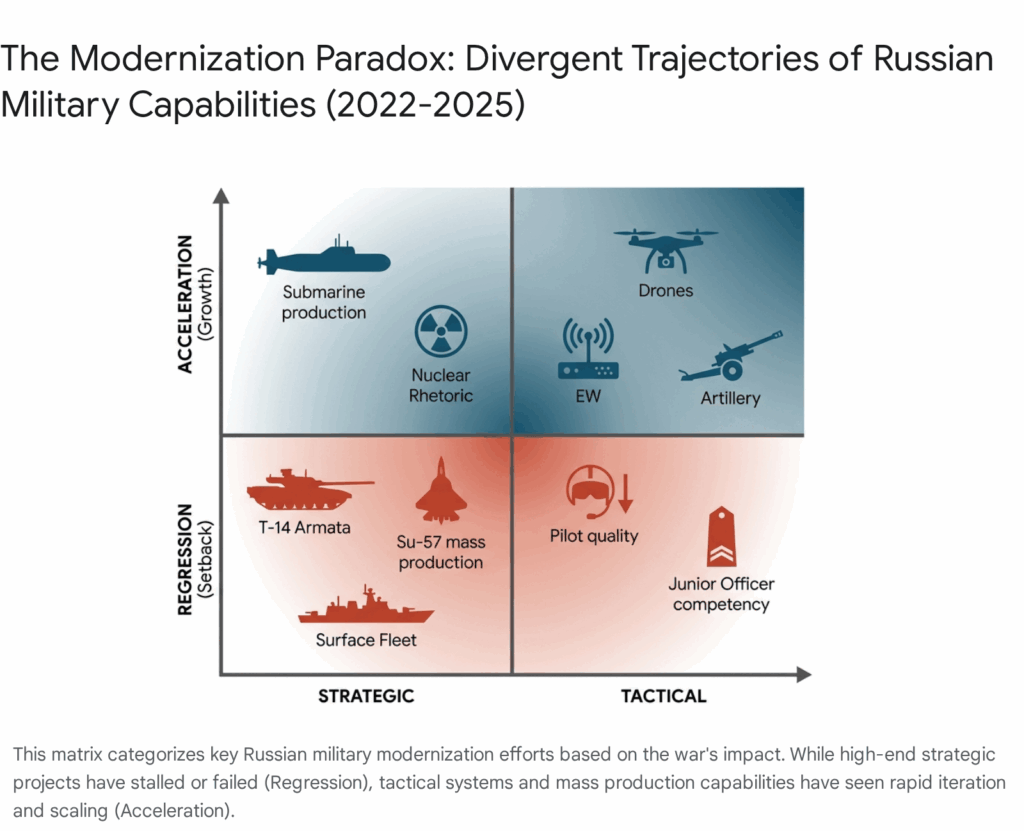

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, stands as a watershed moment in the history of the Russian Federation, serving as a brutal crucible for its armed forces and a definitive stress test for its decades-long military modernization efforts. Prior to this conflict, the Kremlin’s strategic vision—codified in the State Armament Programmes (GPV-2020 and GPV-2027)—was predicated on a transition from a Soviet-era mass mobilization army to a compact, professional, network-centric force capable of rapid expeditionary warfare and precision strikes. The war has violently derailed this linear trajectory, imposing a complex duality upon Russia’s military development: it acts simultaneously as a catastrophic strategic setback for high-end technological ambitions and a potent tactical accelerator for industrial scaling, combat adaptation, and the integration of autonomous systems.

This report, based on a comprehensive analysis of open-source intelligence, defense industrial data, and strategic doctrine, argues that the war has forced a “primitivization” of Russia’s strategic platforms while necessitating a “hyper-adaptation” in niche tactical domains. The aspiration for a high-tech “Armata” army has been shelved in favor of a mass-produced “T-90M and refurbished T-72” army. The result is not the modernized force envisioned in 2020, but a hybrid entity: larger, cruder, and heavily reliant on mass fires and attrition, yet increasingly lethal in its integration of cheap, expendable technologies like First-Person View (FPV) drones and glide bombs.

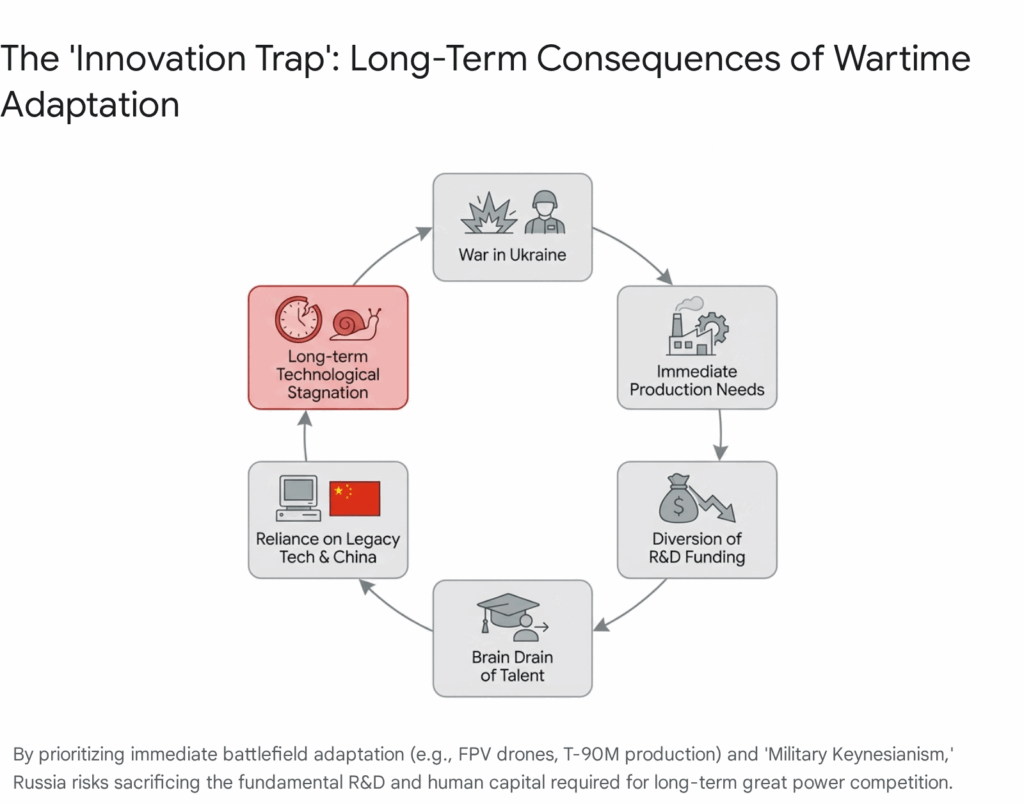

The analysis dissects this transformation across five key domains: Ground Forces and Armor, Aerospace and Missile Forces, Naval Operations, the Defense Industrial Base (DIB), and Strategic Weapons. It concludes that while Russia has successfully transitioned to a “military Keynesian” economy to sustain a long war, the structural degradation of its scientific-technical base, the severance from global high-tech supply chains, and the loss of human capital will severely constrain its ability to compete with NATO technologically in the post-2030 timeframe. Russia is trading its future modernization potential for immediate battlefield survivability, creating a force that is dangerous in its mass and resilience but increasingly obsolete in its underlying architecture.

1. The Pre-War Baseline: The “New Look” and the Promise of GPV-2027

To understand the magnitude of the shift caused by the war in Ukraine, one must first establish the baseline of Russia’s pre-war military trajectory. Following the perceived underperformance of the Russian Armed Forces during the 2008 Russo-Georgian War, the Kremlin initiated a sweeping series of reforms known as the “New Look.” Spearheaded by then-Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov and continued by his successor Sergei Shoigu, these reforms aimed to dismantle the skeletonized Soviet mobilization model—which relied on millions of reservists and vast stockpiles of equipment—and replace it with “permanent readiness units” staffed by professional contract soldiers (kontraktniki).1

1.1. The Ambitions of the State Armament Programmes

The financial engine of this modernization was the State Armament Programme (GPV). The GPV-2020, allocated 19.4 trillion rubles, succeeded in stabilizing the defense industry and updating the nuclear triad, but struggled to deliver next-generation conventional platforms.1 Its successor, GPV-2027 (2018–2027), was designed to be the “smart” phase of modernization. With a budget of approximately 20 trillion rubles ($330 billion), it prioritized precision-guided munitions (PGMs), autonomous systems, and the serial production of “breakthrough” platforms like the T-14 Armata tank and the Su-57 fighter.1

The strategic logic was clear: Russia acknowledged it could not match NATO in sheer expenditure or naval tonnage, so it sought asymmetric parity through superior missile technology (hypersonics), advanced air defense (A2/AD bubbles), and a highly mobile, networked ground force capable of winning short, decisive regional conflicts.

1.2. The Reality Check of 2022

The invasion of Ukraine exposed the hollowness of many of these assumptions. The “New Look” force, organized into Battalion Tactical Groups (BTGs), proved brittle in high-intensity combat. The reliance on sophisticated but few platforms (the “boutique army” concept) left Russia without the strategic depth to absorb losses. By 2025, the GPV-2027 goals have been largely rendered obsolete by the voracious demands of attrition warfare. The Kremlin has been forced to pivot from a modernization strategy based on quality to a survival strategy based on quantity and substitution.1

2. Ground Forces and Armor: The Death of the “Parade Army”

The Russian Ground Forces were the primary intended beneficiaries of the pre-war modernization drive. The vision was a force equipped with the Armata universal combat platform, a revolutionary family of vehicles sharing a common chassis, networked for data-centric warfare. The war has shattered this vision, replacing it with a grim industrial pragmatism.

2.1. The Failure of Next-Generation Platforms

By 2025, the T-14 Armata Main Battle Tank (MBT) remains virtually absent from the operational theater. Despite Rostec CEO Sergei Chemezov confirming the delivery of serially produced T-14s to the Ground Forces, he explicitly cast doubt on their deployment to Ukraine, citing their “exorbitant cost” and the need for funds to create cheaper, more disposable weapons.4

This admission is devastating for the narrative of Russian technological superiority. The T-14 was marketed as the world’s first “fourth-generation” tank, featuring an unmanned turret and an armored crew capsule. Its absence suggests two critical failures:

- Technological Maturity: The system likely suffers from unresolved reliability issues, particularly in its fire control and engine systems, which would be catastrophic in the mud and chaos of the Donbas.

- Risk Aversion: The Kremlin fears the reputational damage of a T-14 being destroyed or, worse, captured by Ukrainian forces and examined by Western intelligence.4

Consequently, the “modernization” of the tank fleet has shifted from innovation (fielding new chassis) to restoration (upgrading legacy hulls). The T-14 has effectively been relegated to the status of a “parade tank,” while the workhorse duties fall to older designs.

2.2. The T-90M “Proryv” and the Pivot to Mass

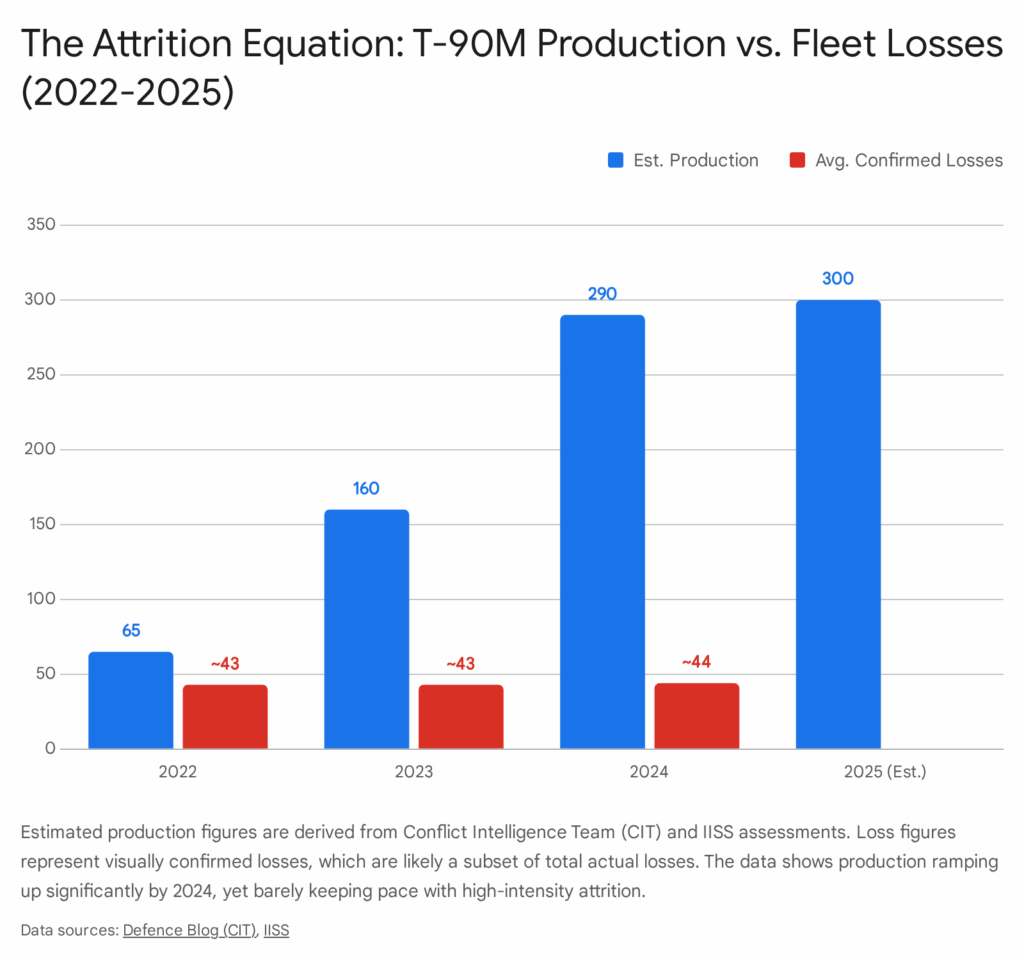

In the vacuum left by the T-14, the T-90M “Proryv” has emerged as the apex of Russian armored capability. Analysis of production rates indicates a significant, albeit insufficient, industrial surge. In 2022, Uralvagonzavod produced an estimated 60–70 T-90Ms. By 2024, utilizing 24-hour production cycles and expanded facilities, this figure had risen to approximately 280–300 units annually.6

This scaling represents a genuine industrial success for the Russian command economy. The T-90M is a formidable platform, featuring the Relikt explosive reactive armor (ERA), the 2A46M-5 gun, and improved thermal imaging. However, this “modernization” is relative. The T-90M is ultimately an evolution of the Soviet T-72 design, retaining the legacy autoloader and crew layout.

Furthermore, the attrition rates in Ukraine are staggering. Russia has lost over 3,000 tanks since February 2022, a number that exceeds its entire active pre-war fleet.7 While current production levels of T-90Ms and refurbished T-72B3s are sufficient to maintain fleet numbers for several more years 9, the quality of the fleet is bifurcating.

- The Elite Tier: A small percentage of units (VDV, Naval Infantry, Guards Tank Armies) are equipped with factory-fresh T-90Ms.

- The Mass Tier: The vast majority of mobilized units and assault detachments are equipped with older T-72s, T-62Ms, and even T-54/55s pulled from deep storage and minimally upgraded with thermal sights and “cope cages”.10

This dynamic signifies a technological regression. The average age of a tank in the Russian army in 2025 is significantly higher than it was in 2021. The reliance on refurbishment means that this “modernization” is cannibalistic; it depends on a finite stock of Soviet-era hulls that analysts estimate will be exhausted by 2026-2027.8

2.3. Degradation of Fighting Vehicles and Artillery

The situation is even more acute with Infantry Fighting Vehicles (IFVs) and artillery. The pre-war plan was to transition to the Kurganets-25 and Boomerang platforms. These programs, like the Armata, have stalled. Instead, the industry has struggled to produce even the late-Soviet BMP-3 and BMD-4 at rates that match battlefield losses.10

This production bottleneck has led to the widespread “de-modernization” of mechanized infantry. Units are increasingly deploying in BMP-1s (introduced in 1966) and MT-LBs (originally artillery tractors). The modernization efforts for these vehicles are purely functional improvisations—welding naval anti-aircraft guns (2M-3) or crude anti-drone screens onto the chassis.10 This represents a return to a mid-Cold War technological standard.

In the artillery domain—the “God of War” in Russian doctrine—the shift is from precision to volume. The loss of modern self-propelled guns (SPGs) like the 2S19 Msta-S has forced a reliance on towed artillery and older systems pulled from storage. However, the true accelerator in this domain is the integration of the kill chain. While the guns are getting older (and barrel wear is becoming a critical issue), the targeting cycle is becoming faster and more networked. The ubiquitous presence of commercial drones (Mavic 3) and military reconnaissance UAVs (Orlan-10/30) has shortened the time from target acquisition to fire mission from minutes to seconds.11 This paradox—older tubes, newer eyes—defines the current state of Russian fire support.

2.4. Tactical Evolution: The Rise of the “Storm” Detachment

The structural modernization of the Russian army has also been radically altered. The pre-war BTG structure, designed for maneuver warfare, proved too fragile. In its place, Russia has adopted the “assault detachment” (Storm-Z, Storm-V) structure.10 These are smaller, infantry-centric units designed for grinding urban combat and trench assaults. This is not the high-tech, network-centric warfare envisioned in 2020; it is a regression to World War I stormtrooper tactics, albeit enabled by drone reconnaissance. While this represents a setback in operational art, it is an effective adaptation to the reality of positional warfare against a deeply entrenched enemy.

3. Aerospace Forces: The Gap Between Stealth and Reality

The Russian Aerospace Forces (VKS) entered the war with a reputation as a near-peer competitor to the U.S. Air Force, bolstered by a decade of modernization and combat experience in Syria. The war in Ukraine has severely damaged this prestige, revealing critical limitations in training, doctrine, and the availability of precision-guided munitions (PGMs).

3.1. The Su-57 “Felon”: A No-Show in Contested Airspace

The Su-57 “Felon,” Russia’s fifth-generation stealth fighter, serves as a microcosm of the broader modernization failure. While Russian officials, including Rostec CEO Sergei Chemezov, claim the aircraft has “completed combat operations” and is being upgraded based on lessons learned 12, there is no verifiable evidence of it operating inside contested Ukrainian airspace. Instead, it appears to be used exclusively as a standoff launch platform from deep within Russian territory, firing long-range missiles like the R-37M or Kh-69.12

This cautious employment suggests a lack of confidence in the aircraft’s stealth characteristics or survivability against Western-supplied air defense systems (Patriot, NASAMS, IRIS-T). Furthermore, the reported damage to a Su-57 on the ground at Akhtubinsk airbase by a Ukrainian drone 15 underscores a humiliating infrastructure failure: Russia’s most advanced assets are safer in the air than they are on the ground, due to a failure to build hardened aircraft shelters (HAS)—a basic requirement that has been neglected in favor of procuring flashy platforms. The inability to protect the Su-57 fleet on the ground creates a strategic vulnerability that negates its theoretical airborne capabilities.

3.2. The “Glide Bomb” Adaptation: Technology of Necessity

If the Su-57 represents a modernization setback, the wide-scale adoption of UMPK (Unified Module for Planning and Correction) glide bombs represents a successful, albeit crude, adaptation.11 Realizing that its stock of expensive cruise missiles (Kalibr, Kh-101) was finite and that its aircraft could not safely operate over Ukraine due to dense air defenses, the VKS retrofitted “dumb” gravity bombs (FAB-500, FAB-1500, and even the massive FAB-3000) with cheap pop-out wing kits and GPS/GLONASS guidance.

This innovation has allowed the VKS to leverage its massive Soviet-era bomb stockpiles to deliver devastating strikes from stand-off ranges (50-70km), staying just outside the reach of most Ukrainian medium-range air defenses. This is an accelerator of capability, but one born of technological regression. It substitutes the precision of a purpose-built missile with the brute force of a heavy bomb, accepting lower accuracy for higher volume and significantly lower cost. It has fundamentally altered the frontline dynamics, allowing Russian tactical aviation to provide close air support without entering the engagement envelope of MANPADS.

3.3. Pilot Attrition and Training Degradation

A critical, often overlooked aspect of military modernization is human capital. The VKS has lost a significant number of experienced pilots, including senior officers who were forced to fly combat sorties due to a lack of qualified juniors.16 The training pipeline has been compressed to fill these gaps, leading to a long-term degradation in pilot quality.

The “modernization” of pilot training is now focused on the immediate needs of the “Special Military Operation” (SMO)—low-level flying, unguided rocket attacks, and glide bomb releases—rather than complex, large-force employment exercises (COMAO) required for peer conflict with NATO. This creates a generation of pilots who are combat-experienced but tactically limited. They are experts in the specific, constrained environment of the Ukraine war but are arguably less prepared for a multi-domain fight against a technologically superior air force.

4. The Unmanned Revolution: An Accelerator of Innovation

If traditional domains have seen regression, the field of unmanned systems has witnessed explosive acceleration. The war in Ukraine is widely recognized as the world’s first “drone war” 17, and Russia, after an initial lag where it relied on expensive and scarce Orlan-10s, has aggressively adapted its industrial and tactical approach.

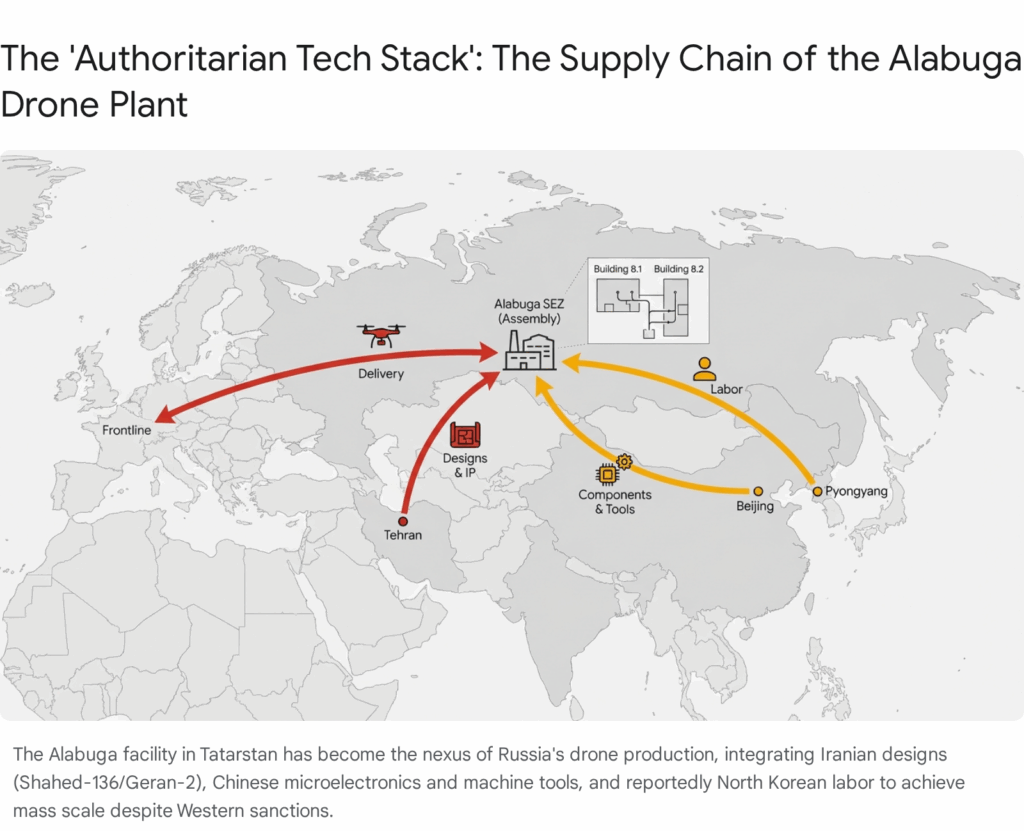

4.1. Industrialization of the “Shahed”: The Alabuga Complex

The establishment and expansion of the drone production facility in the Alabuga Special Economic Zone (Tatarstan) represents the most significant industrial achievement of the war. Originally assembling Iranian-supplied Shahed-136 (Geran-2) kits, Alabuga has transitioned to full-cycle domestic production. Satellite imagery and intelligence reports indicate plans to produce 6,000 units annually by 2025, a goal that appears to be ahead of schedule.18

This facility is a symbol of a new “Authoritarian Tech Stack,” where Russia integrates technologies and labor from its few remaining allies.

- Iran: Provided the base design (Shahed-136) and initial tooling.

- China: Supplies the microelectronics, carburetors, and CNC machine tools required for mass production.20

- North Korea: Intelligence reports suggest the planned deployment of North Korean labor to Alabuga to resolve chronic workforce shortages.22

This international collaboration has allowed Russia to bypass Western sanctions and achieve a scale of production for long-range strike assets that NATO countries are currently struggling to match.

4.2. FPV Drones and the “Sudoplatov” Model

At the tactical level, Russia has institutionalized the use of First-Person View (FPV) drones. The “Sudoplatov” volunteer battalion, which established a drone training and production school, exemplifies a shift from centralized, top-down procurement to decentralized, grassroots innovation.24 While initial iterations were criticized for poor quality and vulnerability to EW, the sheer volume of production—claimed to be thousands per day—has created a ubiquitous threat on the battlefield.25

This shift has forced a modernization of doctrine. The Russian military is creating specialized drone operators and units at the platoon level, a structural change that was not present in the 2021 order of battle. The “Rubicon” center for advanced drone technologies represents an attempt to centralize and standardize these grassroots innovations, integrating artificial intelligence for terminal guidance to overcome Ukrainian electronic warfare.11 This is a clear case of the war acting as an accelerator; without the conflict, the Russian military bureaucracy would likely have taken a decade to integrate FPV technology to this extent.

4.3. Electronic Warfare: The Invisible Modernization

Russia’s Electronic Warfare (EW) capabilities have also accelerated. Systems like the Pole-21 and Zhitel have been deployed in unprecedented density, creating “dead zones” for GPS-guided munitions and drones. The adaptation here is the shift from protecting high-value strategic assets to providing blanket coverage for trench lines. This constant cat-and-mouse game with Ukrainian drone operators has honed Russian EW operators into arguably the most combat-experienced in the world 27, a capability that poses a significant threat to NATO’s reliance on precision, networked warfare.

5. Naval Forces: A Tale of Two Fleets

The war has bifurcated the Russian Navy into two distinct realities: the beleaguered Black Sea Fleet, which has faced a modernization crisis, and the protected strategic submarine force, which continues to modernize largely largely unimpeded.

5.1. The Black Sea Fleet: A Strategic Defeat and Doctrinal Crisis

The Black Sea Fleet has suffered catastrophic losses, including its flagship, the Moskva, and roughly one-third of its combat power.28 Ukraine’s innovative use of Unmanned Surface Vessels (USVs) and coastal defense cruise missiles (Neptune, Harpoon) has forced the fleet to abandon its headquarters in Sevastopol and retreat to Novorossiysk.28

This defeat has forced a radical rethink of naval doctrine. The large surface combatants that were the pride of the fleet proved defenseless against cheap, asymmetric threats. The pre-war plans for large destroyers and carriers (Project 23000E Shtorm) now appear fantastical. The future of the Russian surface navy likely lies in smaller, corvette-sized vessels (Project 22800 Karakurt) equipped with long-range Kalibr or Zircon missiles, operating from the relative safety of coastal waters.30 The concept of “sea control” has been replaced by “sea denial” and fleet preservation.

5.2. The Submarine Force: Uninterrupted Modernization

Conversely, the submarine force—the cornerstone of Russia’s strategic deterrent—has continued its modernization largely unimpeded. The construction of Borei-A class ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) and Yasen-M class cruise missile submarines (SSGNs) continues at the Sevmash shipyards.30

The Yasen-M class, in particular, remains a potent threat to NATO, capable of launching the hypersonic Zircon missile.30 The divergence between the surface and subsurface fleets highlights a strategic prioritization: the Kremlin is willing to sacrifice “gunboat diplomacy” capabilities (surface ships) to preserve its “doomsday” capabilities (nuclear submarines). The war has effectively ended Russia’s ambition to be a blue-water surface naval power in the near term, focusing its resources instead on the undersea domain where it still holds a technological edge.

6. The Defense Industrial Base: The Shift to “Military Keynesianism”

The economic management of the war has been defined by the appointment of Andrey Belousov as Minister of Defense in May 2024, replacing Sergei Shoigu.32 Belousov, a technocratic economist, was brought in to optimize the defense budget and integrate the military needs with the broader economy—a strategy termed “Military Keynesianism”.33

6.1. Spending vs. Sustainability

Russia’s defense spending has skyrocketed to over 6% of GDP in 2025.3 This massive injection of state liquidity has stimulated GDP growth, but it has also created an overheating economy characterized by high inflation and acute labor shortages. The defense sector currently lacks an estimated 160,000 to 400,000 workers.34 To attract labor, defense plants offer inflated salaries, which cannibalizes the civilian sector and drives up wages nationwide, fueling a wage-price spiral that threatens long-term economic stability.33

6.2. The “China Pivot” and Technological Dependency

Perhaps the most critical structural change in the DIB is the shift from Western to Chinese industrial equipment. Prior to the war, Russia relied heavily on German, Japanese, and Italian precision machine tools for its defense industry. With Western sanctions blocking access to these goods, Russia has turned to China.

Analysis of trade data reveals a seismic shift in the provenance of Russia’s industrial machinery. In 2023-2024, Russia imported over $4 billion worth of CNC machines, with China accounting for the vast majority. Data from the Economic Security Council of Ukraine indicates that between January 2023 and July 2024, Chinese entities accounted for over 60% of CNC imports, effectively filling the void left by Western firms.20

While this has saved the Russian DIB from collapse, it creates a long-term vulnerability. Chinese machine tools are generally considered to be of lower precision and durability than their Western counterparts.20 Furthermore, this creates a total technological dependency on Beijing. Russia is no longer sovereign in its defense production; it is a downstream client of the Chinese industrial base. This dependency will likely constrain Russia’s ability to innovate independently in the coming decades.

7. Strategic Forces and Future Outlook: The Army of 2030

What will the Russian military look like after the war? The consensus among experts is that Russia will not return to the status quo ante. The “New Look” is dead; the “Future Look” is being forged in the Donbas.

7.1. Strategic Weapons: Between Bluster and Failure

Russia’s nuclear modernization has always been the “crown jewel” of its military strategy. However, the war has exposed cracks even here. The RS-28 Sarmat heavy ICBM, intended to replace the Soviet-era Voevoda (Satan), has suffered a series of humiliating failures. A test in September 2024 reportedly resulted in a catastrophic explosion that destroyed the launch silo at Plesetsk Cosmodrome, leaving a massive crater visible from space.38 This failure suggests deep systemic issues in the quality control and engineering sectors of the strategic rocket forces, likely exacerbated by the pressure to deliver results for political signaling.

Conversely, the Kremlin continues to double down on “exotic” nuclear-powered weapons like the Burevestnik cruise missile and Poseidon torpedo. In late 2025, President Putin announced successful tests of the Burevestnik.40 While these weapons are touted as “invincible,” their strategic utility is questionable, and their development consumes immense resources that could be used for conventional modernization. They serve primarily as tools of “nuclear blackmail” rather than practical military instruments.

7.2. The Innovation Trap

The most profound impact of the war is the creation of an “Innovation Trap.” By focusing all resources on immediate battlefield needs—mass-producing FPV drones, refurbishing T-72s, and casting iron bombs—Russia is starving its R&D sector of the resources needed for long-term breakthroughs.

The “brain drain” of young engineers and IT specialists, many of whom fled mobilization, further exacerbates this.34 Russia is adapting fast to the current war, but it is not innovating in the deep, structural sense required to compete with the US and China in the mid-21st century fields of AI, quantum computing, and next-gen stealth.42

Conclusion

Is the war in Ukraine a setback or an accelerator for Russia’s military modernization? The answer is a nuanced both, but the weight falls heavily on the side of strategic setback masked by tactical acceleration.

The war has accelerated:

- The integration of unmanned systems into every echelon of command.

- The industrial capacity to mass-produce “good enough” munitions and legacy platforms.

- The adaptation of electronic warfare and counter-drone tactics.

- The militarization of the economy and society.

The war has been a setback for:

- The development and fielding of next-generation platforms (Armata, Su-57, future naval combatants).

- The professionalization of the officer corps and the quality of human capital.

- The technological sovereignty of the defense industry (now dependent on China).

- The ability to project power globally, beyond Russia’s immediate periphery.

Ultimately, Russia is trading its future potential for present survivability. It is building a military that is dangerous, resilient, and capable of grinding out a victory in a regional war of attrition, but one that is increasingly ill-suited for a high-tech, global conflict against NATO. The “Modern Russian Army” envisioned in the 2010s died in the fields of Ukraine; in its place, a grimmer, cruder, but battle-hardened Leviathan is rising.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.

Sources Used

- Russia’s GPV-2027 State Arms Programme, accessed December 18, 2025, https://ridl.io/russias-gpv-2027-state-arms-programme/

- Russia’s State Armament Programme 2027: a more measured course on procurement, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.iiss.org/online-analysis/military-balance/2018/02/russia-2027/

- Russia’s struggle to modernize its military industry – Chatham House, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2025-07/2025-07-21-russia-struggle-modernize-military-industry-boulegue.pdf

- Chemezov Casts Doubt on T-14 Armata Deployment in Ukraine – Defense Security Monitor, accessed December 18, 2025, https://dsm.forecastinternational.com/2024/03/04/chemezov-casts-doubt-on-t-14-armata-deployment-in-ukraine/

- Ukrainian intelligence unveils details on Russian Armata tank production – Defence Blog, accessed December 18, 2025, https://defence-blog.com/ukrainian-intelligence-unveils-details-on-russian-armata-tank-production/

- Russia ramps up T-90M tank production – Defence Blog, accessed December 18, 2025, https://defence-blog.com/russia-ramps-up-t-90m-tank-production/

- The Russia-Ukraine War Report Card, Dec. 10, 2025, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.russiamatters.org/news/russia-ukraine-war-report-card/russia-ukraine-war-report-card-dec-10-2025

- russia’s T-90M and T-90M2 Tank Ambitions: Modernization, Overhauls, and Production Peaks Revealed | Defense Express, accessed December 18, 2025, https://en.defence-ua.com/industries/russias_t_90m_and_t_90m2_tank_ambitions_modernization_overhauls_and_production_peaks_revealed-16123.html

- How Many Т-90M Tanks does Russia Produce? CIT Research, accessed December 18, 2025, https://notes.citeam.org/eng_t90

- Historical Armor Losses: Shifting Tactics and Strategic Paralysis | Article – U.S. Army, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.army.mil/article/289399/historical_armor_losses_shifting_tactics_and_strategic_paralysis

- Seven Contemporary Insights on the State of the Ukraine War – CSIS, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/seven-contemporary-insights-state-ukraine-war

- Russia’s Su-57 Felon Stealth Fighter Is ‘In Action’ in Ukraine War – National Security Journal, accessed December 18, 2025, https://nationalsecurityjournal.org/russias-su-57-felon-stealth-fighter-is-in-action-in-ukraine-war/

- Su-57 With New Upgrade Options, Russia Claims First Foreign Delivery Has Already Occurred – The War Zone, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.twz.com/air/su-57-with-new-upgrade-options-russia-claims-first-foreign-delivery-has-already-occurred

- Sukhoi Su-57 – Wikipedia, accessed December 18, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sukhoi_Su-57

- Damaged Su-57 Emphasises the Vulnerability of Russian Airbases Near Ukraine – RUSI, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/damaged-su-57-emphasises-vulnerability-russian-airbases-near-ukraine

- Meeting Expectations: Failure in Ukraine Will Not Change the Russian Aerospace Defense Force, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/January-February-2025/Meeting-Expectations/Meeting-Expectations-UA.pdf

- Russia has learned from Ukraine and is now winning the drone war – Atlantic Council, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/russia-has-learned-from-ukraine-and-is-now-winning-the-drone-war/

- Imagery Update: New Construction Identified at the Alabuga Shahed 136 Production Facilities | ISIS Reports | Institute For Science And International Security, accessed December 18, 2025, https://isis-online.org/isis-reports/imagery-update-new-construction-identified-at-the-alabuga-shahed-136

- Russia doubles down on the Shahed – The International Institute for Strategic Studies, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.iiss.org/online-analysis/military-balance/2025/04/russia-doubles-down-on-the-shahed/

- Made in China 2025: Evaluating China’s Performance, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.uscc.gov/research/made-china-2025-evaluating-chinas-performance

- China-Russia Defense Cooperation Showcases Rising Axis of Aggressors – FDD, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.fdd.org/analysis/policy_briefs/2025/06/10/china-russia-defense-cooperation-showcases-rising-axis-of-aggressors/

- Adversary Entente Cooperation at Russia’s Shahed Factory Threatens Global Security, accessed December 18, 2025, https://understandingwar.org/research/adversary-entente/adversary-entente-cooperation-at-russias-shahed-factory-threatens-global-security/

- Alabuga: The Latest Destination for North Korea’s Drone Ambitions, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.38north.org/2025/12/alabuga-the-latest-destination-for-north-koreas-drone-ambitions/

- School for FPV drone operators – from manufacturing to combat use – RuAviation, accessed December 18, 2025, https://ruavia.su/school-for-fpv-drone-operators-from-manufacturing-to-combat-use/

- Head to Head: Ukraine and Russia’s National UAS Programs – Inside Unmanned Systems, accessed December 18, 2025, https://insideunmannedsystems.com/head-to-head-ukraine-and-russias-national-uas-programs/

- Russia’s Ministry of Defense is recruiting college students to join the army as drone operators – The Insider, accessed December 18, 2025, https://theins.ru/en/news/287699

- Lessons from the Ukraine Conflict: Modern Warfare in the Age of Autonomy, Information, and Resilience – CSIS, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/lessons-ukraine-conflict-modern-warfare-age-autonomy-information-and-resilience

- Russia’s Black Sea Failures Are Lessons for the South China Sea – U.S. Naval Institute, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2025/september/russias-black-sea-failures-are-lessons-south-china-sea

- Russia’s Black Sea defeats get flushed down Vladimir Putin’s memory hole, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/russias-black-sea-defeats-get-flushed-down-vladimir-putins-memory-hole/

- The Russian Navy’s Big Comeback Is Moving at ‘Mach 9 Speed’ – National Security Journal, accessed December 18, 2025, https://nationalsecurityjournal.org/the-russian-navys-big-comeback-is-moving-at-mach-9-speed/

- Russian Navy Expands with 22 New Vessels in 2025 – Caspianpost.com, accessed December 18, 2025, https://caspianpost.com/regions/russian-navy-expands-with-22-new-vessels-in-2025

- The Defense Industrial Implications of Putin’s Appointment of Andrey Belousov as Minister of Defense – CSIS, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/defense-industrial-implications-putins-appointment-andrey-belousov-minister-defense

- The Russian Wartime Economy, accessed December 18, 2025, https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2025-06/250605_Snegovaya_Wartime_Economy.pdf

- Russia’s struggle to modernize its military industry – Chatham House, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2025/07/russias-struggle-modernize-its-military-industry/identifying-weaknesses-russias-military

- Russia’s Year of Truth: The Runaway Military Budget – CEPA, accessed December 18, 2025, https://cepa.org/article/russias-year-of-truth-the-runaway-military-budget/

- Russian Defense Sector Increasingly Having Trouble Attracting Workers – Russia.Post, accessed December 18, 2025, https://russiapost.info/economy/defense_sector

- Russia imported over 22,000 foreign-made CNC machines & components in 2023-2024 despite intl. sanctions, new investigation shows – Business and Human Rights Centre, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/russia-imported-over-22000-foreign-made-cnc-machines-components-in-2023-2024-despite-intl-sanctions-new-investigation-shows/

- Russia’s new Sarmat missile suffered ‘catastrophic failure’: Researchers – Al Jazeera, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/9/24/russias-new-sarmat-missile-suffered-catastrophic-failure-researchers

- Prestigious Sarmat missile exploded in failed test – The Barents Observer, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.thebarentsobserver.com/security/prestigious-sarmat-missile-exploded-in-failed-test/166522

- Russia Tests Nuclear-Powered Cruise Missile, Torpedo – Arms Control Association, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2025-11/news-briefs/russia-tests-nuclear-powered-cruise-missile-torpedo

- Putin says Russia has begun development of new nuclear-powered cruise missiles, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/world/putin-says-russia-has-begun-development-of-new-nuclear-powered-cruise-missiles/3735293

- Russia and the Technological Race in an Era of Great Power Competition – CSIS, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/russia-and-technological-race-era-great-power-competition