The national security architecture of the United States has largely been constructed around the defense of physical borders and the projection of power abroad. For decades, the primary calculus of risk involved kinetic threats—ballistic missiles, conventional military formations, and terror cells capable of localized violence. However, a profound and largely unaddressed shift in the threat landscape has occurred, driven not by the emergence of a single new weapon, but by the structural evolution of American society itself. We have constructed a civilization reliant on services that are invisible when functioning but catastrophic when they fail. This report, prepared for the review of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence and relevant legislative committees, identifies the top ten critical infrastructure services that the American public and policymakers largely take for granted, yet which possess systemic fragilities capable of causing debilitating cascading effects across the entire national ecosystem.

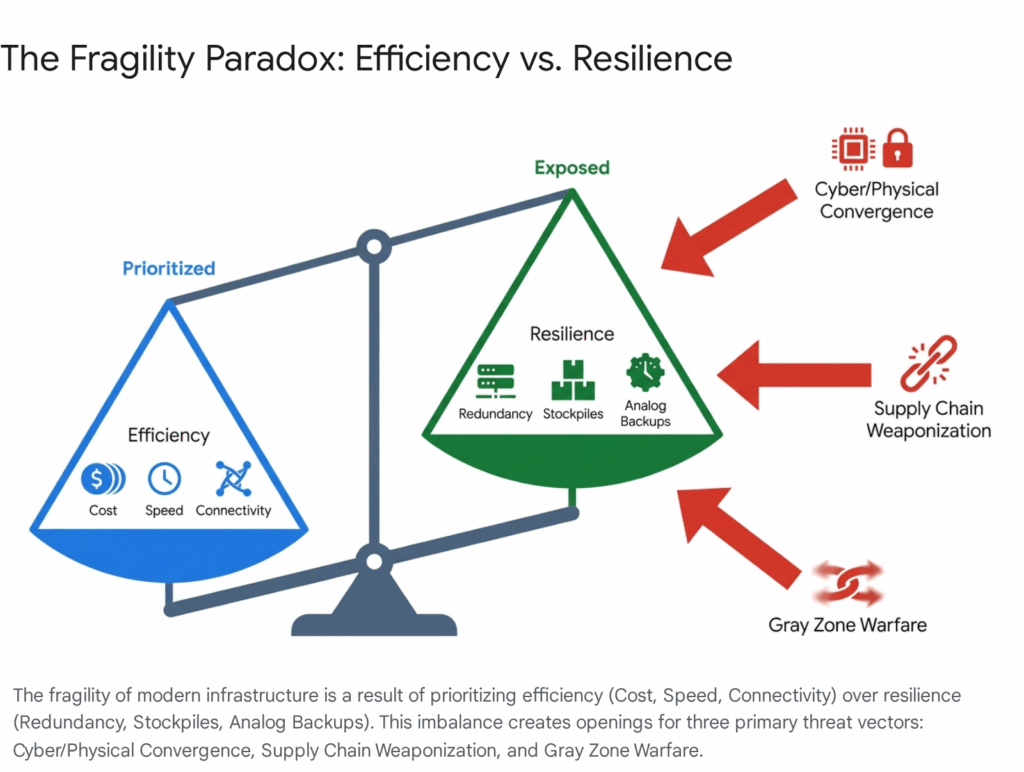

Our analysis reveals a disturbing paradox at the heart of modern infrastructure: the very mechanisms that make these services efficient—Just-in-Time (JIT) delivery, global supply chain integration, digital automation, and hyper-connectivity—are precisely what render them fragile. We have traded resilience for efficiency, creating a “glass jaw” in our national defense. The vulnerabilities identified herein are not merely theoretical; they are currently being probed by strategic adversaries, including the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Russian Federation, as well as non-state cyber actors and criminal syndicates. These actors recognize that the most effective way to degrade American power is not to engage its military, but to sever the connective tissue of its economy and society.

The ten services analyzed in this report—ranging from the timing signals of the Global Positioning System (GPS) to the active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in our medicine cabinets—share a common characteristic: high concentration risk. Whether it is a reliance on a single geographic region for manufacturing, a single protocol for internet routing, or a single mode of transport for essential goods, these single points of failure represent unacceptable risks to national security. The concept of “Critical Infrastructure” can no longer be limited to concrete and steel; it is code, chemical precursors, electromagnetic spectrum, and the delicate synchronization of financial ledgers.

The risk landscape described in this report is non-uniform. When assessing these ten services based on the severity of their potential cascading impacts and the likelihood of their disruption, a distinct clustering of high-priority threats emerges. Services such as Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) and Subsea Fiber Optic Cables occupy a quadrant of extreme concern. Here, the existential threat to national economic stability and military command and control intersects with a high probability of failure due to the documented intent of adversaries to target these specific assets. While other sectors, such as the supply of Large Power Transformers, may have a lower probability of daily disruption, their failure would result in “black sky” events—catastrophic, multi-year outages from which recovery would be geologically slow.

The analysis further indicates that the fragility of these systems is exacerbated by a lack of visibility. In many cases, such as the digital supply chain of software or the upstream origins of pharmaceutical ingredients, U.S. regulators and private sector operators lack a complete map of their own dependencies. This opacity prevents effective risk mitigation and leaves the nation vulnerable to “gray zone” warfare—coercive actions that occur below the threshold of armed conflict but achieve strategic effects through the disruption of civil society. The resilience of the United States depends not only on defending its borders but on hardening these invisible arteries of its economy against a spectrum of threats that are as diverse as they are dangerous.

Summary of Critical Infrastructure Fragilities

| Service | Primary Fragility Factor | Top Three Threats |

| 1. GPS (PNT) | Reliance on weak, space-based signals with no robust terrestrial backup. | 1. Electronic Warfare (Jamming/Spoofing) 2. Kinetic/Cyber Attacks on Space Segment 3. Severe Space Weather |

| 2. Large Power Transformers | Custom manufacturing, import reliance, and 18-48 month replacement lead times. | 1. Physical Sabotage (Rifles/Drones) 2. EMP/Geomagnetic Disturbance 3. Supply Chain Embargo |

| 3. Water SCADA | IT/OT convergence in resource-poor utilities; legacy software exposure. | 1. Chemical Manipulation Attacks 2. Ransomware 3. State-Sponsored Pre-positioning |

| 4. Subsea Cables | Geographic concentration in “choke points” and scarcity of repair ships. | 1. Maritime Hybrid Warfare (Sabotage) 2. Remote Management Hacking 3. Adversarial Control of Infrastructure |

| 5. Pharma APIs | Extreme offshore concentration (China/India) and regulatory opacity. | 1. Weaponization of Supply/Export Bans 2. Contamination/Quality Control 3. Global Logistics Collapse |

| 6. BGP & DNS | Foundation on trust-based protocols lacking inherent security validation. | 1. BGP Hijacking/Route Leaks 2. DDoS on DNS Infrastructure 3. Lack of RPKI Adoption |

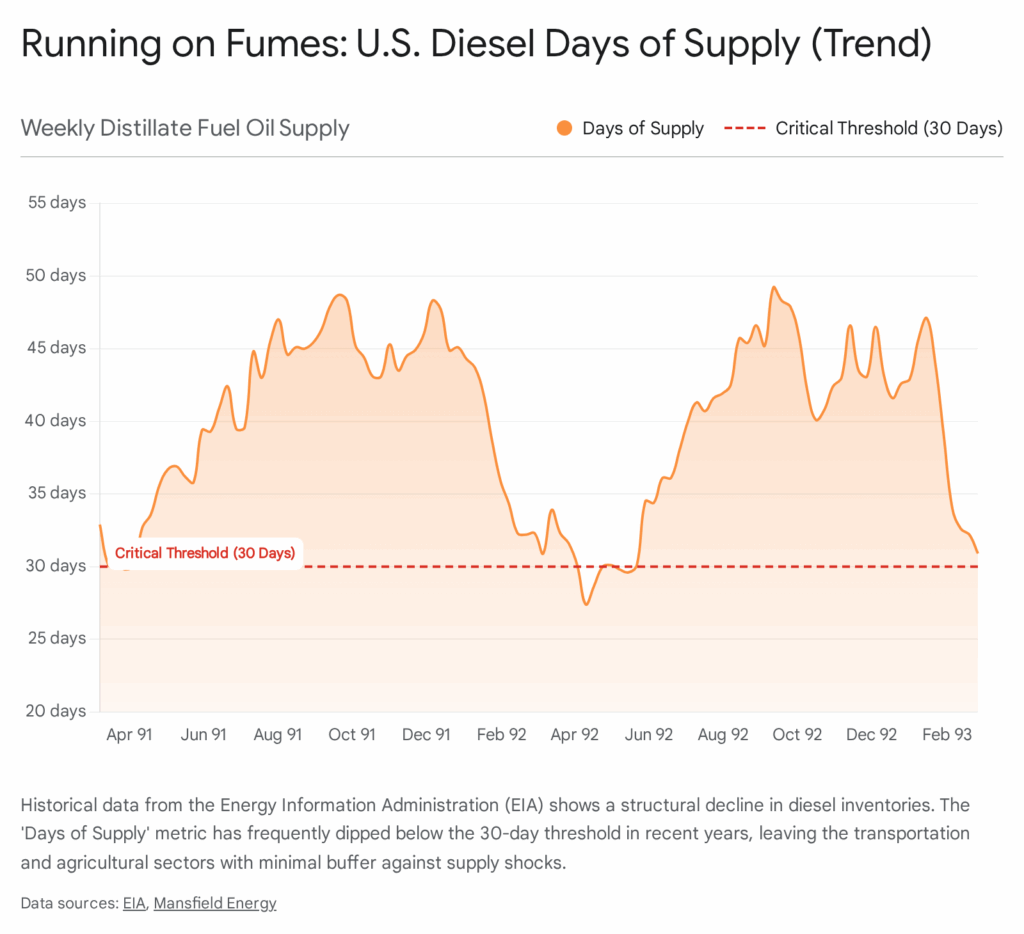

| 7. Diesel Logistics | Just-in-Time inventory (25-30 days) and reliance on pipeline choke points. | 1. Pipeline Cyberattacks 2. Refinery Capacity Loss (Weather) 3. Geopolitical Oil Shocks |

| 8. Port Cranes (ZPMC) | Monoculture of Chinese-manufactured hardware with hidden connectivity. | 1. Remote Sabotage/Port Shutdown 2. Espionage/Logistics Tracking 3. Lateral Network Movement |

| 9. Rail Signaling (PTC) | Wireless dependency and complex interoperability between carriers. | 1. Man-in-the-Middle Attacks 2. Ransomware on Control Centers 3. RF Jamming of Signals |

| 10. Wholesale Payments | Concentration of value in single nodes (FedWire/CHIPS) with no manual backup. | 1. Data Integrity Attacks 2. Operational Outages 3. Post-Quantum Decryption |

1. The Invisible Pulse: Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT)

While the public consciousness associates the Global Positioning System (GPS) primarily with the convenience of smartphone maps and automotive navigation, its role in the national infrastructure is far more profound and precarious. GPS is the world’s primary source of distinct Timing signals, a function that is arguably more critical to national security than navigation itself. The constellation of satellites, operated by the U.S. Space Force, provides a ubiquitous, free, and highly precise reference for time, synchronized to the nanosecond via onboard atomic clocks. This signal has become the silent drumbeat of the modern world, orchestrating the operations of the power grid, financial markets, and telecommunications networks. It is a service so omnipresent that it has become effectively invisible to those who rely on it, yet it represents a singular point of failure for modern civilization.

Why It Is Fragile

The fragility of the PNT architecture stems from an asymmetric vulnerability: the reliance of critical, high-stakes terrestrial systems on a weak, space-based signal that was never designed to operate in a contested electronic warfare environment. The GPS signal originates from satellites in Medium Earth Orbit (MEO), approximately 12,550 miles above the planet. By the time this signal reaches the Earth’s surface, its strength is incredibly low—often compared to the power of a 25-watt lightbulb viewed from 10,000 miles away. This extremely low signal strength makes the system exceptionally susceptible to interference. It does not require a nuclear detonation or a kinetic satellite kill vehicle to disrupt GPS; it can be drowned out (jammed) or mimicked (spoofed) by relatively inexpensive terrestrial transmitters.

Despite this inherent physical fragility, critical sectors have baked GPS dependency into their core operations, often without adequate analog backups or holdover clocks capable of maintaining synchronization during an outage. This dependency creates a mechanism for cascading failure.

Financial Synchronization and Market Integrity

The financial sector is heavily dependent on GPS timing to timestamp transactions. Under regulations such as the Consolidated Audit Trail (CAT) in the United States and MiFID II in Europe, financial institutions are required to synchronize their clocks to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) within microsecond tolerances. This precision is necessary to sequence high-frequency trades, detecting market abuse and ensuring the integrity of the ledger. A drift in timing or a spoofing attack that alters the timestamp could lead to massive trade failures, the inability to reconcile transactions, or “flash crash” scenarios where automated trading algorithms react to erroneous temporal data.1

Grid Stability and Phasor Measurement

The modern electrical grid has evolved from a simple delivery system to a complex, automated network that relies on real-time data to balance load and generation. Phasor Measurement Units (PMUs) are deployed across the grid to measure the phase angle of the alternating current (AC) at various points, ensuring that power flows remain synchronized. These PMUs utilize GPS time stamps to align their measurements across thousands of miles. If the GPS signal is lost or corrupted, grid operators lose their situational awareness of phase alignment. In a stressed grid scenario, this loss of synchronization data could prevent automated systems from isolating faults, leading to equipment damage and massive, cascading blackouts similar to the 2003 Northeast blackout, but potentially on a wider scale.

Telecommunications and 5G

Cellular networks require precise timing to manage the handoff of calls between towers and to maximize the efficiency of spectrum usage. This is particularly acute in 5G networks, which often use Time Division Duplexing (TDD). In TDD, the same frequency band is used for both uploading and downloading data, with the distinction made by assigning specific time slots for each direction. GPS timing provides the synchronization for these slots. A loss of timing accuracy leads to “inter-cell interference,” where upload and download signals collide, effectively degrading or destroying network capacity.

We have effectively built the logistical and economic engine of the nation on a foundation of weak radio waves that are easily disrupted. The lack of a robust, widely deployed terrestrial backup system (such as eLORAN) leaves the U.S. uniquely exposed compared to adversaries who have maintained or modernized their ground-based navigation infrastructure.

Top Three Threats

1. Electronic Warfare (Jamming and Spoofing)

The proliferation of electronic warfare (EW) capabilities represents the most immediate threat to PNT services. Adversaries, notably the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China, have integrated GPS jamming into their military doctrine and deployed it aggressively in “gray zone” conflicts.2 Observations from the Baltic region and the ongoing conflict in Ukraine demonstrate Russia’s capability and willingness to blanket vast areas with high-power jamming signals, disrupting civil aviation and maritime traffic. In a domestic context, the threat extends to the availability of low-cost, portable jamming devices (often called “privacy jammers”) which, while illegal, are widely available online. A coordinated attack using such devices near critical financial hubs or power substations could create localized “PNT-denied” environments. More insidious is the threat of spoofing, where an adversary transmits a counterfeit GPS signal that slowly drifts in time or position. This can deceive automated systems—such as those on autonomous vehicles or grid controllers—into making catastrophic errors before the manipulation is detected.3

2. Kinetic and Cyber Attacks on the Space Segment

The physical satellites of the GPS constellation and their ground control infrastructure are valid military targets in the eyes of potential adversaries. Anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons testing by China and Russia has confirmed their capability to physically destroy satellites in orbit, creating debris fields that could deny the use of space for generations. Perhaps more concerning is the threat to the ground control segment—the master control stations that upload orbital corrections and clock updates to the satellites. A cyber intrusion that corrupts this data could render the entire constellation inaccurate or unusable without a single physical shot being fired.2 This vector attacks the “trust” inherent in the system, turning the GPS signal from a utility into a vector for misinformation.

3. Atmospheric and Space Weather Events

Not all threats are adversarial; some are environmental and inevitable. The GPS signal must pass through the Earth’s ionosphere to reach receivers. Severe solar activity, such as a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) or a “Carrington-class” geomagnetic storm, can cause extreme turbulence in the ionosphere. This scintillation can degrade the signal, introducing massive errors or causing a complete loss of lock for receivers across the entire hemisphere facing the sun. Unlike a localized jamming attack, a space weather event would affect the entire continent simultaneously. The current hardening of civilian infrastructure against such an event is minimal, and the potential for a global timing desynchronization event remains a high-probability risk over a long enough timeline.

2. The Grid’s Heavy Heart: Large Power Transformers (LPTs)

Large Power Transformers (LPTs) are the massive, critical nodes that act as the interface between high-voltage transmission lines and the distribution grid that serves homes and businesses. They are the backbone of the electrical system, handling more than 90% of the nation’s power flow. These behemoths, often weighing between 100 and 400 tons, step down voltage from hundreds of thousands of volts to levels that can be managed by local substations. Despite their imposing physical size, LPTs are surprisingly fragile components and, most critically, represent one of the most severe supply chain bottlenecks in the U.S. national security apparatus. They are the definition of “heavy infrastructure” that cannot be easily replaced, repaired, or bypassed.

Why It Is Fragile

The fragility of the LPT fleet is defined by a dangerous combination of age, lack of standardization, and an atrophied domestic industrial base. LPTs are not off-the-shelf components; they are almost exclusively custom-engineered to meet the specific voltage, impedance, and physical constraints of the substation where they are installed. This lack of interchangeability means that a utility cannot simply pull a spare off a shelf when one fails.

The Manufacturing Void and Import Dependence

The United States has allowed its domestic capacity to manufacture these critical assets to wither. The production of LPTs requires specialized grain-oriented electrical steel (GOES) and massive winding facilities. Currently, the U.S. imports the vast majority of its LPTs and the components to build them, primarily from partners in Europe and Asia, but increasingly relying on global supply chains that are vulnerable to disruption. There are fewer than ten manufacturing facilities in the United States capable of producing LPTs, and they cannot meet domestic demand even in peacetime, let alone during a crisis recovery.4

The Lead Time Crisis

The implications of this manufacturing deficit are quantified in lead times. Prior to 2020, the procurement cycle for a new LPT was already significant, averaging 12 to 18 months. However, post-pandemic supply chain constraints, labor shortages, and raw material scarcity have caused this timeline to balloon dramatically. Current estimates suggest lead times of 18 to 48 months—up to four years—for a new unit.5 This timeline is incompatible with national resilience. If a coordinated attack or natural disaster were to destroy multiple LPTs simultaneously, the U.S. could face a “black sky” hazard—a multi-year outage affecting millions of citizens, with no physical possibility of rapid restoration.6

Logistical Nightmares

Even if a replacement unit exists, moving it is a monumental logistical challenge. Transporting an LPT requires specialized rail cars (Schnabel cars) that can support the immense weight and height of the unit. There is a limited number of these cars in existence. The journey from a port or factory to a substation often requires months of route planning, bridge reinforcement, and road closures. In a crisis scenario where infrastructure may be damaged, the physical movement of spares becomes exponentially more difficult.

Top Three Threats

1. Physical Sabotage (Rifle and Drone Attacks)

The vulnerability of LPTs to low-tech physical attack was starkly illustrated by the 2013 Metcalf sniper attack in California. In that incident, attackers used standard rifles to fire on the radiator fins of the transformers, draining thousands of gallons of cooling oil and causing the units to overheat and fail. Despite industry efforts to erect visual barriers and enhance monitoring, thousands of substations remain located in remote, unmanned areas protected only by chain-link fences. A coordinated campaign by small tactical teams or the use of commercial drones delivering explosive payloads could disable dozens of key nodes within hours, bypassing cyber defenses entirely.

2. Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP) and Geomagnetic Disturbance (GMD)

LPTs are the components most susceptible to geomagnetically induced currents (GIC). In the event of a high-altitude nuclear detonation (HEMP) or a massive solar flare, long transmission lines would act as antennas, capturing the electromagnetic energy and channeling it as direct current (DC) into the grid. This DC current would enter the transformers, causing magnetic saturation of their cores. This leads to rapid internal heating, melting the copper windings and destroying the insulation. Unlike a physical attack which might damage the exterior, a GMD event destroys the core of the machine, rendering it unrepairable. Such an event could theoretically destroy hundreds of LPTs across the continent simultaneously, exceeding the global manufacturing capacity for replacements by an order of magnitude.

3. Supply Chain Interdiction and Embargo

In the context of great power competition, the supply chain itself is a weapon. The reliance on imported electrical steel and finished units creates a strategic leverage point for adversaries. In a conflict scenario, an adversary could impose an embargo on the export of LPTs or their critical components to the United States. Furthermore, the maritime transport of these units makes them vulnerable to interdiction at sea. If the U.S. were engaged in a conflict in the Pacific, the flow of replacement transformers from Asian manufacturers would likely cease, precisely at the moment when the homeland grid might be under cyber or physical attack. The inability to resupply would transform temporary outages into permanent de-electrification of affected regions.

3. The Digital Toxin: Water and Wastewater SCADA Systems

The United States water and wastewater sector consists of approximately 153,000 public drinking water systems and 16,000 wastewater treatment systems. This vast, decentralized network is responsible for a biological necessity, yet it operates with a level of digital insecurity that is startling given the consequences of failure. These utilities rely on Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) networks to monitor flow rates, pressure, and, most critically, to automate the mixing of dangerous chemicals—such as chlorine, fluoride, and sodium hydroxide (lye)—into the water supply. We take the safety and availability of clean water for granted, but the digital infrastructure ensuring its purity is arguably the softest target in the national critical infrastructure portfolio.

Why It Is Fragile

The fragility of the water sector is structural and economic, characterized by extreme fragmentation and a lack of resources. Unlike the energy or financial sectors, which are dominated by large, well-funded conglomerates with dedicated security teams, the water sector is composed largely of small municipal authorities.

Resource Poverty and IT/OT Convergence

Many water utilities serve small populations and operate on shoestring budgets. They often lack a single dedicated cybersecurity staff member. In an effort to modernize and reduce costs, these utilities have increasingly connected their Operational Technology (OT) networks—the pumps and valves—to their Information Technology (IT) networks and the public internet to allow for remote monitoring and maintenance. This “IT/OT convergence” has occurred without the requisite security controls, effectively air-gapping the systems in reverse—connecting formerly isolated critical controls to the global threat landscape.

Exposure and Obsolescence

Security audits and internet scanning tools like Shodan frequently identify hundreds of water facility Human-Machine Interfaces (HMIs) that are directly accessible from the public internet, often protected by default passwords or no authentication at all.7 Furthermore, the long lifecycle of industrial equipment means that critical control software often runs on obsolete, unsupported operating systems like Windows 7 or even Windows XP, which are riddled with unpatched vulnerabilities.

Single Points of Failure

In many smaller and rural systems, the central SCADA master unit acts as a single point of failure. If this system is compromised or ransomed, operators lose visibility into the treatment process. Crucially, as institutional knowledge retires, many younger operators are entirely dependent on these digital systems and may lack the training or the physical staffing levels required to switch to manual operations for an extended period. The loss of the digital brain leads to a shutdown of the physical body of the plant.

Top Three Threats

1. Chemical Manipulation Attacks

The nightmare scenario for the water sector is not just the disruption of service, but the weaponization of the treatment process itself. This was demonstrated in the 2021 incident at a water treatment plant in Oldsmar, Florida, where an attacker remotely accessed the SCADA system via TeamViewer and attempted to increase the concentration of sodium hydroxide (lye) from 100 parts per million to 11,100 parts per million.8 Had this change not been noticed by an alert operator, it could have resulted in the poisoning of the local population. This incident proved that adversaries have the capability and intent to use the utility’s own automation against it, turning a public health system into a delivery mechanism for toxic agents.

2. Ransomware and Criminal Extortion

Ransomware groups have increasingly identified water utilities as lucrative targets. Attacks involving variants such as Ghost, ZuCaNo, and Makop have successfully breached water and wastewater facilities.9 While these actors are typically motivated by profit rather than destruction, the effect is often operational paralysis. A ransomware infection can lock operators out of their monitoring systems, blinding them to the status of pumps and chemical levels. In such a state of “blindness,” utilities are often forced to shut down operations entirely to ensure safety, leading to service interruptions and the potential for untreated wastewater to be discharged into the environment.

3. State-Sponsored Pre-Positioning

Intelligence assessments from CISA and the FBI have confirmed that state-sponsored actors, specifically the PRC-linked group “Volt Typhoon,” have been actively pre-positioning themselves within U.S. critical infrastructure IT networks. The water sector is a prime target for this pre-positioning because it offers high psychological impact with a low barrier to entry. By embedding themselves in these networks, adversaries gain the leverage to induce panic or distract decision-makers during a future geopolitical crisis. The goal is not immediate destruction, but the establishment of a “kill switch” that can be activated to cause societal chaos when strategically advantageous.

4. The Glass Arteries: Subsea Fiber Optic Cables

There is a pervasive misconception that the global internet is a wireless, cloud-based phenomenon supported by satellites. In reality, the “Cloud” is under the ocean. More than 95% of all international data traffic—including diplomatic cables, military logistics data, financial transfers (SWIFT), and the entirety of the consumer internet—travels through a network of roughly 600 subsea fiber optic cables.10 These cables are the physical manifestation of globalization, hair-thin strands of glass laid across the seabed that connect continents. Despite their absolute centrality to the global economy and U.S. command and control, they lie largely unprotected in international waters, subject to a legal and security regime that has not kept pace with their strategic importance.

Why It Is Fragile

The fragility of the subsea network is a function of its physical exposure, geographic concentration, and the scarcity of repair capabilities.

Choke Points and Geographic Concentration

While the ocean is vast, the routes available for cable laying are constrained by bathymetry, geopolitical boundaries, and historical precedent. This has led to the formation of extreme “choke points” where dozens of critical cables run in close proximity. The Red Sea, the Strait of Malacca, and the Strait of Luzon are prime examples. A kinetic event in these narrow corridors—whether an underwater landslide or a targeted attack—could sever multiple cables simultaneously, severing connectivity between entire regions. Similarly, cables often converge at a few key landing stations on the U.S. coast (e.g., the New York/New Jersey coastline, Ashburn’s coastal links). These landing sites are stationary, well-known targets that represent the “last mile” vulnerability of the trans-oceanic system.

Repair Scarcity

The global fleet of cable repair ships is surprisingly small, aging, and oversubscribed. There are fewer than 60 such vessels in the world capable of grappling and splicing cables at depth. In peacetime, a cable break might take weeks to repair depending on ship availability and weather. In a conflict scenario involving widespread sabotage, the demand for repairs would instantly overwhelm the global capacity. The U.S. reliance on foreign-flagged vessels for much of this maintenance adds another layer of dependency.

Opacity and Private Ownership

Historically, cables were owned by consortiums of national telecom operators. Today, the landscape is dominated by private technology giants (Google, Meta, Microsoft, Amazon), who view the routes and technical specifications as proprietary commercial data. This shift creates challenges for government defense planning, as the “map” of critical infrastructure is privately held and constantly changing, obscuring the true resilience—or lack thereof—of the network.

Top Three Threats

1. Maritime Hybrid Warfare (The “Gray Zone”)

The Russian Federation has invested heavily in specialized naval assets, such as the Yantar-class oceanographic research vessels and the GUGI (Main Directorate of Deep-Sea Research) fleet. These vessels are equipped with submersibles capable of descending to great depths to cut or tap cables. The threat doctrine is one of “plausible deniability.” Recent incidents in the Baltic Sea and the Arctic, where cables were severed by “accidental” anchor drags from Russian-linked commercial vessels, serve as a proof of concept.11 In a crisis, an adversary could sever key transatlantic or transpacific links, degrading U.S. communications with NATO allies or Asian partners, while claiming the damage was an unfortunate maritime accident.

2. Remote Management System Hacking

Modern subsea cables are not just passive glass tubes; they are active systems equipped with repeaters and power feeds that are managed by onshore Network Management Systems (NMS). As cable operators seek efficiency, these management systems have become increasingly accessible via the internet to allow for remote administration. This introduces a cyber threat vector. Hackers could theoretically compromise an NMS to shut down the power feeding the repeaters, effectively “turning off” the cable without ever touching the ocean floor. Alternatively, they could manipulate the data flow or blind the operators to physical tampering occurring at sea.12

3. Great Power Competition for Control (The “Digital Iron Curtain”)

The PRC is actively competing to build the physical layer of the internet. Chinese state-owned enterprises like HMN Tech (formerly Huawei Marine) have become major players in the cable laying market, often undercutting Western competitors to win contracts in the Global South and Europe. This creates the risk of a bifurcated internet infrastructure. If critical data traffic is routed through cables owned, maintained, or landed by adversarial powers, it is subject to espionage, data siphoning, or potentially “kill switch” capabilities. The U.S. fears that cables built by PRC entities could function as intelligence collection platforms, embedding surveillance deep into the architecture of the global web.

5. The Chemical Choke Point: Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs)

The U.S. healthcare system operates on the assumption that life-saving medicines will always be available on pharmacy shelves and in hospital emergency rooms. However, the domestic production of the raw materials for these drugs—Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs)—has all but vanished from American soil. The United States has outsourced its biological resilience to foreign nations, primarily China and India (the latter of which relies heavily on China for chemical precursors). This has created a national security vulnerability where the health of the American population is dependent on supply chains that are opaque, fragile, and subject to geopolitical leverage.

Why It Is Fragile

The fragility of the pharmaceutical supply chain is structural and economic, driven by decades of market forces that prioritized low cost over security of supply. The production of APIs is chemically intensive, often polluting, and has lower profit margins than the development of new branded drugs. Consequently, Western pharmaceutical companies offshored this production to Asia.

Dependency Statistics

Current FDA data and independent analyses suggest that approximately 72% of API manufacturing facilities supplying the U.S. market are located overseas.13 The concentration is even higher for specific essential medicines. For critical generic drugs—including antibiotics (like penicillin and cephalosporins), sedatives used in surgery, and chemotherapy agents—reliance on Chinese sources for APIs or Key Starting Materials (KSMs) is estimated to be near 90%.14 This is a “single point of failure” on a continental scale.

Opacity and the “Blind Spot”

A major contributor to this fragility is the lack of visibility. Drug manufacturers are not required to list the country of origin for APIs on consumer packaging. More concerning, the FDA struggles to effectively inspect facilities in China due to visa restrictions, lack of cooperation from Chinese authorities, and the sheer number of producers. This creates a regulatory blind spot. We do not know the true quality or resilience of the factories making our medicines.

Inability to Pivot

Unlike other manufacturing sectors where production might be shifted to a new factory in months, pharmaceutical manufacturing is rigidly regulated. Qualifying a new API supplier requires rigorous FDA validation, stability testing, and process verification, a process that can take 18 months to several years. There is no “surge capacity” in the U.S. to replace lost imports. If the supply from China were cut off, the U.S. would face immediate and unmitigated shortages.

Top Three Threats

1. Weaponization of Supply

In a geopolitical conflict, such as a confrontation over Taiwan or a severe trade dispute, Beijing possesses the leverage to restrict the export of critical APIs to the United States. This would not require a naval blockade; it could be achieved through administrative delays, export quotas, or “safety inspections” at Chinese ports. Such an action would be a form of biological warfare conducted through bureaucracy. Within weeks, U.S. hospitals would face shortages of antibiotics to treat sepsis, sedatives for intubation, and drugs for managing chronic conditions, creating a public health crisis that would erode political will and societal stability.15

2. Quality Control and Contamination

The reliance on opaque foreign manufacturers increases the risk of contaminated or ineffective drugs entering the U.S. supply chain. This threat can manifest through negligence (cutting corners to save money) or malicious intent. The 2008 heparin scandal, where contaminated ingredients from China led to deaths in the U.S., illustrates the danger. In a period of tension, an adversary could introduce subtle defects into the drug supply—lowering potency or introducing slow-acting toxins—that would be difficult to detect immediately but would degrade the health of the targeted population or military forces.

3. Global Logistics Collapse

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the fragility of the “Just-in-Time” inventory model in healthcare. Hospitals typically hold only a few days of inventory. A disruption in global shipping—whether caused by another pandemic, a closure of the South China Sea, or port strikes—immediately impacts drug availability. The system lacks strategic stockpiles for the vast majority of civilian pharmaceuticals, meaning that a logistics failure translates directly into patient harm.

6. The Protocol of Trust: Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) & DNS

If Subsea Cables are the hardware of the internet, the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) and the Domain Name System (DNS) are the software logic that makes the network function. BGP determines the path data packets take to travel across the internet’s disparate networks (Autonomous Systems), while DNS acts as the address book, translating human-readable names (like google.com) into machine-routable IP addresses. Both protocols were designed in the 1980s, an era when the internet was a small academic network built on a foundation of mutual trust. That trust no longer exists, yet the protocols remain, creating a systemic vulnerability at the core of the digital world.

Why It Is Fragile

BGP is fragile because it lacks inherent security or validation mechanisms. When a network (Autonomous System) announces to the rest of the internet, “I know the path to this IP address,” the protocol is designed to believe it.

Trust-Based Routing

There is no centralized authority that validates BGP routes in real-time. A malicious actor—or simply a clumsy network administrator—can announce that they own an IP block that actually belongs to a bank, a government agency, or a grid operator. Because BGP favors specific routing metrics (often the shortest or most specific path), traffic intended for the legitimate destination is automatically rerouted to the hijacker. This is known as a BGP Hijack.16

DNS Centralization

While DNS is theoretically a distributed system, in practice, the authoritative “Root Servers” and the major commercial DNS providers represent centralized points of failure. The entire system relies on a hierarchy of trust starting from the Root Zone. If the integrity of the Root is compromised, or if the limited number of companies providing high-availability DNS services are taken offline, vast portions of the internet become unreachable. The user cannot “find” the website, even if the website is still online.17

Top Three Threats

1. BGP Hijacking and Route Leaks

Adversaries can deliberately hijack BGP routes to redirect U.S. government, military, or financial traffic through their own networks for the purpose of espionage or denial of service. By announcing a more specific route to a target’s IP address, an attacker can force the traffic to flow through their servers, where it can be copied, decrypted, or dropped. China Telecom has been accused in multiple instances of “misrouting” U.S. domestic traffic through points of presence in China for varying durations.18 These “route leaks” effectively expose internal U.S. communications to foreign surveillance on a massive scale.

2. DDoS Attacks Against Critical DNS Infrastructure

Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks targeting major DNS providers exploit the centralization of the sector. The 2016 attack on Dyn, a major DNS provider, utilized a botnet of insecure IoT devices to overwhelm Dyn’s servers. The result was that major platforms like Amazon, Netflix, Twitter, and Reddit became inaccessible to millions of users. The fragility lies in the fact that many critical services rely on a single DNS provider without redundancy. A sustained, nation-state-level DDoS attack on key DNS nodes could effectively sever the U.S. digital economy from the global internet.

3. Incomplete Adoption of RPKI

Resource Public Key Infrastructure (RPKI) is the cryptographic solution developed to fix the BGP trust issue. It allows networks to cryptographically sign their route announcements, proving ownership. However, adoption of RPKI is voluntary and remains incomplete. Many large networks and critical infrastructure operators have not fully deployed Route Origin Validation (ROV). As long as a significant portion of the internet continues to accept unsigned, unvalidated BGP announcements, the ecosystem remains vulnerable to cascading routing failures and hijacking.19 The “chain of trust” is only as strong as its weakest, unverified link.

7. The 25-Day Lifeline: Distillate Fuel Oil (Diesel) Logistics

To the digital native, the economy appears to run on data. In physical reality, it runs on diesel. Distillate fuel oil is the lifeblood of the nation’s logistics and emergency response capabilities. It powers the semi-trucks that deliver food to grocery stores, the freight trains that move commodities, the tractors that harvest crops, and the backup generators that keep hospitals and data centers alive when the grid fails. The United States operates on a razor-thin margin of diesel inventory, typically maintaining only 25 to 30 days of supply nationwide. This “Just-in-Time” energy model leaves virtually zero buffer for systemic shocks.

Why It Is Fragile

The fragility of the diesel supply chain is a result of refining capacity rationalization, regional imbalances, and pipeline dependencies.

Inventory Tightness

The U.S. refining sector has undergone significant contraction, with older refineries closing or converting to renewable diesel production, reducing the overall capacity to produce traditional distillates. Consequently, regional inventories—particularly on the East Coast (PADD 1)—frequently dip to critically low levels. In late 2022, East Coast diesel inventories hit 25 days of supply, the lowest level since 2008. This leaves the region vulnerable to any disruption; a major hurricane, a refinery fire, or a pipeline outage could deplete this buffer in weeks, leading to physical shortages.20

Food System Dependency

Modern industrial agriculture is entirely diesel-dependent. From planting to harvesting to transport, every step of the food production cycle requires diesel fuel. A shortage is not merely an inconvenience for commuters; it is a food security crisis. The “Just-in-Time” delivery of food to supermarkets (which typically hold only 3 days of stock) is predicated on the continuous operation of the trucking fleet. If diesel stops, the food supply chain halts immediately.21

Pipeline Bottlenecks

The distribution of refined products relies on a few major pipeline systems, most notably the Colonial Pipeline, which supplies nearly half of the fuel consumed on the East Coast. These pipelines are single points of failure for half the country’s population.

Top Three Threats

1. Pipeline Cyberattacks

The 2021 Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack was a watershed moment. It demonstrated that a cyberattack on the IT billing infrastructure of a pipeline operator could force the shutdown of OT pipeline operations. The result was panic buying, fuel shortages across the Southeast, and a stark realization of the lack of redundancy in fuel transport. Adversaries watched this event closely. A future attack, perhaps combined with physical sabotage of pumping stations, could block the primary artery of fuel to the East Coast for an extended duration, far exceeding the 25-day inventory buffer.

2. Refinery Capacity Loss and Accidents

The concentration of refining capacity in the Gulf Coast region exposes the national supply to weather events. A Category 5 hurricane that damages major refineries or the electrical infrastructure supporting them could take millions of barrels of daily capacity offline for months. Combined with the already low inventories, this would create a shock that the system cannot absorb, necessitating strict rationing of fuel for emergency services and agriculture.

3. Geopolitical Oil Shocks

While the U.S. is a major oil producer, the price of diesel is set globally, and the market is interconnected. A conflict in the Middle East or an expansion of embargoes involving Russian energy products can spike global prices. In such a scenario, U.S. refiners might be economically incentivized—or contractually obligated—to export diesel to higher-priced markets in Europe or Latin America, draining domestic supply. The Jones Act (Merchant Marine Act of 1920) further complicates resilience, as it restricts the ability to ship fuel from the Gulf Coast to the East Coast on foreign-flagged vessels during a crisis, creating artificial bottlenecks even if domestic fuel is available.

8. The Trojan Horse on the Docks: Ship-to-Shore Cranes (ZPMC)

U.S. ports are the gateways of the economy, handling the vast majority of overseas trade. The physical movement of containers from ship to shore is performed almost exclusively by giant gantry cranes. Approximately 80% of these ship-to-shore (STS) cranes currently in operation at U.S. ports are manufactured by a single company: Shanghai Zhenhua Heavy Industries Company Limited (ZPMC), a state-owned enterprise of the People’s Republic of China. Recent congressional investigations have discovered unauthorized communications equipment, including cellular modems, installed in these cranes, raising credible fears that they could serve as tools for espionage or sabotage.22

Why It Is Fragile

The fragility stems from a “hardware trojan” scenario combined with market dominance.

Monoculture and Dependency

The dominance of ZPMC creates a monoculture. A vulnerability or a backdoor in ZPMC’s software or hardware affects nearly every major U.S. port, including strategic hubs like the Port of Los Angeles, Long Beach, and Baltimore. The U.S. currently lacks a domestic manufacturer of large STS cranes, leaving port operators with few affordable alternatives.

Hidden Connectivity

These cranes are not dumb iron; they are sophisticated “smart” devices integrated into the port’s logistics networks to optimize loading and unloading. The discovery of cellular modems that were not part of the contract and which bypass port firewalls creates a direct, unmonitored link back to the manufacturer—and potentially to the Chinese intelligence services.23 This allows for data exfiltration or remote command execution without the port operator’s knowledge.

Top Three Threats

1. Remote Sabotage and Port Shutdown

In a conflict scenario, the PRC could potentially use the remote access capabilities to disable the cranes. Modern cranes rely on complex software to operate; a command sent via the hidden modems could corrupt the firmware or trigger safety lockouts, effectively turning the cranes into 2,000-ton statues. This would close U.S. ports, crippling the flow of military logistics (which often move through commercial ports) and civilian goods. The economic impact of shutting down the West Coast ports would be measured in billions of dollars per day.

2. Espionage and Logistics Tracking

The cranes are equipped with sophisticated sensors, cameras, and optical character recognition (OCR) systems to track containers. This data allows an adversary to monitor the flow of specific goods. By accessing this data stream, intelligence agencies could track U.S. military sustainment materiel, identify supply chain bottlenecks, or gain economic intelligence on the volume and type of U.S. trade. This transparency grants the adversary “information dominance” regarding U.S. logistics.

3. Lateral Movement into Port Networks

The cellular modems can serve as a beachhead or “backdoor” entry point into the port’s broader IT ecosystem. Once an adversary accesses the crane’s internal computer, they can potentially pivot laterally into the port’s Terminal Operating System (TOS). Compromising the TOS would allow attackers to manipulate cargo manifests, bypass customs screening for illicit cargo, or delete data on container locations, throwing the port’s inventory management into chaos.24

9. The Rolling Network: Freight Rail Signaling & Positive Train Control (PTC)

The U.S. freight rail network is a behemoth of efficiency, moving 40% of the nation’s long-distance tonnage. To address historical safety issues, the industry was mandated to adopt Positive Train Control (PTC), a complex system of wireless data links, GPS, and onboard computers designed to automatically stop trains to prevent collisions. While PTC has significantly improved safety, it has also fundamentally transformed the rail network from a mechanical system into a digital one, vastly expanding its cyber attack surface and introducing new fragilities.

Why It Is Fragile

PTC transforms trains into nodes on a network. The fragility lies in the wireless communications and the complexity of interoperability.

Wireless Dependency and Spectrum Risks

PTC relies on continuous radio communication between the locomotive, wayside interface units (WIUs) located along the track, and back-office servers. These signals transmit vital data about track authority and speed limits. The system operates on specific radio frequencies. If these links are disrupted—whether by jamming, interference, or equipment failure—the system is designed to “fail safe.” This means the trains stop. A widespread disruption of the wireless spectrum could therefore gridlock the entire network.25

Interoperability and Complexity

The U.S. rail network is highly interconnected; trains from one company (e.g., Union Pacific) frequently operate on tracks owned by another (e.g., CSX). This requires the PTC systems to be fully interoperable. A vulnerability in one railroad’s implementation or a compromised cryptographic key can theoretically propagate to others or be used to disrupt operations across shared corridors. The complexity of maintaining this interoperable “system of systems” creates numerous potential points of failure and software bugs that can be exploited.

Top Three Threats

1. Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) Attacks

Adversaries could attempt to intercept or manipulate the wireless communications between the wayside units and the train. By injecting false data—for example, signaling that a clear track is occupied, or vice versa—attackers could force trains to emergency brake (causing disruption and wear) or, in a worst-case scenario, disable the safety overlay to cause collisions. While PTC uses encryption, the management of keys and the security of the endpoints (radios) remain challenging.26

2. Ransomware on Control Centers

The “Back Office” servers that manage the PTC network and issue movement authorities are standard IT systems subject to standard IT threats. A ransomware attack on these servers—similar to the attacks seen in other sectors—would force the railroad to halt operations. Under federal regulations, trains cannot operate on PTC-mandated mainlines without an active PTC system. Therefore, a cyberattack on the office network becomes a physical stop-order for the trains.

3. Jamming of Wayside Signals

Because the system relies on wireless transmission, it is vulnerable to RF jamming. An adversary using relatively simple, high-power transmitters near key rail junctions or marshaling yards could jam the PTC frequencies. This would blind the trains to the status of the signals ahead, triggering automatic stops. A coordinated jamming campaign across multiple key nodes (e.g., Chicago, Kansas City) could paralyze the national rail flow, halting the movement of grain, coal, and chemicals.

10. The Liquidity Core: Wholesale Payment Systems (FedWire/CHIPS)

While the consumer public focuses on the interfaces of Venmo, Zelle, or credit cards, the U.S. economy actually runs on the wholesale payment systems: FedWire (operated by the Federal Reserve) and CHIPS (The Clearing House Interbank Payments System). These systems settle trillions of dollars in transactions every single day. They are the plumbing of the global financial system. If they stop, liquidity freezes instantly; banks cannot pay each other, corporate payrolls fail, and the economy suffers the equivalent of a cardiac arrest.

Why It Is Fragile

The fragility of the wholesale payment system is defined by extreme concentration risk and the lack of viable manual alternatives.

Concentration of Value

A staggering volume of value flows through a very small number of digital nodes. FedWire is effectively a single point of failure for the U.S. dollar system. While the Federal Reserve maintains backup data centers, the system is unitary. If the FedWire application suffers a logic failure or a corrupted update, there is no other system capable of processing the volume and value of transactions it handles.

Operational Opacity and Interdependency

The system is deeply interconnected with SWIFT (for messaging) and the internal ledgers of thousands of banks. A corruption of data in one part of the chain can propagate. Unlike a physical theft where money is gone, a “data integrity” failure is more insidious: the money is there, but no one knows who owns it. Recovering from a corruption of the ledger is exponentially harder than recovering from a power outage, as it requires manual reconciliation of millions of transactions.

Top Three Threats

1. Data Integrity Attacks

The most feared scenario in financial cybersecurity is not the theft of funds, but the alteration of data. An adversary who gains access to the payment gateways could alter transaction amounts, recipients, or timestamps. This would destroy trust in the system. If banks cannot trust the balances shown on their screens, they will stop lending and settling immediately.27 This “trust freeze” would trigger a liquidity crisis similar to 2008 but at the speed of light, potentially crashing markets before human intervention is possible.

2. Operational Outages and “Glitches”

The system is vulnerable to its own complexity. Disruptions in 2019 and 2021 caused FedWire to go offline for several hours due to internal technical errors.28 While these were resolved without systemic collapse, they occurred during relatively calm market conditions. If such an outage were to occur during a moment of high financial stress (e.g., a major bank failure or geopolitical crisis), the inability to move liquidity for even a few hours could amplify market panic, leading to bank runs and a systemic meltdown.

3. Post-Quantum Cryptography (The “Q-Day” Threat)

Financial systems rely entirely on public-key cryptography to secure transactions and verify identities. The development of a cryptographically relevant quantum computer (CRQC) by an adversary would render current encryption standards (like RSA) obsolete. This is the “Q-Day” scenario. If an adversary could decrypt FedWire traffic or spoof digital signatures, they could dismantle the financial system at will. While the transition to Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) is underway, it is a slow process, and “harvest now, decrypt later” attacks mean that encrypted data stolen today could be weaponized in the future.29

Conclusion

The ten infrastructure services detailed in this report are not merely “at risk” in the abstract sense; they are currently operating with systemic vulnerabilities that adversaries have already mapped, probed, and in some cases, actively compromised. The transition of the United States to a digital, interconnected, and hyper-efficient society has created a new threat landscape. We have moved from a world where threats were visible and kinetic to one where a software update in a solar wind monitoring tool, a cut cable in the dark depths of the Atlantic, or a jammed radio signal in the Midwest can trigger nationwide paralysis.

The fragility we face is structural. It stems from a decades-long strategic decision to prioritize efficiency—defined by Just-in-Time delivery, the lowest bidder procurement, and remote automated management—over resilience—defined by inventory buffers, redundancy, and manual override capabilities.

To address these threats, the United States must fundamentally shift its national security paradigm. We must treat the GPS signal with the same reverence and defensive priority as we do our physical borders: it is a sovereign asset that must be defended. We must view the supply of transformers and antibiotics as we do our strategic oil reserves: essential buffers against catastrophe that cannot be left solely to the whims of the global market.

Failure to harden these invisible services will leave the United States vulnerable to a new form of coercion—one where an adversary need not defeat our military on the battlefield, but simply turn off the lights, poison the water, and halt the flow of commerce from the comfort of a keyboard. The glass jaw must be protected before the punch is thrown.

Appendix A: Methodology

This strategic assessment employs a qualitative risk analysis framework tailored to identify “High-Impact, Low-Probability” (HILP) vulnerabilities within the United States critical infrastructure ecosystem. The methodology prioritizes the identification of structural fragilities rather than transient threats. The selection of the top ten critical services was based on a synthesis of open-source intelligence (OSINT), including unclassified government reports (DHS, DOE, CISA, FBI), congressional testimony, industry white papers, and academic research.

Selection Criteria

Services were evaluated and ranked based on four primary “Fragility Indicators”:

- Single Point of Failure (SPOF): The existence of a central node, protocol, or geographic location whose failure results in total system collapse (e.g., GPS timing, FedWire).

- Lack of Redundancy/Substitutability: The absence of viable manual backups or alternative supply chains that can be activated within a crisis-relevant timeframe (e.g., LPT manufacturing, API synthesis).

- Opacity: The degree to which the infrastructure is invisible to regulators or operators, creating “blind spots” in risk management (e.g., Subsea cable ownership, ZPMC crane modems).

- Cross-Sector Interdependency: The extent to which a failure in one sector cascades into others (e.g., Diesel shortages halting food logistics).

Threat Modeling

For each identified service, a threat model was applied to categorize risks into three domains:

- Kinetic/Physical: Direct attacks on hardware (cutting cables, shooting transformers).

- Cyber/Digital: Exploitation of software, firmware, or network protocols (BGP hijacking, SCADA ransomware).

- Geopolitical/Supply Chain: State-level coercion through export controls, manufacturing monopolies, or regulatory warfare.

This report relies on data available as of early 2026, incorporating recent legislative findings and incident reports from 2024 and 2025 to reflect the most current threat landscape.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- An Evaluation of Dependencies of Critical Infrastructure Timing Systems on the Global Positioning System (GPS) – GPS.gov, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.gps.gov/sites/default/files/2025-07/NIST.TN_.2189.pdf

- America’s Asymmetric Vulnerability to Navigation Warfare: Leadership and Strategic Direction Needed to Mitigate Significant Threats – National Security Space Association, accessed January 13, 2026, https://nssaspace.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/NAVWAR-FINAL.pdf

- On GPS spoofing of aerial platforms: a review of threats, challenges, methodologies, and future research directions – PubMed Central, accessed January 13, 2026, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8114815/

- U.S. Department of Energy Large Power Transformer Resilience Report to Congress, July 2024, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2024-10/EXEC-2022-001242%20-%20Large%20Power%20Transformer%20Resilience%20Report%20signed%20by%20Secretary%20Granholm%20on%207-10-24.pdf

- How Long Does It Take to Replace a Power Transformer, accessed January 13, 2026, https://evernewtransformer.com/how-long-does-it-take-to-replace-a-power-transformer/

- Addressing the Critical Shortage of Power Transformers to Ensure Reliability of the U.S. Grid – CISA, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/2024-06/DRAFT_NIAC_Addressing%20the%20Critical%20Shortage%20of%20Power%20Transformers%20to%20Ensure%20Reliability%20of%20the%20U.S.%20Grid_Report_06052024_508c.pdf

- About 400 exposed web-based US water facility interfaces, as coordinated remediation effort underway – Industrial Cyber, accessed January 13, 2026, https://industrialcyber.co/industrial-cyber-attacks/about-400-exposed-web-based-us-water-facility-interfaces-as-coordinated-remediation-effort-underway/

- Compromise of U.S. Water Treatment Facility – CISA, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa21-042a

- Ongoing Cyber Threats to U.S. Water and Wastewater Systems | CISA, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa21-287a

- Subsea Cables and US National Security – Steptoe, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.steptoe.com/en/news-publications/stepwise-risk-outlook/subsea-cables-and-us-national-security.html

- The Silent War Beneath the Arctic Seas: Why Securing Undersea Cables is a National Security Imperative, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.trumanproject.org/truman-view-blog/the-silent-war-beneath-the-arctic-seas

- The U.S. Should Get Serious About Submarine Cable Security, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.cfr.org/blog/us-should-get-serious-about-submarine-cable-security

- Safeguarding Pharmaceutical Supply Chains in a Global Economy – 10/30/2019 | FDA, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/congressional-testimony/safeguarding-pharmaceutical-supply-chains-global-economy-10302019

- A Bitter Pill: America’s Dangerous Dependence on China-Made Pharmaceuticals – Exiger, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.exiger.com/perspectives/a-bitter-pill-america-dependence-on-china-made-pharmaceuticals/

- SECTION 3: GROWING U.S. RELIANCE ON CHINA’S BIOTECH AND PHARMACEUTICAL PRODUCTS, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2019-11/Chapter%203%20Section%203%20-%20Growing%20U.S.%20Reliance%20on%20China%E2%80%99s%20Biotech%20and%20Pharmaceutical%20Products.pdf

- BGP case studies that illustrate the crucial BGP vulnerability, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.bgp.us/case-studies/

- BGP, DNS, and the Fragility of our Critical Systems | F5 Labs, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.f5.com/labs/articles/bgp-dns-and-the-fragility-of-our-critical-systems

- China’s Breach of U.S. Telecoms: A Cyber Wake-Up Call – CYE, accessed January 13, 2026, https://cyesec.com/blog/chinas-breach-of-u-s-telecoms-a-cyber-wake-up-call

- FIxing BGP’s security problems is not proving to be easy – The Register, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.theregister.com/2025/08/27/systems_approach_securing_internet_infrastructure/

- Inventory Concerns Take Center Stage as Diesel Days of Supply Drop Below 30, accessed January 13, 2026, https://mansfield.energy/2025/07/22/inventory-concerns-take-center-stage-as-diesel-days-of-supply-drop-below-30/

- Threats to Food and Agriculture Resources – Homeland Security, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/threats_to_food_and_agriculture_resources.pdf

- US House Committees reveal Chinese-manufactured cargo equipment at ports pose cyber, espionage threats, accessed January 13, 2026, https://industrialcyber.co/transport/us-house-committees-reveal-chinese-manufactured-cargo-equipment-at-ports-pose-cyber-espionage-threats/

- US Congressional probe finds communications gear on Chinese cranes in US ports | Paladin Risk Solutions, accessed January 13, 2026, https://paladinrisksolutions.com/bluesky/us-congressional-probe-finds-communications-gear-on-chinese-cranes-in-us-ports/

- Investigation by Select Committee on the CCP, House Homeland Finds Potential Threats to U.S. Port Infrastructure Security from China, accessed January 13, 2026, https://chinaselectcommittee.house.gov/media/reports/investigation-select-committee-ccp-house-homeland-finds-potential-threats-us-port

- Critical Railroad-Signaling Flaw Could Disrupt U.S. Rail Traffic – Alliant Insurance Services, accessed January 13, 2026, https://engage.alliant.com/ITPE0825/article-4-8505T-3018PC.html

- Positive Train Control (PTC) Expands Cyber Attack Surface for Rail Systems – Dragos, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.dragos.com/blog/positive-train-control-ptc-expands-cyber-attack-surface-for-rail-systems

- Cyber-Security Risks of Fedwire – Scholarly Commons, accessed January 13, 2026, https://commons.erau.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1590&context=jdfsl

- Operational Resilience in Digital Payments: Experiences and Issues, WP/21/288, December 2021, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.imf.org/-/media/files/publications/wp/2021/english/wpiea2021288-print-pdf.pdf

- KETS warns US on quantum plan, urges PQC plus QKD mix, accessed January 13, 2026, https://securitybrief.co.uk/story/kets-warns-us-on-quantum-plan-urges-pqc-plus-qkd-mix

- Infrastructure Resilience Planning Framework (IRPF) – CISA, accessed January 13, 2026, https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/2025-03/IRPF_3.17.2025.pdf

- Joint Statement on the Security and Resilience of Undersea Cables in a Globally Digitalized World – State Department Home, accessed January 13, 2026, https://2021-2025.state.gov/joint-statement-on-the-security-and-resilience-of-undersea-cables-in-a-globally-digitalized-world/