On September 22, 1979, at 00:53:00 UTC, the orbital vigilance of the Cold War was pierced not by a Soviet salvo, but by a silent, distinct signature from the desolate waters of the South Indian Ocean. The United States Air Force satellite Vela 6911, an aging sentinel designed to monitor compliance with the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT), registered a “double flash” of light. To the silicon bhangmeters onboard, the signal was unmistakable: the unique optical fingerprint of an atmospheric nuclear explosion. This event, designated Alert 747, did not trigger a war, but it did ignite a fierce internecine conflict within the United States government—a battle between empirical intelligence and political expediency that would define the latter half of the Carter Administration.1

The resulting controversy, known as the Vela Incident, stands as a seminal case study in the intersection of nuclear non-proliferation enforcement, diplomatic realism, and the politicization of scientific intelligence. For decades, the official narrative maintained ambiguity, suggesting the event was likely a meteoroid impact or a sensor glitch. However, an exhaustive review of declassified intelligence memoranda, scientific analyses, and historical archives suggests a different reality: a covert nuclear test conducted by Israel, likely with the logistical collaboration of apartheid South Africa. The incident reveals the fragility of international arms control regimes when their enforcement threatens broader geopolitical interests, specifically the ratification of the SALT II treaty and the preservation of Middle Eastern peace accords.2

Part I: The Architecture of Vigilance

The Origins of Project Vela

To understand the gravity of Alert 747, one must first appreciate the architecture of surveillance that detected it. The Vela program was born from the necessity of trust through verification. Following the Cuban Missile Crisis and the signing of the Limited Test Ban Treaty (LTBT) in 1963, the United States required a mechanism to monitor nuclear testing in the atmosphere, underwater, and in outer space.4 The treaty prohibited signatories from conducting nuclear explosions in these environments, driving the superpowers to underground testing. However, the fear of clandestine violations—particularly by emerging nuclear states or non-signatories—remained acute.

The Vela satellites were the first space-based observation devices jointly developed by the U.S. Air Force and the Atomic Energy Commission.4 While early generations focused on X-ray and gamma-ray detection, the “Advanced Vela” satellites (Vela 5 and 6 series) launched in the late 1960s were equipped with a crucial innovation: the “bhangmeter.”

The Bhangmeter and the Physics of Light

The bhangmeter was a silicon photodiode sensor designed to detect the specific optical signature of a nuclear fireball. Its name, derived whimsically from the Hindi word for cannabis (“bhang”), alluded to the idea that one would have to be intoxicated to believe such a sensor would work, yet it proved remarkably effective.5

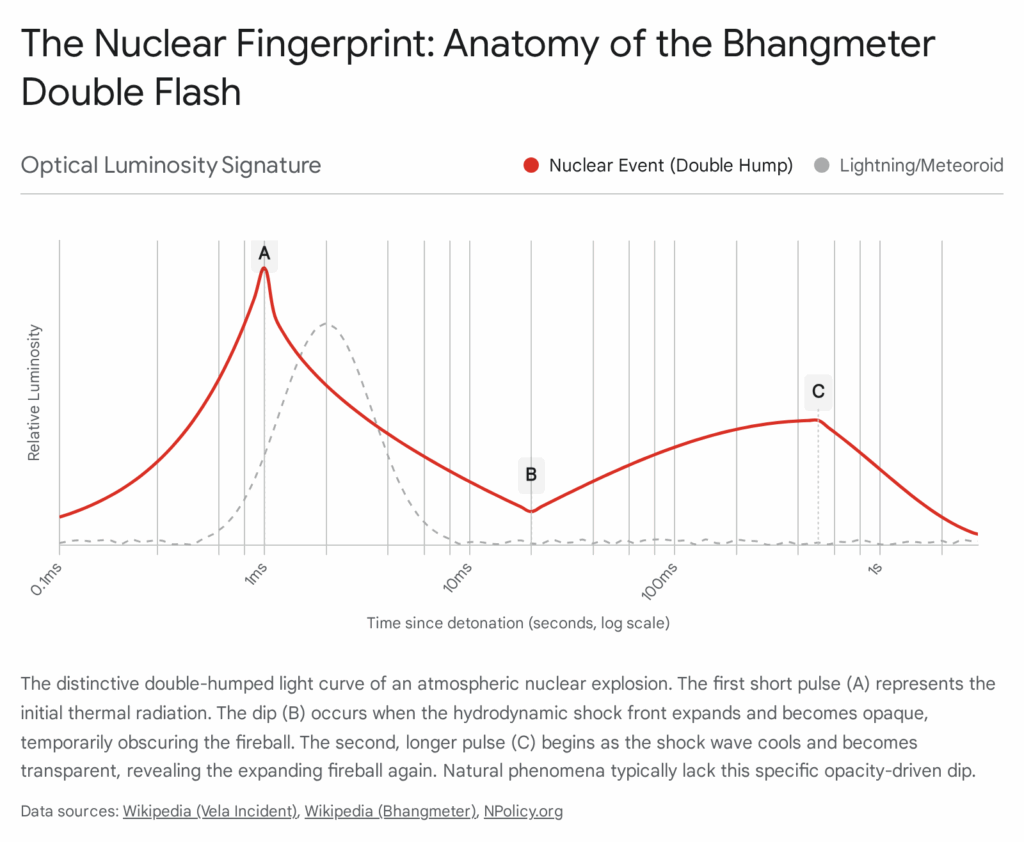

The physics of an atmospheric nuclear explosion creates a unique temporal light signature known as the “double flash,” which the bhangmeters were calibrated to recognize:

- Pulse I (The Thermal Spike): Upon detonation, the nuclear device releases a massive burst of thermal X-rays. These X-rays are absorbed by the air immediately surrounding the device, heating it to incandescence and creating an intensely bright flash that lasts only a millisecond.

- The Minimum (Hydrodynamic Obscuration): As the fireball expands, a hydrodynamic shock front forms at its boundary. This shock wave compresses the air to such a density that it becomes opaque to visible light. This opaque shell effectively masks the glowing fireball inside, causing the detected luminosity to drop precipitously.

- Pulse II (Fireball Re-emergence): As the shock wave expands further, its temperature and density drop. Eventually, the shock front becomes transparent again (“breakaway”), revealing the fireball which is still expanding and radiating heat. This results in a second, much longer, and more massive pulse of light that builds to a maximum before decaying.2

This double-humped curve—bright flash, sudden dimming, and slow re-brightening—is the “heartbeat” of a nuclear explosion. Natural phenomena like lightning (a single spike) or meteoroids (an impact flash) do not replicate this specific hydrodynamic obscuration sequence. By 1979, Vela satellites had detected 41 previous double flashes. In every single case, the signal was subsequently confirmed as a nuclear test.1

The Sentinel: Vela 6911

The satellite that detected Alert 747, Vela 6911 (also known as Vela 5B), was launched on May 23, 1969.1 By September 1979, it was ten years old—seven years past its design lifetime of three years. Despite its age, the satellite’s sensors were functional and had successfully tracked French and Chinese atmospheric tests throughout the decade. On the night of September 22, it was orbiting at an altitude of approximately 67,000 miles, holding a field of view that encompassed a 3,000-mile diameter circle covering the southern tip of Africa, the Indian Ocean, the South Atlantic, and parts of Antarctica.1 It was a lonely vigil; other satellites in the constellation were either retired or not positioned to view the southern hemisphere at that specific moment, leaving Vela 6911 as the sole optical witness.

Part II: The Geopolitical Tinderbox (1977–1979)

The detection of a nuclear flash did not occur in a vacuum; it struck a world wired for tension. The Carter Administration was navigating a precarious diplomatic landscape where the non-proliferation regime was clashing with the strategic necessities of the Cold War.

The Stalled SALT II Treaty

By late 1979, the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks II (SALT II) treaty was the centerpiece of President Jimmy Carter’s foreign policy legacy. Signed in Vienna in June 1979 by Carter and Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, the treaty aimed to limit the growth of nuclear arsenals. However, ratification required a two-thirds majority in the U.S. Senate, where it faced fierce skepticism.6

Hawkish senators, including John Glenn and Frank Church, were deeply concerned about the Soviet Union’s adherence to previous agreements and the ability of the U.S. to verify compliance.7 Senator Glenn, chair of the Subcommittee on Energy, Nuclear Proliferation and Federal Services, was particularly focused on verification technologies. If the administration admitted that an unknown actor could detonate a nuclear weapon without the U.S. being able to definitively identify the perpetrator or prove the violation, confidence in the verification regime—and by extension, SALT II—would collapse. The administration simply could not afford a “mystery” nuclear test.2

The Axis of Isolation: Israel and South Africa

While Washington focused on Moscow, a clandestine strategic alignment was solidifying in the Southern Hemisphere. Both Israel and South Africa faced deepening international isolation. South Africa, under the apartheid regime of P.W. Botha, was subject to a mandatory UN arms embargo (Resolution 418) adopted in 1977.2 Israel, though an American ally, found itself increasingly isolated following the 1973 Yom Kippur War and was acutely aware of its lack of strategic depth.

Intelligence declassified decades later indicates that this shared isolation bred a “survivalist” symbiosis. Documents reveal a 1975 secret defense agreement signed by Israeli Defense Minister Shimon Peres and South African Defense Minister P.W. Botha.9 This agreement facilitated military cooperation that likely extended to nuclear technology. South Africa possessed vast uranium reserves and open spaces for testing, specifically the Kalahari test site which had been prepared for a cold test in 1977 before being discovered by Soviet and U.S. satellites.11 Israel, in turn, possessed advanced weapons design capabilities and delivery systems, specifically the Jericho missile technology.13

By 1979, Israel faced a strategic dilemma. The development of the Jericho II missile required a warhead. Some analysts, including former nuclear weapons designer Thomas Reed, suggest that Israel needed to test a specific type of low-yield device, possibly a neutron bomb or a miniaturized tactical weapon, to ensure the viability of its deterrent.2 South Africa, seeking its own deterrent against what it perceived as a Soviet-backed “Total Onslaught” from neighboring states, was a willing partner.

Part III: The September Flash

The Event Timeline

At 00:53:00 UTC on September 22, 1979, the two bhangmeters on Vela 6911 triggered. The signal intensity indicated a low-yield explosion, estimated between 2 and 3 kilotons.15 This was small by Cold War standards—Hiroshima was 15 kilotons—but consistent with a tactical weapon or a fission trigger for a thermonuclear device.

The location was triangulated to a remote area of the South Indian Ocean, roughly situated between the Prince Edward Islands (South African territory) and the Crozet Islands (French territory).2 This region is known for the “Roaring Forties,” an area of persistent high winds and cloud cover, which would help scrub radioactive debris from the atmosphere and mask the visual signature from surface observers. Notably, the test coincided with a typhoon in the region, further suggesting a deliberate attempt to use weather as cover.2

The Immediate Reaction: “High Confidence”

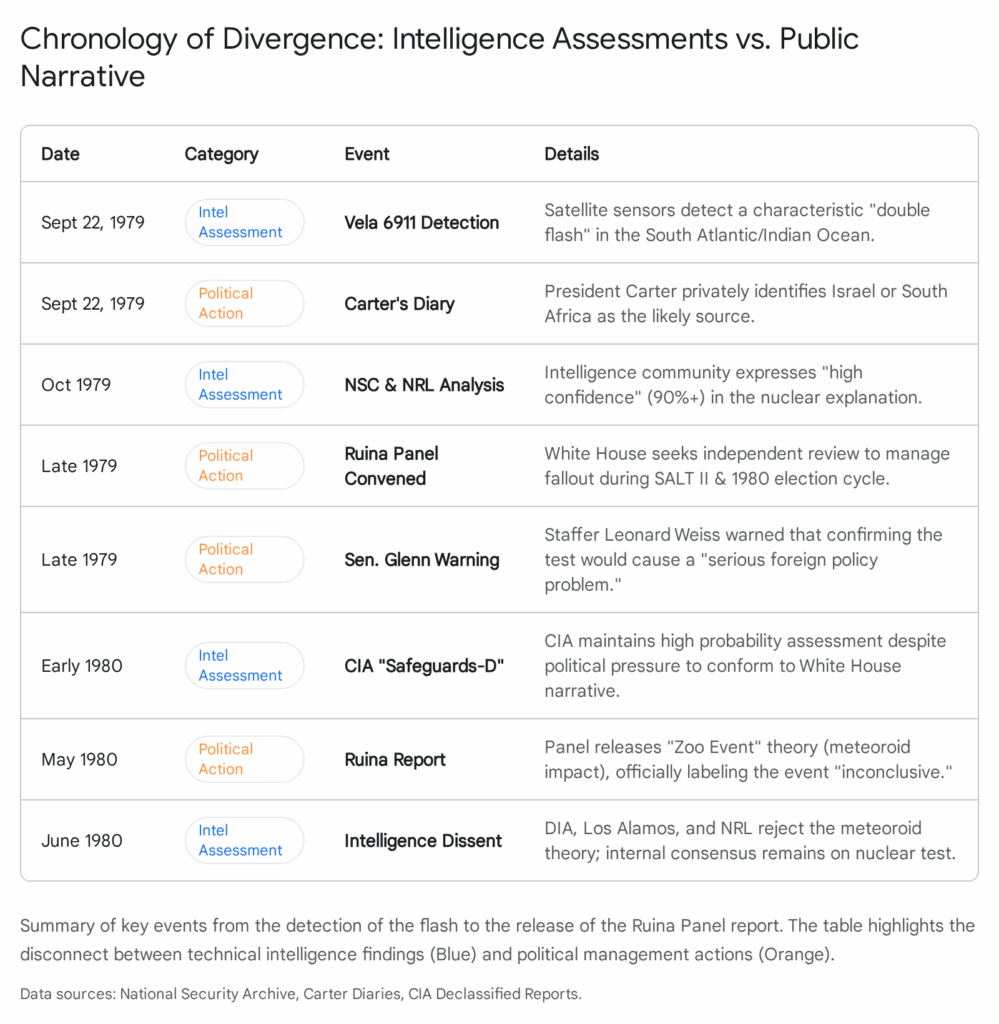

In the days following the detection, the U.S. Intelligence Community (IC) mobilized. The initial assessment was unambiguous. The CIA, the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), and the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) all assessed with high confidence that a nuclear event had occurred. A CIA memo from later that year estimated a “90% plus” probability of a nuclear test.16 The DIA’s Jack Varona argued that the signal was distinct and could not be explained by natural phenomena.11

President Carter was informed immediately. His diary entry from September 22, 1979, reads: “There was indication of a nuclear explosion in the region of South Africa—either South Africa, Israel using a ship at sea, or nothing.” This entry reveals that the President’s first instinct—and the first intelligence briefing he received—pointed directly at the most likely suspects.17

Part IV: The Triad of Evidence

While the Vela signal (Alert 747) was the primary trigger, it was not the sole data point. A forensic reconstruction of the timeline reveals a triad of corroborating evidence that the intelligence community recognized, even if it was publicly minimized.

1. Hydroacoustic Signatures

The most compelling corroboration came from the ocean depths. The U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) analyzed data from the Missile Impact Locating System (MILS) and other hydroacoustic sensors (underwater microphones) monitored by the Air Force Technical Applications Center (AFTAC). Sensors near Ascension Island and other classified locations detected a distinct acoustic signal originating from the vicinity of the Prince Edward Islands that matched the exact time of the Vela flash.11

Sound travels efficiently through the SOFAR channel in the ocean, allowing detection over thousands of miles. NRL Director Dr. Alan Berman later stated that the signal was “unique to nuclear shots in a maritime environment” and was the strongest hydroacoustic pulse he had ever seen from that region.16 The NRL’s internal report concluded that the hydroacoustic evidence strongly suggested a nuclear test had taken place. However, because the signal reflected off the Antarctic ice shelf or ocean floor features, there was some debate about the precise location of the surface burst, a gap that later skeptics would exploit.17

2. Ionospheric Disturbances

In Puerto Rico, the Arecibo Observatory detected an anomalous traveling ionospheric disturbance (TID) moving from southeast to northwest on the morning of September 22.2 Nuclear explosions generate a shockwave that propagates up into the ionosphere, creating ripples in electron density that can be detected by radar. The timing and vector of the disturbance detected at Arecibo were consistent with a shockwave originating in the South Atlantic/Indian Ocean basin at the time of the Vela flash. This provided a second physical medium (the upper atmosphere) corroborating the satellite (optical) and hydroacoustic (underwater) data.16

3. The Search for Debris (The “Missing” Smoking Gun)

The standard confirmation for any nuclear test is the detection of radioactive fallout. The U.S. Air Force immediately launched WC-135 sorties to sample the air in the southern hemisphere. These flights found no radioactive debris. The lack of immediate debris became the primary argument for the skeptics.21 However, the search was hampered by the immense size of the search area and the delay in deploying aircraft. A low-yield surface burst in the ocean would produce less fallout than a ground burst, and the typhoon conditions could have washed out particulates (rainout) before they reached the sampling altitude.

Crucially, it would be decades before the biological archive revealed what the planes missed. As discussed in Part VII, iodine-131 was eventually found in sheep thyroids in Australia, but this data was not fully integrated into the public narrative in 1979.22

Part V: The Crisis in Washington

The Intelligence Consensus vs. The Political Imperative

The internal assessment of the U.S. government in late 1979 was a study in cognitive dissonance. The operational level of intelligence—the scientists at Los Alamos, the analysts at the CIA, and the engineers at NRL—viewed the event as a confirmed test. A “mini-SCC” (Special Coordinating Committee) meeting on January 9, 1980, reviewed the data. Despite the consensus among technical agencies, the political leadership, represented by National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski and White House staffers, pushed for a verdict of uncertainty.16

The motivation was clear. If the President declared a nuclear violation:

- Sanctions: Under the 1977 Symington Amendment and Glenn Amendment, the U.S. would be legally obligated to impose draconian sanctions on the perpetrator. Sanctioning Israel would destroy the Camp David peace framework, the administration’s crowning diplomatic achievement. Sanctioning South Africa would derail delicate negotiations regarding the independence of Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) and Namibia, areas where the U.S. needed Pretoria’s cooperation.21

- SALT II Vulnerability: Admitting that the Vela satellites detected a test that the U.S. could not “prove” or attribute would hand ammunition to SALT II opponents. Senators like Frank Church would argue that if the U.S. couldn’t identify a test by a minor power, how could it verify Soviet compliance with complex missile limits?.2

The “Whitewash” Strategy

The White House response, led by Science Adviser Frank Press, shifted from investigation to containment. Press convened an ad hoc panel of non-government scientists to review the Vela data. This body, which became known as the Ruina Panel, was viewed with deep suspicion by the intelligence community. An internal memo from the time noted that the White House seemed only interested in hearing dissenting views “so that we can more safely ignore [the nuclear conclusion]”.16

This strategy effectively bifurcated the truth: there was the classified reality, where intelligence agencies operated on the assumption of a joint Israeli-South African test, and the public narrative, which aggressively promoted ambiguity and natural explanations.

Part VI: The Ruina Panel and the “Zoo Event” Theory

The Panel’s Mandate and Composition

The Ad Hoc Panel on the September 22 Event was chaired by Dr. Jack Ruina of MIT, a former head of ARPA. It included distinguished scientists such as Richard Garwin (IBM), Luis Alvarez (Nobel laureate), and Wolfgang Panofsky (Stanford).1 The panel was tasked with reviewing the data to determine if a nuclear explosion was the only possible explanation.

Critically, the panel was not an investigative body with its own data-gathering capabilities; it was a review board that assessed data provided to it. However, witnesses later claimed the panel was selective in what it weighed heavily. NRL Director Alan Berman felt the panel dismissed his hydroacoustic data because it didn’t fit their preferred narrative, describing their treatment of the evidence as “incomplete” and “ambiguous”.20

The Meteoroid Hypothesis

In July 1980, the Ruina Panel released its findings. It concluded that the signal was “probably not” a nuclear explosion. Instead, they proposed that the signal was likely an artifact of a “zoo event”—a term used to describe inexplicable sensor anomalies in the complex environment of space.

The specific mechanism they proposed was a micrometeoroid impact. The panel hypothesized that a small meteoroid had struck the satellite, ejecting a cloud of debris. This debris, they argued, could have reflected sunlight into the bhangmeters in a way that mimicked the double flash. They suggested that the first pulse was the impact itself, and the second pulse was the reflection off the expanding debris cloud.1

The Scientific Critique: “One in One Hundred Billion”

The “Zoo Event” conclusion was met with immediate and withering criticism from defense scientists who managed the satellite program.

- Statistical Improbability: Researchers at Mission Research Corporation calculated the probability of a meteoroid striking the satellite at the precise angle and velocity to create a false “double pulse” signature that perfectly matched the timing of a nuclear explosion. The odds were calculated to be less than one in one hundred billion.1

- Sensor Discrepancy: The Vela satellite had two bhangmeters. For a debris cloud to fool both sensors simultaneously and identically, the geometry of the impact would have to be miraculously precise. The Ruina panel argued that the signals were slightly different, supporting the debris theory, while the Los Alamos team argued the differences were within calibration tolerances for a nuclear event.23

- The “Previous 41” Argument: There had been 41 previous double flashes detected by Vela satellites. Every single one had been a confirmed nuclear test. There was no precedent for a “false positive” double flash of this quality.2

Despite these objections, the Ruina Panel’s report gave the Carter Administration exactly what it needed: a scientific stamp of “inconclusive.” This allowed the White House to state that “no corroborating evidence” existed, effectively closing the book on the incident for the public, even as the CIA continued to track the Israeli nuclear program with high concern.17

Part VII: The Smoking Gun (Forensic Re-evaluation)

The “ambiguity” constructed by the Ruina Panel has largely eroded in the decades since, dismantled by new scientific studies and declassified admissions.

The Australian Sheep Connection

The most significant post-Cold War forensic breakthrough came in 2018. Researchers Lars-Erik De Geer and Christopher Wright published a definitive study in the journal Science & Global Security. They revisited a forgotten dataset: the thyroids of sheep slaughtered in Melbourne, Australia, in late 1979.22

Sheep thyroids are excellent bio-accumulators of Iodine-131, a short-lived radioactive isotope (half-life of 8 days) that is a primary product of nuclear fission. Because Iodine-131 decays so quickly, its presence is a timestamp; it cannot be a remnant of old tests from the 1960s. The researchers found a spike in Iodine-131 in samples taken in November 1979. Using advanced meteorological modeling, they backtracked the wind patterns from Victoria, Australia. The models showed that air masses passing over the Prince Edward Islands on September 22 would have reached southeastern Australia just as the rain washed the fallout onto the grazing pastures.24

This finding provided the “smoking gun” that the Ruina Panel claimed was missing. The combination of the optical flash, the hydroacoustic signal, and the radionuclide trace creates a closed loop of evidence that is statistically impossible to attribute to natural causes.

The Israeli Neutron Bomb Theory

The question remains: what exactly was tested? Historical analysis suggests it was not a standard fission bomb. Thomas Reed, in his book The Nuclear Express, argues that the device was likely an Israeli neutron bomb (enhanced radiation weapon).2

A neutron bomb is designed to maximize lethal radiation while minimizing blast and heat. Such a device would produce a lower explosive yield (consistent with the 2-3 kiloton estimate) and a smaller hydroacoustic footprint, potentially explaining why the acoustic signal was debated. However, it would still emit the intense X-rays necessary to trigger the bhangmeters. Reed posits that the Israelis, aware of the Vela satellite’s orbit (information likely obtained through intelligence channels), timed the test for a gap in coverage, not realizing that the “retired” Vela 6911 was still listening. The test was further masked by conducting it during a typhoon, using the storm front to scavenge particulate fallout before it could spread globally—a strategy that largely worked, except for the traces found in Australian sheep.2

The South African “Salute”

The political dimension of the test has also clarified. Following the end of apartheid, information regarding South Africa’s nuclear program began to surface. In 1997, South African Deputy Foreign Minister Aziz Pahad was quoted in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz confirming the event was a “salute” by the apartheid regime’s nuclear program.2 While his office later issued a clarification stating he was repeating rumors, the statement aligns with the known timeline of the “Arniston” missile tests.

The CIA had long tracked the “Arniston” facility, where South Africa and Israel cooperated on the development of the Jericho II missile (a medium-range ballistic missile). A nuclear test in 1979 would fit perfectly with the development cycle of a warhead for this delivery system.27 The collaboration provided Israel with the testing ground it lacked and South Africa with the missile technology it coveted.

Part VIII: Conclusions and Lessons Learned

The Vela Incident of 1979 was not a mystery; it was a secret. The preponderance of evidence—optical, hydroacoustic, ionospheric, and radiological—points to a low-yield nuclear test conducted by Israel with South African logistical support. That the United States government chose to officially label it “inconclusive” offers profound lessons for the contemporary analyst.

1. The Limits of Technical Verification

The Vela incident demonstrated that technical verification is necessary but insufficient. The satellite worked. The hydrophones worked. The scientists analyzed the data correctly. Yet, the detection was effectively nullified by political will. Verification is not just a scientific challenge; it is a political one. If a government is determined to ignore a violation to preserve a broader strategic relationship or treaty (in this case, SALT II and the Camp David Accords), it can manufacture enough ambiguity to paralyze the enforcement mechanism.

2. The “Ostrich Strategy” in Non-Proliferation

The Carter Administration’s response illustrates a recurring theme in U.S. non-proliferation policy: the “Ostrich Strategy.” When faced with a violation by a strategic ally or in a context that threatens broader goals, administrations may choose to look away. This ambiguity preserves short-term diplomatic frameworks but erodes the long-term credibility of the non-proliferation regime. The failure to call out the 1979 test arguably emboldened other proliferators, signaling that the U.S. might prioritize geopolitical expediency over strict enforcement.

3. The Persistence of Nuclear Shadows

The incident highlights the long tail of nuclear secrecy. It took nearly forty years for open-source science (meteorology and independent radionuclide analysis) to catch up with the classified assessments of 1979. This lag suggests that other “unresolved” proliferation events may currently be hidden behind similar veils of political ambiguity.

4. The Danger of “Politicized Science”

The Ruina Panel stands as a cautionary tale of how scientific inquiry can be channeled to support a pre-determined political conclusion. By framing the mandate narrowly and selecting panelists who were skeptical of the initial intelligence, the White House was able to generate a “scientific” counter-narrative that neutralized the intelligence community’s consensus. For the analyst, this underscores the importance of distinguishing between raw technical data (which pointed to a bomb) and high-level policy reports (which pointed to a meteoroid).

In the final analysis, Vela 6911 did its job. It saw the flash. The failure was not in the silicon eyes of the satellite, but in the political will of the men who read the data.

Works cited

- The Vela Incident: Nuclear Test or Meteorite? – The National Security Archive, accessed December 24, 2025, https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB190/index.htm

- Vela incident – Wikipedia, accessed December 24, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vela_incident

- Israel’s 1979 Nuclear Test and the US Government’s Attempt to Cover It Up, accessed December 24, 2025, https://www.npolicy.org/article.php?aid=647&rid=4

- Bhangmeter – Wikipedia, accessed December 24, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bhangmeter

- The Case for an Israeli Nuclear Test – Nonproliferation Policy Education Center, accessed December 24, 2025, https://npolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Moving_Beyond_Pretense-Ch13_Weiss.pdf

- Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT II) – U.S. Department of State, accessed December 24, 2025, https://2009-2017.state.gov/t/isn/5195.htm

- The SALT II Treaty. Part 2: hearings before the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, Ninety-sixth Congress, first session, on Ex. Y, 96-1 – Content Details – CHRG-96shrg48240Op2 – GovInfo, accessed December 24, 2025, https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/CHRG-96shrg48240Op2/CHRG-96shrg48240Op2

- The SALT II Treaty. Part 4: hearings before the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, Ninety-sixth Congress, first session, on Ex. Y, 96-1 – Content Details – CHRG-96shrg48260Op4 – GovInfo, accessed December 24, 2025, https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/CHRG-96shrg48260Op4/CHRG-96shrg48260Op4

- Israel–South Africa Agreement – Wikipedia, accessed December 24, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Israel%E2%80%93South_Africa_Agreement

- Revealed: how Israel offered to sell South Africa nuclear weapons – The Guardian, accessed December 24, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/may/23/israel-south-africa-nuclear-weapons

- The Vela Incident: South Atlantic Mystery Flash in September 1979 Raised Questions about Nuclear Test | National Security Archive, accessed December 24, 2025, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/nuclear-vault/2016-12-06/vela-incident-south-atlantic-mystery-flash-september-1979-raised-questions-about-nuclear-test

- The Discovery of South Africa’s Secret Nuclear Test Site, August 1977, accessed December 24, 2025, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/nuclear-vault/2023-10-26/discovery-south-africas-secret-nuclear-test-site-august-1977

- South Africa and weapons of mass destruction – Wikipedia, accessed December 24, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Africa_and_weapons_of_mass_destruction

- North Africa/Israel: Seth Carus and Dov Zakheim – Commission to Assess the Ballistic Missile Threat to the United States, accessed December 24, 2025, https://irp.fas.org/threat/missile/rumsfeld/pt1_africa.htm

- The 22 September 1979 Event – CIA, accessed December 24, 2025, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/DOC_0000037625.pdf

- The Vela Flash: Forty Years Ago | National Security Archive, accessed December 24, 2025, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/nuclear-vault/2019-09-22/vela-flash-forty-years-ago

- Revisiting the 1979 VELA Mystery: A Report on a Critical Oral History Conference, accessed December 24, 2025, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/revisiting-1979-vela-mystery-report-critical-oral-history-conference

- Once Top Secret images reveal evidence of above ground nuclear test, explosion, accessed December 24, 2025, https://ycitynews.com/26204/news/once-top-secret-images-reveal-evidence-of-above-ground-nuclear-test-explosion/

- Sent By: – . – 5 – 2 7 – 8 4 1 1: 4 6 Lanl-Nis-817037908724 2 – Scribd, accessed December 24, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/492267608/7738

- Navy Lab Concludes the Vela Saw a Bomb – Sci-Hub, accessed December 24, 2025, https://2024.sci-hub.se/4650/b83ccdd6467049e5601c72294e512e89/marshall1980.pdf

- Walking the Tightrope: Jimmy Carter’s Foreign Policy for a Nuclear Armed South Africa – UVIC, accessed December 24, 2025, https://www.uvic.ca/humanities/history/assets/docs/harry-davies—honours-thesis-2020—final.pdf

- Here’s How Radioactive Sheep Indicate That The Vela Incident Was A Secretive Nuclear Explosion | IFLScience, accessed December 24, 2025, https://www.iflscience.com/heres-how-radioactive-sheep-indicate-that-the-vela-incident-was-a-secretive-nuclear-explosion-49275

- The 22 September 1979 Vela Incident: The Detected Double-Flash – Science & Global Security, accessed December 24, 2025, https://scienceandglobalsecurity.org/archive/sgs25wright.pdf

- The 22 September 1979 Vela Incident: Radionuclide and Hydroacoustic Evidence for a Nuclear Explosion – Science & Global Security, accessed December 24, 2025, https://scienceandglobalsecurity.org/archive/sgs26degeer.pdf

- Online supplement The 22 September 1979 Vela Incident: Radionuclide and Hydroacoustic Evidence for a Nuclear Explosion Appendice – Science & Global Security, accessed December 24, 2025, https://scienceandglobalsecurity.org/archive/sgs26degeer_app.pdf

- Vela Incident | Military Wiki – Fandom, accessed December 24, 2025, https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/Vela_Incident

- NPR 1.1: A Chronology of South Africa’s Nuclear Program – James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, accessed December 24, 2025, https://www.nonproliferation.org/wp-content/uploads/npr/masiza11.pdf

- Jericho 2 | Missile Threat – CSIS, accessed December 24, 2025, https://missilethreat.csis.org/missile/jericho-2/