the design and develop their own manufacturing processes.1

This independent development program, known as FAZ (Familija Automatika Zastava – Family of Zastava Automatic Weapons) 1, aimed to create a whole family of firearms based on the Kalashnikov operating principle. The culmination of the initial phase was the M64 series of prototypes. Building directly upon the lessons learned from the M64, Zastava refined the design to create the Automatska Puška M70 (AP M70), or Automatic Rifle Model 1970. Officially adopted that year, the M70 became the standard infantry weapon of the Jugoslovenska Narodna Armija (JNA – Yugoslav People’s Army) and represented a uniquely Yugoslavian interpretation of the Kalashnikov, distinct from its Soviet progenitor and other licensed copies.7

2. From Prototype to Production: The M64’s Legacy and the Birth of the M70

The Zastava M64, though never mass-produced in its original forms, served as the crucial stepping stone to the M70. The late M64 prototypes established several features that would become characteristic of the Yugoslav AK family. These included a robust milled receiver, heavily based on the Soviet AK Type 3 but featuring unique cosmetic differences like a distinctive raised step on the left side.7 The barrels were threaded into the receiver, similar to the early Soviet AKs, but were slightly thicker and, notably, were not chrome-lined.7

From the very beginning, Yugoslav engineers designed their Kalashnikov variant with the capability to launch rifle grenades, a feature deemed essential.1 The M64 incorporated an integral flip-up grenade sight, typically mounted on the gas block, which also functioned as a gas cut-off mechanism. When raised for firing grenades, the sight would block the gas port, preventing gas from cycling the action and ensuring all propellant force was directed to launching the grenade.1 Other distinctive M64 features included longer wooden handguards with three cooling vents instead of the usual two found on Soviet AKs 5, a unique hollow cylindrical charging handle borrowed from the Yugoslav M59 SKS rifle 1, and, on the M64B folding stock variant, an underfolding stock adapted from the M56 submachine gun.1

A particularly interesting feature of the M64 was its internal bolt hold-open (BHO) mechanism, housed within the receiver.7 This device automatically locked the bolt to the rear after the last round was fired, providing a clear visual and tactile indication that the weapon was empty. However, this internal BHO required specially modified AK magazines with a specific cut to function correctly.11

Despite satisfactory performance in field trials, the JNA did not adopt the M64 in large quantities.7 Military thinking, however, was evolving. Initial reluctance among some senior officers towards issuing automatic weapons to every soldier 1 gradually gave way, potentially influenced by observations of conflicts like the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, where Soviet troops were universally equipped with AK-pattern rifles.1 The push for a domestically produced automatic rifle gained momentum, leading the JNA to formally approve the Zastava design for serial production in 1970, designated as the AP M70.7

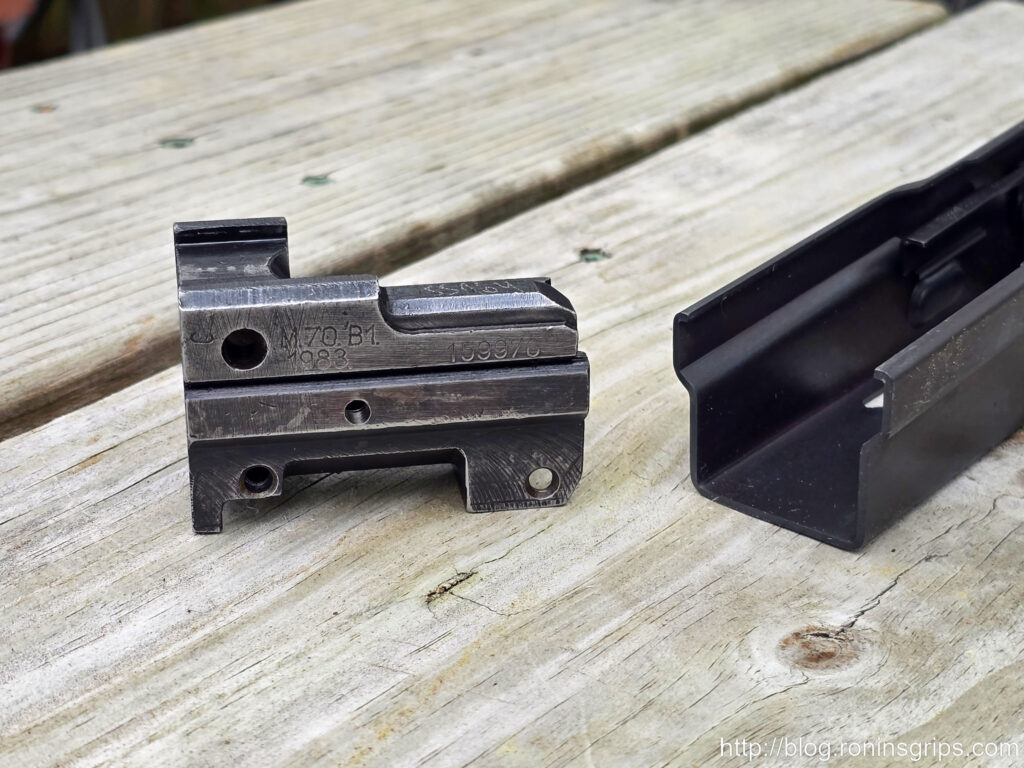

To prepare the design for mass production, Zastava implemented several key changes compared to the M64 prototypes. The most significant alteration was the removal of the M64’s internal, receiver-mounted bolt hold-open mechanism.7 While functionally desirable, the internal BHO added complexity and cost to receiver manufacturing. Zastava opted for a simpler, more cost-effective solution: transferring the BHO function entirely to the magazine. They designed proprietary M70 magazines equipped with follower plates that had flat rear edges. After the last round was fired, this flat edge on the follower would physically block the bolt from closing, achieving the hold-open function without requiring the complex internal linkage of the M64.7 This decision represented a classic engineering trade-off, prioritizing the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of rifle production by simplifying the receiver, while accepting the need for specific, slightly more complex magazines – a consumable item – to retain the desired BHO capability.

Many other features from the M64 were carried over directly into the initial M70 production models. These included the milled receiver construction, the integral grenade sight and gas cut-off system, the distinctive 3-slot handguards, and the non-chrome-lined barrel.7 The unique method of securing the dust cover using a locking recoil spring guide, crucial for preventing it from being dislodged during grenade launching, was also retained.7

3. The Milled Era: Early M70 Variants (M70, M70A, M70A1, M70B, M70AB)

The first Zastava rifles to enter widespread service with the JNA in 1970 were built on robust milled receivers.7 These early variants established the foundation of the M70 family:

- M70: The baseline model featured the milled receiver and a traditional fixed wooden stock.7

- M70A: This variant offered increased portability for airborne troops or vehicle crews by incorporating an underfolding metal stock, again paired with the milled receiver.7

These initial production M70 and M70A rifles shared the core characteristics inherited from the M64 program. Their milled receivers were patterned after the Soviet Type 3 AK-47 but possessed distinct Yugoslav features, most notably the smooth left side lacking the large lightening cut found on Soviet and many other milled AKs.7 Zastava also engraved serial numbers just above the magazine well, rather than on the front trunnion as was common Soviet practice.7 Initially, these rifles featured barrels that were threaded into the receiver 7, a strong but relatively labor-intensive method. They retained the integral grenade launching sight/gas cut-off, the 3-slot handguards, the non-chrome-lined barrels, and the unique locking dust cover system.7

Recognizing the growing importance of night vision and optical sights, Zastava soon introduced a variant specifically designed to accommodate them:

- M70A1: This model was essentially an M70A (milled receiver, underfolding stock) equipped with a factory-installed scope rail riveted to the left side of the receiver, allowing for the mounting of various optical or night sights.7

Shortly after the M70 series entered production, Zastava implemented a significant change to streamline manufacturing, even while still using milled receivers. They transitioned from the time-consuming process of threading barrels into the receivers to the faster and cheaper method of pressing the barrels into the receiver trunnion and securing them with a cross-pin.7 This change mirrored the production techniques already used for the Soviet AKM. Rifles produced with this updated barrel attachment method received new designations:

- M70B: Milled receiver, fixed stock, with a pressed-and-pinned barrel.7

- M70AB: Milled receiver, underfolding stock, with a pressed-and-pinned barrel.7

This relatively rapid adoption of pressed-and-pinned barrels, occurring before the eventual switch to stamped receivers, demonstrates Zastava’s proactive approach to optimizing production efficiency. It suggests that engineers were continuously evaluating and implementing cost-saving measures, likely learning from the initial M70 production runs or analyzing contemporary Soviet AKM manufacturing techniques, which had long utilized the press-and-pin method. This incremental optimization occurred even within the constraints of the more complex milled receiver production line.

4. The Stamped Revolution: The M70B1 and M70AB2

By the mid-1970s, seeking further reductions in production time and cost to meet military demands, Zastava followed the path previously taken by the Soviet Union and transitioned from milled receivers to stamped sheet metal receivers for the M70 family.7 However, the Yugoslav approach to the stamped receiver resulted in a design significantly different and more robust than the standard Soviet AKM.

The defining characteristic of the Zastava stamped receiver was its thickness. Instead of using the 1.0mm thick sheet steel common to the AKM and most of its derivatives, Zastava opted for a heavier 1.5mm thick stamping.11 Compounding this increase in strength, Zastava incorporated a front trunnion design based on the one used in the RPK light machine gun.7 The RPK trunnion is substantially larger and more robust than a standard AKM trunnion, designed to withstand the stresses of sustained automatic fire. To accommodate this larger RPK-style trunnion within the stamped receiver, Zastava introduced distinctive bulges on the forward section of the receiver, just ahead of the magazine well.7 These “bulged trunnion” receivers became a visual hallmark of the later M70 series and related weapons like the M72 RPK.

This combination of a 1.5mm thick receiver and an RPK-style bulged front trunnion resulted in an exceptionally durable rifle, significantly stronger and more rigid than a standard AKM.20 The decision to adopt this heavier construction for the standard infantry rifle, not just the squad automatic weapon, strongly suggests a deliberate design philosophy prioritizing extreme robustness and the ability to reliably handle the stresses of repeated rifle grenade launching, which remained a core requirement.7 This “overbuilding” came at the cost of increased weight compared to other AKM derivatives 9, but clearly aligned with Yugoslav military preferences.

The two primary variants featuring this heavy-duty stamped receiver construction became the workhorses of the JNA and subsequent forces:

- M70B1: Featured the 1.5mm stamped receiver with the bulged RPK-style trunnion and a fixed wooden stock.7 The stock on the M70B1 was often noted for being slightly longer than typical Warsaw Pact AKM stocks and frequently included a thick rubber buttpad, enhancing shooter comfort, particularly when launching grenades.10

- M70AB2: Combined the 1.5mm bulged trunnion stamped receiver with the practicality of an underfolding metal stock.7 This became one of the most widely produced and recognizable M70 variants.

Both the M70B1 and M70AB2 typically included flip-up night sights integrated into the standard iron sight blocks. These sights utilized either tritium vials (which glow continuously) or phosphorescent paint (which needs to be charged by a light source) for low-light aiming.7 They retained the integral grenade launching ladder sight and gas cut-off mechanism on the gas block 7 and continued the practice of using non-chrome-lined barrels for standard military production.7 The standard Yugoslav fire selector markings were present on the right side of the receiver: “U” for Ukočeno (Safe), “R” for Rafalna (Automatic fire), and “J” for Jedinačna (Semi-automatic fire).7

The persistent use of non-chrome-lined barrels throughout the main production run for the JNA stands in contrast to Soviet practice, where chrome lining was standard for AKMs to enhance barrel life and corrosion resistance. This Yugoslav decision was likely driven by cost considerations and potentially an established maintenance doctrine that emphasized frequent and thorough cleaning by soldiers, mitigating the risks of corrosion.9 However, this lack of chrome lining could lead to issues, particularly with corrosive ammunition or in humid environments if cleaning was neglected, a problem noted with exported rifles and the Iraqi-made Tabuk copies.9 Indeed, even rifles from various Balkan conflicts arrived in the US aftermarket with heavy bore erosion that would likely have been reduced had there been a sufficient hard chrome lining. It wasn’t until around 2020, largely driven by the demands of the commercial export market (particularly the US ZPAP series), that Zastava began consistently chrome-lining the barrels of its M70 pattern rifles.18

5. Further Specialization: Later Stamped Variants

As military tactics and technology evolved, Zastava continued to adapt the robust M70 stamped receiver platform to meet new requirements, leading to several specialized variants:

Building upon the M70B1 and M70AB2, versions were developed with factory-installed side rails to facilitate the mounting of optical sights and night vision devices:

- M70B1N: This variant combined the stamped 1.5mm bulged receiver and fixed stock of the M70B1 with an added scope rail on the left receiver wall.7

- M70AB2N: Similarly, this model added the optics rail to the underfolding stock M70AB2 platform.7

Another line of development focused on integrating dedicated underbarrel grenade launchers (UBGLs), offering potentially greater range, accuracy, and variety of munitions compared to standard rifle grenades. For these models, the original flip-up rifle grenade sight and gas cut-off were typically removed, replaced by a 40mm UBGL, likely the Yugoslav BGP 40 mm:

- M70B3: This model featured the stamped receiver and fixed stock, but was configured for use with an underbarrel grenade launcher, omitting the standard rifle grenade sight.7

- M70AB3: The underfolding stock equivalent, this variant also removed the rifle grenade sight assembly to accommodate the UBGL.7

The emergence of these ‘N’ (optics-ready) and ‘3’ (UBGL-equipped) variants demonstrates the M70’s inherent adaptability. Zastava successfully modernized the core design to incorporate technologies and meet tactical demands that evolved beyond the original concept focused heavily on integrated rifle grenade capability. This allowed the M70 platform to remain relevant and effective, extending its service life and operational utility by providing specialized tools for enhanced sighting and auxiliary firepower integration.

6. The Extended Family: Related Zastava Designs

The success and robustness of the M70 design led to its use as a foundation for other important firearms within the Zastava portfolio, creating a true family of related weapons:

- M72 RPK: Serving as the squad automatic weapon counterpart to the M70 rifle, the Zastava M72 Light Machine Gun shares the same 7.62x39mm caliber and operating principles. Crucially, it utilizes the same heavy-duty 1.5mm stamped receiver with the bulged RPK-style front trunnion found on the later M70 rifles.7 Key differences include a longer, heavier barrel (often featuring cooling fins to aid heat dissipation during sustained fire), a standard integral bipod, and sometimes modified rear sights.8 The shared receiver construction underscores the inherent strength Zastava built into their AK platform.

- M92 Carbine: For roles requiring a more compact weapon, such as for vehicle crews, special forces, or close-quarters battle, Zastava developed the M92 carbine.7 Essentially a shortened version of the M70AB2, the M92 retains the 7.62x39mm chambering, gas operation, and underfolding stock. Its most defining feature is its significantly shorter barrel, typically around 10 inches (254mm) long.8 To manage the increased muzzle blast from the short barrel, the M92 is usually fitted with a distinctive conical flash hider or muzzle booster.31 Despite the shorter barrel, the 7.62x39mm cartridge retains much of its effectiveness at typical carbine engagement ranges.31

- The Iraqi Connection: Tabuk The M70’s influence extended beyond Yugoslavia’s borders through a significant technology transfer agreement with Iraq. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Zastava provided machinery and technical assistance to Iraq’s Al-Qadissiya Establishments to set up domestic production of AK-pattern rifles.9 The resulting Iraqi rifles were collectively known as the Tabuk.

- The standard Iraqi Tabuk assault rifle was essentially a direct copy of the Zastava M70B1.7 Early production Tabuks faithfully replicated the M70B1’s features, including the 1.5mm stamped receiver with bulged trunnion, 3-slot handguards, and the integral grenade launching sight (though this was omitted on later, simplified versions).9 Critically, they also copied the non-chrome-lined barrels, which proved problematic in Iraqi service due to harsh conditions and potentially less rigorous cleaning discipline compared to the JNA.9

- Iraq also produced the Tabuk Sniper Rifle, a designated marksman rifle (DMR) based not on the M70 rifle, but on the Zastava M72 RPK.7 While visually similar to an RPK, the Tabuk DMR featured a longer, but thinner, barrel than the M72, was modified for semi-automatic fire only, included an optics rail on the receiver, and sported a distinctive skeletonized wooden buttstock with a cheek rest.24 It retained the 7.62x39mm chambering, making it effective out to intermediate ranges (around 600 meters) but lacking the reach of true sniper rifles chambered in full-power cartridges.24

- Iraqi production quality reportedly declined over time, especially after the Iran-Iraq war and subsequent sanctions.9

The development of the M72 LMG and M92 carbine, alongside the licensed production of Tabuk rifles in Iraq, highlights the M70’s significance as more than just Yugoslavia’s standard rifle. It served as a versatile and robust foundational platform adaptable to various infantry roles and was successfully exported, demonstrating Zastava’s capabilities as an arms manufacturer and technology partner during the Cold War era. The shared heavy-duty receiver across the M70B1/AB2, M72, and Tabuk variants became a defining characteristic of this branch of the Kalashnikov family tree.

7. Zastava M70 Family Variations: A Comparative Overview

The following table summarizes the key characteristics and differences between the main variants within the Zastava M70 family, tracing their evolution from the late M64 prototype stage through the various milled and stamped receiver models, as well as related designs.

Zastava M70 Family Variations Summary

| Model Designation | Receiver Type | Trunnion | Barrel Attachment | Stock Type | Grenade Sight/Gas Cutoff | Optics Rail | Key Distinguishing Features |

| M64 (late proto) | Milled | Standard | Threaded | Fixed Wood (A) / Underfolding (B) | Yes | No | 3-slot HG, Internal BHO, Grenade sight, M59/M56 parts (handle/stock) |

| M70 | Milled | Standard | Threaded | Fixed Wood | Yes | No | First production model, 3-slot HG, Grenade sight, Dust cover lock, Smooth left receiver |

| M70A | Milled | Standard | Threaded | Underfolding Metal | Yes | No | Folding stock version of M70 |

| M70A1 | Milled | Standard | Threaded | Underfolding Metal | Yes | Yes | M70A with added optics rail |

| M70B | Milled | Standard | Pressed & Pinned | Fixed Wood | Yes | No | M70 with pressed/pinned barrel |

| M70AB | Milled | Standard | Pressed & Pinned | Underfolding Metal | Yes | No | M70A with pressed/pinned barrel |

| M70B1 | Stamped (1.5mm) | Bulged RPK-style | Pressed & Pinned | Fixed Wood | Yes | No | First stamped model, Bulged trunnion, Night sights, Rubber buttpad (often) |

| M70AB2 | Stamped (1.5mm) | Bulged RPK-style | Pressed & Pinned | Underfolding Metal | Yes | No | Folding stock version of M70B1, Bulged trunnion, Night sights |

| M70B1N | Stamped (1.5mm) | Bulged RPK-style | Pressed & Pinned | Fixed Wood | Yes | Yes | M70B1 with added optics rail |

| M70AB2N | Stamped (1.5mm) | Bulged RPK-style | Pressed & Pinned | Underfolding Metal | Yes | Yes | M70AB2 with added optics rail |

| M70B3 | Stamped (1.5mm) | Bulged RPK-style | Pressed & Pinned | Fixed Wood | Replaced by UBGL | No | M70B1 adapted for UBGL (grenade sight removed) |

| M70AB3 | Stamped (1.5mm) | Bulged RPK-style | Pressed & Pinned | Underfolding Metal | Replaced by UBGL | No | M70AB2 adapted for UBGL (grenade sight removed) |

| M72 (RPK) | Stamped (1.5mm) | Bulged RPK-style | Pressed & Pinned | Fixed Wood (RPK) | No | No | LMG version, Heavy/finned barrel, Bipod, RPK sights |

| M92 (Carbine) | Stamped (1.5mm) | Bulged RPK-style | Pressed & Pinned | Underfolding Metal | No | No | Shortened M70AB2, Muzzle booster/flash hider |

| Tabuk Rifle | Stamped (1.5mm) | Bulged RPK-style | Pressed & Pinned | Fixed Wood | Yes (early) / No (late) | No | Iraqi copy of M70B1 |

| Tabuk DMR | Stamped (1.5mm) | Bulged RPK-style | Pressed & Pinned | Fixed Skeletonized | No | Yes | Iraqi DMR based on M72, Semi-auto only, 7.62x39mm, Optics rail, Skeleton stock |

Note: Barrel lining refers to original military production; modern commercial Zastava ZPAP M70 variants imported into the US typically feature chrome-lined barrels.18 HG = Handguard.

This table provides a clear, side-by-side comparison, highlighting the evolution of receiver types, barrel attachment methods, stock configurations, and specialized features across the Zastava M70 lineage, fulfilling the need for a consolidated overview of the family’s variations.

8. In Service: The M70 in Yugoslavia and Beyond

Formally adopted in 1970, the Zastava M70 quickly became the standard infantry rifle of the Jugoslovenska Narodna Armija (JNA), gradually replacing older firearms like the Zastava M59/66, itself a Yugoslav derivative of the Soviet SKS carbine.7 For over two decades, the M70, particularly the robust stamped M70B1 and M70AB2 variants, served as the primary armament for Yugoslav soldiers.

The rifle’s most prominent and tragic service came during the brutal Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s. As the federation violently disintegrated, the vast stockpiles of JNA weaponry, including millions of M70 rifles, fell into the hands of all warring factions.6 The M70 became a ubiquitous sight on the battlefields of Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo, wielded by soldiers and paramilitaries on all sides, making it an enduring, somber symbol of those conflicts.7

Following the wars, the M70 remained in service with the armed forces of the newly independent successor states, including Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Slovenia.6 While some nations, like Croatia (which donated its stocks to Ukraine 7) and Slovenia, have largely transitioned to NATO-standard firearms, the M70 continues to serve in various capacities across the former Yugoslavia.

Beyond the Balkans, the Zastava M70 achieved significant global proliferation through both official exports and the illicit arms trade fueled by the Yugoslav Wars.10 Zastava Arms exported the rifle widely during the Cold War and after, with known users including Iraq (which also produced the Tabuk copy), Cyprus, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine (PLO and PNA), and numerous African nations such as Angola, Burkina Faso, Liberia, Libya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Yemen, and Zaire (used by Serbian mercenaries).7 M70s captured from Iraq were even used by Iran.7 Rifles from former Yugoslav stocks have surfaced in conflicts across the globe, including the War in Afghanistan (provided as US military aid to Afghan forces), the Syrian Civil War, the conflict in Mali, and most recently, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, where M70s were donated by Croatia and purchased by the UK for training Ukrainian troops.6 The rifle’s presence in European terror attacks, sourced from Balkan black markets, underscores the dangerous legacy of weapons proliferation from the Yugoslav conflict.33

The sheer scale of the M70’s production, estimated at around 4 million units 7, combined with its inherent durability and the chaos surrounding the JNA’s dissolution, ensured its widespread and lasting presence. Its appearance in conflicts decades after its introduction speaks volumes about its robust design, the vast quantities produced, and the long-lasting impact of regional instability on global arms trafficking. The rifle’s legendary toughness undoubtedly contributes to its longevity in the harsh conditions often found in these conflict zones.

9. Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of the Yugoslav AK

The Zastava M70 family stands as a significant and distinct chapter in the global story of the Kalashnikov rifle. Born from Yugoslavia’s unique geopolitical position and drive for self-reliance, it represents an independent, unlicensed development path that resulted in a firearm tailored to specific national requirements.1 Its defining characteristics – the emphasis on extreme robustness evident in the thicker 1.5mm stamped receivers and RPK-style trunnions, the integral grenade launching capability that was a design priority from the outset, the evolution of the bolt hold-open feature, the distinctive three-slot handguards, and the long-standing use of non-chrome-lined barrels in military production – set it apart from its Soviet AKM contemporaries and most other licensed variants.7

While often praised for its exceptional durability and reliability, sometimes considered superior to other AKM derivatives 1, this robustness came at the cost of increased weight.9 The M70 proved itself adaptable, evolving from early milled receiver models to the ubiquitous stamped variants, and later incorporating features like optics rails and underbarrel grenade launchers to meet modern tactical needs.7 Its foundational design spawned a successful family of weapons, including the M72 LMG and M92 carbine, and served as the basis for Iraqi Tabuk production.9

From its decades of service as the standard rifle of the JNA, through its tragic ubiquity in the Yugoslav Wars, to its continued use by successor states and proliferation across global conflict zones, the Zastava M70 has carved an undeniable legacy.6 Its enduring presence is further cemented by continued production and popularity in the civilian market, particularly in the United States with the ZPAP M70 line.13 The Zastava M70 remains a highly regarded, distinctively durable, and historically significant member of the vast Kalashnikov family, a testament to Yugoslav engineering and a tangible link to a complex period of European history.

Image Source

The main photo is of a Zastava M70-AB3 from Wikimedia. It was taken on July 1, 2011 by Соколрус

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zastava_Arms_M70-AB3.jpg

Ramadi police officer with either a Zastava M70 or an early model Tabuk wherein they retained the grenade sight, 2008. Given this photo was taken in Iraq, it is most likely to be an early model Tabuk but we’d need more detail than the photo can give, notably the markings. (obtained from Wikimedia – the author submitted it to the Arabic Wikipedia and used the author name of: هــشـام or “Hisham” in Roman script)

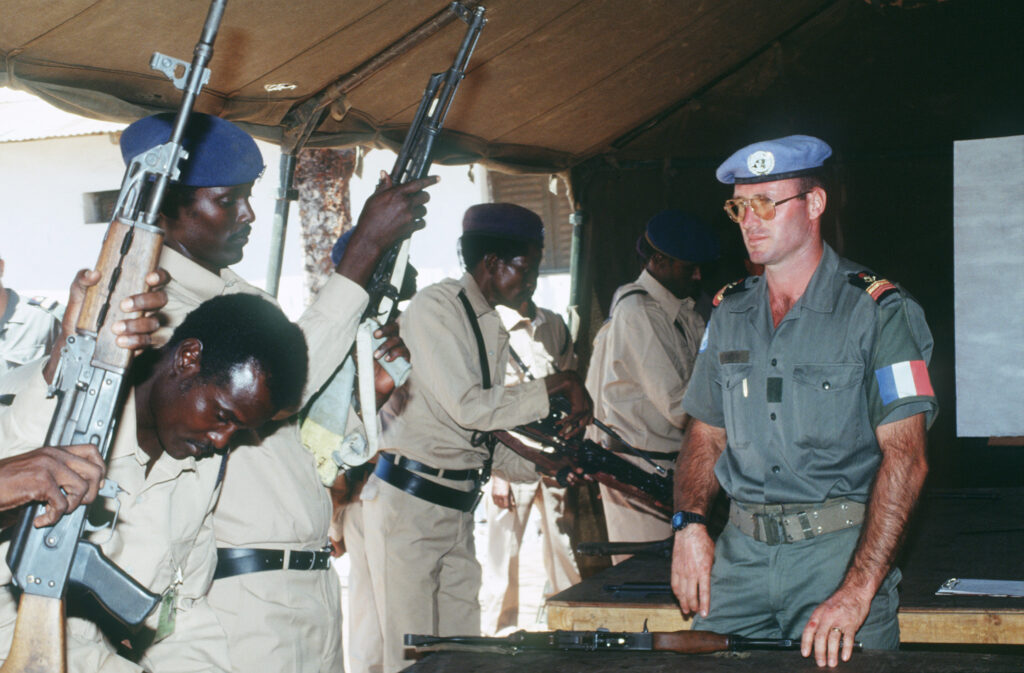

A French soldier from the Military Instruction Advisory Detachment (IMAD) of the 5th Regiment International Army Overseas (RIAOM) trains Somali policemen on the assembly and disassembly of the AK-47 assault rifle in Baidoa. The French were providing training for the Somalian police in Baidoa and Buurhakaba. (Obtained from Wikimedia and the author was Staff Sgt. Jeffrey T Brady)

Iraqi policemen from the Dhi Qar province pull security during an air assault training event with Soldiers of the 2nd Battalion, 12th Cavalry Regiment, 4th Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Regiment, at Camp Cedar, Iraq, March 2. Date: 02.25.2009. The rifle appears to be a M70AB – zooming in I can see the “URJ” Yugoslav selector markings vs. arabic script that a Tabuk would have. (Obtained from Wikimedia and the author was DVIDSHUB)

Works cited

- Zastava M64. Part 1. The Unusual History of Yugoslavian AKs …, accessed May 12, 2025, https://www.thefirearmblog.com/blog/2024/05/07/zastava-m64-part-1-unusual-history-yugoslavian-aks/

- Zastava Arms – Small Arms Defense Journal, accessed May 12, 2025, https://sadefensejournal.com/zastava-arms/

- „Заставин” музеј оружја доступан публици – Politika, accessed May 12, 2025, https://www.politika.rs/scc/clanak/368411/zastavin-muzej-oruzja-dostupan-publici

- Застава оружје — Википедија, accessed May 12, 2025, https://sr.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%97%D0%B0%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%B0_%D0%BE%D1%80%D1%83%D0%B6%D1%98%D0%B5

- Zastava M64 — Википедия, accessed May 12, 2025, https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zastava_M64

- Zastava M70 (автомат) – Википедия, accessed May 12, 2025, https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zastava_M70_(%D0%B0%D0%B2%D1%82%D0%BE%D0%BC%D0%B0%D1%82)

- Zastava M70 assault rifle – Wikipedia, accessed May 12, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zastava_M70_assault_rifle

- Guns in Movies, TV and Video Games – Zastava M70 – Internet Movie Firearms Database, accessed May 12, 2025, https://www.imfdb.org/wiki/Zastava_M70

- The History of the Iraqi AK Tabuk Rifle – Recoil Magazine, accessed May 12, 2025, https://www.recoilweb.com/the-history-of-the-iraqi-tabuk-ak-rifle-156496.html

- Zastava M70 | Weaponsystems.net, accessed May 12, 2025, https://weaponsystems.net/system/376-Zastava+M70

- M64 and M70 : r/ak47 – Reddit, accessed May 12, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/ak47/comments/162awlo/m64_and_m70/

- Yugoslavian Steel M64 “Bolt Hold Open” 30 Round AK47 Magazine – 7.62x39mm – Moka’s Raifus, accessed May 12, 2025, https://mokasraifus.com/product/yugoslavian-steel-m64-bolt-hold-open-30-round-ak47-magazine-7-62x39mm/

- Zastava ZPAP M70: An Authentic AK For The U.S. Market | An Official Journal Of The NRA, accessed May 12, 2025, https://www.americanrifleman.org/content/zastava-zpap-m70-an-authentic-ak-for-the-u-s-market/

- Zastava M70: A Yugoslav derivative of Kalashnikov rifle – Combat Operators, accessed May 12, 2025, https://combatoperators.com/firearms/rifles/zastava-m70/

- What weapons were used in the Yugoslav War? – Quora, accessed May 12, 2025, https://www.quora.com/What-weapons-were-used-in-the-Yugoslav-War

- Zastava Arms – Wikipedia, accessed May 12, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zastava_Arms

- Zastava M70 assault rifle – Wikiwand, accessed May 12, 2025, https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Zastava_M70_assault_rifle

- Zastava AKs, Part 2. M70 – The First Mass-Produced Yugoslavian Kalashnikov, accessed May 12, 2025, https://www.thefirearmblog.com/blog/2024/05/14/zastava-aks-part-2-m70-first-mass-produced-yugoslavian-kalashnikov/

- How Does The Yugoslavian Zastava M70 Compare To Other Ak-47 Variants? – GunCreed, accessed May 12, 2025, https://guncreed.com/2024/08/17/how-does-the-yugoslavian-zastava-m70-compare-to-other-ak47-variants/

- Yugo AK article – Red Star Arms, accessed May 12, 2025, http://www.redstararms.com/uploads/yugo.pdf

- YUGOSLAVIA’S AKM ZASTAVA ARMS M70 – Small Arms Review, accessed May 12, 2025, https://smallarmsreview.com/yugoslavias-akm-zastava-arms-m70/

- Yugo M70 and M72 (RPK) receivers – what’s the diff?, accessed May 12, 2025, https://forum.pafoa.org/showthread.php?t=141280

- Zastava M70 vs. AK-47: Key Differences – AR15Discounts, accessed May 12, 2025, https://ar15discounts.com/zastava-m70-vs-ak-47-key-differences/

- Tabuk Sniper Rifle – Wikipedia, accessed May 12, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tabuk_Sniper_Rifle

- Zastava USA M72 RPK Rifle 7.62 x 39 21″ Ribbed Barrel | Palmetto State Armory, accessed May 12, 2025, https://palmettostatearmory.com/zastava-usa-m72-rpk-rifle-7-62-x-39-21-ribbed-barrel.html

- Zastava 7.62×39 M72 RPK Wood Furniture Bipod 30rd Mag Semi-Auto Rifle – K-Var, accessed May 12, 2025, https://www.k-var.com/zastava-m72-rpk-rifle-762×39-wood-furniture-bipod

- Zastava M70 FAQ: Your Comprehensive Guide to a Legendary AK – AR15Discounts, accessed May 12, 2025, https://ar15discounts.com/zastava-m70-faq/

- M70 B1 Assault Rifle | Armaco JSC. Bulgaria, accessed May 12, 2025, http://www.armaco.bg/en/product/assault-rifles-c2/m70-b1-assault-rifle-p36

- ZASTAVA M70B1 semi-automatic rifle – American Liberator, accessed May 12, 2025, https://www.americanliberator.cz/en/gun/samonabijeci-puska-crvena-zastava-m70b1

- Yugo M64 RPK Rifle BFPU – Atlantic Firearms, accessed May 12, 2025, https://atlanticfirearms.com/M64-RPK-Rifle

- Zastava M92 – Wikipedia, accessed May 12, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zastava_M92

- Zastava M92 | ShootingRangePrague.com, accessed May 12, 2025, https://shootingrangeprague.com/arsenal/zastava-m92

- How Yugoslavia’s Military-Grade Weapons Haunt Western Europe – The Defense Post, accessed May 12, 2025, https://thedefensepost.com/2020/07/30/weapons-yugoslavia-europe/

- Застава М64 — Википедија, accessed May 12, 2025, https://sr.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%97%D0%B0%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%B0_%D0%9C64

- Print Page – Zastava M77 – Paluba.Info, accessed May 12, 2025, https://www.paluba.info/smf/index.php?action=printpage;topic=15504.0

- Zastava M70 (pistol) – Wikipedia, accessed May 12, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zastava_M70_(pistol)

- Застава М70 — Википедија, accessed May 12, 2025, https://sr.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%97%D0%B0%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%B0_%D0%9C70

- Застава М70 (пиштољ) — Википедија, accessed May 12, 2025, https://sr.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%97%D0%B0%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%B0_%D0%9C70_(%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%88%D1%82%D0%BE%D1%99)

- M70 AB1 Parts Kits | Zastava Arms USA, accessed May 12, 2025, https://zastavaarmsusa.com/m70-ab1-parts-kits/

- Home – Zastava oružje ad, accessed May 12, 2025, https://www.zastava-arms.rs/en/

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.