1. Executive Summary

The reporting period ending January 24, 2026, marks a definitive and volatile inflection point in the geopolitical history of the Arctic. What commenced as a resurgence of U.S. executive interest in the acquisition of Greenland—a semi-autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark—rapidly metastasized into a Tier-1 transatlantic security crisis, challenging the fundamental cohesion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and bringing the alliance to the precipice of an internal trade war.

Throughout the week, the security architecture of the High North was tested by a convergence of coercive diplomacy, economic statecraft, and asymmetric military mobilization. The crisis was precipitated by President Donald Trump’s intensified demands for “total access” and effective sovereignty over Greenland, predicated on the strategic necessities of the “Golden Dome” missile defense initiative and the securing of critical rare earth mineral supply chains.1 This demand was coupled with an unprecedented ultimatum: the imposition of punitive tariffs on eight European allies—Denmark, the United Kingdom, Norway, Sweden, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Finland—contingent upon their acquiescence to U.S. territorial ambitions.1

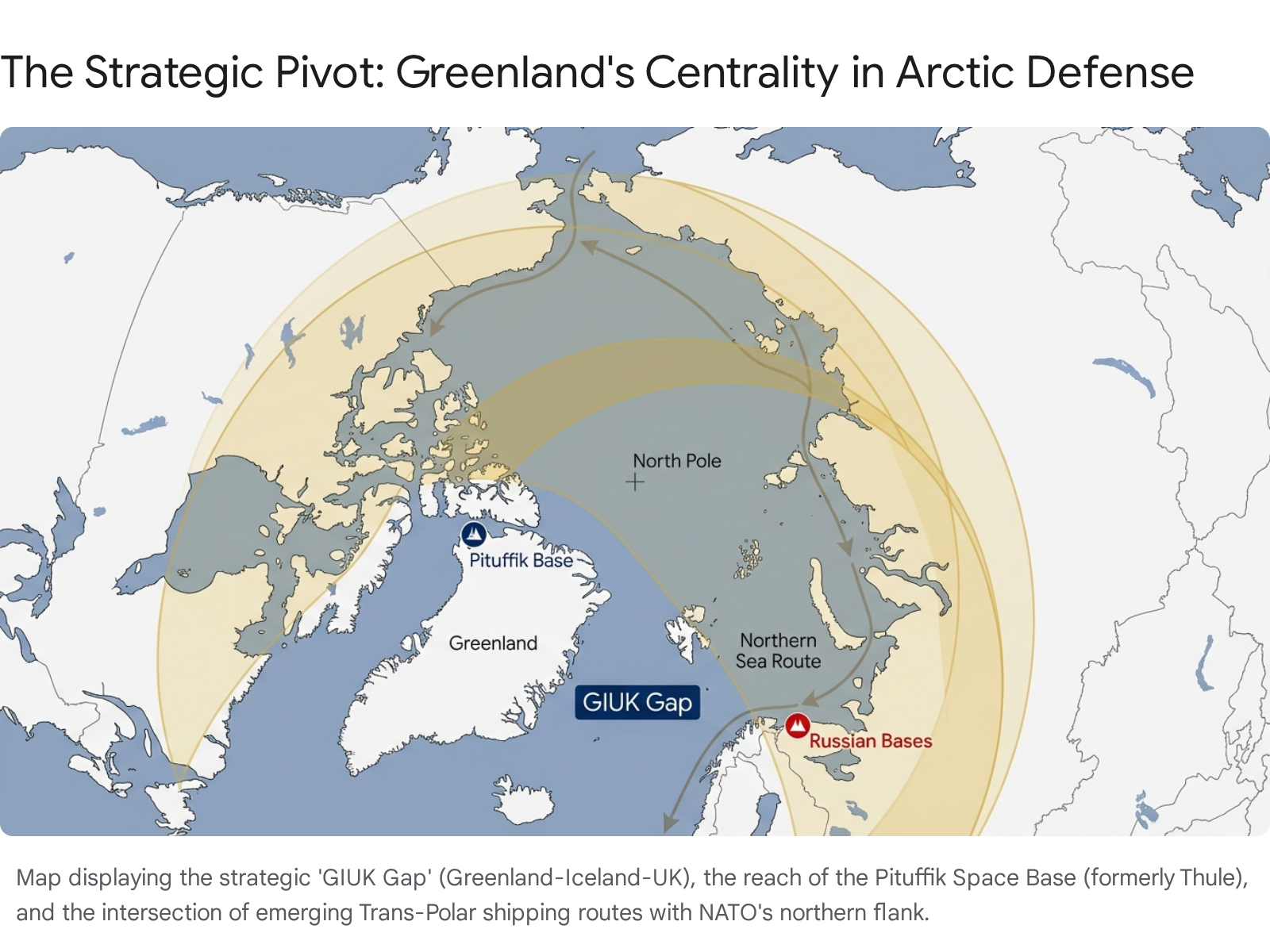

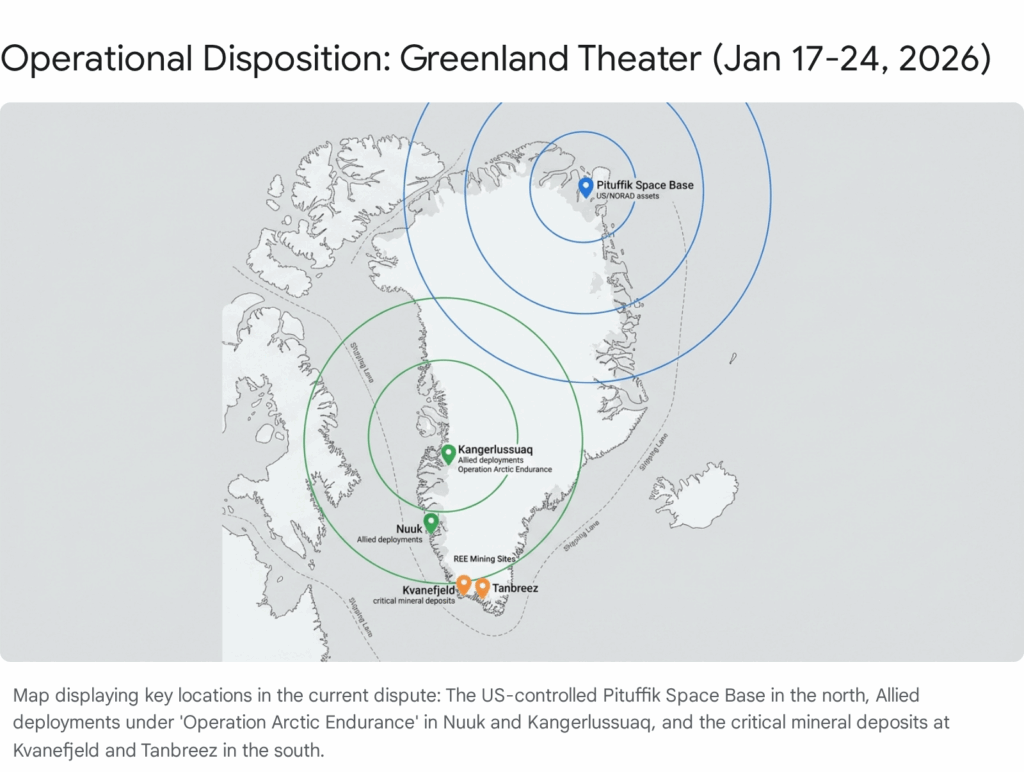

In a historic display of European solidarity, the targeted nations executed “Operation Arctic Endurance,” a multinational military deployment to Greenland designed to reinforce Danish sovereignty through physical presence.4 This maneuver created a physical “tripwire” in Nuuk and Kangerlussuaq, effectively raising the geopolitical cost of any unilateral U.S. action. The juxtaposition of U.S. North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) assets surging to Pituffik Space Base alongside European mountain infantry deploying to civilian airfields created a highly congested and high-stakes operating environment.6

The trajectory of the crisis shifted significantly on January 21 at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. Following high-level bilateral talks between President Trump and NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte, the United States announced a “framework of a future deal”.8 This tentative agreement forestalled the immediate application of tariffs and retracted explicit threats of military annexation. However, intelligence analysis indicates that this diplomatic off-ramp is fragile. The “Framework” is characterized by strategic ambiguity: while Washington claims it secures “total access” with “no end, no time limit” for military and resource exploitation, officials in Nuuk and Copenhagen maintain that sovereignty remains non-negotiable and that no such sweeping concessions have been formalized.10

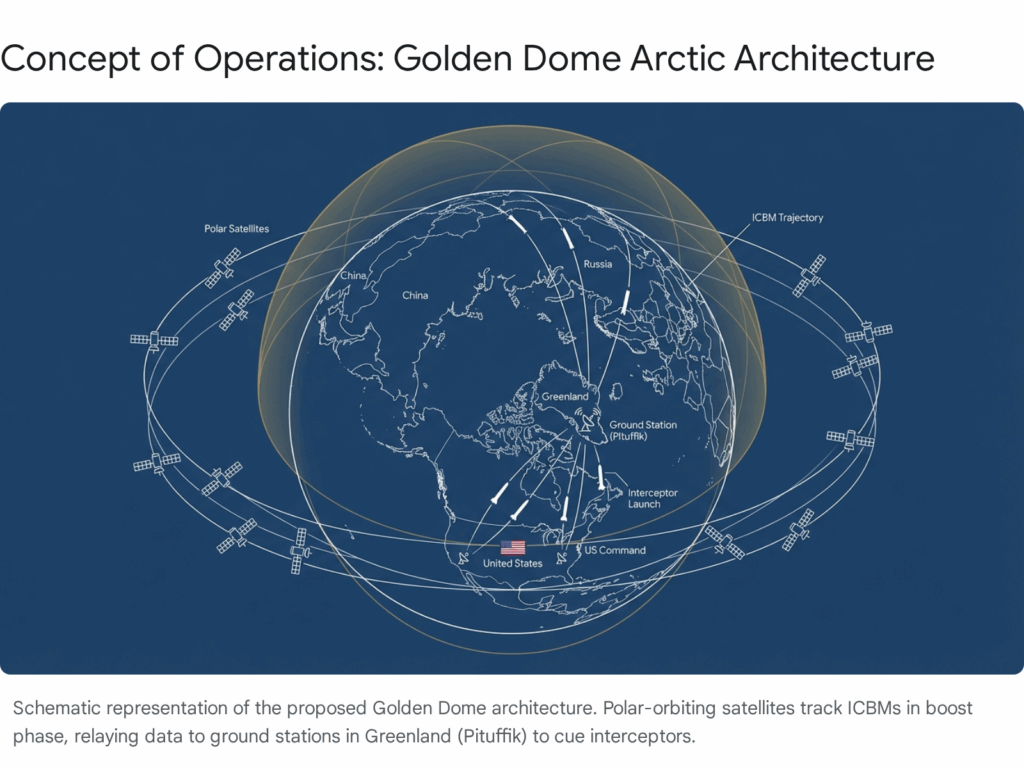

This report assesses that the “Greenland Crisis” has evolved from an acute diplomatic rupture into a complex, protracted negotiation phase. The drivers of the conflict—the U.S. requirement for a polar-based boost-phase intercept capability (“Golden Dome”), the imperative to break Chinese dominance in the critical minerals sector, and the assertion of “Make America Great Again” foreign policy—remain structural and unresolved. Simultaneously, adversaries including the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) are exploiting the intra-alliance fracture to advance their own Arctic narratives and operational footprints.12

2. Strategic Context & Historical Precedent

To understand the volatility of the week ending January 24, 2026, one must situate the current crisis within the broader arc of U.S. Arctic strategy and the historical anomalies of the U.S.-Denmark relationship. The current administration’s actions are not merely impulsive but reflect a radicalized interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine, extended to the High North—a “Donroe Doctrine” or “Arctic Monroe Doctrine”—which posits that North American security requires the exclusion of external great power influence from the Greenlandic landmass.14

2.1 The Legacy of 1941 and 1951

The United States has long viewed Greenland as an essential component of its continental defense. The Defense of Greenland Agreement of 1941 and the subsequent 1951 Defense Treaty established the legal basis for the U.S. military presence. Under these agreements, the U.S. enjoys “defense areas” within Greenland, most notably at Pituffik Space Base (formerly Thule Air Base). Crucially, the 1951 treaty grants the U.S. broad rights to “improve and generally to fit the area for military use,” a clause the current administration is leveraging to justify unilateral expansion for the “Golden Dome” without explicit new consent.15 However, Article 5 of the NATO treaty complicates this bilateral dynamic. An attack or coercive military action by the U.S. against Danish territory would theoretically trigger the collective defense mechanisms of the very alliance the U.S. leads, creating a “deep crisis” and an existential paradox for NATO.13

2.2 The Shift from Purchase to Annexation

While the “purchase” of Greenland was first floated in the 19th century (1867) and again in 1946 and 2019, the 2026 iteration of this policy represents a qualitative shift from transactional diplomacy to coercive annexation rhetoric. In 2019, the rejection of the purchase offer led to a diplomatic cancellation of a state visit. In January 2026, the rhetoric escalated to threats of “doing it the hard way” if a deal could not be reached “the easy way”.1 The administration has reframed the acquisition not as a real estate transaction but as a non-negotiable national security imperative, citing the “Golden Dome” missile shield and the threat of Chinese encroachment as justifications that override Danish sovereignty.1 This shift allows the White House to categorize opposition not as a diplomatic difference of opinion, but as a hostile act endangering the “Safety, Security, and Survival of our Planet”.19

2.3 Indigenous Self-Determination vs. Great Power Competition

A critical, often overlooked dimension is the agency of the Greenlandic people (Kalaallit). Since the 2009 Self-Government Act, Greenland has held authority over its natural resources and judicial affairs, though Denmark retains control over foreign policy and defense.20 The U.S. demands for “total access” and “ownership” directly collide with the Greenlandic independence movement. Prime Minister Jens-Frederik Nielsen has been unequivocal: “Greenland is not for sale” and “you can’t buy another people”.22 The crisis has unified Greenlandic progressives and nationalists, who interpret the U.S. move as a neo-colonial threat, replacing “hidden colonization” by Denmark with overt domination by Washington.21

3. The Crisis Escalation Phase (January 17 – January 21)

The reporting period opened with an unprecedented escalation of tensions, characterized by the weaponization of trade policy against allied nations and a responding military mobilization by European powers.

3.1 The Tariff Ultimatum: Economic Statecraft as Coercion

On January 17, President Trump formalized a threat that fundamentally altered the transatlantic relationship. Via his “Truth Social” platform, the President announced he would apply a 10% tariff on all imports from eight specific nations: Denmark, the United Kingdom, Norway, Sweden, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Finland.1

- Escalation Mechanism: The tariffs were scheduled to take effect on February 1, 2026, with a pre-programmed escalation to a 25% rate on June 1 if the “Complete and Total purchase of Greenland” was not realized.23

- Targeting Logic: The selection of these eight nations was not random. It correlated directly with the participants of “Operation Arctic Endurance,” a military exercise the White House interpreted as a direct challenge to U.S. strategic objectives. The administration labeled the participation of these nations as a “dangerous game” that put “a level of risk in play that is not tenable”.1

- The “Mister Tariff” Persona: The President reinforced this coercion by adopting the moniker “Mister Tariff” and “The Tariff King,” signaling a willingness to leverage the entirety of the U.S. consumer market to achieve territorial goals.3 This move bypassed traditional diplomatic channels, creating immediate volatility in global markets and forcing European capitals into emergency sessions.24

3.2 Operation Arctic Endurance: The European “Tripwire”

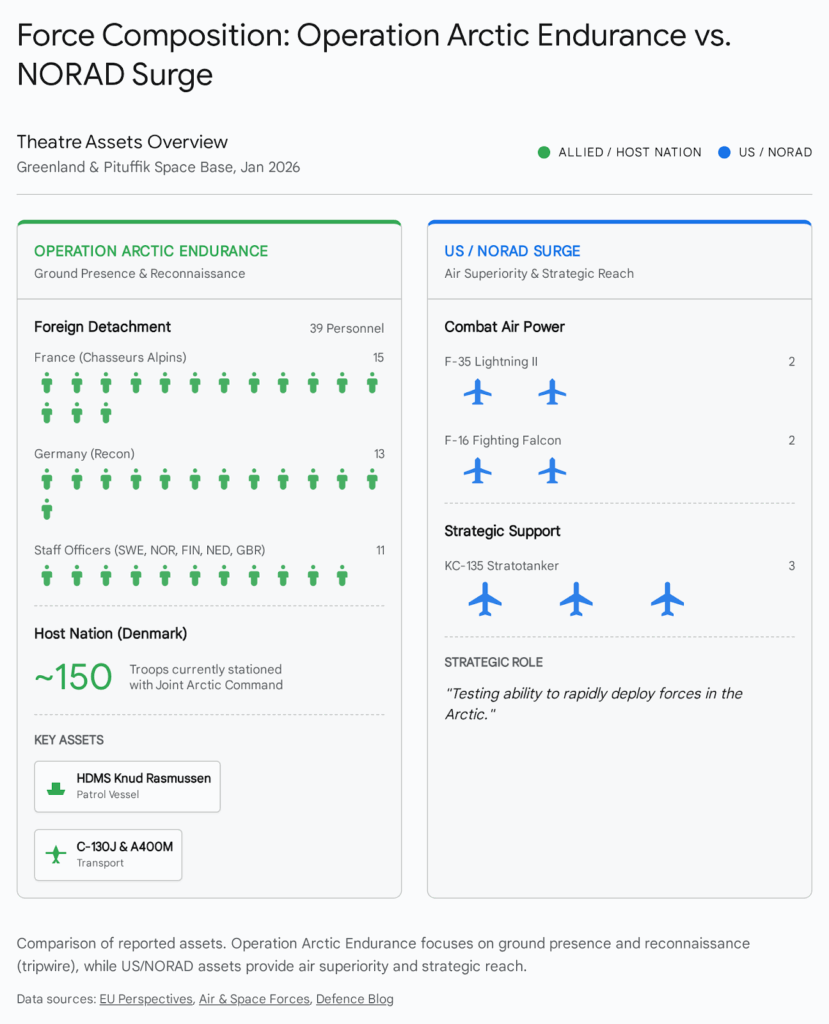

In response to the growing pressure on Denmark, a coalition of European allies initiated “Operation Arctic Endurance.” While officially characterized by participants as a routine reconnaissance and training mission to “strengthen Arctic security,” intelligence assessment confirms its primary function was strategic signaling.4

- Force Composition: The operation involved a multinational contingent deploying to Danish military facilities in Greenland. The force structure was largely symbolic yet politically potent:

- France: Deployed 15 Chasseurs Alpins (elite mountain infantry) aimed at demonstrating high-mobility Arctic capability.5

- Germany: Dispatched 13 reconnaissance specialists aboard an Airbus A400M, providing logistical and sensor support.5

- Sweden: Contributed three officers to the command element.5

- Norway & Finland: Each deployed two military personnel, leveraging their deep expertise in Arctic warfare.5

- United Kingdom & Netherlands: Each contributed a single security/liaison officer, ensuring their flags were physically present on the ground.5

- Denmark: The host nation reinforced its Joint Arctic Command with approximately 150 additional troops and the air defense frigate HDMS Peter Willemoes.5

- Strategic Intent: The deployment of fewer than 200 total personnel was militarily insufficient to repel a resolute U.S. intervention. However, it functioned effectively as a “tripwire.” Any U.S. military move to seize airfields or ports would necessitate confronting not just Danish personnel, but troops from the UK, France, and Germany, thereby invoking a wider diplomatic crisis that the White House could not easily contain.4 The operation signaled that the defense of Greenland was not merely a Danish concern, but a pan-European imperative.25

3.3 U.S. Military Surge: The NORAD Dimension

Parallel to the diplomatic standoff, the U.S. Department of Defense executed a surge of airpower to the region.

- Deployment Assets: The North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) confirmed the deployment of multiple aircraft, including F-35 Lightning II stealth fighters, F-16 Fighting Falcons, and KC-135 Stratotankers, to Pituffik Space Base.7

- Messaging Strategy: Unlike the White House’s bellicose rhetoric, military officials carefully framed these movements as “routine,” “long-planned,” and fully “coordinated with the Kingdom of Denmark”.6 This dissonance between the political and military channels suggests an attempt by the Pentagon to maintain professional military-to-military relations and the integrity of the 1951 defense treaty, even as the executive branch threatened to upend it.

- Infrastructure Investment: Coinciding with the deployment, the U.S. Air Force released solicitations for $25 million in infrastructure upgrades at Pituffik, including runway lighting and bridge repairs.28 This signals a long-term intent to sustain higher operational tempos independent of the immediate political crisis.

4. The “Golden Dome” Initiative: Strategic Driver

A central, if not the primary, driver of the U.S. administration’s pursuit of Greenland is the “Golden Dome” missile defense initiative. This project has shifted from a theoretical concept to a primary national security objective, with Greenland identified as geographically indispensable to its architecture. The administration’s rhetoric links the acquisition of the island directly to the viability of this system.

4.1 Technical Architecture and Greenland’s Vitality

The “Golden Dome” is conceptualized as a multi-layer missile defense system intended to provide comprehensive protection for the Continental United States (CONUS) against ballistic, hypersonic, and cruise missile threats.29

- Boost-Phase Intercept: Unlike current mid-course defense systems (GMD) which target warheads in space, the Golden Dome prioritizes “boost-phase” intercept—neutralizing missiles while their engines are still burning and they are most vulnerable. This requires sensors and interceptors to be positioned as close to the threat launch vectors as possible.31

- Geographic Determinism: For intercepts of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) launched from Russia or China toward North America, the flight paths traverse the Arctic pole. Greenland sits directly beneath these trajectories, offering the optimal “high ground” for ground-based interceptors to engage targets early in their flight.32

- Space-Based Relay: The system relies on a proliferated constellation of low-orbit satellites. These satellites, operating in polar orbits, face high atmospheric drag and require frequent, secure data downlinks. Ground stations in northern Greenland (specifically Pituffik) are critical for maintaining custody of tracks and relaying fire-control quality data to interceptors.31 The European Space Agency’s (ESA) construction of a rival optical ground station in Greenland has further accelerated U.S. urgency to secure its own dedicated infrastructure.31

4.2 Economic and Political Dimensions

The “Golden Dome” is not merely a defense project but a massive economic undertaking.

- Cost Estimates: President Trump has cited a cost of approximately $175 billion for the system. However, independent estimates from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) suggest the cost for space-based interceptors alone could range between $161 billion and $542 billion over two decades.35

- The “Total Access” Doctrine: The administration argues that leasing bases is insufficient justification for such a massive capital outlay. “Ownership” or “Total Access” is viewed as a prerequisite to prevent a future Danish government from evicting U.S. forces or leveraging the base for political concessions once the expensive infrastructure is installed.35 President Trump stated, “We have to have it,” arguing that without U.S. ownership, the “brilliant, but highly complex system” cannot operate at maximum efficiency due to “angles, metes, and bounds”.1

- Canadian Integration: Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent revealed that Canada has been “invited” to participate in the Golden Dome, provided they “pay their share.” This suggests a vision of a unified North American defense shield where Arctic sovereignty is pooled under U.S. operational control.35

5. The Davos Inflection (January 21)

The inflection point of the crisis occurred on January 21 at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. The interactions in Davos marked a shift from unilateral coercion to a tentative, albeit ambiguous, multilateral framework.

5.1 The Trump-Rutte Summit

President Trump held a bilateral meeting with NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte. This meeting was pivotal in de-escalating the immediate threat of trade war.

- The Outcome: Emerging from the meeting, President Trump announced via Truth Social that he and Rutte had formed the “framework of a future deal with respect to Greenland and, in fact, the entire Arctic Region.” Based on this understanding, the President announced he would not be imposing the tariffs scheduled for February 1.8

- Rutte’s Role: Analysts have described Rutte’s approach as pragmatic, potentially bordering on “sycophancy,” to placate the U.S. President and preserve alliance unity. Rutte confirmed that NATO would “ramp up security in the Arctic” as part of the deal, effectively multilateralizing the U.S. demand for a stronger military footprint.8

5.2 The “Framework” Ambiguity

The “Framework” is defined by a dangerous disconnect in interpretation between the parties involved.

- The U.S. Interpretation: President Trump claimed the deal provides the U.S. with “total access” with “no end, no time limit” to Greenland. He explicitly linked this to the “Golden Dome,” stating that “additional discussions are being held concerning The Golden Dome as it pertains to Greenland”.8

- The Danish/Greenlandic Interpretation: Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen and Greenlandic Prime Minister Jens-Frederik Nielsen have publicly welcomed the de-escalation but fiercely contested the U.S. interpretation of the deal. Nielsen stated, “I don’t know what there is in the agreement… nobody other than Greenland and the Kingdom of Denmark have the mandate to make deals.” He reiterated that “sovereignty is non-negotiable” and that while dialogue is welcome, “Greenland is not for sale”.10

- The NATO Component: The deal likely involves the establishment of a NATO “Arctic Sentry” mission. Modeled after the Baltic Air Policing, this would involve a rotational presence of NATO assets in Greenland to monitor the Arctic, thereby satisfying the U.S. demand for increased security without formally ceding sovereignty to Washington.40

5.3 Market Reaction

The announcement of the framework triggered an immediate relief rally in global financial markets. U.S. stocks jumped, and European indices recovered losses incurred during the week of tariff threats. The removal of the “February 1” deadline alleviated immediate fears of a transatlantic trade war, shifting the risk profile from “imminent economic shock” to “long-term geopolitical uncertainty”.37

6. Operational Analysis: Military Posture & Force Composition

While the diplomatic track has opened, the military reality on the ground in Greenland has shifted permanently. The region is no longer a low-tension zone but a theater of active military posturing.

6.1 Force Disparities

The confrontation highlighted a significant asymmetry in military capabilities. The European “Arctic Endurance” force, while politically significant, was militarily negligible compared to the U.S. surge.

- Allied “Tripwire” Forces: The European contingent, though small, represents a cross-section of NATO’s most capable Arctic operators. The 15 French Chasseurs Alpins are elite mountain warfare specialists. The German reconnaissance team brought specialized sensors aboard their A400M. The presence of Swedish, Norwegian, and Finnish officers integrates the force into the Nordic defense architecture. However, they lack heavy weapons, air defense, or sustained combat capabilities.5

- U.S. “Overmatch” Forces: The NORAD deployment of F-35s and F-16s represents air dominance. The F-35s provide stealth, sensor fusion, and ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance) capabilities that can monitor the entire island and surrounding waters. The KC-135s extend their range, allowing for loitering persistence. This force structure is designed not for peacekeeping but for air superiority and strategic deterrence.26

6.2 The “Arctic Sentry” Concept

The emerging “Arctic Sentry” mission concept is likely the compromise vehicle for the “Framework” deal.

- Operational Design: While no formal planning has started, Gen. Alexus Grynkewich, NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander Europe, indicated that SHAPE (Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe) has the expertise to stand up such a mission. It would likely involve maritime patrol aircraft (P-8 Poseidons), drone surveillance, and rotational naval visits to monitor the GIUK gap.43

- Political Utility: This mission allows European allies to say they are “defending Greenland” (from Russia/China) while the U.S. can claim it successfully forced NATO to “step up” and secure the American northern flank.15

7. Economic Warfare & Trade Implications

The week demonstrated the U.S. administration’s willingness to conflate security objectives with economic warfare, threatening to shatter the transatlantic trade order.

7.1 The Tariff Mechanics

The threat issued on January 17 was precise and punitive.

- Scope: A 10% tariff on all imports from the eight target nations, escalating to 25% on June 1.

- Target Selection: The list (UK, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, France, Germany, Netherlands, Finland) encompasses some of the U.S.’s closest trading partners and military allies. Targeting the UK (a “Five Eyes” partner) and France/Germany (the engines of the EU) signaled that no alliance loyalty offers immunity from the “America First” resource strategy.1

- Economic Impact: A 10-25% tariff would have devastated key European export sectors, including German automobiles, French luxury goods and aerospace (Airbus), and Nordic machinery. The European Union, operating as a single trade bloc, immediately convened emergency talks, with EU Council President Antonio Costa warning that tariffs would “undermine transatlantic relations” and were incompatible with existing trade agreements.24

7.2 The “Mister Tariff” Doctrine

President Trump’s adoption of the “Mister Tariff” persona indicates a broader doctrinal shift. The administration views the U.S. consumer market as a strategic asset to be leveraged for geopolitical concessions—in this case, territory and mineral rights. This approach bypasses the World Trade Organization (WTO) and traditional dispute resolution mechanisms, relying instead on raw economic leverage. The “pause” on these tariffs is conditional; the threat remains a “Sword of Damocles” hanging over the ongoing negotiations regarding the implementation of the Davos Framework.3

8. Resource Intelligence: The Battle for Critical Minerals

Beyond missile defense, the control of strategic resources is a primary structural driver of the conflict. Greenland holds some of the world’s largest undeveloped deposits of Rare Earth Elements (REEs), which are essential for the defense (missile guidance, lasers) and technology (batteries, chips) sectors. Breaking the Chinese monopoly on REE processing is a core U.S. national security objective.

8.1 Strategic Deposits: Tanbreez and Kvanefjeld

Two specific sites in Southern Greenland are of paramount interest to Washington:

- Kvanefjeld: Located near Narsaq, this is one of the world’s largest multi-element deposits, containing vast reserves of REEs and uranium. However, its development has been stalled by environmental concerns and a Greenlandic ban on uranium mining, a legislative hurdle the U.S. may seek to overturn through pressure.46

- Tanbreez: This deposit is rich in Heavy Rare Earths (HREEs), which are critical for high-performance magnets used in EVs and defense systems. Crucially, the U.S. Export-Import Bank (EXIM) has already issued a letter of interest for a $120 million loan to Critical Metals Corp to develop Tanbreez. This signals direct U.S. state backing for American corporate control of Greenlandic resources.47

| Deposit | Primary Resource | Strategic Value | Status |

| Kvanefjeld | REEs + Uranium | Top 5 Global Deposit | Stalled (Uranium Ban) |

| Tanbreez | Heavy REEs (Eudialyte) | High (Non-Chinese HREE source) | US EXIM Bank Funding Proposed |

| Motzfeldt | Niobium / Tantalum | Moderate | Exploration Phase |

8.2 The Anti-China Strategy

The “Framework” deal reportedly includes provisions to explicitly block Chinese and Russian investment in Greenland’s mining sector.49

- Resource Enclosure: The U.S. strategy appears to be one of “resource enclosure,” effectively integrating Greenland’s geology into the U.S. National Technology and Industrial Base (NTIB). This effectively creates a “mineral fortress” in North America, denying adversaries access to these strategic inputs.50

- Reserve Magnitude: Greenland holds an estimated 1.5 million tonnes of REE reserves, ranking it 8th globally. While this is less than China’s 44 million tonnes, the quality (high proportion of heavy rare earths) and location (outside Chinese control) make them disproportionately valuable for Western security supply chains.47

9. Adversary Reactions and Gray Zone Activity

The intra-NATO crisis has created a permissive environment for adversary exploitation.

9.1 Russia: Wedge Strategy and Northern Fleet Security

Moscow has reacted with a mix of opportunistic Schadenfreude and strategic anxiety.

- Narrative Warfare: Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and Deputy Chairman Dmitry Medvedev have utilized the crisis to amplify narratives of Western decline and NATO disunity. Lavrov’s comment that “one NATO member is going to attack another” was designed to delegitimize the alliance’s Article 5 guarantee.13

- Strategic Threat: Privately, the Kremlin is concerned. A “Golden Dome” in Greenland and an “Arctic Sentry” mission would significantly degrade the survivability of Russia’s Northern Fleet (based in Murmansk) and its ability to project power through the GIUK gap. Increased U.S. surveillance capabilities in Greenland threaten the stealth of Russian SSBNs (ballistic missile submarines) operating in the Arctic bastion.52

9.2 China: The “Near-Arctic” Ambition

Beijing views the U.S. move as a direct threat to its “Polar Silk Road” ambitions.

- Scientific Dual-Use: The Chinese icebreaker Xue Long 2 has been active in the high latitudes. While officially conducting scientific research, Western intelligence assesses these missions gather hydrographic data (salinity, thermal layers) crucial for future submarine operations in the Arctic.54

- Diplomatic Exclusion: The “Framework” deal’s reported exclusion of China from Greenlandic mining is a major setback. China has spent years cultivating ties with Nuuk through infrastructure offers (airports) and mining investments. The U.S. assertion of a “sphere of influence” effectively shuts China out of a region it views as a global commons.12

10. Domestic Political Impact

10.1 Greenland & Denmark

The crisis has triggered a surge in nationalism and anti-American sentiment.

- Protests: “Hands Off Greenland” protests occurred in Copenhagen and Nuuk. The slogan “Nu det NUUK!” (a play on “Now that’s enough”) has become a rallying cry. Organizers like the “Uagut” association are mobilizing civil society against what they perceive as an existential threat to their self-determination.3

- Political Unity: The crisis has temporarily bridged the divide between Danish unionists and Greenlandic pro-independence factions, both of whom oppose U.S. annexation. However, this unity is fragile; pro-independence hardliners may eventually argue that full independence is the only way to avoid being a pawn in US-Denmark relations.21

10.2 United States

The issue has polarized Washington along unusual lines.

- Bipartisan Concern: A bipartisan congressional delegation visited Copenhagen to reassure allies, signaling a rift between the legislative and executive branches. Senator Chris Coons publicly questioned the immediacy of the threat, stating “Are there real pressing threats… No”.57

- Executive Resolve: Conversely, the administration is unified. Advisors like Stephen Miller and Treasury Secretary Bessent frame the issue as a test of American strength and a correction of 150 years of strategic oversight.58

11. Future Outlook & Recommendations

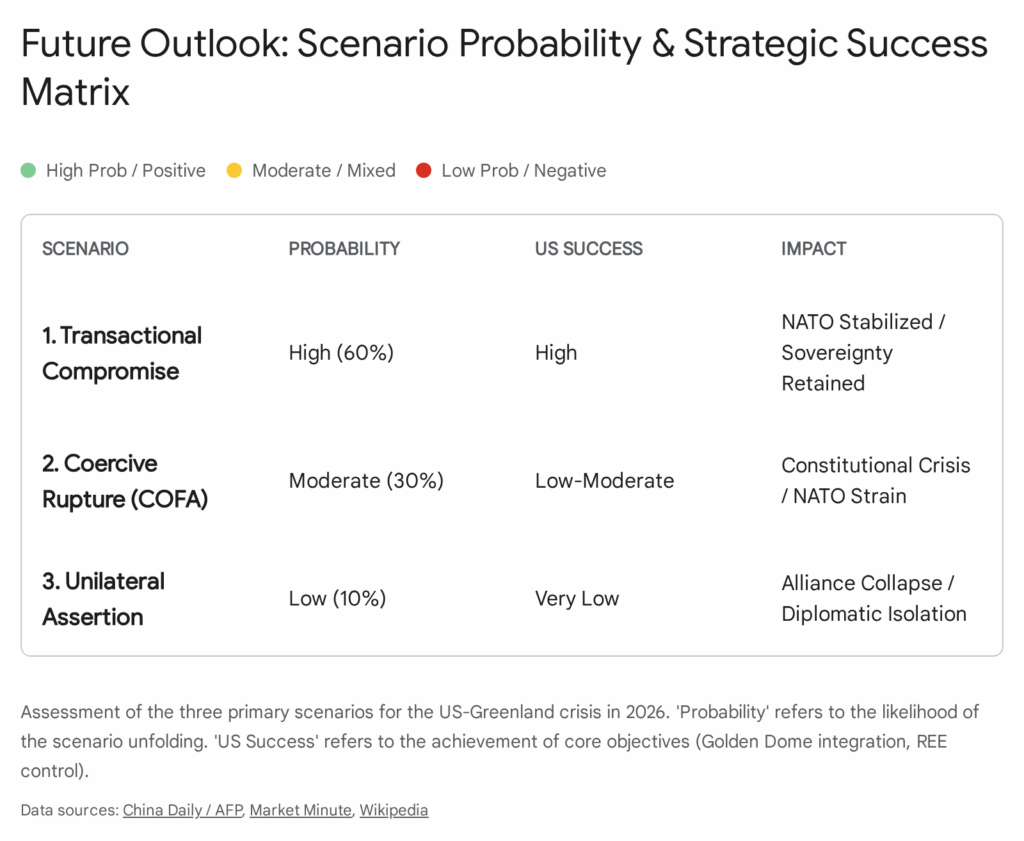

Assessment: The “Davos Framework” represents a tactical pause, not a strategic resolution. The fundamental contradiction—the U.S. demand for “total access/control” versus the Danish/Greenlandic requirement for “sovereignty”—has not been bridged.

Projected Scenarios (Next 30-90 Days):

- Bureaucratic Attrition (Most Likely): The “Framework” devolves into protracted technical negotiations. The U.S. demands specific extraterritorial rights for “Golden Dome” sites (similar to Sovereign Base Areas in Cyprus). Denmark resists. The threat of tariffs remains a lever the U.S. applies periodically to force concessions.

- Sudden Escalation: Details of the “Golden Dome” requirements leak, revealing plans for nuclear-capable interceptors or massive land seizures. Mass protests in Nuuk force the Greenlandic government to freeze talks. President Trump reacts by reinstating tariffs or ordering unilateral construction at Pituffik.

- Adversary Spoiling: Russia or China conducts a provocative maneuver (e.g., a submarine surfacing near Nuuk or a large-scale cyberattack on Danish infrastructure) to exploit the chaos and test NATO’s “Arctic Sentry” resolve.

Strategic Recommendations for Monitoring:

- Watch the Tariff Deadline: Monitor U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) notices leading up to February 1 for formal suspension or implementation of the tariff order.

- Track “Arctic Sentry” Formalization: Look for official NATO declarations regarding the mission mandate, rules of engagement, and participating assets.

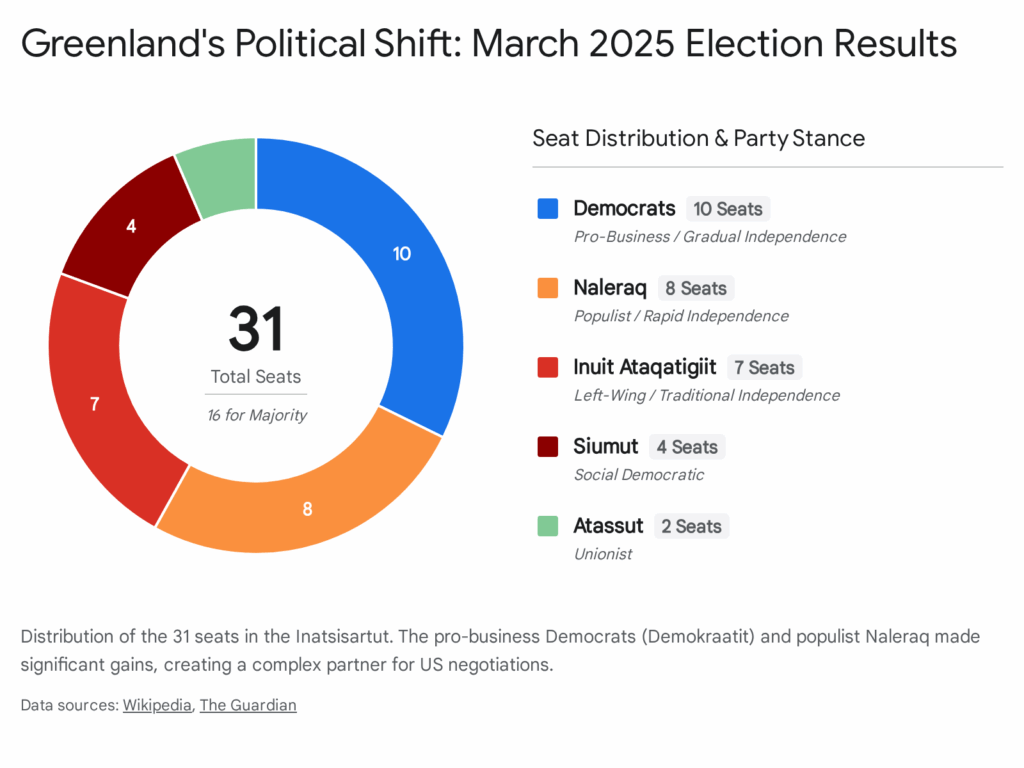

- Monitor Greenlandic Politics: Observe the Inatsisartut (Parliament) for motions of no confidence or calls for an accelerated independence referendum, which would fundamentally alter the legal landscape of the dispute.

- Surveillance of Pituffik: Monitor contract awards and construction activity at Pituffik Space Base for indicators of “Golden Dome” infrastructure groundbreaking.

END OF REPORT

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Works cited

- President Trump and Greenland: Frequently asked questions – House of Commons Library, accessed January 24, 2026, https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-10472/

- Greenland, Rare Earths, and Arctic Security – CSIS, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.csis.org/analysis/greenland-rare-earths-and-arctic-security

- European leaders warn of ‘downward spiral’ after Trump threatens tariffs over Greenland – as it happened, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/world/live/2026/jan/17/hands-off-greenland-protests-denmark-us-donald-trump-europe-latest-news-updates

- Arctic Hegemony & The Greenland Acquisition Crisis: U.S. Power Projection and the Fragmentation of Transatlantic Security – https://debuglies.com, accessed January 24, 2026, https://debuglies.com/2026/01/20/arctic-hegemony-the-greenland-acquisition-crisis-u-s-power-projection-and-the-fragmentation-of-transatlantic-security/

- Arctic Endurance demonstrates Europe’s resolve and caution – EU Perspectives, accessed January 24, 2026, https://euperspectives.eu/2026/01/arctic-endurance-demonstrates-europes-resolve/

- US sends aircraft to Greenland base amid tensions over Trump’s takeover bid, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.aninews.in/news/world/middle-east/us-sends-aircraft-to-greenland-base-amid-tensions-over-trumps-takeover-bid20260120052644

- NORAD deploys aircraft to Pituffik Space Base in Greenland – Defence Blog, accessed January 24, 2026, https://defence-blog.com/norad-deploys-aircraft-to-pituffik-space-base-in-greenland/

- Trump’s Greenland ‘framework’ deal: What we know about it, what we don’t, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2026/1/22/trumps-greenland-framework-deal-what-we-know-about-it-what-we-dont

- What’s in Trump’s “ultimate long-term deal” on Greenland?, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/trump-greenland-davos-deal-nato-rutte-whats-in-the-agreement/

- Greenland says red lines must be respected as Trump says US will …, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/22/denmark-pm-calls-for-constructive-greenland-negotiation-with-trump

- Trump declaration of Greenland framework deal met with scepticism amid tariff relief, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/22/trump-greenland-framework-future-deal-reactions

- China sees an opportunity in Greenland, but not in the way that Trump thinks – The Guardian, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/21/china-strategic-opportunity-greenland-us-donald-trump

- Russia’s Lavrov says ‘we are watching’ as NATO faces crisis over Trump and Greenland, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/russias-lavrov-says-we-are-watching-as-nato-faces-crisis-over-trump-and-greenland

- The ‘Donroe Doctrine’ reaches the Arctic – The International Institute for Strategic Studies, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.iiss.org/online-analysis/online-analysis/2026/01/the-donroe-doctrine-reaches-the-arctic/

- What’s in Trump’s Greenland ‘deal’ and will it last?, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/22/whats-in-trump-greenland-deal-and-will-it-last

- Trump’s Golden Dome excuse for Greenland grab is ‘detached from reality,’ experts say, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.defenseone.com/threats/2026/01/trumps-golden-dome-excuse-greenland-grab-detached-reality-experts-say/410693/

- Russia’s top diplomat says NATO faces a deep crisis over Greenland, accessed January 24, 2026, https://apnews.com/article/russia-lavrov-trump-putin-nato-greenland-ukraine-f4026977b1f4fb4d08be07ed54c34c07

- Why Greenland is less Golden Dome and more gold rush for rare earths | Robeco Global, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.robeco.com/en-int/insights/2026/01/why-greenland-is-less-golden-dome-and-more-gold-rush-for-rare-earths

- Operation Arctic Endurance – Wikipedia, accessed January 24, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Arctic_Endurance

- Greenland is a global model for Indigenous self-governance. Trump’s demands for the island threaten that., accessed January 24, 2026, https://grist.org/global-indigenous-affairs-desk/greenland-is-a-global-model-for-indigenous-self-governance-trumps-demands-for-the-island-threaten-that/

- Greenland’s tragedy: the dream of independence now looks like a trap laid by Donald Trump, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2026/jan/20/tragedy-greenland-independence-denmark-trump-us

- Greenland crisis – Wikipedia, accessed January 24, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greenland_crisis

- Lashing out at Europe, Trump announces ‘Greenland tariffs’, accessed January 24, 2026, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/international-business/lashing-out-at-europe-trump-announces-greenland-tariffs/articleshow/126623290.cms

- European leaders warn of ‘downward spiral’ as Trump threatens tariffs over Greenland – PBS, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/european-leaders-warn-of-downward-spiral-as-trump-threatens-tariffs-over-greenland

- Europeans trumpet Arctic defense in bid to soften US Greenland claims, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2026/01/14/europeans-trumpet-arctic-defense-in-bid-to-soften-us-greenland-claims/

- What US Military, Space Force Does in Greenland, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.airandspaceforces.com/us-military-greenland-space-force-norad/

- NORAD aircraft to arrive in Greenland for routine exercises, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.foxnews.com/politics/norad-aircraft-arrive-greenland-routine-exercises

- Five Things to Know, Jan. 19, 2026, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.legion.org/information-center/news/security/2026/january/five-things-to-know-jan-19-2026

- Golden Dome for America – Lockheed Martin, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/capabilities/missile-defense/golden-dome-missile-defense.html

- accessed January 24, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_Dome_(missile_defense_system)#:~:text=The%20Golden%20Dome%20is%20a,launch%20or%20during%20their%20flight.

- Golden Dome (missile defense system) – Wikipedia, accessed January 24, 2026, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_Dome_(missile_defense_system)

- Golden Dome and the Greenland gambit: How Trump’s Arctic obsession is rattling Russia and China, accessed January 24, 2026, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/us/golden-dome-and-the-greenland-gambit-how-trumps-arctic-obsession-is-rattling-russia-and-china/articleshow/126672082.cms

- What to know about Greenland’s role in nuclear defence and Trump’s ‘Golden Dome’, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.ctvnews.ca/world/article/what-to-know-about-greenlands-role-in-nuclear-defence-and-trumps-golden-dome/

- Does Trump’s Golden Dome Missile Defense System Really Need Greenland? – Analysis, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.eurasiareview.com/21012026-does-trumps-golden-dome-missile-defense-system-really-need-greenland-analysis/

- ‘China will eat them up’: Trump slams Canada over pushback on ‘Golden Dome’ plan in Greenland, accessed January 24, 2026, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/us/china-will-eat-them-up-trump-takes-aim-at-canada-over-golden-dome-plan-in-greenland/articleshow/127352558.cms

- What is the “Golden Dome”? Here’s what to know about Trump’s missile defense plans, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/golden-dome-for-america-trump-missile-defense-plan/

- Trump Drops Tariff Threat After Meeting Yields ‘Framework’ of Future Greenland Deal, accessed January 24, 2026, https://time.com/7355850/trump-greenland-deal-tariffs-davos/

- Trump’s Greenland U-turn was spectacular. The lesson for Europe: strongmen understand only strength, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2026/jan/23/europe-trump-climbdown-genuflecting-tacos-greenland

- Denmark and Greenland say sovereignty is not negotiable after Trump’s meeting with Rutte, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/denmark-and-greenland-say-sovereignty-is-not-negotiable-after-trumps-meeting-with-rutte

- NATO Mulls ‘Arctic Sentry’ To Ease US-Denmark Tensions Over Greenland, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.rferl.org/a/nato-arctic-sentry-greenland-us-denmark-tensions/33649807.html

- After Greenland Tensions, A Tentative Deal Comes Out Of Davos, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.rferl.org/amp/greenland-trump-nato-denmark-davos/33656891.html

- Davos Breakthrough: Trump Shelves Tariff War with ‘Framework Deal’ for Greenland NATO Integration, accessed January 24, 2026, https://markets.financialcontent.com/stocks/article/marketminute-2026-1-22-davos-breakthrough-trump-shelves-tariff-war-with-framework-deal-for-greenland-nato-integration

- Top NATO commanders standing by for policy guidance on Arctic mission, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2026/01/23/top-nato-commanders-standing-by-for-policy-guidance-on-arctic-mission/

- Joint Press Conference | NATO Transcript, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.nato.int/en/news-and-events/events/transcripts/2026/01/22/press-conference-cmc-saceur-sact

- ‘Very productive meeting’: Trump backs off on Greenland tariff threat; claims to have reached ‘framework’ for deal with European allies, accessed January 24, 2026, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/us/very-productive-meeting-trump-backs-off-on-greenland-tariff-threat-claims-to-have-reached-framework-for-deal-with-european-allies/articleshow/127047504.cms

- Wood Mackenzie finds Greenland’s rare earth sector faces multi-year development delays despite eighth-place global reserve ranking, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.woodmac.com/press-releases/wood-mackenzie-finds-greenlands-rare-earth-sector-faces-multi-year-development-delays-despite-eighth-place-global-reserve-ranking/

- Why Trump’s Greenland focus could break China’s grip on AI-critical minerals, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.foxbusiness.com/politics/why-trumps-greenland-focus-could-break-chinas-grip-ai-critical-minerals

- Critical Metals soars on project upgrades, US-Greenland talks at White House, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.northernminer.com/news/critical-metals-soars-on-project-upgrades-us-greenland-talks-at-white-house/1003886472/

- US seeks to block Russia and China from mining in Greenland – NYT, accessed January 24, 2026, https://newsukraine.rbc.ua/news/us-seeks-to-block-russia-and-china-from-mining-1769160144.html

- Greenland is not a ‘framework’, accessed January 24, 2026, https://news.cgtn.com/news/2026-01-24/Greenland-is-not-a-framework–1KbNHTWYuUo/share_amp.html

- Billionaires secretly invest in AI-driven rare earth mining in Greenland, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.engineerlive.com/content/billionaires-secretly-invest-ai-driven-rare-earth-mining-greenland

- How Russia sees opportunity and risk in Trump’s Greenland bid, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.indiatoday.in/world/story/how-russia-sees-opportunity-and-risk-in-donald-trumps-greenland-bid-2855883-2026-01-22

- With Trump-NATO deal on Greenland unclear, experts push allies to expand Arctic drone presence, accessed January 24, 2026, https://defensescoop.com/2026/01/22/trump-greenland-nato-arctic-drones/

- Russia and China build Arctic hybrid threat toolkit through shipping and “civilian” science, accessed January 24, 2026, https://euromaidanpress.com/2026/01/22/russia-china-arctic-hybrid-threats-military-civil-fusion/

- China’s icebreaker Xuelong 2 returns to Shanghai after Arctic expedition, accessed January 24, 2026, https://english.www.gov.cn/news/202509/26/content_WS68d6916ac6d00ca5f9a06790.html

- ‘We need to fight’: Trump Greenland threat brings sense of unity in Denmark, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/23/trump-greenland-threat-sense-of-unity-denmark

- In Denmark, U.S. lawmakers contradict Trump on Greenland, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2026/01/17/congressional-delegation-denmark-greenland-trump/

- As Trump menaces Greenland, this much is clear: the free world needs a new plan – and inspired leadership, accessed January 24, 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2026/jan/20/donald-trump-greenland-world-plan-leadership

- Davos 2026: Trump believes Greenland essential for US’ golden dome missile shield, says Scott Bessent, accessed January 24, 2026, https://m.economictimes.com/news/defence/greenlands-strategic-value-known-by-us-leaders-for-150-years-trump-believes-it-should-be-part-of-america-scott-bessent/articleshow/126810082.cms