From 1988 to 1989, I went to school in Kobe, Japan. On weekends I would wander through shopping areas and always looked carefully at the hardware, tool and knife vendor stores. Even then, big chopping blades would catch my eye and I found out they were known as “natas”. They were used much like a Western Hatchet intended for use by one hand to remove small limbs and split wood.

Before I returned home to the states, I picked up a 180cm basic model from a hardware store and it rattled around in my shop for years and years … I guess at this point I am old enough to say decades. The nata itself was very cool but over the years the vinyl covering stretched over a wood core slowly fell apart. Eventually, I decided to refinish the nata and sell it with a Kydex sheath.

The funny thing about time is that you can learn a lot along the way. You also get reminiscent about things in the past – in my case, I missed the nata. I’d gone head first down collecting and refurbishing cleavers, khukuris and and other blades – some of which I kept but I no longer had a nata and decided to correct that. Before we get into the three I bought, let’s look at the history of the nata design.

The History of the Japanese Nata

While the exact origin remains unclear, evidence suggests the nata’s presence as early as 720 AD. The word itself (鉈) appears in historical texts, but physical examples or depictions from that era are scarce. This lack of concrete evidence points to a likely origin deeply rooted in rural communities, where functionality overshadowed the need for artistic documentation.

Throughout Japan’s feudal period (794-1853), travel between regions was often challenging. This isolation fostered the development of regional variations of the nata, each tailored to the specific needs of its locality. Village blacksmiths refined the tool based on local materials and methods that evolved over time.

The Edo period (1603-1867) saw a rise in traveling woodcutters. This new mobility led to the spread of efficient nata designs. The “tomari-nata,” developed in Asahi Town, exemplifies this trend. Its unique, bird-beak-shaped tip facilitated stripping bark and collecting firewood, making it a favorite among woodcutters. The tomari’s popularity exemplifies how regional ingenuity could gain national recognition through practical advantages.

Today, several distinct nata styles persist, each reflecting its historical roots. Modern materials like carbon steel and alloy steel have replaced traditional iron, but the core function remains unchanged. Today, nata are prized for their lightweight design and exceptional edge retention, making them ideal for forestry and land management tasks.

Back to the Main Story

We happened to be visiting the Smokies and stopped by Smoky Mountain Knifeworks (SMKW). We visit about once a year and if you are in the Sevierville, TN, area, SMKW is a “must-visit” store with knives, firearms, tons of cooking stuff, antiques and more – click here for directions on Google Maps. I check out the latest in blades in their huge store room and my wife likes looking at all of the cooking and gift ideas downstairs.

At any rate, we were there when they were having an open house with tons of vendors and it just so happened that a representative of Condor Knife and Tool was there. I really like Condor and it’s been great watching them grow over the years. I told the fellow that I had a bunch of Condor blades and planned on buying two this visit.

Well, he and I talked for a few minutes and a really cool Nata-styled knife caught my eye. It is their “Batonata” designed by Joe Flowers and it’s a cool take on the nata design. One look and you know it’s a nata but with a slightly different shape to the head, burnt American Hickory handle and brass wire wrap to further secure the full tang in the handle.

The blade is 0.20″ thick 1075 high carbon steel. The blade itself is about 10″ and overall it’s just under 17.5″. The weight is just under 2 pounds.

I found the Batonata really easy to chop with. This surprised me due the the spine only being 0.20″ thick. The designer, Joe Flowers, compensated for this by giving the Batonata an oversize head thus having more mass up front. If you will recall force = mass x acceleration. The more mass there is then the more energy there is at the same speed of swing. The Batonata gets the extra mass by the raised steel above the axis of the spine. Going thicker to get more mass would also require more energy to cleve the wood out of the way – that’s why really thick blades make lousy machetes for example. Thicker blads tend to push the vines out of the way vs. slicing through them.

So, two thumbs up for the Batonata. Elegant design, well executed, cool sheath. It’s made in El Salvador instead of Japan but it never claimed to be a “Japanese” nata so we’ll let that part slide. Click here for it on Amazon and here are active listings on eBay:

A Traditional Nata – A Kakuri 210mm Nata

Kakuri is a corporation in Sanjo, Japan that was founded in 1946. They have designed and produced cutlery and woodworking and arborist tools for over 70 years and fully understand what a nata is. By the way, click here to open a new tab showing all of the cool woodworking and gardening tools Kakuri has for sale on Amazon.

The nata I chose was a basic “Gikoh” series 210mm (8.27″) nata. With a nata, the length given in mm is the length of the blade. It’s also 405mm (15.94″) overall. The nata itself weighs approximately 1.3 pounds.

Most nata makers will have some high-end offerings with better wood, finishes and sheaths in addition to the basic work models with no frills. Kakuri is the same – though they only have one higher-end model and most are working class tools.

One thing I find interesting is their use of high carbon Japanese Yasuki steel. Yasuki (also sometimes written as Yasugi) is a family of steels used in a variety of cutting tools. Yasuki has a very long history dating back to sword making but now owned and produced by Hitachi Metals.

The handle is made from oak wood and has a clear coat finish on it.

I found the Kakuri nata very easy to swing and it took a good bite out of some old oak I had lying around during testing. The edge held up very nicely despite hitting the dried oak.

The score – two thumbs up for a well executed classic nata. Click here to open a new tab with the various Kakuri Nata listings on Amazon and here are active listings on eBay:

So far, you have seen a nata-inspired design in the Batonata. A classic design from Kakuri and now we need a modernized design from Japan.

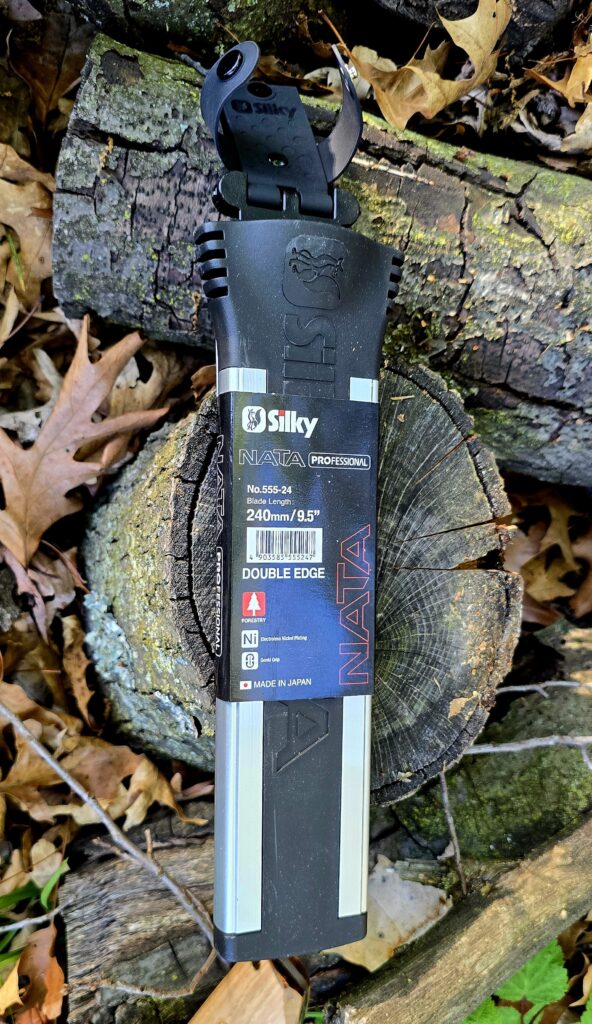

The Silky 240mm Double-Edge Nata

When I was searching for a new nata, I really did not expect to run into this modernized nata from Silky. The blade looks like a nata but everything else is modernized – rubber shock absorbing handle (a BIG thank you for those of us with carpal tunnel) and futuristic looking shealth made from aluminum and polymers.

“Who is Silky?” was my very first thought. The name alone did not sound Japanese but that could just be a brand name or something for the export market so I had to look them up.

Silky is the brand name for U.M. Kogyo located in Ono, Hyogo prefecture, Japan. The company was originally named “Tamakitsune” and was founded in 1919 by Mr. Katsuji Miyawaki to make saws. Today, Silky is led by Uichi Miyawaki who continues to stress excellence.

To be sure, their focus is on saws for woodworking and arborists plus they make a few innovating nata models. Their distributor in the US is Vertical Supply Group and they sell the saws on Amazon [click here to open a listing in a new tab].

This nata has a 240mm (9.44″) blade that is 5.7mm (0.22 inches) thick and has an overall length of 340mm (13.35″). The weight is 2.11 pounds.

They say an “alloy steel” is used but don’t get into the details. I did some digging and it is reported as a SKS-51 (JIS) steel. SKS-51 is a cutting tool steel that is tough with good wear resistance. It also has a full length tang that extends almost the full length of the handle but is hidden from sight.

There are three interesting design points that I want to share. First is the “Genki” (that usually translates as health or healthy) rubberized grip. It absorbs the shock instead of your hands – I totally agree on this point. It was the most comfortable nata for me to use. It’s also replaceable without tools.

The second point is the blade finish – it’s an electroless nickel plate that both reduces friction and corrosion. They developed it for their saws to more consistently reduce friction.

The third, is that the nata is user-maintainable. Their suppliers carry replacement handles, blades and quick release clips for the sheath.

Another two thumbs up. It’s an innovative design and the most comfortable for me to chop with – especially given my carpal tunnel.

You can find Silky Natas on Amazon sometimes (I bought mine there) – so click here to see them. Also, the following active listings are on eBay:

Comparing the Three Natas

It’s not easy to compare them and have a clear winner that everybody will agree with. It comes down to preferences. I’m going to first show you some comparison photos and then tell you my order of preference and why.

So, my ranking is:

#1 – The Silky Nata – the rubber hande absorbs a ton of the shock and the thing is a chopper and a half. I will definitely use it more when I need something like a hatchet. It will have to compete with my khukuris but none of them have the extremely comfortable Genki handle.

#2 – The Batonata – The handle is comfortable and it takes a good bite. I definitely like the sheath. It looks cool too. Kudos to Condor for turning out a really decent nata-inspired blade.

#3 – The Kakuri – I have carpal tunnel and a handle of that size and shape is hard on my hands when I chop. It’s a perfectly decent nata and not the fault of the designers but I don’t see myself using it much going forward. If someone wants a traditional basic nata, I’d have no reservation recommending it.

Summary

I hope this gave you some history on the natas plus three models to think about. I’m definitely going to continue using the Silky and probably the Batonata but the Kakuri would be problematic with my carpal tunnel.

I truly hope this helps you out.

Note, I have to buy all of my parts – nothing here was paid for by sponsors, etc. I do make a small amount if you click on an ad and buy something but that is it. You’re getting my real opinion on stuff.

If you find this post useful, please share the link on Facebook, with your friends, etc. Your support is much appreciated and if you have any feedback, please email me at in**@*********ps.com. Please note that for links to other websites, we are only paid if there is an affiliate program such as Avantlink, Impact, Amazon and eBay and only if you purchase something. If you’d like to directly contribute towards our continued reporting, please visit our funding page.